Executive summary

Over the next ten years, developments in the Indian Ocean will become more central to the driving economic, diplomatic and competitive dynamics shaping Australia’s regional security environment. The Australian Government has long recognised the Indian Ocean’s connectedness to affairs in East Asia and the Pacific, advancing an integrated strategic concept as early as 2013. However, to date, the stark realities of resource scarcity and a bias towards Australia’s Pacific coastline have constrained Australia’s agenda for the Indian Ocean region. The expansive, complex and under-institutionalised nature of the region has meant that Australian officials have depended on costly bilateral diplomacy, with mixed results.Today, the limitations of Australian partners’ capacities for Indian Ocean engagement are becoming plainer. The Australian Government stands at an inflection point where it must reconceive its approach to its so-called ‘second sea’. A new toolkit must be developed to dispel strategic risks and embrace burgeoning economic and diplomatic opportunities.

By assuming the lens of integrated statecraft, this report argues that the Australian Government must advance a cohesive strategy across multiple lines of effort to shape strategic dynamics across the Indian Ocean. Accepting that Australia cannot dramatically increase the resources available to underwrite this approach, an effective regional strategy will depend on both cooperation and deconfliction with like-minded partners. The report recommends a number of principles to drive diplomatic, economic and security engagement in the theatre independently and collectively over the next decade:

Diplomatically, Australia should:

- Strengthen political representation

Building on the recent appointment of an Indian Ocean Envoy, appoint an Assistant Minister for the Indian Ocean to elevate regional engagement, akin to ongoing efforts in its Pacific strategy. - Expand diplomatic presence

Strengthen diplomatic posts in the Indian Ocean, especially in small states, enabling deeper engagement and supporting more frequent senior-level visits. - Prioritise targeted minilateralism

Focus on effective minilateral partnerships in the Indian Ocean, whose arrangements offer more practical opportunities for maritime cooperation than broader multilateral forums and provide flexible options, including without US involvement, for engaging non-aligned partners. - Reassess development role

Regularly reassess development aid to fill gaps left by the recent decline of traditional contributions from partners like the United States and the United Kingdom, leveraging Australia’s credibility to make strategic, high-impact investments. - Deepen coordination with partners

Enhance planning and coordination with intra-regional and extra-regional partners, including France and the United Kingdom, on diplomatic and non-traditional security efforts in the western Indian Ocean, contributing selectively where Australian involvement can provide the greatest value add.

Economically, Australia should:

- Develop a comprehensive Indian Ocean Economic Strategy

Create a dedicated Indian Ocean economic strategy as a successor to the 2018 India strategy, to both clarify and grow momentum around trade and investment priorities for smaller Indian Ocean states. - Support regional port infrastructure

Help develop port infrastructure in small states, in partnership with the private sector with a focus on decarbonisation, digitalisation and operator capacity-building to stimulate intra-regional trade. - Strengthen blue economy security

Increase collaboration with local governments in the Indian Ocean region to counter illegal fishing, piracy and other maritime threats by enhancing information sharing and maritime surveillance. - Promote economic multilateralism

Support greater economic integration across the Indian Ocean, engaging existing select multilateral forums to more effectively encourage regional economic cooperation.

In the security sphere, Australia should:

- Ensure AUKUS supports a regional balance of power in the Indian Ocean

Ensure AUKUS makes a purposeful contribution to ensuring Indian Ocean stability by investing in the necessary partnerships, infrastructure, workforce and public support to make the program sustainable. - Accelerate force posture initiatives

Fast-track the development of key defence facilities in Cocos-Keeling Islands and Northwest Western Australia. - Deepen trilateral operations

Pursue trilateral P-8 maritime surveillance operations with India and the United States, leveraging Australia’s Indian Ocean territories for strategic advantage. - Explore opportunities for deeper security cooperation within the Quad

Place more focus on security-related cooperation opportunities in the context of the Quad grouping, including maritime domain awareness (MDA), intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (ISR), and anti-submarine warfare (ASW). - Expand maritime cooperation with northeast Indian Ocean players

Build on the Guardian-class Patrol Boat transfer to the Maldives by evolving the Pacific Patrol Boat Program into an Indo-Pacific model, extending support to other northeast Indian Ocean states.

Introduction

Australian strategists, from their vantage point in Canberra near Australia’s eastern coastline, have long concentrated on the partnerships and prospective challenges of the Pacific Ocean. As a result, the Indian Ocean extending from Australia’s western coastline has inspired fewer resources and less strategic concern. Indian commentators have long bemoaned the global attention deficit in the Indian Ocean — despite many countries’ adoption of an ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept.1 This is not to say that the Indian Ocean has not been an unerring area of concern for Australian naval operations. With little fanfare, the Albanese government has released strategic documents that make plain its interest in renewing Australia’s focus on Indian Ocean waters and positioning Australia as a capable and consistent partner to the littoral and island countries of the Indian Ocean region.2

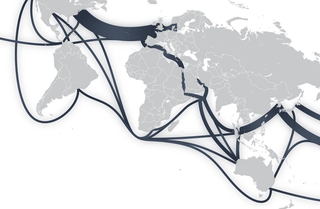

Few could argue against the significance of a stable and economically dynamic Indian Ocean to Australia’s interests. The region encompasses more than 70 million square kilometres and three billion people. Over half of the world’s container shipping and over 80% of global maritime oil trade pass through its waters.3 On its coastline, 40% of global offshore oil production occurs — with 65% of global oil reserves vested in ten Indian Ocean states. The Malacca Strait and Strait of Hormuz are among the most significant trade routes in the world, and the difficulties of ensuring secure passage through these choke points increasingly preoccupy Australia and its partners.4

Still, despite the best efforts of successive foreign ministers5 and defence ministers6 hailing from Western Australia, the nation lacks a strategic outlook for its so-called “second sea” commensurate with its current and future importance to Australian policy objectives.7 Former Foreign Minister Julie Bishop recently wrote that “the Indian Ocean part of our foreign policy remains a work in progress.”8 This assessment is reflective of the fact that Australia’s strategic approach to the Indian Ocean remains iterative and ad hoc, even as diplomatic initiatives for the region have unfurled with greater urgency in recent years. The refrain that an increasingly multipolar regional order and intensifying strategic competition are challenging strategic objectives across the Indo-Pacific may be familiar. However, the increasingly capable People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), the continuation of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) Belt and Road projects and a fraught China-India relationship have increasingly underscored that Australia’s strategy in the Indian Ocean region requires dedicated reform. The Australian Government’s answer to such challenges off its western coastline is complicated by the reality that, of all parts of the Indo-Pacific, the Indian Ocean is the area where Australia’s defence partnership with the United States offers the weakest security convergence. Today, Australia must reconcile the simultaneous priorities of maintaining its status as partner of choice in the Pacific with the demands of India’s growing appetite for engagement, changing US expectations of Australia’s role in the Indo-Pacific region and increasing demands on Australian national interests in the Indian Ocean region. In short, Australia requires a new Indian Ocean agenda for the next decade.

Expanding Australia’s Indian Ocean engagement is a complex undertaking; the diversity of Indian Ocean countries, the size of the region, its economic and diplomatic organisation into largely continental-driven groupings in South Asia and the Middle East (despite the defining feature of the Indian ocean),9 and the pace of change in the regional balance of power continue to complicate Australia’s long-term policy thinking. The scarcity of effective and inclusive regional institutions, especially in contrast to a highly institutionalised Southeast, means that Australia’s familiar toolkit for multilateral engagement must often be traded for taxing bilateral efforts. The challenge then for right-sizing Australia’s Indian Ocean strategy is considering available resources; anticipating the current and future demands of Australia’s partners; and presiding over a division of labour amongst other aligned major and middle powers in the region.

This report undertakes to examine the key features of Australia’s prevailing Indian Ocean strategy and to set out objectives for the next decade. It reflects insights gained in Track 1.5 and Track 2 workshops held in three countries, more than 20 meetings with regional experts and officials, and seven commissioned research publications from Australian, Indian and American authors. This report is focused on providing an assessment on Australia’s engagement on the region through an ‘integrated statecraft’ approach. It begins by baselining Australia’s Indian Ocean identity and its contemporary strategic context. It then proceeds in three chapters, covering the diplomatic, economic and security dimensions of Australian strategy in the coming years to provide an agenda for future action.

Australia’s Indian Ocean identity

An Indian Ocean focus has long been absent from Australian strategic policy. While Soviet naval task forces in the region kept the Australian Defence Force (ADF) focused on discrete missions during the Cold War, the post-Cold War era of US global hegemony saw a relatively benign Indian Ocean region drift from Australia’s list of priorities. During the Global War on Terrorism, Middle East operations were at the fore for Australia and its partners, while Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief missions and peacekeeping operations closer to home were focused on the South Pacific. Southeast Asia loomed large as a key region for partnerships, engagement exercises and presence operations, but US regional dominance and ASEAN centrality meant that the Indian Ocean aspects of Southeast Asian engagement were seldom pronounced.

During this period, the Indian Ocean was treated as Australia’s ‘second sea’. Wrapped in a reassuring cloak of US maritime dominance and growing Indian power, the Indian Ocean region was dwarfed in Australian strategic circles by an overwhelming focus on the Pacific. This was enabled by a long-held perception of Australia’s strategic identity being firmly anchored in an Asia-Pacific understanding of its geography. This was understandable. Australia is part of the Southwest Pacific family; its roles and responsibilities in this region - culturally, economically and politically - are well known. As a result, Australia’s engagement in the Indian Ocean is far less pervasive in the national consciousness. Except for Western Australians, the bulk of the population resides over 3,500km distant from the Indian Ocean, leaving it far from their consciousness.

The last time the Indian Ocean loomed large in Australia’s strategic consciousness was in the period of the British Empire and the early Cold War, when the sea lines of communication, supply and reinforcement from the United Kingdom arched across this ocean and through the Middle East, making their preservation an essential part of British, and thus Australian, maritime power. Australia’s first major naval action, the sinking of the German cruiser the Emden, was fought in the Indian Ocean, HMAS Sydney (II) disappeared in November 1941 off the Western Australian coast in the nation’s greatest naval tragedy while the first, and later second, Australian Imperial Force sailed across the vast expanses of the Indian Ocean to the battlefronts in the Middle East, the Western Front and the Mediterranean. However, the war in the Pacific, the fall of Singapore, and the shift from a UK to a US alliance partnership in the Second World War and the post-Cold War era dragged Australia’s strategic gaze northward and eastward.

In Australia’s strategic debates, many commentators have also noted Australia’s long history of ‘sea blindness’.10 Such blindness could easily be said to be an overriding limitation of Australia’s strategic imagination regarding the Indian Ocean. West coast amnesia has clouded Australia’s strategic imagination.

This amnesia has been driven by a combination of geostrategy and the balance of international risk that Australia faced across the Asia-Pacific during the Cold War and post-Cold War eras. The emergence of the Indo-Pacific concept in Australia’s strategic lexicon since 2013, in which Canberra formally recognised, at least in its strategic documents, the interconnectedness of strategic dynamics in the Indian and Pacific oceans, and the rapid expansion of Chinese power across this region, has required that the balance of risk and threat be assessed anew. In the contemporary strategic environment, the perception of the Indian Ocean as a “second sea” must come to an end. The logic that heralded the adoption of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept by Australia in 2013 must be embraced across every policy dimension.

Australia’s changing views on the Indian Ocean

Australian national interests in the Indian Ocean derive from geography. Australia has the longest Indian Ocean coastline in the world and the largest maritime jurisdiction of any Indian Ocean country. Australia has the largest zone of maritime search-and-rescue responsibility in the Ocean, and its exclusive economic zone encompasses 3.88 million square kilometres of Indian Ocean waters.11 The 2023 Defence Strategic Review designated the area from the northeastern Indian Ocean through maritime Southeast Asia as Australia’s primary area of military interest.12 As a result of the maritime character of these areas, “credible naval power” is viewed Australian defence chiefs as an essential enabler Australia’s defence effort.13

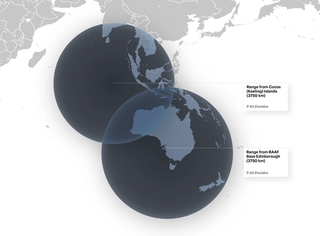

Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands — Australia’s Indian Ocean territories — are tangible demonstrations of Australia’s status as an Indian Ocean power. These two islands are located 1,500 kilometres and 2,000 kilometres respectively from Australia’s northwestern coastline, adjacent to vital Indian Ocean sea lanes.14 Successive rounds of investment by recent governments in expanding infrastructure in these territories will see their operational significance to Australia grow into the future. Enhancements to the airfield at Cocos to enable P-8 maritime surveillance operations are expected to be completed in 2028.15 Financial commitments by the Albanese government in 2023 brought the total investment effort into these territories to A$7 billion.16 With these upgrades, Australia’s operational capability in the Indian Ocean is increasing.

The second key trend animating Australia’s Indian Ocean strategy is the near existential significance of Indian Ocean sealines for Australia’s international trade. As an export dependent free trade state, commentators have been at pains over decades to emphasise Australia’s reliance on the chokepoints and channels of the Indian Ocean for its supply of critical goods, including 90% of its fuel.17 This vulnerability applies to both imports and exports, with 50% of Australian sea freight exports departing from Australia’s western coastline.18 It is estimated that A$130 billion worth of goods move from Australia through the Malacca Strait annually.19 Iron ore shipments from Port Hedland alone are valued at 4% of Australian GDP.20 A recognition of Australia’s trade exposure has long animated Australia’s strategic plans and capability investments. Increasingly, policymakers are alert to the added complexity of Australia’s partners’ dependence on these routes; the four largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) importing countries — Japan, China, South Korea and India — depend upon the passage of Australian LNG exports through Indian Ocean sea lines of communication (SLOC).21

Lastly and crucially, Australia’s security and identity as a responsible regional middle power lies in positive relationships with its neighbours in the Indian Ocean region. Australia’s senior officials consistently assess that a rules-based and stable balance of power in the Indo-Pacific is paramount to Australian interests.22 These recognitions inspire Australian commitment to being a “principled” and “reliable Indian Ocean partner” to countries across the region.23 Australia is a founding member of the Indian Ocean Rim Association — the most (and arguably only) influential multilateral grouping in the region. The 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS) committed to deepening defence relationships with countries in the Indian Ocean and deemed India a “top-tier” security partner for Australia.24 These commitments extend beyond defence, with Australia’s 2023 International Development Policy also built upon the recognition that the Indian Ocean connects Australia to its closest neighbours and demands ambitious education, climate and environmental protection agendas from Australia.25 Since the release of the NDS, strengthening Australia’s relationships with Sri Lanka, the Maldives and Bangladesh is considered a priority for Canberra.

Today, formerly assured realities in the Indian Ocean are subject to new threats. In particular, five trends have emerged in Canberra’s strategic thinking over the past decade that will significantly reshape Australian strategic policy in the region: increasing multipolarity; intensifying India-China strategic competition; the growing risk of simultaneous conflicts across the Indo-Pacific; enduring constraints on India’s leadership; and more obvious US expectations about Australia’s current and future role in the region.

A new reality

Increasing multipolarity

Indian Ocean security expert David Brewster has, for several years, observed growing ‘congestion’ of global and regional powers in the Indian Ocean.26 Declining US relative power, expanded Chinese operations and surging interest from extra-regional partners in engagement in Asia have coalesced in a multipolar order. Resident middle powers in the Indian Ocean are only becoming more relevant; the average age of people in Indian Ocean countries is under 30, compared to 46 in Japan as one example, foreshadowing future economic dynamism that will make states across the region increasingly capable.27 Within the next decade, Indonesia will join India among the world’s five largest economies.28 In many respects, this gives Australia more foreign policy options; India and Japan are increasingly engaged partners in the region, and UK and French interests in the ocean endure. At the same time, China’s economic and defence outreach has, to some extent, displaced US and even Indian pre-eminence in parts of the ocean, introducing new questions for Australia and its partners in how it maintains a favourable strategic balance. A more multipolar region simultaneously increases both the need for and complexity of working with both long-standing and emerging partners.

Intensifying strategic competition

Across the Indo-Pacific, the overwhelming expansion of China’s naval capability has reset the risk calculus of the United States, Australia and their partners. Over the last decade, China has eschewed its habitual continental strategy, emerged decisively as a maritime power and directed its planning towards “fighting (and winning) local wars at distances away from the mainland.”29

From the outset, with the PLAN focused on East Asia and the first, second and third island chains,30 it must be acknowledged that the PRC’s varied military, diplomatic and economic efforts in the Indian Ocean are, by comparison, focused on competing for influence, rather than preparing for looming conflict.

Experts tend to agree that China seeks equality of presence rather than exclusive use of the Indian Ocean.31 Accordingly, China’s strategy for the region is largely development-led, with Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investments as its key (though to an extent retrenching) lever.32 At present, permanent PLAN forces in the Indian Ocean remain limited to eighteen ships. Though this force is larger than the Royal Australian Navy’s major surface combatants, it remains a small ongoing presence relative to the PLAN’s concentrated naval assets in East Asia. Still, instances of grey-zone coercion are intensifying across the Indo-Pacific and are encroaching into the Indian Ocean, where they are focused on intelligence gathering, power projection and the protection of trade routes.33 This includes the circumnavigation of a PLAN taskforce around Australia’s coastline between February and March 2025.34 Recognising these trends, Australia’s defence assets in the Indian Ocean region must be focused on regional engagement and presence operations. Preparing for major power conflict in the Indo-Pacific, driven by the end of Australia’s longstanding strategic warning time of ten years,35 is the planning principle for Australian defence policy. The investment should be focused on increased regional engagement and investments in AUKUS, force posture, infrastructure and the ability of the ADF to operate from the network of bases in the northwest of Australia and its Indian Ocean territories, along with the expansion of the US-Australian enhanced force posture initiatives.

Investment should be focused on increased regional engagement and investments in AUKUS, force posture, infrastructure and the ability of the ADF to operate from the network of bases in the northwest of Australia.

In contrast to other sub-regions of the Indo-Pacific that are centrally confronted with US-China competition, it is the increasingly strained dynamic between India and China that is shaping the Indian Ocean strategic environment. India-China relations deteriorated following the 2020 Ladakh crisis and the subsequent 2022 clashes along the Line of Actual Control. These altercations have intensified underlying India-PRC rivalry across the Indian Ocean region. In the past, Indian officials were somewhat acquiescent, if not hospitable, to Chinese regional policies, including the 2017 establishment of a PRC military base in Djibouti, China’s heavy investment in regional port infrastructure and growing diplomatic footholds. However, a step change in India’s approach to China is now apparent, embodied in Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar’s recent remarks that “at least in the foreseeable future, there will be issues” in China and India’s relationship. This, in turn, creates a new driving dynamic in India and Australia’s relationship.36 Perhaps most significantly, despite enduring reticence in some corners of Delhi about external players’ involvement in Indian Ocean affairs, it has reset India’s comfort level with other, aligned powers, operating in what it views as its maritime backyard.37

China’s first island chain maritime chokepoints

Mounting secondary risks in a regional contingency

Though the Indian Ocean does not garner that same level of immediate strategic concern from Australian policymakers as either Southeast Asia or the South Pacific, Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong has been frank that Indian Ocean countries must confront the potential scenario of strategic competition escalating into conflict in their waters.38 This is largely because, in any security contingency in East Asia, the maintenance of the sea lines of supply for Australia and other Asian countries will be existential. There also remains an essential need for the Indian Ocean to serve as a major force flow corridor for US military forces moving from the Middle East (operated by US CENTCOM) to US forward-deployed bases and logistical staging areas in East Asia (operated by US INDOPACOM). Maintaining a regional strategic balance in the Indian Ocean region, and especially the northeast Indian Ocean, is thus central to Australia’s homeland defence, resilience and economic security in the form of national and indeed global energy supply chains.

Equally, PRC strategies and vulnerabilities in the Indian Ocean will be a key consideration for future policymakers seeking diplomatic and economic levers of engagement. Military planners view the Indian Ocean as a region where the PRC would have exploitable vulnerabilities, given the extent of China’s dependence on seaborne trade.39 In recent years, US experts have remarked that strategists’ operational understanding of how the PRC may operate in the Indian Ocean ahead of a conflict is weaker than their analysis of other regions.40 For instance, the potential for simultaneity — wherein a country looks to apply pressure in various forms on multiple sub-regions in the Indo-Pacific to divert an adversary’s resources and attention — has not been comprehensively understood and prepared for in light of recent tensions.41 US experts agree that it would be logical for the PRC to increase pressure on India’s land border to fracture US partnerships during an East Asian security crisis.42 In anticipation of potential strategic futures in the Indian Ocean, Australian policymakers must reckon with an evolving threat environment.43

The complexity of the changing Indian Ocean dynamics is further magnified by the compounding challenges of non-traditional security threats, emanating primarily from climate change.44 The intensity of climate-related challenges for littoral and island states in the Indian Ocean means that such threats eclipse hard security concerns for many policymakers in the region. They also provide vectors for exploitation for nefarious actors and challenges to traditional security partnerships if they do not evolve to meet them. For Australian policymakers, this both increases the likelihood of simultaneous security challenges and provides a new starting point for security-based engagement with partners across the Indian Ocean region.

Clarifying US expectations

A final reality that will shape Australian policymakers’ calculus is the clear limitations of both US interests and capacity in Indian Ocean waters. This is especially prescient under the second Trump administration. It is clear that the Indo-Pacific remains this administration’s priority region of operations and that the Biden administration’s designation of the PRC as the United States’ ‘pacing’ threat holds constant.45 However, the disaggregation of US strategy under Trump and the rejection of the Biden era policy of integrated deterrence leave partners in the region questioning the extent of US willingness to further substantiate the Indo-Pacific focus that has been developing over the past decade. Questions over US capacity and resolve over the Indo-Pacific have fomented in the first eight months of the second Trump administration with its immediate focus on issues in the Middle East and Europe. The Indian Ocean, where the United States has few material interests at stake, is likely to remain overlooked in favour of higher priority Indo-Pacific subregions such as northeast Asia and the South China Sea.

In some respects, the United States may prove less capable of advancing Australian interests in the Indo-Pacific than Australian policymakers had anticipated. Albanese government officials have been consistent in their view that “the whole [Indo-Pacific] region benefits from US engagement, from their contribution to the region’s strategic balance.”46 The depletion of US soft power is changing the dynamics of strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific (and globally). The dismantling of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) by the Department of Government Efficiency, the imposition of global tariffs, and the over-reliance on hard power, with a strong focus in the northeast Asian subregion of the Indo-Pacific, are limiting the United States’ capacity to contribute to a favourable Indian Ocean balance of power short of conflict. For the remainder of the Trump presidency, Australian policymakers must reckon with the impact of reductions in US investment and reduced appetite for sustained diplomatic overtures in the region.

Increased PRC presence and apparent limitations on India’s capacity have increased strategic challenges for Australia in the Indian Ocean without a corresponding increase in US interests or engagement. Trump’s America First foreign policy may well require a reappraisal of Australian diplomatic and military commitments in the northeast Indian Ocean. In addition, a balance of military operational responsibilities for the northeast Indian Ocean must be, where possible, agreed between the Pentagon, INDOPACOM and the Australian Government. This discussion must be framed in a practical understanding of the limits of Indian maritime power both politically and in terms of military capability, as well as bilateral and minilateral engagement with Indian. In all these discussions, the Australian Government must have practical implications of increased burden sharing by Australia front and centre in order to ensure the appropriate management of Australia’s sovereign interests as well as alliance equities. Recent demands from the current US administration for Australia to increase its defence spending from 2% to 3.5% of GDP increase the importance of these discussions.47 With US policymakers increasingly unified in their push for allies to take greater responsibility for their defence, Australia is expected to make a more concerted, independent contribution to the strategic balance.

Most commentators concur that the Indian Ocean is at present, has long been, and will remain into the future, an economy of force where Washington will allocate a minimum level of defence resources.48 This basic fact requires Australia to pay serious attention to this region as strategic competition intensifies. The concentration of US forces elsewhere in the Indo-Pacific, principally in East Asia and the central Pacific, long predates the second Trump administration. The conception that the Indian Ocean is beyond core US interests is a view that is held by many in the United States on both sides of politics. Unlike Australia and India, the United States does not have an Indian Ocean coastline nor any territorial interests at stake in the region to drive greater diplomatic and military commitments. Despite the renaming of ‘Pacific Command’ in 2018 to ‘Indo-Pacific Command’ and the best intentions of successive US administrations, there remains little basis for the United States to grow its permanent presence in the region beyond the Naval Support Facility at Diego Garcia, even as they have adopted the broader Indo-Pacific as its defining regional strategic concept. This is the consequence of a range of factors, including the immediacy of threats, distance from the mainland United States and the shortage of immediate US interests (including its few trade dependencies in the ocean). As a result, the key strategic imperative for US policymakers is to ensure that the Indian Ocean remains comfortably tertiary relative to demands of higher warfighting priority regions in Asia, the Middle East and the Atlantic.49

The United States will rely on its partners to fulfil key responsibilities, including providing a comprehensive operating picture, protecting SLOCs and disrupting Chinese access.

Consequently, the United States will rely on its partners to fulfil key responsibilities, including providing a comprehensive operating picture, protecting SLOCs and disrupting Chinese access. The recourse for US demands on its regional partners under the Trump administration, with its focus on increased burden sharing, foreshadows more sweeping future expectations. Understanding the current and likely US ask of Australia in both the competition phase and especially in any time of conflict is essential for Australian policymakers to make informed, sovereign decisions about its defence planning and posture now and in the future. Even more importantly, these discussions must be focused around Australia’s strategic interests and ensuring the United States has a comprehensive understanding of these interests and Australia’s sovereign focus of its diplomatic, economic and military power both for immediate effect and the long-term strategic balance.

Ongoing constraints on India’s capacity

Considering the above strategic realities, Australian policymakers must hold realistic expectations about Indian policy options and preferences and explore associated opportunities for partnership. Both Australia and the United States — notwithstanding recent US trade tensions with India over the latter’s purchase of Russian arms and oil and ongoing tariff negotiations — have resoundingly embraced Indian leadership in Indian Ocean affairs.50 India has long presented itself as the primary security provider for the region, embodied in its Neighbourhood First Policy and Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) initiative.51 However, ongoing constraints on India’s capacity are accentuating the demand for Australian engagement and presence in the maritime domain.

India’s military spending relative to GDP has declined for several years in the face of pressure on budget top-lines.52 In addition, pressure on India’s land borders has limited the resources devoted to the development of its maritime capabilities. This trend became apparent after the recent line of control issues with the PRC, which encouraged a reprioritisation of Indian defence spending and seemingly exacerbated shortfalls in India’s naval force projection capabilities in favour of land defence.53 The pressure to continue such actions has only increased with the recent India-Pakistan conflict in May 2025. The Indian Navy gets the smallest budget allocation (17%) of any Indian service.54

Complicated histories with smaller Indian Ocean states have also frustrated Indian engagement; opinion polling shows that India is distrusted by people in Southeast Asia and is criticised for an apparent reticence to assume broader global leadership roles.55 Certainly, playing a supportive or parallel role to India remains imperative to Australian operations in the ocean, but there are increasing opportunities and demands for Australia to leverage its status as an honest broker to ensure the success of India’s maritime defence efforts in the region.

Australian objectives to 2035

Over the next decade, Australia stands to make a key contribution to regional stability, diplomacy and development efforts in the Indian Ocean region. Still, Australia’s Indian Ocean strategy cannot be everything, everywhere, all at once. Defence and diplomatic resources, aid and investment available to the region are limited and finite. Even if the Australian Government decided to significantly increase funding to strengthen its integrated statecraft, the gravitational pull to the South Pacific, as well as Australian interests in both Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia, would likely continue to monopolise attention and available resources. Accordingly, Australian officials must be both ruthless in their prioritisation and focused if they hope to empower partnerships and operations in the Indian Ocean region.

The Australian Government’s pursuit of national objectives begins from the recognition that Australian regional diplomacy must be closely coordinated with both in-region and extra-regional partners, including the United States, Japan, France and the United Kingdom, to maximise its impact. The very foundation of Australia’s approach to strategy across regions is working collaboratively with allies and partners to maintain a regional strategic balance to enable collective deterrence and to help preserve the peace. Recent Australian strategic documents rightly prioritise the northeast Indian Ocean and a western Indian Ocean strategy with a focus on diplomacy and a military strategy based on collective deterrence and denial.56

Australian policymakers must develop a policy approach to the Indian Ocean region through the lens of ‘integrated statecraft’ — that is, to achieve its strategic objectives by coordinating and applying a number of instruments of national power, such as defence, diplomatic and economic assets.57 Consistent with that approach, the remainder of this report is delineated by lines of effort within a nationally integrated Indian Ocean strategy adhering to the following overarching objectives, synthesised from recent Australian strategic documents:

- Contribute to a favourable regional strategic balance alongside allies and partners through continuous diplomatic and military capability, engagement and presence.

- Promote the economic dynamism of Australia’s Indian Ocean partners and unlock the benefits of both sustainable growth and, where possible, greater regional economic integration.

- Positively contribute to the regional strategy balance and respond to instances of grey-zone coercion or aggression against Australia or its partners when they occur and deter the outbreak of conflict in the Indian Ocean.

Objective 1: Diplomatic partnerships and the regional balance of power

The state of play

“Maintaining regional stability” in the Indian Ocean is a matter of national importance for Australia.58 As in all subregions in the Indo-Pacific, Australia aims to contribute to a regional balance alongside its allies and partners. This is obvious in the readouts of Australian officials’ engagements with extra-regional partners — including at the 2024 Australia-US Ministerial, where US and Australian foreign policy and defence principals “reaffirmed their commitment to support Indian Ocean countries and regional architecture to address increasing challenges and advance resilience and prosperity.”59 But it is most apparent in the energetic efforts of Australian diplomats in their bilateral partnerships in the Indian Ocean.

“Maintaining regional stability” in the Indian Ocean is a matter of national importance for Australia.

Over the past 20 years, Australian ties with almost every country in the region have strengthened. As discussed, a centrepiece of Australia’s Indian Ocean strategy is bilateral cooperation with India, which Australia has deemed a “top-tier security partner,” formalised in a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.60 A concerted focus on expanding ties with India has led some commentators to argue that this has caused a relative neglect of other Indian Ocean states.61 Nevertheless, since the release of the 2023 Defence Strategic Review, strengthening bilateral relationships with India, Sri Lanka, the Maldives and Bangladesh has been treated as a priority by the various departments of the Australian Government. The establishment of an embassy in the Maldives, a defence attaché in Bangladesh and the strengthening of the Australian diplomatic mission in India are all significant enhancements of Australia’s regional engagement. The Australian mission in India now rivals the size of Australia’s mission to China. In addition, the Australian Government has in recent years worked to strengthen its trilateral and minilateral configurations relevant to its interests in the Indian Ocean, including advancing a focus on the Indian Ocean in the Quad’s Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief efforts.62

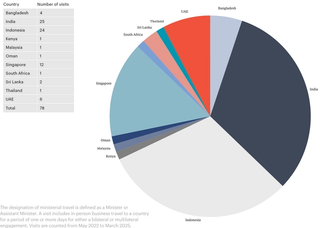

Figure 1. Number of ministerial visits to Indian Ocean states under the Albanese government, 2022-2025

Development assistance is an essential element of Australia’s bilateral outreach and efforts to ensure a stable and prosperous Indian Ocean order. In 2024-5, the Australian Government invested A$130.9 million in bilateral official development assistance in South and Central Asia, discounting global programs.63 It invested an additional A$312.1 million in Indonesia alone.64 Investment in the Indian Ocean region has increased incrementally, but pales in comparison with the A$1.55 billion bilateral development assistance allocated to Pacific countries.65 However, this investment remains a cornerstone of Australia’s engagements in the region. When taking broader programs into account, Australia provides over A$330 million in development assistance and over A$100 million in humanitarian support to South Asia.66

Such offerings provide options to regional partners, whose other choices are often China’s BRI or development partnerships with India, where engagements have struggled under the weight of history and a patchy delivery record on major projects.67 The United States has in the past played a key role in the regional development landscape through its contributions to regional institutionsm, including the Indian Ocean Rim Association and the Bay of Bengal Initiative, as well as several bespoke funding efforts. However, Trump administration policies such as cuts to USAID severely hamper US soft power capabilities and create a lack of clarity on how Washington perceives infrastructure and investment into the region as part of its broader regional strategy. This has meant the collapse of any type of ‘integrated’ approach from the Trump administration to regional balancing and deterrence. Recent funding freezes have left the future of long-standing initiatives in limbo.68 USAID cuts have already had significant effects on regional health infrastructure; one example is the freezing of Stawisha Pwani, a US$47 million program for reproductive health, maternal and child care and HIV/AIDS treatment to four Indian Ocean communities in Kenya, which had collectively been treating 12,000 HIV patients.69

Australian strategists’ concentrated efforts on the eastern Indian Ocean have meant that little has been invested in diplomatic outreach to the west. For example, Australia only has two foreign service officers posted to Mauritius. As a result, Australia relies upon the efforts of extra-regional partners like France and the United Kingdom, who hold a greater stake in that subregion to underwrite development and security outcomes. This approach comes with its hazards, given these extra-regional players’ complicated colonial histories with Indian Ocean communities — the UK-Chagos Islands sovereignty dispute remains a striking example, even as tensions ease.70 Australian experts continue to disagree as to how to right-size Australian commitments beyond the northeastern area of responsibility. Advocates of a stronger Australian focus emphasise Australia’s reliance on tanker transit through sea lanes that stretch across the region, and the significance placed on the west of the ocean by both Delhi and Washington.71

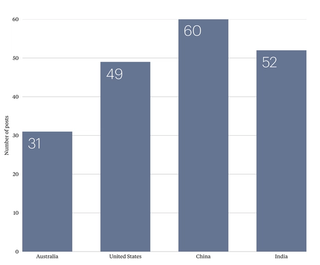

Figure 2a. Number of diplomatic posts in the Indian Ocean by country, 2024

Source: Lowy Institute Global Diplomacy Index, 202472

Australia’s efforts should be put in the context of growing global interest in the Indian Ocean region. Though in recent years the US and Chinese Governments have been particularly focused on competing for influence in the South Pacific, the Indian Ocean has been in no way immune from such efforts. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo made the first cabinet-level visit to the Maldives in 2020, and the Biden administration subsequently appointed Hugo Yue-Ho as the United States’ first Resident Ambassador to the Republic of the Maldives in September 2023.73 While important, these efforts have failed to keep pace with China’s growing diplomatic outreach, as China now has more embassies and overseas missions in the region than any other power and undertakes frequent high-level “neighbourhood diplomacy” at both the leader and senior official levels.74

Among the greatest impediments to Australia’s Indian Ocean outreach is the lack of Indian Ocean regionalism. Commentators concur that Indian Ocean multilateral groupings are ubiquitously weak when compared with counterparts in Europe and Southeast Asia. Australian officials have not been successful in transposing their effective order-building efforts elsewhere in the region, as the Indian Ocean is often described as “complex”, “diverse,” and “fragmented.”75 This century, Australia’s security multilateralism has been limited to its partnerships with India, Japan and the United States.76 Still, Albanese government officials have consistently expressed an interest in “deepening our historical commitment to multilateralism” and “building the institutions of engagement” in the northeast Indian Ocean.77 In the absence of such institutions, diplomats must re-dedicate themselves to resource-intensive bilateral outreach.

Figure 3. Membership in the major multilateral institutions of the Indian Ocean region

For all its shortcomings, the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) remains the most useful inclusive grouping for Australia to collectively engage Indian Ocean partners. The IORA is the only grouping in the region commanding ministerial-level representation, and benefits from the Indian and Bangladeshi Governments’ ongoing support for South Asian regionalism.78 IORA’s impact is constrained by the combination of its expansive membership and consensus-driven model, meaning issues often languish in the face of the diverse perspectives of its members. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), the only regional organisation in South Asia, increasingly has a maritime focus, but it will continually prove ineffectual in the absence of more peaceable relations between India and Pakistan.79

Minilateral groupings increasingly organise and propel Australia’s Indian Ocean efforts. The Quad is the most conspicuous example, though the quadrilateral grouping’s period of dormancy between 2008-2017, its current emphasis on non-hard-security oriented issues and broader geographic focus beyond the Indian Ocean have meant it has not developed as a robust and sustained deterrence to China’s increasing military presence in the region over the last decade. Indeed, India and Australia have played a significant role in channelling the group’s efforts towards regional maritime domain awareness, climate response and HADR efforts in the region. The most tangible example is the expansion of the existing Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) in Gurugram, India, to monitor vessel activities across the ocean and train officers from neighbouring countries.80 Beyond the Quad, periodic efforts continue in other trilateral and minilateral configurations in helping to build what one expert called a “regional consciousness.”81 The Australia-India-Indonesia trilateral is proceeding with senior officials’ meetings,82 and for years, commentators have made the case for more complex cooperation.83 The Australia-India-France trilateral has been similarly elevated. Activities in recent years, including foreign ministerial-level coordination on maritime security and development on the sidelines of the United Nations in 2022 and French contributions to Indian Ocean naval exercises, form the basis for more robust maritime security cooperation on shared Indian Ocean objectives.84 It will be critical that emerging and ongoing minilateral groupings remain clear-eyed in the next decade on the importance of pursuing inclusive groupings that recognise the importance of a variety and integrated approach, including hard-power capabilities, to ensure a favourable strategic balance in the Indian Ocean.

The next ten years

Climate change effects: Presently, littoral and island countries in the Indian Ocean have little resilience against the increasingly acute effects of climate change that they experience. Many Indian Ocean states view this as their single most severe security threat. More than 80% of all global fatalities from tropical cyclones occur in the northern Indian Ocean, despite the region accounting for only 6% of all global cyclone occurrences.85 The impacts of extreme weather events are poised to become more severe, producing major regional human security challenges. Sea level rise of one metre (anticipated by the end of the century) could result in 80% of the Maldives being submerged.86 Consequently, near-term demand will soar for development assistance that improves the resilience of Indian Ocean communities. In South Asia and the Bay of Bengal, there is a reported requirement for approximately US$6.3 trillion (more than A$10 trillion) in climate-adjusted infrastructure investments by 2030.87 Though useful adaptation mechanisms have emerged in recent years, the likely absence of relevant near-term investment under a Trump administration that has disavowed US development efforts related to climate change will frustrate mitigation efforts, as well as parallel efforts in development and economic areas held at risk by the effects of climate change.

Elite capture and democratic backsliding: The tactics that have defined China’s approach to competing for influence in the Pacific Islands are being replicated in the Indian Ocean region. PRC officials have proven capable of exploiting weak democratic governance in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh through elite capture.88 Pakistan’s debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 70% and the World Bank has deemed the country in a “human capital crisis” as wealth has further concentrated in the hands of ruling elites.89 Commentators write that the so-called global democratic recession, wherein over half of the 60 countries that convened elections in 2024 suffered democratic decline or showed increasingly autocratic qualities, is particularly plain in South Asia.90 Though the 2024 Indian election was celebrated by some as ‘holding the line’ for the largest democracy in the region, the regime was downgraded in recent years to a hybrid “electoral autocracy.”91 Elite capture and broader democratic decline across Indian Ocean states make it more challenging for Australian officials to engage on the basis of shared values or in the ways that they would prefer, though of course there is much for Australia to learn from India’s recent ongoing influence to cultivate strategic ties in places such as the Maldives. Such political complexity will intensify both development challenges and geopolitical risk in the coming years.

Collective action problems: The absence of effective regional mechanisms, particularly for security diplomacy, will increasingly pose a challenge for policy coordination in the face of collective action problems. Australia will have to reconcile its ambitions for more sophisticated engagements with regional partners with the limited resourcing and coverage of issues within the prevailing multilateral institutions outlined above. Intensifying strategic competition between India and China, or China and the United States, will increase other Indian Ocean countries’ wariness about multilateral behaviour perceived as alignment. Non-traditional security will remain the best viable avenue for greater coordination in the maritime domain among a set of partners with diverse interests and varied capacities.

Mounting Australian interests in the western Indian Ocean: In light of prevailing resource constraints, Australian officials are right to prioritise diplomatic and security efforts in the Indian Ocean’s northeast in the near term. However, over the next decade, Australian and partners’ interests further ashore are likely to become more pronounced. The surge in the African continent’s population (and in particular, its working age population), protracted conflicts in the Middle East, ongoing dependence on the transit of energy through the ocean, and increased Chinese presence in the region, buoyed by the PRC’s deepening engagement with Mauritius, Seychelles, Comoros and Madagascar, will increase the onus on Australia to expand its investment and attention beyond its near region.

Indian diaspora: The Australian Bureau of Statistics projected that Australia’s Indian-born population would grow to 1.07 million by 2035.92 Discounting the pandemic period, India has been Australia’s largest source of net overseas migration since 2018,93 and Indian-born migrants have been, for many years, the biggest pool of those seeking Australian citizenship.94 This growing Indian diaspora community in Australia is seen as a ‘force multiplier’ for Australia’s strategic efforts in the region.95 This increasingly powerful voting bloc will exercise significant influence over Australian policy going forward and underline perceptions of shared values in Australia’s bilateral relationship with India. This may drive both greater trust in India and more comprehensive interest in the Indian Ocean region. Taken together, the Australian Government should pursue its objective of achieving a favourable strategic balance in the Indian Ocean by considering the following:

Recommendations

- Post election, the most recent (2025-) Albanese government has appointed Assistant Foreign Minister Tim Watts as Australia’s first Indian Ocean Envoy, in an indication of the growing importance of the region to the Australian Government. The next stage of ministerial engagement should entail the Prime Minister appointing an Assistant Minister for the Indian Ocean as a counterpart to the Minister for the Pacific. This role would underwrite continued interest in the region at the official level, demonstrate prioritisation to the region and provide a clear pathway for senior-level engagement to official counterparts across the region; by encompassing the Indian Ocean, this minister will also have a focus on key Southeast Asia maritime states such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand.

- Along with broadening bilateral engagement with key Indian Ocean states, Australia’s diplomats should prioritise substantiating limited minilateral configurations in the Indian Ocean — namely, the Australia-India-United States trilateral, the India-Australia-Indonesia trilateral and the India-Australia-France trilateral. Minilateral groupings hold greater prospect for collective action on maritime security issues than the existing multilateral institutions in the region and spare the resources of endeavouring to configure ambitious new configurations that may be ineffectual. Importantly, minilaterals that do not include the United States provide options to Australia and non-aligned regional partners. Though minilateral cooperation has tended to proceed ad hoc or with a strict focus on blue economy or marine pollution issues, as an example, they are worthy efforts in growing the connectivity of Indian Ocean states and may develop a greater security focus in the future. Though Australian policymakers must set reasonable expectations around the impact of larger multilateralism, officials should not arbitrarily close off future opportunities for groupings that could empower sub-regional security in the northern Indian Ocean.

- The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade should continually re-evaluate its development priorities to ensure they can fill gaps left by the disabling of USAID and reductions in UK development funding over the decade in the Indian Ocean. India continues to play a leading role in delivering high-impact community development projects, but larger, strategic investments by Australia make a fundamental input and take advantage of Australia’s reputation as a benign, honest broker in the region.

- The Australian Government should further invest in fully equipped posts across the Indian Ocean region, noting that its relations with small Indian Ocean states are primarily Ambassador-led. The scale of activities that emerge from the US post in India provides an instructive example of the impact of post-level outreach. While Australia’s foreign policy is more interagency focused, enhancing post capabilities and autonomy provides for opportunities to exponentially expand relations based on Canberra’s mission strategy and intent. Expanded Australian diplomatic posts should both inform and accommodate more regular senior official travel from Australian ministers.

The Australian Government should further invest in fully equipped posts across the Indian Ocean region.

- Even in the absence of major reallocations of Australian investment or military assets, Australia should seek greater planning connections with extra-regional partners on both diplomatic and non-traditional security objectives in the western Indian Ocean. Transparent coordination should occur with France and the United Kingdom on the division of labour in the western Indian Ocean to avoid unnecessary duplication of efforts when respective national resources are strained. Australian officials must increasingly consider limited contributions to partners’ non-traditional maritime security and development programs where Australian inputs could maximise impact.

Objective 2: Promoting sustainable development and economic integration

The state of play

Australia is a significant trade presence in the Indian Ocean. A 2024 ASPI study estimated that approximately 65% of Australia’s maritime exports and 40% of its imports travel through Indonesia’s archipelagic sea lanes. Australia’s bulk commodity exports transiting these routes account for 29% of global bulk shipping.96 Indian Ocean trade routes remain of particular national and global significance, as previously discussed, for the transit of liquid energy in particular.97

India, Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia are among the ten countries trading the highest value through sea freight with Australia. Though typically conceptualised as strictly Southeast Asian powers, the passage of trade through Indian Ocean routes underscores the connected nature of these Indo-Pacific sub-regions. In terms of the routes of greatest interest to Australia, the Lombok Strait is critical to export iron ore from the Australian coast to North Asia, where the Malacca Strait is used by most container and vehicle ships coming to Australia from Europe. It should be acknowledged that, when it comes to economic connectivity, Australia’s ties in the Indian Ocean pale in comparison to those in Southeast Asia. Australia’s free trade agreements with countries in the Ocean’s rim are almost exclusively with Southeast Asian partners (including Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia).

Figure 4. Australian two-way trade partners (A$ millions)

In contrast, since 2005, China has been the most significant import market for most Indian Ocean states. China has the highest cumulative trade volume with countries in the region (US$900 billion), followed by the United States (US$361 billion).98 Traditional regional partners, such as Australia and France, rank much lower. China has significantly outperformed other major trading partners in the Indian Ocean since 2005. Equally, as previously mentioned, China’s Indian Ocean routes represent a considerable vulnerability. Of the ten countries that supply 75% of China’s energy, nine rely upon Indian Ocean transit routes.99

The Indian Ocean is remarkable for its low intra-regional trade. Intra-regional trade represents 5% of total trade in South Asia, compared with 25% in ASEAN.100 In previous years, the World Bank has aggregated this economic activity at just US$23 billion (A$36.5 billion), far below its estimated value of US$67 billion (more than A$106 billion).101 Experts attribute the region’s relatively languid trade ecosystem to poor multilateralisation, insufficient port infrastructure (though positive moves have been made in this direction in recent years), limited natural resources, and intensifying climate change-related threats. At present, no port in the northeast Indian Ocean is among the top ten in the world for container handling volume, despite the tremendous volume of shipping traffic passing through these ports (up to 30% of global traffic).102

Figure 5. Australian merchandise exports to Indian Ocean rim countries (2021-2023)

Across the region, significant development disparities endure, in part due to this absence of trade-led growth. Foreign direct investment and population growth are propelling sustainable growth for island states.103 The western Indian Ocean is experiencing rapid growth in large-scale development, though questions endure about its sustainability.104

Despite the aforementioned challenges impacting Indian Ocean economic integration, Canberra is increasingly seeking to deepen its understanding of South Asian markets and explore greater economic engagement.105 Economic trends across the broader Indian Ocean will inevitably shape Australian interests — directly and indirectly — and will have an impact on Australia and those of its partners in Southeast Asia and the wider Indo-Pacific. As such, much like their strategic dimensions, economic developments in the Indian Ocean cannot be viewed in isolation from those in Asia and the Pacific. These are interconnected arenas in which Australian engagement is essential to sustaining both economic vitality and broader stability across the Indo-Pacific, and which the Australian Government should remain clear-eyed about the importance of addressing over the coming decade.

The next ten years

Blue economy — sustainable use of the ocean for economic growth, environmental protection and improved livelihoods: Maintaining the upward trajectory of Indian Ocean states’ growth will rely upon small states’ abilities to extract maximum benefits from the blue economy. Sustainable growth has long been a collective priority for Indian Ocean states, institutionalised in the IORA Jakarta Declaration on the Blue Economy in 2017.106 Littoral and island states rely extensively on marine resources for their food security and key industries. In the western Indian Ocean, fishing provides food security and employment for almost 60 million people.107 Australian officials are alert that the Indian Ocean partners’ capacity to take advantage of their natural environment is threatened by both illegal and unregulated fishing, as well as the encroaching impacts of climate change.108 Indian Ocean economies stand to be especially exposed to the threats of manmade climate change; the ocean has accounted for more than 30% of temperature increases in the world’s oceans in the last 20 years.109

Collisions and congestion: Due to the volume of ships transiting Indian Ocean routes, key sea lanes have long been prone to congestion and collision. The frequency of these disruptions is expected to increase exponentially as shipping traffic grows over the next decade, leading the Malacca Strait, for example, to exceed its capacity by then.110 Indeed, this trend is witnessing a 2% increase in traffic in the Malacca Strait each year.111 Experts warn that blockages or traffic jams of narrow Indian Ocean chokepoints will require ships carrying critical cargo to take long detours, which larger ships and tankers may find impossible to navigate.112 Consequently, multilateral efforts to improve the safety of vehicle traffic and a national effort to improve supply chain resilience to adapt to future disruptions must be simultaneously prioritised by the Australian Government.

Piracy: Following a long period of abatement enabled by effective international counter-piracy efforts from 2011 onwards, piracy has again begun to increase across the Indian Ocean. Somali pirates have reportedly exploited the vacuum left by a reallocation of US, UK and partner forces from the Indian Ocean to adjacent waters in the Red Sea in light of the recent eruption of conflicts in the Middle East.113 Five confirmed hijackings by pirates have occurred since late 2023, including a Maltese-flagged bulk carrier MV Ruen.114 Where currently Australia has a lesser interest in western Indian Ocean piracy than other Quad partners, it will increasingly represent a point of concern into the future.115 As conflicts in the Middle East persist, encouraging non-state actors to exploit resulting vulnerabilities, Australian counter-piracy efforts must be redoubled and extended beyond regions of immediate concern.

Recommendations

- The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade should supplement its 2018 “India Economic Strategy to 2035”116 with an Economic Strategy for the Indian Ocean to 2035. This larger document, similar in form and style to the Economic Strategy for Southeast Asia, should set out a region-encompassing agenda of trade and investment priorities that considers the future economic potential of smaller Indian Ocean states. Such a strategy would reduce the India-centrality typical of Australian policy for the region.

- The Australian Government should coordinate with the private sector to facilitate investments in regional port infrastructure that would advance small states’ economic growth and encourage intra-regional trade.117 Priority areas may include decarbonisation (where Australia is already a global leader), digitalisation and capacity building of operators.

- Australia should expand its work with local governments and organisations to grow their capacities to counter threats in the Blue Economy, including illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and piracy. This would involve increasing information sharing to improve island countries’ visibility over their maritime environment.

- Australian senior officials should advance the economic integration of Indian Ocean states by encouraging greater regional multilateralism where possible, including through the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI).

Objective 3: Deterring conflict and responding to coercion in the Indian Ocean region

State of play

The drivers for geostrategic change in the Indian Ocean are beyond Australia’s control. They are a measure of geoeconomics, geopolitics and Australia’s continued maritime dependencies. It is, however, firmly in Australian policymakers’ grasp as to how they shape and engage with the region in response to new challenges. Intensifying geostrategic challenges demand that Australia embrace a more holistic approach to its strategic geography. Canberra must unite its defence policy ambitions, merging its Pacific Ocean interests with a renewed focus on the changing balance of power in the Indian Ocean. Australia’s defence policy must respond to mounting Indian Ocean interests, informed by the changing strategic balance in the ocean, the balance of risk to Australia’s trade and energy dependencies, the growing expansion of Chinese military presence in the Indian Ocean, and northwestern Australia’s proximity to Chinese military power.

Intensifying geostrategic challenges demand that Australia embrace a more holistic approach to its strategic geography.

The 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) reframed the Australian Government’s understanding of its strategic geography. The DSR formally shifted Australia’s defence policy away from a posture focused on managing escalated low-level threats to a focus on strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific and the risk of major war in the region. It reaffirmed the end of ten years of ‘strategic warning time’ outlined in the 2020 Defence Strategic Update (DSU).118 That is, from the mid-1970s to 2020, Australian defence policies were based on an understanding that the threat of a high-intensity conflict would become credible over a longer term, after the strategic environment had evidently undergone an extended period of deterioration.119 Another important feature of the DSR for Australia’s strategic policy was, as scholar Stephan Frühling noted, the need for ADF to be “much more focused force structure based on net assessment, a strategy of denial, the risks inherent in the different levels of conflict, and realistic scenarios agreed to by the Government.”120

The net assessment and the rejection of the ADF as a ‘balanced force’ are central to the DSR. As Frühling goes on, “net assessment as an analytical method has many applications, but the context makes clear that the review wants the ADF to be designed to meet one, extant, actual, clear and present threat — from China.”121 Net assessment is another way of saying threat-based planning, but where there is a singular, overriding, and known threat.122 This was also underlined to the Australian public in 2025 when the Chief of Defence Force, Admiral David Johnston, noted that “the nation needs to be prepared for the possibility of launching combat operations from its own soil, which he calls a ‘very different’ way of thinking to Australia’s approach since WWII.”123

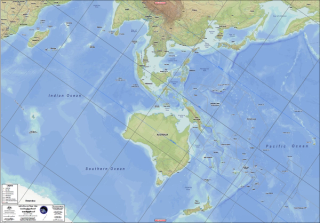

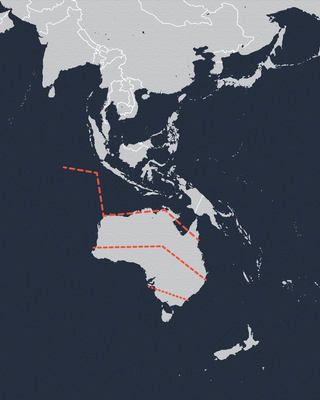

Australia-India-Land Bridge Map

Such an approach demands a reimagination of Australia’s defence policy based on the proximity to the threat and the country’s dependencies and vulnerabilities. The DSR’s defining geographical reference point is the Australia-India-Landbridge map.124 This map represents the alignment of northwest Western Australia and the offshore territories of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Christmas Island to the northwest Indian Ocean. This area is where Australia’s geography is closest to the intersection of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

The unique orientation of this map provides the geography of Australia in the Indo-Pacific relative to the risk emanating from China. It clearly articulates the importance of Australia’s northwest and its Indian Ocean territories relative to the geographical distance to China, the South China Sea, and maritime Southeast Asia. Most significantly, it highlights the long sea line of supply that extends across the Indian Ocean for energy security and into the key maritime choke points in Southeast Asia.

This map reorients Australia’s strategic thinking and elevates the northeast Indian Ocean as an area of paramount concern, highlighting the opportunities and vulnerabilities of Australia’s strategic geography on its Indian Ocean coastline. It also reminds strategists that the distances in the Indo-Pacific, even within its subregions, are vast.125

Reconceiving Australia’s geography is central to understanding the drivers and interests of Australian defence policy and its role in contributing to a regional strategic balance. If Australia cannot conceive its geography appropriately, policymakers in Canberra will not be able to effectively allocate resources as required to maintain a favourable regional strategic balance. Such posturing is central to enacting Australia’s denial strategy, both as part of a regional collective deterrence effort and the ADF’s military strategy of denial.126

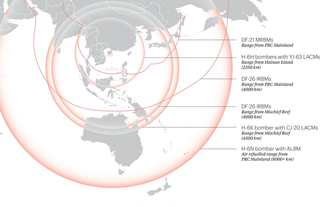

The other defining trend of Australia’s Indian Ocean operations is the shifting strategic balance and growing risks for Australia. This was highlighted in a recent Lowy Institute report outlining the PRC’s growing military capabilities in the South China Sea. The report included a map that represents the effective reach of PRC military power.127 This map (see below) serves to highlight the risks that Australia may face and the change in regional strategic balance not just in Asia but in the eastern Indian Ocean as well. As the report noted, “China’s recent military development constitutes the greatest expansion of maritime and aerospace power in generations and is most obviously seen in its expanding long-range missile force, bomber force, and modernising blue-water navy.”128

The increasing reach of China’s strike capabilities

The map highlights the geographical proximity of northwestern Australia and Australia’s Indian Ocean territories to the maritime choke points at the hinge of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, the South China Sea, the Philippine Sea, and onwards to Taiwan and East Asia. It also highlights not just the criticality of this region but also the importance of the ADF’s network of northern bases for the defence of the area (and for force projection into the region), as well as the genuine risk of cruise and ballistic missile attacks to northwestern Australia in the event of a major regional contingency.

The risks outlined in the DSR were incorporated into formal government strategy with the release of the 2024 NDS. The NDS sharpens the official language vis-à-vis China used in the DSR. The NDS notes that the “risk of a crisis or conflict in the Taiwan Strait is increasing, as well as at other flashpoints…[including] increasing competition for access and influence across the Indian Ocean, including efforts to secure dominance over sea lanes and strategic ports.”129

In addition to the focus on collective deterrence to achieve a regional strategic balance, the 2024 NDS commits the ADF to a strategy of denial focused on a primary area of military interest, including the northeast Indian Ocean. As part of this strategic blueprint, the Australian Department of Defence (hereafter, the Department of Defence) is committed to:

regularising the ADF’s presence, including increasing deployments, training and exercises with Sri Lanka, the Maldives and Bangladesh; and strengthening Australia’s defence cooperation with Indian Ocean region countries through regional maritime domain awareness, growing defence industry engagement and increasing education and training cooperation.130

The strategic risks being driven by expanded PRC capabilities in the broader Indo-Pacific mean Australia’s strategic policy community must develop a deeper understanding of the integrated relationship between the role of the Indian Ocean in the defence of Australia, not just in terms of geographic proximity to the Australian continent but also relative to East Asia’s flashpoints and potential contingencies, to the sea lines of communication, to energy security, to the regional strategic balance in the India Ocean and the PRC’s ambitions in the region.

Rising PRC presence in the Indian Ocean

As China’s power grows, it will want to expand its presence into the Indian Ocean. A key driver of the PRC’s growth and economic stability is energy, with two-thirds of global energy shipments travelling through the Indian Ocean, and 80% of China’s stores being provided through these shipments.131 In addition, the Indian Ocean matters to China because of Beijing’s substantial investment in and energy dependence on Africa and the Middle East.132 On current trajectories, surges in PRC presence will shift the regional strategic balance.133

A search for new markets and the expansion of its global power into China’s second-nearest ocean has seen the creation of a network of PRC commercial and military hubs in the region, or what some analysts have referred to as the ‘string of pearls’.134 From 2015, the PRC has invested A$1 billion in Madagascar for the construction of its Tamatave Deepwater Port Project. It provided Tanzania A$10 billion in investment — the largest recipient of Chinese investment into its port infrastructure — in return for access to 900 kilometres of its coastline and attempted to establish port facilities across the region.135 The dual use of these facilities, including their military dimensions, is clear.136 As an Asia Society report has noted:

Chinese laws mandate that even overseas infrastructure be designed to meet military standards. These laws authorize the military to commandeer ships, facilities, and other assets of Chinese-owned companies. China’s push for civil-military integration builds-in dual-use commercial and military functionality in BRI infrastructure and associated technologies.137

Chinese energy dependency on the Indian Ocean has created what is known as its “Malacca dilemma” — “the risk that its adversaries could close off the Strait of Malacca and thereby cut off its [China’s] vital energy supplies.”138 This is being offset by BRI projects to direct overland pipelines, to connect the Kra Canal through Thailand to the Gulf of Thailand and onto the Andaman Sea. The other component of this strategy, as previously acknowledged, is to build commercial and military infrastructure across Myanmar, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives.139 These ‘strategic strongpoints’ close to maritime chokepoints and critical sea lanes can support the Chinese military’s logistics network and improve its ability to operate further from home.140 Indeed, China’s first overseas military base was established in Djibouti in 2017, and it signed a 99-year lease for the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka beginning in 2017. In 2016, China commenced construction of a deep-sea port project in Myanmar.

Port access is critical to China’s ambitions. The PRC is a leader in the global transportation industry and owns or operates 96 ports in 53 countries.141 These commercial ports have direct strategic importance, with many already providing “dual-use capabilities to the People’s Liberation Army during peacetime, establishing logistics and intelligence networks that materially enable China to project power into critical regions worldwide.”142 PLAN presence operations through port calls and refuelling stops, and diplomatic engagements have occurred in one-third of PRC companies’ overseas ports. PLAN warships have used nine of these ports for “significant repairs or maintenance.”143 These port calls and maintenance work have all occurred since 2017 and are focused so far “only on the route from China across the Indian Ocean.”144

Case Study: Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port

Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka offers an interesting case study in Chinese port development in the Indian Ocean.145 Hambantota has proven to be neither commercially viable nor a market-based investment, as it has seen only a fraction of the port traffic that would justify such an investment. In fact, before the port had been handed over to China as part of a 99-year lease in December 2017, traffic has generally declined, with only 175 cargo vessels arriving that year.146 In 2024, Beijing, with an 80% ownership share of the port, pressured the Sri Lankan Government to offer Hambantota as a forward base for Chinese maritime surveillance vessels, including the massive Yuan Wang 5 which has been conducted undersea hydraulic mapping in the area — most likely related to undersea warfare requirements — and was deployed to the region in advance of PLA missile tests in 2022 with its visible array of signals intelligence equipment.147