Foreword

We are pleased to present this first collection of publications under the Japan-Australia Dialogue and Exchange (JADE) for the Next Generation initiative, a collaboration between the United States Studies Centre and The Japan Foundation.

This publication arrives at an important moment for the bilateral relationship, for deepening Australia-Japan strategic cooperation has become an increasingly important pursuit for both countries. Beginning with the 2007 Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation (JDSC) and reflected in the elevation of the relationship to a Special Strategic Partnership in 2014 and the issuing of an updated JDSC in 2022, the two countries have taken their relationship from strength to strength. Such has been the success of these efforts that Australia and Japan now regard one another as their most important strategic partner after the United States.

Yet sustaining that momentum over the long term will require building a deeper mutual understanding between the political and strategic communities in both countries. The success of those efforts will rest largely on strengthening people-to-people ties, and particularly building lasting connections between emerging Australian and Japanese thought leaders who will carry the relationship forward in the coming decades. However, compared with the breadth of scholarship and depth of connections between the policy and intellectual communities in the US-Japan and US-Australia alliances, respectively, those that undergird the Special Strategic Partnership between Australia and Japan are comparatively underdeveloped. Building out this knowledge foundation will be essential for the bilateral relationship to live up to the ever-expanding role that both countries see for it in their national strategies.

If the exemplary work of this initial cohort of JADE Fellows is anything to go by, then the future of the Australia-Japan strategic partnership is in great hands.

It is in that spirit that the USSC and the Japan Foundation established the JADE Program in 2024. This initiative seeks to strengthen the intellectual infrastructure undergirding the Australia-Japan relationship, and to bridge the gap between the two countries’ strategic policy communities and their robust cultural, business and area studies communities. It does so through connecting and empowering emerging academic, industry and policy talent from both countries, positioning them to make meaningful contributions to an increasingly intimate partnership between two of the Indo-Pacific’s most influential and important democratic powers.

This first collection of JADE Fellow publications — focused on issues relating to maritime security in the Indo-Pacific — is more than a simple reflection of the successful outcomes of the initiative’s first year. It is a testament both to the policy talent of a new cohort of thought leaders from across the academic, business and government communities in Australia and Japan, and to the deep and enduring interest that the next generation has in strengthening the intellectual foundations of this important bilateral relationship.

If the exemplary work of this initial cohort of JADE Fellows is anything to go by, then the future of the Australia-Japan strategic partnership is in great hands. The United States Studies Centre looks forward to continuing to work with the Japan Foundation and future JADE cohorts in support of that important mission.

Dr Michael J. Green

Chief Executive Officer, United States Studies Centre

Dr Peter J. Dean

Director, Foreign Policy and Defence, United States Studies Centre

Closing the gap: Envisioning greater bilateral coordination between Japan and Australia in response to escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula

Jack Butcher

PhD Candidate, the University of Adelaide

Jack Butcher is a PhD Candidate and Adjunct Lecturer of International Security at the Department of Politics and International Relations at Adelaide University. His research focuses on the role of security practices, such as alliances, strategic partnerships, minilateralism, multilateralism and security communities, on the construction of order in East Asia. His other research interests include the historical and contemporary international relations of East Asia, as well as Japan-Australia and China-Australia relations. Jack recently published in the Australian Journal of International Affairs, the Lowy Interpreter, and was interviewed by Nikkei Asia on China-Vietnam relations.

Executive summary

- The security situation on the Korean Peninsula has deteriorated significantly over the past year with North Korea’s signing of a ‘Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’ with Russia, the deployment of North Korean troops to Ukraine and Pyongyang’s increasingly aggressive posture towards South Korea.1

- Japan and Australia have been watching the escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula with growing concern, given their shared interest in curbing North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

- However, Tokyo and Canberra still hold different views as to where the Korean Peninsula sits on a list of strategic priorities due to geographical differences and resource constraints.

- These mismatching priorities could adversely affect the deepening security relationship between Japan and Australia and trilateral planning with the United States, especially if conflict was to erupt on the Korean Peninsula with other flashpoints in the Indo-Pacific, such as the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea.

- This report aims to explore and envision how Australia could coordinate more closely with Japan in response to the escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula while still recognising the geographical and resource limitations that impact Canberra’s overall ability to contribute.

Key policy recommendations

- Japan and Australia should consider the possibility that the Trump administration will engage North Korea in dialogue over its nuclear weapons program, and if it does, jointly coordinate on how to pre-emptively shape the United States’ approach towards negotiations.

- Japan and Australia should aim to build their resilience against North Korean cyber-attacks and supply chain disruptions in the short term by:

- Lending Japan Australia’s expertise in cybersecurity by declaring a ‘cyber partnership’ that aims to align Tokyo’s cybersecurity policy frameworks with Five Eyes standards.

- Institutionalising a Track 1 trilateral dialogue with South Korea to consult, exchange information and design joint responses to potential supply chain disruptions linked to North Korean ballistic missile tests, cyber-attacks and incidents at sea.

- In the longer term, Japan and Australia should aim to strengthen joint planning for a future Korean contingency to deter and respond to, if necessary, a hypothetical North Korean attack on South Korean and US forces stationed on the Korean Peninsula and in Japan by:

- Commencing discussions about potential rotations of Australian Defence Force (ADF) assets and personnel through Japan Self-Defense Force (JSDF) facilities in Japan, as well as those designated by the United Nations Command-Rear in the event of a contingency.

- Deepening consultations about integrating command and control between the JSDF and the ADF to effectively plan, coordinate and control joint forces and operations.

- Widening the scope of naval and air exercises, as well as operational intelligence sharing, between the JSDF and the ADF to enhance the degree of interoperability required for combat support missions on and around the Korean Peninsula in the event of a worst-case scenario.

- Ensuring Australia’s rapid inclusion into the United States and Japan’s Integrated Air Missile Defence (IAMD) architecture by offering the JSDF the use of Australian missile testing ranges to facilitate deeper integration of Japan and Australia’s missile capabilities and industrial defence bases.

This report aims to explore and envision how Australia could coordinate more closely with Japan in response to the escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula while still recognising the geographical and resource limitations that impact Canberra’s overall ability to contribute.

Introduction: Australia, Japan, and escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula

The security situation on the Korean Peninsula has been progressively worsening since the 2019 Hanoi Summit, which failed to produce a diplomatic outcome towards North Korea’s complete denuclearisation.2 However, the situation has deteriorated more significantly over the past year due to recent shifts in Pyongyang’s policies and posture.3 The first shift was to its broader foreign and defence policy, which saw the signing of a ‘Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’ with Russia and the deployment of 11,000 Korean People’s Army (KPA) personnel to the Russo-Ukrainian War.4 The second was regarding its posture towards South Korea. In January 2024, Pyongyang categorically ‘ruled out’ reunification with Seoul, which led to the abandonment of five decades of official policy, and in November, issued an alarming order calling for ‘full war preparations’ against South Korea that even included the use of nuclear weapons.5

Although conflict does not appear imminent as of early 2025, the United States and its allies have still been watching escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula with growing concern.6 Two of Washington’s closest allies, Japan and Australia, have also been deepening their defence relationship partly in response to the worsening security situation on the Korean Peninsula.7 In October 2022, Tokyo and Canberra signed an updated version of the ‘Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation’ (JDSC), which includes an alliance-like clause committing both sides to consult on contingencies that affect their sovereignty and regional interests and to consider countermeasures.8 The JDSC followed the landmark signing of the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) in January 2022 as Japan’s first defence treaty with an international partner since the 1960 Anpo jōyaku ‘US-Japan Security Treaty’.9 While not a formal alliance, the RAA will streamline the deployment of their respective militaries to each other’s territories, enabling more sophisticated security cooperation.10

Despite the escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula having some influence on their deepening alignment, Japan and Australia still hold different views as to where the issue sits on a list of strategic priorities. For Tokyo, the Korean Peninsula is a core concern given its geographical proximity. Meanwhile, for Australia, it is viewed as an issue of lesser strategic importance due to its geographical distance from the Korean Peninsula and the proximity of other flashpoints to the Australian mainland, such as Taiwan and the South China Sea. While a more limited strategic focus is understandable given Canberra’s difficulty in projecting power into Northeast Asia, the mismatch in strategic priorities could have adverse effects on Australia’s deepening security relationship with Japan, particularly if conflicts were to erupt in quick succession on the Korean Peninsula and in the Taiwan Strait.11 For example, a recent crisis simulation found that the mismatch has the potential to spark disagreements over risk tolerances and resource allocation in a trilateral response with the United States, should both flashpoints erupt simultaneously.12

Therefore, recognising the problem that this mismatch poses while also considering the real limits that Australia has in shaping developments on the Korean Peninsula, this report aims to explore how Canberra could coordinate more closely with Tokyo in response to the heightened tensions. Firstly, this report highlights the significance of Japan and Australia to each other on the Korean Peninsula by examining where their interests intersect. Second, the report outlines recent cooperation between the two vis-à-vis the Korean Peninsula, which has occurred largely within the scope of their respective alliances with the United States. Third, the report explores the potential for deeper bilateral coordination between Tokyo and Canberra on the Korean Peninsula by envisioning it in three areas: pre-emptively shaping the United States’s approach to hypothetical negotiations with North Korea, building resilience against provocations from Pyongyang in the short-term, and planning for contingencies on the Korean Peninsula to deter North Korea over the long term. The report then concludes by offering a set of policy recommendations to facilitate deeper coordination vis-a-vis the Korean Peninsula.

The relevance of Japan and Australia to each other on the Korean Peninsula

Japan and Australia each view North Korea’s expanding nuclear weapons program as gravely concerning and have leveraged their military and diplomatic influence in an attempt to curb its expansion.13 However, as of 2025, Pyongyang has still developed enough nuclear fissile material to produce 90 nuclear warheads and assembled 50 nuclear weapons for deployment on both land and sea.14 North Korea’s ongoing refinement of its nuclear weapons program poses an existential threat to Japan due to the potential for a ballistic missile to hit Japanese territory and the negative precedent it sets for nuclear proliferation in East Asia.15 In October 2022, Pyongyang test-fired the intermediate-range ballistic missile Hwasong-12 over the Tohoku region on the main island of Honshu, into the North Pacific Ocean. In response, the Kishida cabinet issued an emergency warning for its citizens to seek shelter and strongly rebuked North Korea.16 The October 2022 incident followed a similar test during the height of the 2017-2018 Korean Peninsula Crisis and other tests that have landed in Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).17

Despite being evident to Japan due to its geographical proximity to the Korean Peninsula, the threat from Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons program seems less apparent to Australia but, in reality, is still as dangerous. Recent advances in its nuclear capabilities mean that the entire Australian continent now falls within the range of North Korea’s longest-range Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) Hwasong-15.18 Although Pyongyang has threatened Australia with a nuclear strike in the past, Canberra’s external commitments, such as its contribution to the United Nations (UN) Joint Command in Korea and its alliance with the through the Australia-New Zealand-United States (ANZUS) Treaty, are more likely to draw Canberra into a hypothetical Korean conflict than any direct strike.19 Australia has not backed down from defending its ally in the face of North Korean ballistic missile threats either. In 2017, then-Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull threatened to invoke the ANZUS Treaty against Pyongyang if it followed through on its threat to strike US forces in Guam.20

Therefore, given the multidimensional threat that North Korea’s nuclear weapons program poses, Japan and Australia have vocally supported a tightened UN sanctions regime and contributed to their enforcement in maritime waters near the Korean Peninsula.21 Since Pyongyang’s first nuclear test in 2006, Tokyo and Canberra have complied with UN Security Council resolutions to restrict North Korea’s ability to obtain funding, technology, and raw materials from external sources to further develop its nuclear weapons program. These include bans on money transfers, exports of gold, rare-earth minerals, copper, zinc, and natural gas to Pyongyang, as well as limitations on coal exports and oil imports.22 Meanwhile, to enforce sanctions, Australia and Japan have supported international efforts through Operation Argos. This has seen Canberra play a central role in monitoring and deterring ship-to-ship transfers in the Yellow Sea, with the JSDF supplying the ADF with crucial naval intelligence.23

In addition to curbing North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, Japan and Australia have a strong interest in preventing supply chain disruptions on and around the Korean Peninsula. If a hypothetical crisis were to erupt that escalated into a second Korean conflict, the potential disruptions to international trade would result in massive economic losses for Canberra and Tokyo. As insular maritime states located off the coast of continental Northeast and Southeast Asia, Japan and Australia are highly reliant upon international Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOCs) for the import and export of goods and natural resources. One of these core SLOCs for energy resources notably traverses the south of the Korean Peninsula through the Tsushima Strait and flows into the East China Sea and the Sea of Japan, which would likely be affected in the event of a conflict.24

Alongside neighbouring SLOCs, South Korea’s national security is directly tied to Japan’s and Australia’s economic security due to their profound degree of trade and resource interdependence. In 2024, South Korea became Japan and Australia’s third-largest two-way trading partner valued at US$71.1 billion and US$39 billion, respectively. For Japan, the three largest exports to South Korea consist of Machinery Having Industrial Functions ($5.4 billion), Integrated Circuits ($4.1 billion), and Refined Petroleum ($2.3 billion), and its three top imports from Seoul are Refined Petroleum ($5.3 billion), Integrated Circuits ($1.6 billion) and Hot-Rolled Iron ($921 million).25 The economic relationship between the two countries was affected from 2019 to 2023 by a trade war stemming from historical grievances.26 However, this has stabilised since the now-impeached President of South Korea, Yoon Seok-yeol, assumed office in 2022.27

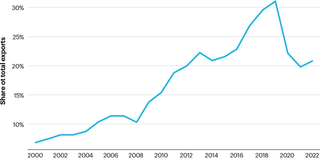

Australia’s greater dependency on exports to and imports from South Korea could lead to even more profound disruptions to its economy than Japan in the event of a Korean contingency. Canberra is a major supplier of raw materials and agricultural products to Seoul. Australia’s top three exports to South Korea are coal ($6.9 billion), liquefied natural gas (LNG) ($6.1 billion), and iron ore ($4.9 billion).28 If Japan becomes entangled in a contingency, the economic costs for Australia could be even higher. Tokyo accounts for 17.9% of Canberra’s total exports and 36% of its total LNG exports. When combined with LNG exports to South Korea (14%), a Korean contingency could result in roughly 50% of Australia’s LNG exports ($92 billion) being affected, which would cause significant damage to an economy already heavily dependent on the export of natural resources.29

In order to exert pressure on North Korea to limit the expansion of its nuclear weapons program and prevent it from acting provocatively towards South Korea, deepening security cooperation between the United States, South Korea, Japan and Australia has become vital in maintaining a favourable strategic balance on the Korean Peninsula.

Therefore, in order to exert pressure on North Korea to limit the expansion of its nuclear weapons program and prevent it from acting provocatively towards South Korea, deepening security cooperation between the United States, South Korea, Japan and Australia has become vital in maintaining a favourable strategic balance on the Korean Peninsula. However, the recent signing of the North Korea-Russia CSP and the ‘no limits’ strategic partnership between China and Russia have the potential to alter this balance.30 Pyongyang’s recent unveiling of suicide attack drones and a nuclear-powered submarine capable of carrying ballistic missiles suggests that a shift may already be underway.31 Alongside the long-standing but historically complex China-North Korea alliance, the power dynamics on the Korean Peninsula are now increasingly reminiscent of the Cold War, where Pyongyang effectively pivoted between Moscow and Beijing for economic and military aid to help sustain its resource-poor economy.

The reversion of Cold War era-type alignments means that it will be increasingly difficult for the United States and its allies to exert a maximum pressure policy of sanctions on North Korea as it decreases incentives for Pyongyang to change its behaviour and may even embolden it to act more aggressively. Due to the adversarial relations between the United States and its allies on the one hand and China and Russia on the other, Beijing and Moscow could be less willing to apply pressure on North Korea and may even aim to disrupt Australian and Japanese efforts to enforce sanctions. Indeed, this potential was most recently demonstrated when the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) directed sonar pulses towards Royal Australian Navy (RAN) divers on HMAS Toowoomba within Japan’s EEZ in late 2023, as they participated in Operation Argos to enforce sanctions against North Korea.32

Recent coordination between Japan and Australia vis-a-vis the Korean Peninsula

Although China’s naval expansion has been the primary factor driving security cooperation between Japan and Australia in the Western Pacific, many of the recent initiatives aimed at Beijing also have flow-on effects for managing rising tensions on the Korean Peninsula. One of these initiatives has been the increased sharing of intelligence between Tokyo, Canberra and Washington. In November 2023, a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) P-8 Poseidon joined the Japan Air Self-Defense Forces (JASDF) and the United States Navy (USN) in joint intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) in the maritime waters surrounding Japan.33 Australia’s participation in trilateral ISR complements plans for Canberra’s inclusion into the “Japan-U.S. Bilateral Information Analysis Cell” (BIAC), which will likely enhance its ability to interdict ships bound for North Korea by providing the ADF access to real-time intelligence.34

In addition to greater intelligence sharing, Australia and Japan have hosted bilateral military exercises to support US and South Korean efforts to deter North Korean provocations. Since the deterioration of relations with China, Australia has shown an increased willingness to participate in military exercises with Japan. Although primarily designed to deter Chinese maritime coercion, joint exercises have also been directed towards addressing escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula with a focus on maintaining regional peace and stability.35 Aside from the naval Exercise Nichi-gou Trident, which was first commissioned in 2009, Tokyo and Canberra held Exercise Bushido Guardian in September 2023 for the first time since the RAA came into effect.36 This saw the RAAF deploy six F-35 Lightning II fighters to Komatsu Air Base in Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan, for joint combat training over a nine-day period. The RAAF’s participation in Bushido Guardian 23 was notably preceded by two Japan Air Self-Defence Forces (JASDF) F-35s visiting RAAF Base Tindal in Australia’s Northern Territory on their first overseas deployment in August 2023.37

Trilateral exercises with the United States have been the largest area of growth, though. In 2023, more than 200 ADF personnel participated alongside 1,500 US Army personnel and 4,500 personnel from the Japan Ground Self-Defense Forces (JGSDF) in the largest iteration of Exercise Yama Sakura.38 Yama Sakura helped to increase interoperability between Australian, Japanese and US ground forces to respond to potential conflict scenarios across the Indo-Pacific, including on the Korean Peninsula.39 In addition to participating in Yama Sakura for the second time in 2024, Australia also joined Exercise Keen Edge and Exercise Keen Sword alongside the United States and Japan. Exercise Keen Sword saw 80 ADF personnel deployed to work with the US Armed Forces (USAF) and the JSDF to simulate the defence of Japan. Canberra is expected to participate in Exercise Orient Shield for the first time in 2025 — the largest land-based exercise between US and Japanese forces to enhance readiness for potential contingencies.40

Plans to create a “networked air defense architecture” between Washington, Tokyo and Canberra were announced at the US-Japan Summit Meeting in April 2024. Although China’s growing edge in conventional and nuclear strike capabilities played a large role in its declaration, integrating the three nations’ missile defence helps deter and potentially respond to North Korean missile threats.

Japan and Australia have also made plans to integrate their military-industrial bases with the United States and among each other as tensions on the Korean Peninsula and in other regional flashpoints rise. At the US-Japan Summit Meeting in April 2024, former US President Joe Biden and then-Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio announced plans to create a “networked air defense architecture” between Washington, Tokyo and Canberra.41 Although China’s growing edge in conventional and nuclear strike capabilities played a large role in its declaration, integrating the three nations’ missile defence helps deter and potentially respond to North Korean missile threats. In March 2024, the Pacific IAMD Center (PIC) conducted the Multilateral IAMD eXperiment (MIX) that brought together IAMD professionals from the United States, Japan and Australia. The experiment saw planners design geographically based command and control (C2) systems across the Pacific to respond to hypothetical provocations from Pyongyang.42

Integrating missile defence serves as a smaller snapshot of a broader agenda of defence technology cooperation driving Japan and Australia’s deepening strategic alignment.43 Given Pyongyang’s unveiling of a nuclear-powered submarine, cooperation on research and development (R&D) of maritime defence technology could not be more timely.44 In January 2024, Japan’s Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Agency (ATLA) signed an agreement for research on undersea warfare with Australia’s Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG). The agreement will see Tokyo and Canberra cooperate on achieving underwater acoustic communication technology for collaboration between Underwater Unmanned Vehicles (UUV).45 If successful, the project will enable greater detection of and response to threats posed to Japan’s security by North Korea’s growing capability to conduct undersea warfare.

Meanwhile, a series of bilateral, trilateral and minilateral dialogues have facilitated their joint agenda to strengthen sanctions enforcement, military exercises and military-industrial integration. The “2+2” Foreign and Defence Ministerial Consultations between Japan and Australia have served as the premier bilateral forum since 2008 to jointly condemn North Korean missile launches and discuss responses.46 In its 11th iteration in 2024, both sides reaffirmed their cooperation in dealing with Pyongyang and its advancements in military cooperation with Russia.47 The Trilateral Strategic Dialogue (TSD) with the United States has also assisted in the formulation of joint approaches towards the Korean Peninsula. The Joint Statement of the Trilateral Defense Ministers’ Meeting (TDMM) in 2024 strongly condemned North Korea’s military cooperation with Russia and committed to expanding joint exercises, operational coordination, planning and demonstrating a greater regional presence.48

Japan and Australia have also approached South Korea to explore trilateralism to help manage tensions on the Korean Peninsula. In July 2024, Canberra, Tokyo and Seoul held their first Track 1-level leaders’ dialogue, where they strongly condemned the “illicit military cooperation between the Russian Federation and North Korea” and called upon both countries to “immediately cease all activities that violate UNSC resolutions.”49 In November 2024, representatives from the three countries also convened a Track 1.5 dialogue for ‘future-oriented cooperation’.50 The participants emphasised the importance of aligning strategic planning among Japan, Australia and South Korea, and building sufficient capacity to respond in the event of a Korean contingency or if several flashpoints erupt rapidly across the Indo-Pacific.51

Envisioning greater coordination in response to escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula

Despite recent policies having flow-on effects for managing escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula, Japan and Australia should do more in a bilateral capacity to ensure that their security relationship is not adversely affected by their mismatched priorities in the Western Pacific.52 Deepening bilateral coordination with the aim of complementing US and South Korean efforts to manage tensions on the Korean Peninsula will be even more crucial now that President Donald Trump has returned to the White House. Therefore, Tokyo and Canberra will need to envision ways to coordinate more independently of the United States while also trying to moderate some of the President’s more revisionist and transactional preferences. Although Australia’s degree of involvement on the Korean Peninsula will be constrained by geographical factors and power limitations, there are ways that Canberra can still help Tokyo respond to new developments. These include pre-emptively shaping the United States’ approach to negotiations with North Korea, building resilience against provocations from Pyongyang in the short term, and planning for hypothetical contingencies to deter North Korea in the long term.

Pre-emptively shaping Trump’s approach to negotiations with North Korea

Japan and Australia will need to consider the possibility that the Trump administration may engage North Korea in dialogue over arms control or denuclearisation in the next three years. Although it remains unlikely that Tokyo or Canberra would play a defining role in negotiations with Pyongyang, Tokyo and Canberra should coordinate ahead of time to shape the President’s approach to negotiations based on their shared interest in North Korea’s complete denuclearisation.53 For this to be successful, Japanese and Australian policy-makers will need to leverage their relationships with key figures in the Trump administration to caution the President about the potentially negative consequences for their security if he strikes a deal without consulting them. However, given President Trump’s overall disregard for the interests of US allies, it remains uncertain how much real influence Japan and Australia could have on his thinking.

Given President Trump’s overall disregard for the interests of US allies, it remains uncertain how much real influence Japan and Australia could have on his thinking.

Moreover, it remains unclear whether North Korea would even consider returning to the negotiating table, given the noticeable policy shifts in Pyongyang. In October 2024, a North Korean envoy to the UN ruled out leader-to-leader diplomacy over its nuclear weapons program irrespective of the outcome of the US election.54 This echoes statements from Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un in September 2022 calling Pyongyang’s status as a nuclear weapons state “irreversible” and ‘non-negotiable”, which could render engagement without denuclearisation as a core priority leading to the implicit recognition of North Korea as a nuclear weapons state and legitimising its illicit sanctions evasion activities.55 The recent improvement of relations with Russia further decreases incentives for North Korea to come to the negotiating table, as Pyongyang will be able to mitigate the isolating effects of sanctions by exporting military equipment and natural resources to bolster Moscow’s war effort in Ukraine.

However, this does not mean that Australia and Japan should not try if the situation arises. Concerned about President Trump’s transactional approach towards allies during his first term, former Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo forged a friendship with President Trump that allowed Tokyo to exert influence over the United States’ approach to negotiations with North Korea during the 2018-2019 Korean Peace Process.56 Their close bond led President Trump to state that the United States was “behind Japan, our great ally, 100 percent” and to promise Abe that he would push for the release of 12 Japanese abductees during the 2018 Singapore Summit.57 Despite this, Abe’s assassination at a political rally in 2022 means that Japan can no longer leverage this bond to persuade the Trump administration to consider its interests. This presents an opportunity for Tokyo and Canberra to coordinate on how to fill the void to ensure that Trump does not strike a deal that leaves the two countries at greater risk to North Korea’s disruptive activities.

Lending Australian expertise to enhance Japan’s cyber-resilience

In the short term, decreasing Japan’s vulnerability towards information breaches from cyber-attacks is one area where Tokyo and Canberra can feasibly build resilience against Pyongyang.58 In recent years, North Korea has trained a highly sophisticated cyber army to help it evade sanctions and gather intelligence on its adversaries.59 In May 2024, Japan became a victim of a North Korean cyberattack when the TraderTraitor group gained access to Tokyo-based DMM Bitcoin that resulted in the theft of approximately US$308 million worth of cryptocurrency.60 The 2024 attack on DMM Bitcoin followed other attacks on Japan’s critical infrastructure. Both Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and the country’s largest port, the Port of Nagoya, have experienced repeated ransomware attacks since 2023, which has led the Japanese Diet to recently approve a bill on active cyber defence.61

Given Australia’s advanced cyber capabilities and its membership in the Five Eyes (FVEY) network, Tokyo and Canberra should consider declaring a ‘cyber partnership’ to assist Japan in aligning its policy frameworks and cyber-defence with FVEY standards. A proposed framework for a ‘cyber partnership’ aimed at reforming Japan’s cyber capabilities could emerge from existing cooperation through the Australia-Japan Cyber Policy Dialogue.62 Dispatching legal and cyber experts to Japan to advise and collaborate with government and private sector stakeholders would help align frameworks for cyber attribution and share information about cyber sanctions, thereby enhancing resilience against North Korean cyberattacks. While progress is being made on aligning policies and frameworks, Tokyo and Canberra should conduct regular bilateral cyber exercises and deepen trilateral exercises with the United States through Exercise Blue-Spectrum. This will help improve detection and response, hone the skills of Japanese cyber professionals, and enhance interoperability with their Australian counterparts.63

However, assisting Japan in aligning its cyber policy frameworks and cyber-defences with FVEY standards will not be problem-free. One significant issue relates to the technical constraints surrounding Tokyo’s ability to cooperate with foreign partners on offensive and defensive cyber warfare operations. Slow decision-making processes on intelligence reform, as well as the JSDF’s relatively small cyber defence command, may restrict the scope of cooperation required to enhance Tokyo’s resilience.64 Despite this, the recently approved bill on ‘active cyber defence’ that establishes a ‘cybersecurity council’ and a committee to oversee information gathering and analysis will provide the groundwork for Japanese cyber professionals to potentially work more closely with their Australian counterparts. Moreover, the cyber bill enables Japan to identify and neutralise the sources of cyber threats in spite of constitutional constraints, providing a starting point for both sides to deepen coordination on cyber warfare operations and enhance their resilience against North Korean infiltrations.65

Institutionalising a Track 1 Australia-Japan-South Korea trilateral

Another measure that Japan and Australia should adopt to enhance resilience against North Korea in the interim is to formally institutionalise the Australia-Japan-South Korea (AJK) trilateral. Holding the AJK biannually at the Track 1 level would signal to Pyongyang that, despite the deteriorating strategic environment in other areas of the Indo-Pacific, the Korean Peninsula remains a significant priority for both Tokyo and Canberra. The AJK would add another layer of resilience beyond the US-South Korea, US-Japan alliances and the US-Japan-South Korea trilateral, enabling the three countries to exchange information, close perception gaps and formulate joint responses to North Korean provocations. Similar to the Quad, any formal AJK dialogue could enable Tokyo, Canberra and Seoul to coordinate on keeping the United States engaged on the Korean Peninsula while streamlining responses to policies from the Trump administration that may increase or decrease their resilience against Pyongyang.

Therefore, to ‘smooth out the kinks’ towards establishing deeper habits of cooperation, Japan, Australia and South Korea should coordinate on enhancing their economic security in line with their highly interdependent trading relationships and shared visions for a free, open and rules-based Indo-Pacific.66 This may see Canberra, Tokyo and Seoul exchange information and design joint responses to potential supply chain disruptions linked to North Korean ballistic missile tests, cyber-attacks and incidents at sea. As geopolitical rifts deepen between China and US regional allies, reducing each other’s economic dependence on Beijing by encouraging the three countries to explore trade and investment opportunities among themselves, as well as with ASEAN member states and India, would enhance their resilience against economic retaliation if the trilateral defence agenda expands.

However, it remains an open question as to whether trilateral cooperation between Japan, Australia and South Korea without the United States’ participation is in each of their interests.67 This is because North Korea views Washington’s presence on the Korean Peninsula as the main cause behind its development of a nuclear deterrent. This leads Pyongyang to view the United States as the sole actor worth interacting with, which could render the AJK without the United States’ involvement as having little impact on changing North Korea’s behaviour outside of their existing alliances. Despite this, the trilateral’s broader agenda, which could include defence industry collaboration, trade and humanitarian assistance, may at least provide an outlet for all three countries to independently demonstrate opposition to provocations from Pyongyang and coordinate responses when they occur.

If the AJK does become institutionalised, managing potential flare-ups in tensions between Japan and South Korea, as well as ingrained habits of cooperation, will be paramount to ensuring that it survives long enough to be effective in building resilience against North Korea. There are sharp divides in opinion on closer relations with Japan between South Korea’s two major political parties. The conservative People’s Power Party (PPP) is receptive deeper engagement while the progressive Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) remains sceptical of Tokyo due to historical grievances.68 The ‘seesawing’ nature of South Korea’s relations with Japan has similarly correlated with periods of deepened interest and apathy in relations with Australia.69 Recent comments from DPK leader Lee Jae-myung about having no objections to deepened relations with Japan, however, suggest that South Korea could break with historical trends in its foreign policy as the balance of power on the Korean Peninsula becomes less favourable to Seoul.70

Strategic planning and crisis response: The largest area for growth?

Deterrence relies on the credibility of a state’s ability and willingness to respond to an armed attack.71 Possessing both the intent and capability to respond to a conflict on the Korean Peninsula can help deter North Korean provocations and allow for rapid deployment if deterrence fails. Since the signing of the RAA and the JDSC, a growing number of defence commentators have begun to describe the Japan-Australia relationship as an alliance in all but name, which has heightened expectations in the public domain regarding what security cooperation could and should achieve.72 Despite the main geographical focus of their alignment having been the Taiwan Strait and the East and South China Seas so far, Tokyo and Canberra may find themselves operating closely together in a hypothetical Korean contingency due to their respective alliance commitments to the United States.73 Therefore, both sides must envision ways to coordinate on strategic planning and logistics if a crisis escalates and, in a worst-case scenario, participate in joint combat operations around the Korean Peninsula.

Although the new “trilateral defence cooperation” and expanded joint exercises with the United States are important in this regard, Japan and Australia will need to deepen military-to-military coordination between the JSDF and the ADF to better secure their interests,74 including those vis-à-vis the Korean Peninsula. Bilateral security cooperation between Tokyo and Canberra remains the US-Japan-Australia trilateral’s “weakest link.”75 This integration gap raises questions about how both sides would and could respond jointly to a hypothetical Korean contingency. As it stands, their responses would be fragmented since Canberra would likely operate through the UNC in Korea and the ANZUS alliance, while Japan would probably operate through the UNC-Rear and the US-Japan alliance.76 Therefore, given the recent signing of the RAA, Tokyo and Canberra should discuss potential rotations of ADF assets and personnel through JSDF facilities and the UNC-Rear in the event of a conflict in the Western Pacific, including on the Korean Peninsula. There are precedents for an expanded ADF presence in Japan as Australia currently leads the UNC-Rear at Yokota Air Base in Tokyo, and ADF personnel were stationed at Hiro and Iwakuni in western Japan during the Korean War.77

Although the new “trilateral defence cooperation” and expanded joint exercises with the United States are important in this regard, Japan and Australia will need to deepen military-to-military coordination between the JSDF and the ADF to better secure their interests, including those vis-à-vis the Korean Peninsula.

Alongside discussing potential ADF rotations through Japan, Tokyo and Canberra should deepen consultations on integrating command and control between the JSDF and the ADF to effectively plan, coordinate and control joint forces and operations. As Japan is not a formal member of the UNC, the JSDF would most likely be expected to provide logistical and combat support to US and UNC forces (including Australia) in a Korean contingency.78 However, there may be scenarios where the JSDF and the ADF would need to coordinate with each other to assist the USAF, other UNC forces and even the Republic of Korea (ROK) Armed Forces. For example, the JSDF and the ADF could jointly conduct ISR in maritime waters around the Korean Peninsula, protect sea lanes of communication on the approaches to the Peninsula, escort US vessels traversing between Japanese and Korean naval ports, and even provide air support to US and UNC forces on the ground in Korea.

Therefore, to enhance the degree of interoperability required for any joint response to a hypothetical conflict in the Western Pacific, including on the Korean Peninsula, Japan and Australia will need to deepen bilateral military exercises and increase operational intelligence sharing. Widening the scope of naval exercises to include the RAN and JMSDF’s submarines could help complement the growing interoperability achieved by the RAN and JMSDF’s ships through Operation Nichi-gou Trident.79 This would help both navies become as interoperable as they are with the USN to better enable any integrated response. Moreover, holding Exercise Bushido Guardian biannually could enable the RAAF and JASDF to conduct more sophisticated missions and exercises applicable to conflict scenarios on the Korean Peninsula and elsewhere, such as bilateral ISR, refuelling exercises and other joint exercises that simulate both sides providing air cover to assets at sea.

Planning for worst-case scenarios on the Korean Peninsula will also require Australia’s rapid integration into the United States and Japan’s IAMD architecture. Tokyo and Canberra’s likely focus on protecting sea lanes of communication in a hypothetical Korean contingency could result in merchant vessels and/or JSDF and ADF assets becoming legitimate targets for North Korean ballistic missiles. Alongside continuing frequent simulations on IAMD command and control between the United States, Japan and Australia, Canberra should offer Tokyo the use of Australian missile testing ranges, such as the Woomera Testing Range in South Australia and other facilities, to test and evaluate Japan’s long-range conventional strike capabilities, including Tomahawk cruise missiles.80 Granting Japan access to Australian missile testing ranges would help the JSDF and ADF integrate their missile capabilities and industrial defence bases while providing Tokyo with the opportunity to test longer-range missiles without jeopardising the safety of its citizens or exposing vital intelligence to its rivals.81

However, Australia and Japan must address a range of perception, logistical and coordination issues before they can effectively respond together in a hypothetical contingency, either on the Korean Peninsula or elsewhere. The first hurdle will be moderating institutional preferences to prioritise coordination with the United States over collaboration with each other.82 To remedy this, there must be shifts in deeply rooted perceptions regarding the limits of security cooperation within their respective policy-making institutions, which have been influenced by the prolonged negotiations over the RAA and the lingering ‘trauma’ regarding the unsuccessful Soryu class submarine bid.83 However, the institutional shocks resulting from the Trump administration’s reversal of the United States’ approach towards NATO, combined with the potential boost to the security partnership if Japan’s bid for Australia’s acquisition of the Mogami class frigate is successful, may serve as catalysts to break longstanding habits of over-reliance on Washington and mitigate institutional pessimism about the limits of bilateral security cooperation.84

The second issue relates to logistical challenges that complicate discussions of potential ADF rotations through Japan and the hosting of more frequent and sophisticated military exercises. The RAA has only recently come into force and there are differing views among Japanese and Australian officials regarding how it should be implemented and the types of activities that it permits.85 As Australia is geographically distant from the Korean Peninsula but directly engaged through the UNC and ANZUS, questions remain about the type of support that Canberra would and could offer Japan in the event of a contingency. Strategic planners in Tokyo and Canberra will then need to assess their respective comfort levels and clarify their expectations of one another’s roles. Minimising organisational and communication differences to ensure an adequate level of integration will also be key for any joint response, provided policymakers decide that this is in their best interests.86

Enhancing confidence and testing comfort levels between Tokyo, Canberra and Seoul regarding strategic planning and crisis response should be a core priority.

Regular consultations with the United States and South Korea will be crucial for understanding their views on Japan and Australia’s role in any hypothetical Korean contingency. While any JSDF involvement will likely be limited to support roles, addressing Seoul’s concerns, especially regarding a renewed Japanese presence on and around the Korean Peninsula, is vital for ensuring that any threat to intervene is perceived as credible by North Korea and its allies. Thus, enhancing confidence and testing comfort levels between Tokyo, Canberra and Seoul regarding strategic planning and crisis response should be a core priority. Institutionalising the AJK trilateral and regularly holding more informal Track 1.5 dialogues would be significant steps towards establishing the frameworks to facilitate such discussions in this regard.

Conclusion: Closing the gap

Although Japan and Australia have deepened their security cooperation in recent years, significant capability gaps and mismatches in strategic priorities still persist at the bilateral level, which could complicate a joint response to future conflict scenarios in the Indo-Pacific. The escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula serve as a notable case. This report has aimed to draw greater attention to existing gaps and mismatches and envisioned ways to close them. It suggests the following policy recommendations to best coordinate their efforts in dealing with growing tensions on the Korean Peninsula, some of which can be applied to other flashpoints where their interests are sufficiently engaged, such as the Taiwan Strait and the East China Sea.

- Japan and Australia should consider the possibility that the Trump administration will engage North Korea in dialogue over its nuclear weapons program, and if it does, jointly coordinate on how to pre-emptively shape the United States’ approach towards negotiations.

- Japan and Australia should aim to build their resilience against North Korean cyber-attacks and supply chain disruptions in the short term by:

- Lending Japan Australia’s expertise in cybersecurity by declaring a ‘cyber partnership’ that aims to align Tokyo’s cybersecurity policy frameworks with Five Eyes standards.

- Institutionalising a Track 1 trilateral dialogue with South Korea to consult, exchange information and design joint responses to potential supply chain disruptions linked to North Korean ballistic missile tests, cyber-attacks and incidents at sea.

- In the longer term, Japan and Australia should aim to strengthen joint planning for a future Korean contingency to deter and respond to, if necessary, a hypothetical North Korean attack on South Korea and US forces stationed on the Korean Peninsula and in Japan by:

- Commencing discussions about potential rotations of Australian Defence Force (ADF) assets and personnel through Japan Self-Defense Force (JSDF) facilities in Japan, as well as those designated by the United Nations Command-Rear in the event of a contingency.

- Deepening consultations about integrating command and control between the JSDF and the ADF to effectively plan, coordinate and control joint forces and operations.

- Widening the scope of naval and air exercises, as well as operational intelligence sharing, between the JSDF and the ADF to enhance the degree of interoperability required for combat support missions on and around the Korean Peninsula in the event of a worst-case scenario.

- Ensuring Australia’s rapid inclusion into the United States and Japan’s Integrated Air Missile Defence (IAMD) architecture by offering the JSDF the use of Australian missile testing ranges to facilitate deeper integration of Japan’s and Australia’s missile capabilities and industrial defence bases.

While ambitious, it remains important that any proposal for greater coordination on the Korean Peninsula considers the geographical and resource constraints of both sides while keeping pace with developments in their respective alliances with the United States and partnerships with South Korea. Therefore, before formulating and implementing measures that enable a joint response, policy professionals and defence planners will need to engage in deeper dialogue to close threat perception gaps and better pinpoint where their interests converge and diverge. This is where this report aims to contribute by providing a foundation from which an agenda can be developed to achieve the necessary degree of coordination in responding to the deteriorating strategic situation on the Korean Peninsula.

Preparing for a protracted maritime war: The strategic case for Japan-Australia naval industry cooperation

Rintaro Inoue

Research Associate at the Institute of Geoeconomics

Rintaro Inoue is a Research Associate at the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG), a Tokyo-based global think tank, where his research focuses on the defence policies of the United States, Japan and Australia. His recent work has been published in The Washington Quarterly, the Journal of the Japan Association for International Security, The Japan Times, Ships of the World, and ASPI’s The Strategist. He holds a Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts in Law from Keio University, where he is currently pursuing a PhD. He received the 2024 Best Newcomer Paper Award from the Japan Association for International Security for his article, “Postwar U.S. Defense Strategy in the Asia-Pacific: The Role of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Pacific Fleet in the Making of ANZUS.”

Executive summary

- Japan and Australia’s defence posture would face its most severe test in the event of a high-intensity, protracted US-China war over Taiwan. While US strategic discussions have traditionally focused on surviving a short and sharp conflict, recent attention has shifted toward the challenges of sustaining a protracted war. Reflecting this shift, strategic communities in Australia and Japan have begun emphasising the need to enhance resilience and preparedness for long-term warfare. Nevertheless, neither country has developed comprehensive strategies or analyses for sustaining military operations during an extended conflict. Bilateral defence cooperation between Japan and Australia can potentially address this issue.

- Since the inception of the Self Defense Forces (SDF), Japan has structured its defence strategy around the expectation that the United States would serve as the ‘arsenal of democracy’ in the event of a protracted war. This has resulted in chronic underinvestment in Japan’s war sustainment capabilities. However, the current state of the US defence industrial base, particularly in the maritime domain, has significantly weakened to the level that Japan must reexamine its long-held assumption.

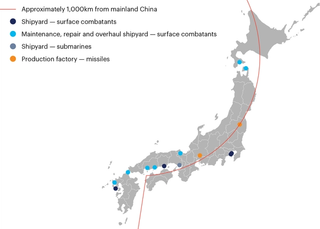

- In recent years, Japan has taken steps to enhance its defence industry capability and capacity. However, these efforts have not been focused on ensuring the sustainment of operations during wartime. Moreover, the lack of strategic depth makes the entire defence industrial base vulnerable to Chinese attacks, constraining the SDF’s ability to rely on domestic production alone.

- A logical alternative is for Japan to collaborate with Australia, which is making significant investments in its defence industrial base and benefits from a strategic depth that Japan lacks. By working together, Japan and Australia can address these vulnerabilities. To this end, the two countries should pursue cooperation in the following areas.

Key policy recommendations

- Japan and Australia’s bilateral defence cooperation should prioritise developing Australian shipyards capable of servicing Japanese destroyers. Selecting the Upgraded Mogami class for SEA 3000 would enable Australian shipyards to stock critical components and gain in-depth knowledge of the vessel.

- Both governments must be prepared to adapt rapidly in the event of a protracted war, including examining scenarios in which a significant portion of allied surface combatants are damaged or sunk. The two navies should also explore how to continue fighting effectively if most of their current fleets are neutralised. In this context, joint efforts to develop and integrate unmanned surface vessels, which governments are already pursuing through separate initiatives, could prove especially valuable.

- Japan and Australia must engage the United States to emphasise the critical importance of allied sustainment capabilities in a protracted war and seek cooperation from the United States in strengthening them. Persuading the US Navy to service its destroyers in Australian shipyards, rather than in Northeast Asia during peacetime, would help strengthen the Australian industrial base.

Introduction

The Japan-Australia relationship is officially described as a “Special Strategic Partnership,” yet it lacks a widely shared strategic rationale for in-depth defence cooperation. This absence of a clear framework creates uncertainty regarding the scope of cooperation and the division of labour in wartime, despite both countries’ commitment to “consult each other on contingencies that may affect [their] sovereignty and regional security interests.”87 This paper argues that Japan-Australia defence cooperation should be structured to effectively complement each country’s respective weaknesses, particularly in the context of a protracted US-China war over Taiwan.

The bilateral defence relationship between Japan and Australia has increasingly taken on the characteristics of an alliance, rather than the quasi-alliance it had long been described as. Both Japan’s and Australia’s national defence strategies have emphasised the value of the relationship with the latter, describing Japan as “indispensable”.88 The two governments have also agreed to station liaison officers in each other’s command centres and Japan has been conducting asset protection missions for Australian vessels.89 Despite the significance of this growing defence cooperation, expert discussions on the strategic rationale behind closer bilateral defence coordination remain insufficient. In particular, there has been limited examination of how Japan and Australia would collaborate in a conflict scenario. Amid increasing uncertainty over US commitments, Japan and Australia must not only deepen their defence cooperation but also strategically align their efforts. Strengthening collective deterrence, enhancing defence capabilities and clarifying the division of roles in wartime will be critical to mitigating defence risks.

The Japan-Australia defence cooperation should be structured to enable both countries to offset each other’s strategic and operational weaknesses, as both face distinct yet significant defence challenges. Since the release of its three strategic documents in 2022, Japan has focused on enhancing military effectiveness through seven key pillars, including “sustainability and resiliency.” Similarly, Australia’s 2024 National Defence Strategy prioritises strengthening maritime capabilities. However, both nations face structural constraints: Japan, with its limited resources and strategic depth, struggles to sustain prolonged military operations, while Australia, despite its plans to more than double its fleet, lacks the domestic shipbuilding capacity to achieve this objective.

By leveraging their respective strengths, Japan and Australia can work together to mitigate these weaknesses, creating a more resilient and complementary defence posture. Through strategic coordination and targeted cooperation, both nations can enhance their overall defence capabilities and achieve a synergistic effect in their defence enterprise.

While submarines, fighter aircraft and unmanned assets are indispensable in a Western Pacific conflict, surface combatants warrant particular attention due to their high versatility and critical role in protecting sea lines of communication, which are vital to Japan’s survival.

The following sections will examine how Japan can prepare itself for sustained operations in a protracted conflict by focusing on cooperation with the Australians in the repair and acquisition of platforms, particularly surface combatants. While submarines, fighter aircraft and unmanned assets are indispensable in a Western Pacific conflict, surface combatants warrant particular attention due to their high versatility and critical role in protecting sea lines of communication (SLOC), which are vital to Japan’s survival.90 This paper will then explore the potential for Japan-Australia cooperation in naval shipbuilding and repair, with the dual objective of enhancing Australia’s shipbuilding capacity and providing Japan access to a secure defence industrial base in a protracted war.

A long war in the Western Pacific?

The scenario that would place the greatest level of stress on the defence of Japan and Australia would be a high-intensity and prolonged US-China war over Taiwan. The US strategic community, which has led the discussion about a potential US-China war triggered by a prospective People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) invasion of Taiwan, has traditionally focused on surviving a short and sharp war. For years, tabletop exercises focusing on the initial weeks of the war have provided valuable insights, highlighting the critical importance of the resiliency of defence infrastructures to survive the first strike and underscoring the role of allies, particularly Japan, in contributing from the earliest stages of the conflict.91 Recently, however, the scope of these discussions has expanded to the post-initial stage of the conflict, to include studying how to win a protracted war.92 The US Naval Institute has been at the forefront of this shift, spearheading the conversation through its “American Sea Power Project.” This initiative focuses on the second phase of a five-phase framework of war: the initial fight, recovery, seizing the initiative, the long campaign and war termination.93 In line with this broader perspective, many US strategists and defence industry leaders are now advocating for developing a robust defence industrial base capable of sustaining a high-intensity, multi-year conflict.94

This shift in focus can be attributed to four key factors. First, there is a growing recognition that wars among major powers historically tend to last longer than initially intended or expected.95 Second, Ukraine’s unexpected success in resisting Russian aggression underscores how militaries in a disadvantaged position can endure an initial assault from a stronger adversary — often due to the adversary’s miscalculations — thereby increasing the likelihood of a prolonged conflict.96 Third, strategists have increasingly acknowledged that China’s defence industry has already effectively adopted a wartime posture while the United States struggles to match its pace.97 Notably, China’s shipbuilding industry boasts a production capacity 230 times greater than the United States’.98 Finally, there is a shared understanding within the strategic community that neither the United States nor China is likely to back down after incurring significant losses, further raising the likelihood of a protracted war.99

Inspired by these discussions, strategic communities in Australia and Japan have also begun to explore the possibility and implications of a prolonged war. Australia’s strategic documents emphasise efforts to secure fuel supplies, strengthen supply chains and improve the resilience of its military bases.100 Yet, there has been little discussion on a theory of victory in the event of a prolonged conflict.

Similarly, in Japan, the importance of sustaining military operations has been recognised, leading to progress in the procurement of equipment parts and ammunition. However, the focus remains on stockpiling these resources during peacetime, and discussions on how to procure them in wartime remain insufficient. While there are some ongoing discourses regarding a protracted war, these tend to centre on energy and food security rather than military strategy or operational aspects.101

To date, no publicly available study has comprehensively addressed the military issues that Japan and Australia would face in sustaining a prolonged war. Given the likelihood of a protracted maritime conflict in the Indo-Pacific region, the two governments must take the prospect of a protracted war seriously and better align their defence strategies to address this challenge. Without significant policy shifts and deeper analysis, these nations risk being unprepared to meet the demands of a high-intensity, long-duration conflict.

Assessing Japan’s viability in a protracted war

In December 2022, the Japanese Government released its National Defense Strategy, acknowledging the significant deterioration in the security environment due to the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and rising tensions in the Taiwan Strait.102 The strategy identified military “sustainability and resiliency” as one of the seven essential capabilities, emphasising the need to improve the Japan Self Defense Forces’ (JSDF) ability to “continue persistent activities in contingencies.”103 Importantly, these measures were not aimed at bolstering the JSDF’s capability to fight a protracted war. Instead, they were focused on enhancing readiness by addressing long-standing deficiencies in the procurement of equipment parts and ammunition.

As most militaries do, the JSDF has plans to rapidly increase all its platforms’ readiness in times of emergency and hold enough spare parts and ammunition to conduct a pre-determined number of missions. However, prior to 2019, JSDF’s readiness was worsening every year. Due to a shortage of spare parts, it was forced to cannibalise other platforms for interchangeable components to keep operating others.104 Although this practice has been adopted by many militaries and organisations for its short-term effectiveness, it significantly undermines overall fleet readiness in the medium to long term.105 While the prevalence of this practice has been decreasing since 2019, the Ministry of Defense estimates that an acceptable level of readiness will not be reached until 2027.106

Ammunition storage has also been reported to be in dire condition. In 2015, high-ranking officials in the Ministry of Defense were anxious whether the JSDF could fight for two weeks should Japan get involved in a war with China.107 It was reported that, in 2022, while the JSDF was required to have three months’ worth of ammunition stockpiles, it had only two months’ worth.108 Even missiles for ballistic missile defence operations against North Korea, which the JSDF have been on high alert for since 2016, were low in stock. The Ministry of Defense revealed that the JSDF only had 60% of the required missile capacity for ballistic missile defence operations.109

The limited availability of spare parts and ammunition stems from a defence procurement strategy that prioritises large platforms, such as Aegis destroyers and F-35s, over sustainment resources. Since 2010, the JSDF has concentrated on presence and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions mainly in the Indo-Pacific region, aimed at shaping China and North Korea’s actions and fostering a favourable security environment.110 This strategy did not require the active use of live ammunition or high-end mission-capable readiness. Instead, it required platforms to be capable of conducting basic missions, driving the procurement trend to be focused on acquiring large platforms.111

Japan has historically overlooked the procurement of spare parts and ammunition, a trend that dates back to the Cold War.112 This tendency can largely be attributed to budgetary constraints, a perceived lack of urgency and a shared strategy established between Japan and the United States at the JSDF’s inception, which tasked the JSDF with holding the line and enduring the fight until US reinforcements and military aid arrived.113 This intentional division of roles was designed to maximise the alliance’s effectiveness, with Japan prioritising immediate defensive operations while relying on United States support for sustained operations.

Strengthening collective deterrence, enhancing defence capabilities and clarifying the division of roles in wartime will be critical to mitigating defence risks.

Therefore, between 1978 and 1981, one scenario projecting a Soviet invasion of Hokkaido set the ammunition stockpile target at only two weeks’ worth.114 Within this strategy, the role of the Japan Ground Self Defense Force (JGSDF) and Japan Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) primarily focused on halting invading forces to the greatest extent possible, while the Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) concentrated on securing nearby SLOCs. Protecting SLOCs was deemed critical to enable US carrier strike groups and supply ships to deliver reinforcements and war materiel.115 In 1985, under US pressure, Japan made efforts to improve ammunition stockpiles and enhance the JSDF’s ability to hold the frontlines for a longer period.116 However, these measures achieved only limited success, largely because the Cold War ended just five years later, diminishing the perceived urgency for such preparations.

Should a war extend beyond Japan’s sustainment capabilities, it has long been assumed by both Japanese and US thinkers that the United States would supplement the depleted equipment and ammunition, acting as the “arsenal of democracy” as it did throughout much of the 20th century. This notion is underpinned by the US strategic reserve of weapons, including armoured vehicles and aircraft, which were maintained in large stocks and provided to allies and partners during the Cold War. This premise is explicitly reflected in the 1978 and 1997 Guidelines for the Japan-US Defense Cooperation, which state that “the United States will support the acquisition of supplies for systems of US origin while Japan will support the acquisition of supplies in Japan.”117 Since most of Japan’s high-end weapon systems were designed by the United States and used interoperable ammunition, this arrangement effectively ensured that Japan would rely on munitions and weapons supplied by its ally.

Since 2022, the Japanese Government has taken initial steps to enhance the JSDF’s sustainment capabilities, informed by lessons from the conflict in Ukraine. The Ministry of Defense has announced plans to begin long-term storage of certain equipment, a process known as mothballing, starting in fiscal year 2025, to prepare for a protracted war. However, this initiative is extremely limited in scope, targeting only 30 Type 74 and Type 90 tanks, as well as the Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS).118 Crucially, equipment essential for achieving naval and air superiority — such as surface combatants and aircraft — remains excluded from mothballing plans. As a result, the JSDF continues to face significant constraints in its ability to sustain operations during an extended conflict, hindered by long-standing premises in the strategic level planning.

Weakened “arsenal of democracy”

Even today, much of Japan’s strategic community appears to operate under the assumption that the JSDF would rely on US equipment and ammunition in the event of a prolonged war. More concerningly, there seems to be little consideration of how Japan would sustain its operations after three months into the conflict. Publicly available tabletop exercises and government studies predominantly focus on the initial weeks of a war or the pre-war phase, leaving critical questions about long-term sustainability unanswered.119 Japan’s strategic community must grapple with whether the United States currently possesses sufficient stockpiles or the defence industrial base capacity to support both its own military operations and those of the JSDF during a protracted, high-intensity conflict in the Western Pacific.

Unfortunately, as many American strategists have correctly observed, the United States currently lacks the equipment and ammunition necessary to sustain its own military operations during a protracted war, let alone support allied militaries.120 Although much of the data on US stockpiles remains undisclosed, think tank reports highlight critical gaps. For example, essential missiles like the Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM) are projected to be consumed at an alarmingly high rate, with supplies likely to last only a week in a high-intensity conflict.121 Other analyses reveal that while the US Navy would require approximately 2,000 anti-ship missiles to neutralise PLA naval forces in the first two months of a war, it only has around 1,000 missiles in stock.122 This shortfall underscores the harsh reality that there would be minimal ammunition available for Japan in such a scenario.

As for equipment, the United States is likely to encounter significant challenges in sustaining a protracted maritime war. While thousands of vehicles are stored for long-term ground warfare, these assets will have little relevance in a conflict where maritime and air superiority are paramount. In terms of aircraft, the United States stores hundreds in the Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG) ‘boneyard’. Many of these aircraft are classified under categories that allow them to be restored to airworthy conditions with varying levels of maintenance, ensuring some degree of readiness for air combat.123

However, the outlook for surface combatants is far less promising. According to the US Navy, fewer than 20 ships are currently held in reserve under the classifications of “out of commission in reserve” or “out of service in reserve.”124 Approximately half of these are Ticonderoga-class missile cruisers, which remain classified as reactivation candidates. Unfortunately, due to years of inadequate maintenance, many of these vessels are in poor condition and require substantial modernisation.125 In addition, seven Littoral Combat Ships are also listed as reactivation candidates. While they remain seaworthy, their limited combat capabilities make them ill-suited for high-intensity maritime warfare. Even if these ships were successfully refurbished and recommissioned during a conflict, they would likely be prioritised for the US Navy rather than the JMSDF, as the United States would also need to regenerate its own fleet. This leaves the JMSDF with limited options for receiving equipment support from the United States during a protracted war.

Moreover, the timely delivery of equipment and ammunition cannot be assured, even if the United States were to mobilise its shipyards after the onset of war. US shipbuilding capacity dwindled to less than 0.5% of China’s shipbuilding output and shrank by over 80% since the 1950s.126 Additionally, the number of shipyards capable of constructing naval vessels has decreased from 11 during the Vietnam War to just four today.127 This severe decline in capacity undermines the United States’ ability to regenerate its fleet in a meaningful timeframe during a high-intensity, prolonged conflict. Furthermore, US naval shipbuilding has been plagued with delays of major surface and subsurface construction programs.128 According to a report on a tabletop exercise that the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party conducted, the time required to replace lost ships has become so long that it is unlikely to effectively impact the course of a prospective war.129

This severe decline in shipbuilding capacity undermines the United States’ ability to regenerate its fleet in a meaningful timeframe during a high-intensity, prolonged conflict.

The US Congress’ efforts to reform the shipbuilding sector through the Shipbuilding and Harbor Infrastructure for Prosperity and Security for America Act (SHIPS Act) represents a step in the right direction for addressing longstanding issues in the US shipbuilding industry.130 This initiative, if successful, could strengthen the US Navy’s capacity to expand and regenerate its fleet. However, these reforms are long overdue and face significant challenges in implementation, given the decades of neglect and reduced capacity in this sector.

Even if the SHIPS Act achieves its objectives, the time required to see tangible increases in ship production capacity will likely be too long to address immediate or near-term military needs. Moreover, it remains uncertain whether these reforms would yield sufficient capacity to not only meet the demands of the US Navy but also provide substantial support to allies, including Japan, in a protracted conflict scenario.

This reality necessitates a critical reassessment by US maritime allies of their dependency on American equipment and ammunition in the event of a protracted war. Japan and even Australia should consider operating under the assumption that the United States will only be able to provide military aid on a much more limited scale than previously anticipated.

Japan’s defence industry vulnerabilities

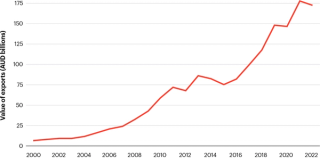

If the United States can no longer be relied upon to sustain protracted maritime conflicts, Japan must take steps to bolster its own defence industry capacity and capabilities. However, current indicators suggest this may be challenging. Japan’s defence industry already faces acute capacity and supply-chain constraints even in peacetime. In response, the Ministry of Defense has introduced several initiatives aimed at reinforcing the defence industrial base, promoting the export of defence equipment, and enhancing technological foundations. These measures seek to strengthen supply chains and improve the operational capabilities of the JSDF.131 While the defence sector appears to be making progress — evidenced by a defence-related sales increase of up to 25% at major companies from fiscal year 2023 to 2024 — these gains remain insufficient to fully meet the demands of a prolonged conflict.132

Despite current defence industry policies showing some success in producing domestically manufactured equipment, challenges persist for hardware produced under license from the United States. For example, Japan aims to double its annual production of PAC-3 missiles from 30 to 60 units to replenish stockpiles, but progress has stalled due to delays in receiving critical components from the United States.133 Similar challenges extend to other missiles and equipment, complicating efforts to strengthen overall defence capability.134 Moreover, under the US Defense Priorities and Allocations System (DPAS), Japan and other allies are required to wait until domestic US demand is met, further delaying the delivery of essential components.135

Capacity and supply chain issues are likely to worsen, as scaling up production requires significant time, and conflicts increase the risk of disruptions.136 Even a single failure within the supply chain can halt production entirely. For example, the construction of JMSDF destroyers involves approximately 8,300 companies, many of which rely on specialised skills or equipment. Replacing these highly specialised firms is extremely difficult, underscoring the vulnerability of the current defence production system.137