Overview and executive summary

Under defence policy planning guidance, the Albanese government has adopted a two-year cycle of review for the delivery of a National Defence Strategy and an Integrated Investment Plan. This is designed to allow the government of the day to reassess strategic and investment priorities informed by an assessment of Australia’s strategic circumstances and its defence capability needs. This provides a clear policy framework to assess and fill any defence capability gaps that arise.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has repeatedly indicated that the Australian Government will fund capability gaps in the Defence portfolio. In response to demands from Australia’s US ally to increase defence spending to 3.5% of GDP, the Prime Minister noted his approach to defence policy: “what you should do in defence is decide what you need, your capability, and then provide for it. That’s what my government’s doing. Investing in our capability and investing in our relationships.”1

At the National Press Club in June 2025, Prime Minister Albanese noted in relation to defence spending that: “What do we need? What is the capability we need to keep us safe? Our capability will always be supported, any submissions, by myself as Prime Minister. Because our first order is to keep us safe and we do that through capability… We will always provide for capability that’s needed.”2

It is clear from the Prime Minister’s statement that an assessment of capability for the Defence of Australia is the foundation of his government’s approach to Defence funding, not arbitrary percentages of GDP. The Albanese government is committed to assessing defence spending through the defence policy planning process, culminating in a new National Defence Strategy in 2026.

Prime Minister Albanese also noted the focus for this process is identifying any potential capability gaps and filling them. In response to a follow-up question from Sky News journalist Andrew Clennell during the National Press Club address in June 2025, the Prime Minister noted, “I’ve made it very clear, we will support the capability that Australia needs. I noticed in your question you haven’t put forward one thing — one thing — that we should be investing in that we’re not investing in.”3

For the Australian Defence Force, the lack of effective ground-based air defence and an Integrated Air and Missile Defence system represents the most critical gap in the achievement of Australia’s strategic goals.

The pathway for additional investment is therefore well-defined: the identification of a clear capability need for the Australian Defence Force as part of National Defence. In reviewing current Defence investment priorities and strategic guidance, there is one very obvious capability gap that is currently not prioritised and critical to defence capability and the nation’s defence strategy: Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD).

IAMD is a critical part of effective deterrence and essential for the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to carry out a military strategy of denial as directed by the 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) and endorsed by the 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS). Lessons from contemporary conflicts have identified that ground-based air defence (GBAD) is essential to an effective IAMD system.

For the ADF, the lack of effective ground-based air defence and an IAMD system represents the most critical gap in the achievement of Australia’s strategic goals.

In 2023, the DSR stated that the ADF was ‘not fit for purpose’ for the strategic environment that had evolved in the Indo-Pacific over the preceding decade. IAMD was specifically singled out by the DSR as an area that was lacking in ADF capability. It noted that “Defence must deliver a layered integrated air and missile defence (IAMD) operational capability urgently” and that “missile defence capabilities should be accelerated.” The Independent Leads of the DSR noted that Defence had not prioritised this capability appropriately:4

[W]e are not supportive of the relative priority that the program was given. The program is not structured to deliver a minimum viable capability in the shortest period of time but is pursuing a long-term near perfect solution at an unaffordable cost.

When the Australian Government announced its implementation plan for the DSR, this sense of urgency for IAMD was not reflected. However, six priority areas were identified for implementation: the AUKUS submarine program; long-range strike and missile manufacture; ADF’s ability to operate from Australia’s northern bases; workforce development; partnership with industry; and deepening diplomatic and defence partnerships.5

The continued deterioration of the Indo-Pacific strategic environment and the lessons from the conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East since the DSR was released have made it clear that IAMD needs to be reassessed. In the implementation plan for the 2024 NDS and Integrated Investment Plan (IIP), it was clear that IAMD has not been acted on with the priority allocated to it in the 2023 DSR or as suggested in previous defence strategic guidance going back to 2016. In addition, the focus of the IAMD investment program within the IIP was not restructured to focus on missile defence as the DSR recommended.

Under the 2024 NDS and IIP, the current investment pipeline massively favours sensors, integration and command and control at the expense of active missile defence. At the same time, it pushes the funding for these capabilities into the latter part of the decade, where funding is only aspirational.

This means that the ADF has a growing capability gap. A gap that contemporary conflicts have highlighted is critical to homeland defence and force protection.

The centrality of IAMD to Australia’s evolving strategic landscape was highlighted by the Chief of Defence Force (CDF), Admiral David Johnston, in June 2025 when he acknowledged that the nation needs to be prepared for the possibility of prosecuting combat operations from its own soil. He described this as a “very different” approach to Australia’s military operations since the Second World War.

To provide a platform for the conduct of operations from Australia’s shores a robust ground-based air defence (GBAD) capability is the central core of homeland defence against air and missile threats. It is the cornerstone of a layered defensive system, providing a level of coverage and persistence that cannot be matched by air or naval capabilities.

A robust GBAD capability allows for the ADF to concentrate its air and naval assets to conduct counter-air and strike missions deep into the battle space, in support of air and missile defence or to achieve broader tactical, operational and strategic objectives. This is essential to providing depth to the defence of the Australian continent and the ADF’s strategically important northern base network.

Australia’s current GBAD capabilities are inadequate to meet contemporary threats and to provide for homeland defence or force protection to deployed forces. It lacks the scope and scale to support a theatre-wide IAMD system. This means that Australia’s approach to IAMD is less than the sum of its parts, as many of the parts themselves are missing.

In line with the DSR recommendations, the next iteration of the NDS and IIP Australia must expand in-service, off-the-shelf capability options to deliver an effective and layered system of GBAD capability to enable the ADF to field a robust IAMD system. This must include C-UAS capabilities, cruise missile defence, intermediate-range ballistic missile and hypersonic missile defence.

To deliver this system, the Australian Government must prioritise capability investment in key areas. This report provides both the strategic rationale for this investment in the 2026 National Defence Strategy and a roadmap towards the fastest and most cost-effective investments for a robust ground-based air and missile defence system — the missing element in the establishment of an effective ADF Integrated Air and Missile Defence capability.

Policy recommendations

- Prioritise IAMD and especially GBAD in the 2026 National Defence Strategy and Integrated Investment Plan.

- Accelerate and integrate the ADF’s GBAD capabilities in a tiered manner to provide practical solutions from counter-UAS capabilities and short-range air defence (SHORAD) through to mid-tier and ballistic missile defence.

- Expand the Army’s air defence capabilities by providing the requisite workforce and funding for GBAD. This should include the expansion of the number of air defence regiments in the Army and the integration of Army Reserve force soldiers and subunits into the Army’s GBAD capabilities.

- Prioritise in-service, off-the-shelf rapid delivery GBAD capabilities and investigate medium-term adaptive solutions.

- To ensure that the system is more than a sum of its parts and that it is integrated together in a theatre-wide IAMD system, Defence must fund effective integration as a priority effort.

Governance, IAMD architecture and program development

- Provide a new model of governance for IAMD, which ensures effective integration as a theatre system of systems.

- Transfer IAMD architecture design and integration to Joint Capabilities Group with requisite staff and funding to develop a short-term, medium-term and long-term program design

- Allocate necessary resources to the Vice Chief of Defence Group, including appropriate technical staff, to provide for effective IAMD integration, including systems assurance.

- Transfer program development for GBAD for mid-tier and ballistic missile defence to the Army.

Mid-tier Air Defence

- Rapidly acquire the extended range (ER) AMRAAM missile for the NASAMS system.

- Rapidly acquire additional NASAMS Fire Units, optimised for the use of the AMRAAM-ER missile — this includes CEA radars and Canister Launchers.

- Develop a mobile launcher for AMRAAM-ER based on the in-service Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicle, matching the current Hawkeye mobile launcher system for standard AMRAAM.

- Investigate the adoption of the SkyCeptor missile into the NASAMS system.

Air and Ballistic Missile Defence

- Rapidly acquire the US Patriot system with PAC-2, PAC-3 CRI and PAC-3 MSE missiles for the Australian Army to deliver an off-the-shelf proven BMD system.

- As a mid-term adaptive solution:

- Pursue the adoption of the Australian CEA Radar into the Patriot system, including the certification of the kill chain for PAC-2 and PAC-3 missiles. This will enhance the system’s performance and create an export market opportunity for Australia’s industry.

- Pursue the integration of Patriot Launchers and missiles into the Australian NASAMS system’s Fire Distribution Centres (FDC). This will improve systems integration, enable workforce reduction, and allow the deployment of mixed batteries of NASAMS with Sidewinder, AMRAAM, AMRAAM-ER missiles with Patriot missiles and launchers.

- Investigate the adoption of the next-generation US Army autonomous launching system.

Short and Very Short-Range Air Defence (SHORAD and VSHORAD)

- Acquire AIM-9x Missiles for Army’s NASAMS system as the current system is ‘fitted for’ but not ‘with’ these missiles.

- Introduce Skyranger air defence turrets onto the Australian-built Boxer Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles to provide a mobile air defence solution to the Army’s mechanised combined arms teams and for VSHORAD missions.

- Acquire the shoulder-launched Stringer missile system to provide for a soldier-portable air defence solution (MANPAD).

- Develop a highly mobile SHORAD system based on the Stinger missile paired with a remote weapons station for the Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicle, replicating the US Army Avenger System and/or M-SHORAD Striker vehicle system.

GWEO

Building on the Statement of Intent on Integrated Air and Missile Defense signed at the 2024 AUSMIN meeting, Australia should:

- Expand Australia’s GWEO mission to include the production of surface-to-air missiles through key componentry and eventually whole missiles.

- Improve local and regional missile readiness and preparedness for the ADF, US Forces and regional partners by developing Australia as a regional hub for the maintenance and sustainability of surface-to-air missiles through the maintenance of missile and the certification in Australia of test and evaluation capabilities for AIM-120 AMRAAM family of missiles (used by the RAAF and the Army’s NASAMS capability) and the Patriot PAC-2 and PAC-3 missiles.

- Identify with the US government and industry key supply chain blockages in areas such as seekers, warheads, and/or guidance systems for either the AIM-120 or the PAC-3 missile, for Australian companies to complement US production.

- Investigate, in line with Japan, the assembly of PAC-3 missiles in Australia.

- Develop a longer-term plan to produce either the AIM-120 AMRAAM family of missiles and/or the PAC-3 missile in Australia.

ASCA and DSTG

- Prioritise ASCA Mission and DSTG R&D programs on:

- the development of laser and microwave systems.

- development of a cost-effective and rapidly replenishable missile interceptor.

- Investigate priority cooperation areas in AUKUS pillar II on the application of:

- IAMD integration.

- Artificial intelligence for IAMD, including analysing and interpreting track data, and target identification for missile intercept allocation.

Introduction

The need to defend the homeland

In June 2025, the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) for Australia, Admiral David Johnston, acknowledged that the nation needs to be prepared for the possibility of launching combat operations from its own soil, which he described as a “very different” approach to Australia’s military operations since the Second World War.6 This is an acknowledgment that in a major conflict or contingency, war may very well come to Australia’s shores.

This assessment responds to the rapidly changing strategic circumstances that Australia, the Indo-Pacific and the world are experiencing. As put by Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles, the nation is facing its “most challenging strategic environment since the Second World War.”7

These circumstances are a result of a range of changes to Australia’s strategic environment. In the period following the Second World War, Australia benefited from the United States’ provision of uncontested maritime supremacy in Asia and a relatively benign Indian Ocean region. Since 2013, the strategic circumstances in Australia’s region have undergone rapid change. The United States has entered a period of relative decline as other major powers, such as China and India, continue to rise in global economic importance. As such, the era of US hegemony has ended, replaced by a more multipolar Indo-Pacific. Internationally, the revisionist powers of Iran, Russia, China and North Korea have used this changing power dynamic to challenge the rules-based international order under which Australia has flourished.

War has engulfed Europe with Russia’s illegal and immoral invasion of Ukraine. Conflict in the Middle East has erupted on multiple fronts, including between Israel and Iran, and China continues to use military force and economic sanctions to coerce its neighbours to reshape the Indo-Pacific in its own image. China’s military expansion in recent decades is unprecedented in modern times. As Richard Marles has noted, “What we have seen from China is the single biggest increase in military capability and build-up in conventional sense by any country since the end of the Second World War,”8 “without strategic reassurance.”9 This also includes the largest nuclear buildup since the early days of the Cold War.10 China now fields the largest military in the world, including the largest navy by ship count, with over 400 vessels, and continues to expand its long-range strike options beyond the Indo-Pacific.

Defence of the homeland is now a significant priority for the Australian Defence Force and the nation.

In another significant development in mid-2025, Richard Marles acknowledged that “China’s ever expanding war machine poses the greatest risk to Australia and the region’s stability.”11 He also publicly acknowledged that “Australia’s continental geography would become an issue in the event of a US-China conflict.”12

Defence of the homeland is now a significant priority for the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and the nation.

The last time this was a serious consideration was during the Second World War, when northern Australia was a major target, which saw at least 111 air raids between February 1942 and November 1943. The first and most significant of these raids was on 19 February 1942, when 188 aircraft bombed Darwin across two raids, the first by carrier aircraft at 9:57 am and the second by land-based bombers at 10:40 am. This combined raid dropped “115,000 kilograms of bombs…two and a half times the number of bombs and 83 per cent of the tonnage dropped on Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941.”13 It was followed up with air raids during 1942 and 1943 across northern Australia, including Exmouth Gulf, Broome, Port Hedland, Wyndham, Derby, Horn Island and Townsville, and the submarine raids on Sydney and Newcastle in June 1942.

A modern-day threat to Australia is not unrealistic. China’s continued use of military coercion in the region to achieve its political objectives represents, as the Australian Government has noted, a grave risk to the peace and stability of the Indo-Pacific. Military threats are based on a combination of capability [military hardware and platforms] plus political intent.14 Capability development is a very long-term, more difficult area of this equation for nations to develop. Intent is a political mechanism that relies on a combination of capability plus opportunity.

The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) military capabilities are massively expanding and extend to the ability to conduct missile and air attacks against the northern region of Australia. While this is not to say Australia faces a certain threat, the nation’s defence policy and planning rely on a “coherent prioritization of the strategic risks a country perceives in its environment.”15 With the risk from the unprecedented expansion of PRC military capabilities being recognised by the Australian Government, the focus for the nation’s defence planning must be on the development of capabilities to defend the nation and its interests. This approach allows the Australian Government to focus defence policy on building the requisite military capability to reduce strategic risk, meaning that there is “a direct link between military capability requirements on the one hand, and strategic risks and strategy on the other.”16

With the risk from the unprecedented expansion of PRC military capabilities being recognised by the Australian Government, the focus for the nation’s defence planning must be on the development of capabilities to defend the nation and its interests.

ADF military capabilities must therefore manage the strategic risk. Key amongst these is the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Forces. This includes the DF-26 Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBM) that can reach northern Australia from China’s artificial island bases in the South China Sea. Their new DF-27 IRBM, equipped with a hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) warhead, is believed to have moved from development into deployment. This missile has a range of 5,000 km to 8,000 km and is “believed to be primarily [designed]…for regional conventional strikes during conflict.”17 The DF-27 brings virtually the entire Australian continent under risk.18

The People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) H-6K bombers can range Australia with CJ-20 Land Attack Cruise Missiles (LACM) and Air-Launched Ballistic Missiles (ALBM). The PRC has also undertaken a major expansion of its submarine fleet, specifically its nuclear-powered guided-missile submarines (SSGNs). Over the last 15 years, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has built 12 new submarines, including four Type 093A Shang III class SSGNs, which provide a new class of anti-surface warfare and land-attack capabilities. The expansion of the PLAN’s SSN capability is part of its transition “from defense on the near seas to protection missions on the far seas.”19 It is estimated that China has built seven or eight Type 093B SSGN submarines, equipped with 12 vertical launch missile cells — including those for the YJ-21 hypersonic missile — in the past three years.

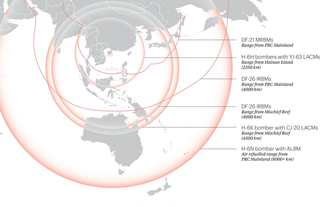

These developments were highlighted in a 2024 Lowy Institute report, which outlined the PRC’s growing military capabilities in the South China Sea. The report included a map that represents the effective reach of PRC military power. This map (see Figure 1) highlights the risks that Australia could face and the character of the changing regional strategic balance, not only in Asia but also in the eastern Indian Ocean.20 As the report noted, “China’s recent military development constitutes the greatest expansion of maritime and aerospace power in generations and is most obviously seen in its expanding long-range missile force, bomber force, and modernising blue-water navy.”21

Figure 1. The increasing reach of China’s strike capabilities

DF-21 and DF-26 mainland ranges measured from open-source estimates of associated PLA Rocket Force bases. All ranges are approximate given source limitations.

The map highlights the geographical proximity of northwestern Australia and Australia’s Indian Ocean territories to the maritime choke points at the hinge of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, including the South China Sea and the Philippine Sea, and onward to Taiwan and East Asia. They also highlight not just the criticality of this region but also the importance of the ADF’s network of northern bases for the defence of the area (and for force projection into the region), and the genuine risk of cruise and ballistic missile attacks to northwestern Australia in the event of a major regional contingency.22

In modern-day terms, the risk and potential threat to northern Australia are both synonymous with that of 1942 and very different. During the air raids on 19 February 1942, the Japanese struck shipping in the harbour, the wharf, the town and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) airfields, killing 250, including 88 US sailors on the USS Peary, which was sunk in the harbour. At the time of this raid, the air defence of Darwin was concentrated around the Army’s ground-based anti-aircraft guns, principally 16 3.7-inch anti-aircraft (AA) guns and two 3-inch AA guns. There was no RAAF fighter aircraft available for the defence of Darwin at this time.

While the risk of a conflict in the Indo-Pacific remains, the contemporary threat profile is different, with long-range drones, cruise and ballistic missiles representing the most critical risks.

While the risk of a conflict in the Indo-Pacific remains, the contemporary threat profile is different, with long-range drones, cruise and ballistic missiles representing the most critical risks. If attacked today, current RAAF capabilities from bases in Darwin and Tindal, including F-35 Joint Strike Fighters and multirole F/A 18 Super Hornet aircraft, represent considerable defensive assets. This represents an inverse of the defensive focus in 1942; back then, the defensive effort fell to the Australian Army’s ground-based air defence (GBAD) system. Today, this is almost non-existent.

Currently, the Australian Army has very limited GBAD capabilities, with only two batteries of modern mid-tier National Advanced Surface-to-air Missile Systems (NASAMS) being brought into service. NASAMS is one of the world’s most advanced surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems, combat-proven against large UAVs, helicopters, aircraft and cruise missiles. Australia’s ground-based ballistic missile capabilities are, however, basically non-existent.

GBAD is only one component of air defence. Modern systems are built around the concept of Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD). IAMD is an all-domain responsibility with the Air Force, Navy, Army, Cyber and Space domains all playing essential roles. As such, the focus of this paper is on the options for building and developing the hollowest section of Australia’s integrated air and missile defence architecture: the Australian Army’s GBAD capabilities.

GBAD’s capabilities are the most limited, and the capability development curve is the steepest in terms of both mass and required effects. Most significantly, the lessons of recent and current conflicts underscore the importance of robust GBAD capabilities as a core element of any modern IAMD system. The ongoing war in Ukraine, the clashes between Israel and Iran and other modern conflicts have all highlighted the increased range and lethality of Uncrewed Aerial Systems (UAS) and cruise and ballistic missiles.

GBAD represents a critical capability gap for Australia.

The Ground-Based Air Defence challenge: International developments 2019-2025

Evidence of the criticality of GBAD in modern conventional conflicts has been mounting in recent decades. Missile threats have proliferated, and airpower is undergoing fundamental changes with the development of a range of Uncrewed Aerial Systems (UAS) capabilities and changes to IAMD capabilities.

The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War

During the 44-day Second Nagorno-Karabakh War from 27 September 2020 to 10 November 2020, Azerbaijan’s deployment of drones exposed Armenia’s vulnerabilities in traditional air defence. This provided Azerbaijan with crucial advantages in reconnaissance, targeting and long-range strike capabilities beyond front lines. In particular, the Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 “demonstrated the versatility of UAV platforms… In addition to providing identification and targeting data, the TB2s also carried smart, micro-guided munitions to kill targets on their own.”23

The use of drones in combination with artillery allowed Azerbaijan to target and disable Armenia’s air defences, leaving its military forces exceptionally vulnerable.24 Notably, the vulnerability of obsolete air defences to these new forms of attack was also evident. The use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) proved extremely effective against larger, high-end air defence systems such as the Russian S-300 systems.

Key lessons/takeaways

The key lessons were the need for “full-spectrum air defence”, the lethality of UAS against traditional air defence systems, and the importance of “passive defence…” with a consideration of “new ways to camouflage and harden their forces… In an age of highly proliferated sensors and shooters.”25 The lessons from the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, especially in the need for counter-UAS systems, had been apparent the year before with Iranian-backed Houthi rebel strikes on Saudi Arabian oil facilities.26 The September 2019 Houthi attacks cut Saudi oil production by 5.7 million barrels a day. They were part of a series of drone attacks over multiple months, which were effective due to legacy anti-missile and air defence systems not being designed to counter such threats.27

Iranian-Israeli Conflict 2024-2025

On 1 October 2024, Iran launched approximately 180-200 ballistic missiles, in two waves, as part of its Operation True Promise II. Most of these missiles, reportedly 90%, were intercepted.28 Israel has not confirmed the number of sites impacted by the strikes, but video and satellite analysis suggest that 20-30 missiles struck Nevatim air base, three struck Tel Nof air base, and at least two landed in Tel Aviv at Cinema City Glilot, Hod HaSharon.29

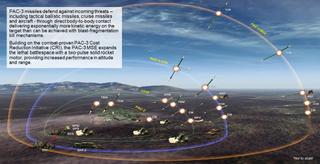

The effectiveness of the Israeli GBAD is well known. It provides a layered response comprising three critical elements. Firstly, the long-range Arrow System, which consists of Arrow 2 and Arrow 3 missiles, uses a “two-stage solid-fueled interceptor” aimed at defeating long-range ballistic missiles.30 The Arrow 3 system is designed to “destroy incoming ballistic missiles outside of Earth’s atmosphere, during their midcourse phase, before they descend toward their targets.”31

Secondly, a mid-tier system called David’s Sling, designed to defeat short-range ballistic missiles, large-calibre rockets and cruise missiles at ranges of 40 to 300 km.32 Finally, the inner-tier of defence is the Iron Dome system. This is a short-range system designed to defeat short and medium-range unguided rockets, which have been persistently launched against Israel in recent decades by Hezbollah and Hamas.

This system is supported and supplemented by Iron Beam, an experimental laser-based system designed to counter short-range rockets and UAS, as well as the Barak-8 (a surface-to-air missile system), used by the Israeli Navy. In addition, the United States has provided direct support to Israel through its own GBAD, mainly the US Army’s “Patriot PAC-3 (comparable to David’s Sling) and THAAD (comparable to Arrow 2)… the US Navy… Aegis and the SM-3 (comparable to Arrow 3) and the SM-6 (comparable again to Arrow 2)” missiles.33

The Israeli defences have proven remarkably effective over an extended period. From countering short-range rockets to the recent defeats of Iranian missile strikes over a persistent period.

US GBAD systems, especially the Patriot and THAAD, are in exceptionally high demand globally, making them one of the most heavily deployed capabilities in the US military. In 2015, the US Army’s air and missile defence forces were deployed in nine countries, and over the last decade, the demand has only increased.34 In 2023, the US Army had 15 Patriot Battalions (each comprising four batteries), with a further battalion in development, and was requesting an expansion of the force. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 included that “legislation also provides Army leaders with the authority to grow the Patriot force up to 20 battalions.”35

Critical to Israel’s defence is a layered and IAMD approach. Their defences are both joint and combined. In the April 2024 attacks, “At least nine countries were involved in the military escalation — with projectiles fired from Iran, Iraq, Syria and Yemen and downed by Israel, the US, the UK and Jordan.”36 This demonstrates the critical importance of regional partnerships for a successful collective missile defence.37

Israel Defense Force (IDF) defences are also joint by design. Land-based systems are supported by aircraft firing air-to-air missiles, including 5th Generation aircraft such as the F-35, and ships firing naval-launched SAMs. Supporting these systems are cyber capabilities, space surveillance, and a network of land, air and sea-based radars and early warning sensors.

The backbone of the defence, though, is the ground-based systems. Only these systems possess the persistence and capability required to deliver on their primary mission of continuous air and missile defence. Naval ships and aircraft have other mission sets. Limiting strike aircraft and naval vessels to IAMD missions, especially homeland defence, vastly restricts their availability in times of conflict to other vital mission requirements, such as counterstrike, and renders them more discoverable and vulnerable by their restrictions to geographically locked-in defensive areas.

The Israeli defences have proven remarkably effective over an extended period. From countering short-range rockets to the recent defeats of Iranian missile strikes over a persistent period. In early June 2025, Israel began a wave of attacks on Iran under Operation Rising Lion, designed to respond to Iranian-backed attacks on Israel by Hezbollah and Hamas as well as to strike at Iranian nuclear facilities and long-range weapons. Iran responded to these attacks similarly to October 2024, firing 200 ballistic missiles supported by 200 drones. Given the distances involved, with Iran around 1,000 km from Israel, Iranian strikes were primarily based on medium-range ballistic missiles; high-speed, high-altitude threats that are difficult to track, engage and destroy. The Iranian attacks were also launched in waves with supporting UAS strikes to attempt to overwhelm the Israeli defences. Again, Israel’s defences withstood the Iranian attacks with an exceptionally high degree of proficiency. It reported that all the UAVs were destroyed, and most missiles were intercepted.38

As the Iranian strikes persisted over the following days, the defences held firm, with only a small number of missiles breaking through. One of the key factors in Israel’s defences in the June 2025 conflict was the IDF’s ability to undertake counter-air missions against the Iranian missile sites. This could only be achieved after the IDF was able to dismantle Iran’s IAMD system. This effectively meant that the IDF could attack the launch sites or the ‘archers’ rather than waiting to defend against their ‘arrows’ by focusing on shooting down missiles. The foundation for this approach was the release of the IDF air force to conduct strike missions inside Iran. This was only possible due to the strength of the IDF GBAD, which allowed Israel to always have ‘one foot on the ground’ for its missile defence, enabling it to strike out against its adversary at the source of the Iranian missile strikes.

As effective as the defences have been, they also suffer from the perennial missile defence issues: the limited number of interceptors available and the cost-curve issue — the cost of the incoming missile relative to a more expensive one to intercept it, creating an imposition on the defending nation.

As effective as the defences have been, they also suffer from the perennial missile defence issues: the limited number of interceptors available and the cost-curve issue — the cost of the incoming missile relative to a more expensive one to intercept it, creating an imposition on the defending nation. However, this is offset by the cost of the defended asset, whether in terms of lives (civilian or military) or military capability, such as an airbase, industrial facilities, headquarters or a naval task group.

Key lessons/takeaways

Noting this, the key takeaways from the Israel-Iran conflicts of recent years include the large quantities of defensive weapons required, particularly when seeking to intercept multiple targets; the importance of an integrated system; and the significance of the industrial base in producing GBAD systems and missiles.39 This conflict also highlighted the effectiveness of Israeli attacks on Iranian IAMD systems that paved the way for President Trump’s air attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities.

These lessons, though, are not necessarily universal, as one analyst remarked, “Beijing’s missiles would be more difficult to intercept than Iran’s and that the ability to strike back would be needed to deter a mass attack.”40 The PRC’s more capable military would mean that Chinese missile attacks would most likely be coordinated with anti-satellite strikes and cyberwarfare, both designed to complicate defences. “Western (integrated air and missile defence) systems in the Indo-Pacific would have a much tougher time defeating a large Chinese missile strike, comprising hundreds or even thousands of missiles, compared to what the Iranians are capable of.”41

Russia-Ukraine War

The ongoing war in Ukraine after Russia’s invasion provides another contemporary conflict reference point, demonstrating the effectiveness of GBAD systems. In early 2022, it was estimated that Ukraine was only capable of intercepting between 20 and 30% of Russian missiles. By 2023, it was estimated that this had risen to 90% due to the introduction of modern Western air-defence systems, such as the NASAMS and surface-launched IRIS-T systems, to the Ukrainian military. Ukraine has constantly sought an expansion of Western air defence systems. In July 2024, then-US President Biden announced, “The United States, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania and Italy will provide Ukraine with the equipment for five additional strategic air defense systems.”42

The ongoing war in Ukraine has also demonstrated the effectiveness of GBAD systems. The United States has provided over 1,000-man portable (MANPADS) Stinger missiles and a fleet of Avenger air defence systems (mobile Stinger launchers fitted to a Humvee chassis). One of the most effective systems has been the NASAMS air defence systems, which were initially delivered to Ukraine in November 2022 through the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative.43 Spain, Sweden, Germany and Poland have also provided modern air defence systems.44

Aside from this, two of the most effective systems deployed in Ukraine have been the Norwegian NASAMS system and the US Patriot system. These two GBAD systems have proven to be complementary and mutually reinforcing. Both have different mission sets, with NASAMS being a highly effective mid-tier system against class-3 UAS, aircraft and cruise missiles, and Patriot being more effective against ballistic missiles and high-altitude, longer-range targets. These systems have become mutually supportive, with Ukraine consistently deploying them together, maximising their effects and minimising the vulnerabilities of each system.45

NASAMS

NASAMS has proven to be an exceptionally effective system in Ukraine, with a 94% effective hit rate. It is one of the core elements of their GBAD system, particularly against low-profile, map-of-the-earth Russian cruise missiles. Ukraine currently fields 13 complete batteries and parts of three additional batteries, with support of this capability coming from Norway, Lithuania, the United States and Canada.46

The system has also been used by Ukraine as a point defence against short-range ballistic missiles, even though this is not its primary air defence profile.47 “Around 60% of intercepted targets were cruise missiles, including the Kh-101, Kh-555, Kh-59, and Kh-69, as well as Kalibr and Iskander-K missiles,” the remainder being UAVs, mainly loitering munitions (suicide drones).48 Ukraine has linked up to 17 launchers to a single NASAMS fire distribution centre (FDC), which provides a highly effective Battle Management, Command, Control, Communications, Computers and Intelligence (BMC4I) system.49

The Patriot system

The United States agreed in October 2022 to send Ukraine the Patriot missile systems, which became operational in April 2023. As of 2025, Ukraine has received six operational batteries, two each from the United States and Germany, one from Romania and a composite battery from Germany and the Netherlands. Since deployment, the Patriot system has shot down Russian air-launched Kh-47M Kinzhal hypersonic missiles, capable of speeds between March 5 and Mach 10 (5,960 km/h).50 It has also shot down Su-34 fighters at over 160 km away, and intercepted missiles as far as 200 km away. It has also destroyed Russian ‘Iskander’ missiles and North Korean KN-23s.51 The Patriot system’s most effective missile is the PAC-3 MSE, an “endoatmospheric point defense system with a capability to intercept short-range tactical ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and military aircraft…that uses hit-to-kill technology.”52 Lockheed Martin, which produces the missile, has hit a production rate of 550 missiles per year, with an expectation to grow to 650 per year by 2027. Currently, 19 countries operate the Patriot system, deploying over 250 fire units worldwide.53 The deployment of the Patriot system to Ukraine has enabled more advanced combat testing, resulting in “critically important software updates and improvements to the hardware.”54

The Patriot system in Ukraine has been an “unmitigated success,”55 making it one of the key reasons why Ukrainian President Zelenskyy has consistently urged the provision of additional air defence systems. In April 2025, he requested that US President Trump allow him to purchase ten additional Patriot systems at an estimated cost of US$1.1 billion each.56 In June 2025, President Trump noted that he is considering Ukraine’s request during the NATO summit; however, he raised concerns about the need for these systems in Israel and also in the United States.57 This has highlighted two of the most critical issues for Ukraine and its western backers. The first is the high cost of missile interceptors with PAC-2 and PAC-3 Patriot missiles costing between $2 million and $4 million each.58 The second is that there is a critical shortage of global munitions production. This was reinforced by US Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Elbridge Colby’s unilateral decision to pause weapons transfers to Ukraine in July 2025 over concerns for low weapons stockpiles, including Patriot missiles.59

As demonstrated here, critical for Ukraine’s long-term strategic survival in the war was the GBAD’s ability to be “instrumental in protecting civil and military infrastructure.” Ukraine’s GBAD system has thus ensured the “ability to maintain and protect combat essential units and, ultimately, the war effort.”60

Key lessons/takeaways

Among the range of lessons emerging from Ukraine’s experience, the most seminal is the importance of mobility and dispersion for GBAD assets. Static defences proved exceptionally vulnerable, and in the first 48 hours of the conflict in Ukraine, Russia “succeeded in engaging 75% of static defence sites.”61 Only through “dispersing its (Ukraine’s) arsenals, aircraft and air defences” and the mobility of key assets such as SAM launchers and radars, were they survivable.62 “Not allowing Russia to easily target their GBADs, as could be done against fixed anti-air systems, has provided Ukraine the defensive edge.”63 Keeping its air defence systems intact, Ukraine solidified an anti-access/air-denial (A2/AD) area capability through the innovative use of its available systems.

The reinforcement of the layered system of defence is another key lesson. For example, larger air defence systems, such as Patriot and NASAMS, have targeted Russian aircraft at high altitudes, forcing them to fly low-level mission profiles, bringing them into range of Stinger MANPADS and Avenger short-range air defence (SHORAD) systems. MANPADS has also been successful in combating attack helicopters and Iranian-made loitering munitions. In this, a much larger and more technically sophisticated Russian air force has been unable to defeat Ukraine’s IAMD system. This was due to Ukraine’s deployment of highly agile and portable ground-based air defence (GBAD) systems. This has allowed its air force — “inferior qualitatively and quantitatively to Russia’s — to dissipate firepower, while preventing Russia from easily targeting its GBADs… [This has ultimately solidified] an anti-access/air-denial (A2/AD) area… [capability built through] layer upon layer upon layer utilisation of air defence systems… integrating multiple air defence systems, such as S-300s and MANPADS, Ukraine has created an A2/AD area that poses a high risk for the Russian Air Force.”64

Last of the key lessons from Ukraine has been the ability to integrate disparate systems, such as radars, missiles and launchers, from different countries and form them into a functional IAMD architecture delivering a layered defence, with minimal viable integration, driven by threat-based responses. These have mainly been military-off-the-shelf (MOTS) assets, using proven systems. This is a classic example of a minimal viable capability achieved through MOTS, rather than the search for a perfect solution.

Critical lessons identified from contemporary conflicts

A range of critical lessons can be identified for GBAD and IAMD from conflicts in the Middle East, the Caucasus region and Europe. These can be summarised as:

- The importance of a layered GBAD defence that covers counter-UAS to mid-tier cruise missiles, hypersonic missiles, and high-performance aircraft to short and intermediate range ballistic missiles.

- The criticality of GBAD for IAMD, providing persistence, deployability and a firm ‘one foot on the ground’ for defensive forces.

- The importance of GBAD to release air force and navy capabilities from close-in defence to undertake strike and counter-air missions deep into the battle space.

- The viability of military-off-the-shelf solutions and the importance of minimal viability capability and minimal viable integration. This is especially apparent in Ukraine with their adoption and integration of a range of different systems and GBAD solutions. This is also evident in Israel with the adoption of Patriot, THAAD and other systems into their IAMD architecture.

- The centrality of integrated. This begins with minimal viable integration and progresses to optimal integration, ultimately improving outcomes and performance.

- The critical importance of interchangeability of data, systems and information. As this is difficult to accomplish once a conflict breaks out, programs to achieve interchangeability during the competition phase are essential, as policy settings can be easily adjusted in conflict without pre-commitments to allies or partners.

- The importance of camouflage and concealment in a high-sensor and threat environment, including electronic warfare, as well as repair capabilities and functions for enhanced resilience.

- The global shortage of GBAD systems, including in the US Army.

- The vulnerability of fixed sites and systems, radars, launches, fire control, etc. They will be targeted early as a priority.

- The need for GBAD systems to be highly deployable and highly manoeuvrable.

- The high volume of interceptors required.

- The importance of industrial capacity.

- The importance of allies and partners in developing a network approach to IAMD, including industrial capacity and development.

- The need for research and development, especially to expand non-kinetic options for air defence and to develop systems that reduce the cost-to-kill ratio for interceptors against cruise and ballistic missiles.

- The importance of calculating the cost of the protected assets (civil and military infrastructure, capabilities, civilian and military lives, morale, national capacity, etc.) in the cost-kill-ratio for IAMD.

Integrated Air and Missile Defence and the Indo-Pacific

All lessons from recent conflicts in IAMD need to be assessed against the geography, strategic situation, threats and circumstances of the Indo-Pacific theatre of operations. There is no doubt that IAMD is a global defence issue and central to deterrence in the Indo-Pacific region.

US Ground-Based Air Defence investment

For the United States and its allies in the Indo-Pacific, the PRC is the pacing threat. In recent years, the primary responsible capability manager for air defence in the US system — the US Army — has placed an increased premium on these capabilities. In July 2025, the US Army announced the acquisition of four new Patriot battalions, one of which will go to Guam.65 These battalions will come with the new Lower Tier Air and Missile Defense Sensor (LTAMDS), which detects and defeats advanced threats, including ballistic and hypersonic weapons.66 This allows the Patriot system to operate more distributed. This will critically enhance capability as the US Army argues that the use of LTAMDS “greatly expands the range, the altitude, and [provides] 360 [degree coverage]… and fundamentally when you operationally employ it, it’s immediately doubling that capability… You would have the equivalent of about 30 Patriot battalions because instead of having to deploy as batteries, you can break them up and disperse them in a much more tactical way.”67

The July 2025 announcement is part of a dedicated approach to placing more importance on GBAD systems in the US Army. In March of 2024, the US Army allocated “[US]$602 million in research and development efforts for Integrated Air and Missile Defense and [US]$2.8 billion in procurement, which covers modernized capabilities beyond the Patriot system” for the 2025 fiscal budget.68

For the financial year 2026, the defence budget for the US Army reflects a clear strategic shift to air and missile defence systems (along with hypersonic weapons and unmanned platforms). Procurement in air and missile defence is up 14.2% on the previous financial year budget. The financial year 2026 budget provides for increased investment in the Patriot system, including an uptick in procurement of the PAC-3 Missile Segment Enhancement (MSE) and for the Patriot Modifications program (US$757 million).69 The Patriot Modifications program includes increases to the system’s “capability, readiness and sustainability,” logistical support, cybersecurity and electronic warfare.70 This budget includes PAC-3 MSE acquisition increases from 3,376 to 13,773 missiles, as approved by the Army Requirements Oversight Council Memorandum (AROCM) on 16 April 2025.

This budget includes US$1.3 billion for the LTAMDS radar system, which detects advanced threats, including ballistic and hypersonic weapons.71 LTAMDS has been selected by Raytheon as the new radar for the Patriot system, providing 360-degree coverage. It was approved in April 2025 to “double legacy Patriot radar capability” as part of the US Army’s modernisation plans,72 indicating that the Patriot system will remain in use for the long term.

Additional investments for GBAD included US$729 million for the mobile short-range system (M-SHORAD).73 This comes off the back of a 2024 investment into Indirect Fire Protection Capability battalions,74 UAS batteries, M-SHORAD battalions and an expansion of air and missile defence at the corps and division levels.75

The US Indo-Pacific Command and Integrated Air and Missile Defence

IAMD has long been a priority for the United States Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM). In 2018, INDOPACOM released the “Integrated Air and Missile Defence Vision for 2028” (hereafter, IAMD Vision 2028), which seeks to secure the United States’ competitive advantage in the Indo-Pacific region and to establish an integrated defence network with allies and partners, as well as outlining an ambition for a regional integrated fire-control architecture. At the heart of this vision is the development of a common operating picture. This initiative builds off the 2014 Pacific Integrated Air and Missile Defense Center “designed to be a joint and multinational organization that educates and trains military and partner nation IAMD operators and planners.”76

For the past four years, the US Army has hosted a Multilateral Integrated Air and Missile Defence Summit. The December 2024 edition yielded various observations to advance IAMD in the Indo-Pacific region. Major Michael Parry, an Australian Army Artillery officer serving with the US Army’s 94th Army Air and Missile Defense Command as part of the AUS/US Military Personnel Exchange Program, observed at the 2024 summit that the outcomes underscored a critical shift in the threat environment. He noted that “the proliferation of hypersonic missiles, low-altitude cruise missiles, UAVs, and integrated attacks… [has eroded] traditional notions of sanctuaries… previously secure locations like Australia now require enhanced defensive strategies and capabilities.”77

With the absence in the Indo-Pacific of a NATO-like defence framework, Parry noted that participants emphasised:78

the need for robust data-sharing agreements, joint exercises, and persistent command and control architectures for real-time coordination [and that]… Space-based capabilities emerged as a crucial element of regional defence…Nations must integrate space-based missile warning, tracking, and countermeasures into broader defence frameworks.

IAMD Vision 2028 also aims to address the critical importance of cooperation between allies and partners, as well as the need to integrate systems. Its core concepts include the need for:79

a network architecture that all allies/partners can share and ‘any sensor, any shooter’ in the region can leverage to thwart an incoming threat… [and] area of responsibility (AOR)- wide integrated, netted, and layered sensor coverage.

Given the vulnerability of fixed sites and fixed defences, the IAMD Vision 2028 is built around concepts of agile basing for air forces. Overall, this vision aims to resolve capability and capacity issues through integration with allies and partners, by ‘synergising sensors and interceptors’ to increase capacity and survivability. One of the key lessons relevant to IAMD Vision 2028 from the conflicts in Ukraine and Israel is the need to focus on minimum viable integration, rather than letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

Progress towards the integration of allies and partners as components of this vision has been made. The US Army has begun to field an Integrated Battle Command System (ICBS), while the US Air Force has developed an Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) to replace legacy Command and Control (C2) systems. This system aims to collect, process and share data across all domains to enable better decision-making. In Australia, Project AIR6500 has focused on its Joint Air Battle Management System (JABMS) to strengthen situational awareness and improve interoperability with allies and partners.80 While a solid start, full-spectrum ‘plug and play’ integration is extraordinarily challenging and remains only an ambition.

Testing Vision 2028 Integrated Air and Missile Defence coordination in the Indo-Pacific

The ambition for plug-and-play integration is central to the medium- to long-term development of an integrated IAMD architecture for the Indo-Pacific. This approach was tested by the United States Studies Centre (USSC) in June 2025 in a detailed theatre-wide Table Top Exercise (TTX) involving former senior military officers and officials from the United States, Australia, Japan, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan. The TTX assessed the strategic value of allied IAMD capabilities through four vignettes featuring mixed-country teams generating IAMD architectures across a range of contingencies from limited to major conflict scenarios.

This activity was designed to assess various constraints (capability, budgetary and coordination) for a range of sensors and effectors, as well as coordination across countries. Players in the TTX teams analysed the relative performance of each IAMD architecture in terms of intercept rate; inventory management (magazine depth, reload time, prioritisation, etc.); redundancy (i.e. in terms of single points of failure); survivability; situational awareness; and cost-per-engagement. This was done to address the IAMD performance costs of capabilities and coordination (or lack thereof).

The high-level takeaways of this TTX reinforced the integration focus of IAMD Vision 2028 and the direction of development of the US Integrated Battle Command System and Advanced Battle Management System, and Australia’s Joint Air Battle Management System. The USSC TTX demonstrated that international integration of IAMD across multiple domains, including planning, system development and procurement, track and data sharing, battle management and fire control, yields major efficiencies in cost and performance (effectiveness).81

The other major identified outcome was the criticality of GBAD as the foundation of IAMD. A robust GBAD system provides for long-term presence, sensor diversity, distributed fires and depth of magazines. Most importantly, a foundation built around GBAD allows naval and air assets to conduct intercepts or counter-air missions across the entire battle space, providing depth to IAMD and significantly improving force protection and mission outcomes. It dramatically complicates the strike planning of adversaries, including the requirement for greater allocation of resources to achieve reduction/degradation of defensive systems. This also generated a deterrence effect as it improves the inventory imbalance between the adversaries’ strike capabilities and the IAMD capabilities.

The extraction of maximum efficiencies in cost and performance was driven by the need for nations to coordinate the purchase of strategically complementary IAMD systems. The acquisition of complementary capabilities and systems cultivated economies of scale in the supporting defence industrial base, including manufacture, maintenance and sustainability, improving readiness and preparedness. Such an approach also promoted interoperability/interchangeability, generating efficiencies in collective IAMD performance (survivability, situational awareness, etc.) by directing the procurement of national capabilities to meet national strategic needs while also filling coalition capability gaps.

While offering major advantages, this approach still faces constraints, including national needs at the strategic and political levels, which necessitate positioning costly IAMD procurements within national force structures and strategy. Other restraints include the potential for a mismatch between national and Coalition Air and Missile Defence (CAMD) requirements, a trust dilemma in integrating IAMD procurement with allies and partners, a technology and security gap between different allies and partners, national service cultures and approaches to prioritising IAMD and the allocation of budget resources.

Despite these limitations, the sharing and integration of target tracks and data across the represented countries repeatedly emerged as the major priority for the participants, implying the strong viability of track and data sharing arrangements between these states in a conflict situation. The main barrier to this was the development of the ability to undertake track and data sharing in the pre-conflict competition phase. This was assessed as much easier in the US-Australia alliance, given their high level of interoperability based on their mutual security and force protection standards, mutual advanced technology, people-to-people links, and integrated approach to training, operations and doctrine.

The major barriers to effective coordination were the development of policy to address ongoing challenges in internationally coordinating IAMD, including political and technical barriers. The key factor is that, internationally, IAMD cooperation — especially in terms of system interoperability, track and data sharing — offers major advantages for the development of robust A2/AD systems. Efforts to achieve this, however, as demonstrated in recent conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, must be offset by the need to start with minimum viable integration and the need to balance integration budget priorities with the need to deliver effective results. Situational awareness is key, but it must be delivered with capabilities to kinetically counter air and missile threats.

Policy development and coordination in AJUS (Australia-Japan-the United States)

Work has also developed tri-laterally in the Indo-Pacific to advance coordination in the Indo-Pacific. The AJUS countries — Australia, Japan and the United States — have agreed to establish a regional IAMD network to develop advanced capabilities. During the Japan Official Visit in April 2024, the United States and Japan announced their intention to partner with Australia to build a regional architecture that incorporates the three countries’ sensors, with plans to test this network during a live-fire exercise in 2027.82 Similarly, the United States and Australia announced during the Australian official visit in October 2023 that they would partner with Japan to develop collaborative combat aircraft that would team with manned fighter aircraft and perform support missions, such as aerial refuelling and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.83 The partners have made incremental yet steady progress toward achieving this capability. This provides an excellent platform to advance regional IAMD coordination.

The state of play in Australia

As noted above, IAMD and especially GBAD have not been a priority for the Australian Defence Force (ADF) since the Second World War. In the post-war period, the Australian military fought under US and allied air superiority or supremacy in campaigns in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. The changing nature of the Indo-Pacific strategic environment and the re-posturing of the ADF for potential major conflict in the region have revealed that the ADF’s IAMD capabilities, particularly its GBAD capabilities, are not fit for purpose.

Australia’s flagship capability development program for IAMD is AIR6500. Launched in 2016, the project has undergone several revisions to its design. However, from 2018, it was built around a range of projects, including:

- AIR6500 — Joint Air Battle Space Management Project (JABSM)

- AIR6502 Medium-Range Ground-Based Air Defence

- AIR6503 Advanced Missile Defence System

These projects were designed to complement and integrate with:

- LAND19 Phase 7B Short Range Air Defence (NASAMS)

- SEA400 Air War Destroyer Upgrade

- SEA500 Future Frigate program

- E-7A Wedgetail airborne early warning and control aircraft

These capabilities represented an RAAF-led “project through an Integrated Air and Missile Defence Multi-Domain Program Management Office formed in early 2020.”84

AIR6500 has been designed around a ‘systems-of-systems’ approach — receiving, processing and disseminating data across domains to allow Defence to coordinate air and missile defence operations and to facilitate decision-making. It is an ambitious project aimed at enhancing situational awareness for the ADF, as well as ensuring interoperability with allies and partners.

AIR6500 Phase 1 — JABMS has been the core of the program. Tranche 1 of JABMS has focused on radar deployment, acquiring four Active Electronically Scanned Array radars procured from the Defence-owned Australian CEA Technologies company.85 In April 2024, Defence selected Lockheed Martin as its Strategic Partner to implement AIR6500 Phase 1 Tranche 2 JABMS. JABMS is ultimately the ‘brain of the system’86 and is designed around spiral development, an agile methodology and an open architecture designed to integrate both legacy and new technologies.87 By 2026, it will deliver key replacements to the RAAF’s air surveillance and deployable air traffic control systems.88

AIR6500 Tranche 1 and Tranche 2 have been the focus of the program, leaving AIR6502 and AIR6503 with minimal government funding and, consequently, limited development. Critics of the program today have argued that there is too much focus on situational awareness and battlefield coordination, with AIR6500 promising to solve integration problems across the ADF, and that it is attempting to address issues that the US$141 billion per annum Pentagon investments into research and development have not been able to solve. Questions have also been raised about the slow pace of procuring effectors, with AIR65002 stalled and AIR6503 all but discontinued. The reorganisation of the program in 2024 saw the withdrawal of projects AIR6502 and AIR6503 and their consolidation into AIR6500, which is designed around phases. This has raised further concerns about strategic, capability and budget priorities for IAMD.89 As one commentator has argued, the focus and funding of AIR6500 Tranche 1 and 2 over other programs in IAMD has led to AIR6500 being “effectively toothless.”90

Australia’s strategic policy guidance for Integrated Air and Missile Defence

2023 Defence Strategic Review

In 2022, the Albanese government commissioned former Labor defence minister Professor the Hon Stephen Smith and former Chief of Defence Force Air Marshal (Rtd) Sir Angus Houston to undertake an external review of defence strategy, capability and force posture. The subsequent 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) recommended a range of adjustments to the ADF, starting with the premise that Australia has entered a new strategic era and that the current ADF is ‘not fit for purpose’ in this new age.91

The DSR recommended that the Australian Government adopt a regional balancing strategy focused on collective deterrence in the Indo-Pacific, along with allies and partners, and a military strategy of denial for the ADF. This included a new focus on developing the ADF as an integrated force, building national resilience, establishing a robust northern base network for the ADF to operate from, fielding new capabilities, expanding defence industrial capacity, particularly in guided weapons, and increasing national investment in defence and security.

The ADF’s denial strategy was to be built on the development of key anti-access, area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities for the ADF. In developing this denial approach, the subsequent National Defence Strategy and Integrated Investment Plan in 2024 focused capability development around the ADF’s ability to field and deliver long-range strike capabilities from land, sea and air. To establish capabilities to execute a denial strategy and build an effective A2/AD system, it is just as essential, however, for the ADF to field more defensive-oriented systems, such as IAMD.

For IAMD, the DSR concluded that the approach in AIR6500 was not fit for purpose. The DSR concluded that:

Defence must deliver a layered integrated air and missile defence (IAMD) operational capability urgently. This must comprise a suite of appropriate command and control systems, sensors, air defence aircraft and surface (land and maritime) based missile defences…

Defence’s medium-range advanced and high-speed missile defence capabilities should be accelerated…

While we are supportive of Defence’s approach to developing an ADF common IAMD capability, we are not supportive of the relative priority that the program was given. The program is not structured to deliver a minimum viable capability in the shortest period of time but is pursuing a long-term near perfect solution at an unaffordable cost…

In-service, off-the-shelf options must be explored….

Defence must reprioritise the delivery of a layered IAMD capability, allocating sufficient resources to the Chief of Air Force to deliver the initial capability in a timely way and subsequently further develop the mature capability.92

While the direction and intent of the review are clear, the DSR had one major failing: it left off a specific set of recommendations consistent with the text in the body of the document. The Australian Government’s direction to Defence to focus on the DSR’s recommendations and bureaucratic politics has contributed to a lack of funding for IAMD and an inadequate prioritisation in the 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS) and Integrated Investment Plan (IIP).

The 2026 NDS and IIP are an opportunity to rectify this erroneous position.

Drafting aside, the intent of the DSR is clear, and the mission essential. The text of the DSR is clear — the current approach is not fit for purpose, and the need is urgent. IAMD must be “accelerated,” the focus must shift to delivering “minimum viable capability,” through “off-the-shelf options.”93

None of this has happened since the DSR was released.

2024 Defence Strategic Guidance

In 2024, the Albanese government produced a range of policy documents to formalise the outcomes of the 2023 DSR. This included a National Defence Strategy, an Integrated Investment Plan, a Defence Industry Development Strategy (DIDS) and a Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance (GWEO) Plan.

Upon receiving the 2023 DSR, the Albanese government agreed to 105 of the 108 recommendations.94 The declassified public version includes 62 recommendations, “all of which the Australian Government have either agreed with, or agreed with in-principle.”95 To take formal carriage of the new strategy and develop the Review’s recommendations into government policy, the Albanese government directed Defence to prepare a National Defence Strategy (NDS) in 2024. This document, a recommendation of the DSR, introduced a new structural mechanism for setting defence policy. Gone were the Defence White Papers that had been published at irregular intervals since the early 1970s at the Australian Government’s direction. Instead, the NDS process was to occur every two years, accompanied by a corresponding Integrated Investment Plan (IIP).

The 2024 NDS and IIP with sustainment, operations and workforce support are, in essence, execution documents for the strategy and direction outlined in the DSR.

This is not to say that IAMD and GBAD have only been developed since the DSR. The 2009 Defence White Paper identified “emerging capabilities priorities” that included “ballistic missile defence” with a focus on “examination capability options appropriate to Australia’s strategic circumstances.”96 Four years later, the Gillard government’s 2013 Defence White Paper committed to continuing “to examine potential Australian capability responses.” Interestingly, both White Papers rejected “the development of national ballistic missile defence systems” such as President Donald Trump’s ‘Golden Dome’, arguing that “they would potentially diminish the deterrent value of the strategic nuclear forces of major nuclear powers.”97 Neither of these White Papers raised concerns about cruise missile defence.

The 2016 Defence White Paper was more expansive. It expressed concern around the “growing threat posed by ballistic and cruise missile capability and their proliferation in the Indo-Pacific and Middle East regions.”98 It recommended Australia “increasingly develop capabilities which can protect our forces when they are deployed across large geographic areas, particularly in air and missile defence and anti-submarine warfare, and better link the ADF’s individual capabilities to each other.”99 It also noted an Australia-US bilateral working group to “examine options for potential Australian contributions to integrated air and missile defence in the region.”100 Four years later, the 2020 Defence Strategic Update stated, “The survivability of our deployed forces will also be improved through new investments in an enhanced integrated air and missile defence system and very high-speed and ballistic missile defence capabilities for deployed forces.”101

Fast forward to the 2024 NDS, and there is little mention of IAMD, and it is not identified as a priority. Instead, strike capabilities or ‘impactful projection’, continuous naval ship building and AUKUS were the main priorities, leaving insufficient funding to prioritise defensive capabilities like IAMD.

In the capability development section of the NDS, IAMD is not part of the Australian Government’s six immediate priorities announced in response to the Defence Strategic Review. Instead, “missile defence to protect critical Defence infrastructure, Defence facilities and the ADF from long-range and high-speed missile capabilities” is listed in capability priorities ‘across the coming decade’, meaning that the urgency listed in the previous strategic guidance, particularly the DSR, was not being actioned and didn’t flow through to the IIP due to funding and capacity offsets.102

There is no mention of GBAD as part of land capability priorities, and the only existing AIR6500 JABMS project is mentioned, “to integrate the ADF’s air and missile defence capabilities.”103 The only other reference to IAMD is in the North Asia strategic environment section: “The Government will continue to strengthen strategic alignment and coordination with Japan including… Advancing our cooperation on integrated air and missile defence, counterstrike, undersea warfare, and increasing Japan’s participation in force posture initiatives in Australia.”104

The 2024 IIP is more expansive, dedicating a whole chapter to IAMD, noting that:105

Military modernisation has enabled more countries to project combat power across greater ranges within our region through advanced long‑range and high‑speed missile capabilities. In this context, our integrated, focused force needs capabilities that can defend against, and reduce the effectiveness of, air and missile attacks.

The 2024 IIP outlines Defence’s layered approach and its current focus on sensors, command and control and integration. The active missile defence measures are limited to upgrades to the Aegis combat system on the Navy’s air warfare destroyers, which will also be fitted to the new Hunter class frigates, to allow integration of SM-2 and SM-6 missiles, and the existing F-35A and F/A‑18F Super Hornet fleets.

This approach leaves critical vulnerabilities in the ADF’s approach to IAMD. Firstly, the focus on RAAF capabilities is both essential and limiting. Without an effective GBAD system, RAAF assets such as F-35s and F/A-18F Super Hornets may be heavily restricted in their mission tasking with an undue emphasis on combat air patrols for air and missile defence missions; missions that would be constrained by fuel and tanker aircraft requirements to sustain defensive combat air patrols. Such an approach would also severely limit the RAAF’s ability to provide deep-strike counter-air missions that add critical depth to IAMD architectures and posture, let alone the limiting effect on other air missions due to availability.

Secondly, the Royal Australian Navy’s (RAN) main IAMD asset — until the Hunter Class frigates, future frigate and autonomous arsenal ships come online in the 2030s — are three Air Warfare Destroyers (AWDs). Like RAAF assets, the best use of these ships is to provide depth in the battle space, situating them as far forward as force protection allows to provide multiple intercept points with their advanced SM-2, SM-3 and especially SM-6 missiles. Point defence of critical infrastructure and assets onshore is a much less effective use of these assets.

Robust GBAD capabilities would enable the RAN’s AWDs to undertake task force and task group missions, protecting other RAN assets or participating in coalition operations across the theatre. Yet, the three RAN AWDs will progressively come offline starting from 2025 to upgrade their combat systems to Aegis Baseline 9 — giving them the capability for ballistic missile defence, integrating the Tomahawk Weapon System, and incorporating Saab’s new Australian combat interface along with several other improvements.106 Given the length of these major upgrades, at least one AWD will be unavailable at any given time over the next few years, with the potential for two or even all three to be in various stages of refit and thus unavailable for operations.

The only mention in the 2024 IIP of GBAD is the NASAMS system, which has already been acquired and is expected to achieve full operational capability in late 2025 or early 2026, as well as the development of the counter-UAS system. Regarding future GBAD priorities or acquisitions, there is no mention of either AIR6502 or AIR6503 or its replacement phases in AIR6500.

The IIP outlined in Table 1 is the proposed investment for IAMD. There is no GBAD list in this table, as all the named areas are either sensors or RAAF projects. This includes up to A$15.39 billion for the RAAF’s JABMS system and only A$3.77 billion for ‘active missile defence’.

Table 1. Australian Government investments in missile defence

The 2024 NDS and IIP have thus downgraded the urgency required in the DSR and previous policy documents dating back almost a decade, at a time when recent and ongoing conflicts have provided the opposite lessons for IAMD and GBAD. As one commentator has noted:107

[The] National Defence Strategy and its associated acquisition plan, the Integrated Investment Program, appear to have cut funding for the surface-to-air systems, the engagement component of integrated air and missile defence (IAMD). While a joint air battle management system will be bought under the previously announced AIR 6500 Phase 1 program, the updated acquisition plan says addition of other active missile defence systems await future consideration ‘as technology matures’.

The NDS and IIP policy platform and investment priorities indicated an almost complete absence of prioritisation of funding for GBAD over the coming decade. This, however, stood in contrast to a couple of other significant developments in 2024 that point to inconsistencies in the Australian Government’s approach to IAMD.

At the 2024 Australia-United States 2+2 Ministerial meeting (AUSMIN), the two countries signed a Statement of Intent on Integrated Air and Missile Defense committing to deliver “near-, mid-, and long-term opportunities for co-development, co-production, and co-sustainment of Integrated Air and Missile Defense (IAMD) capabilities.”108 In March 2024, the RAAF and the RAN provided support to the United States in carrying out an integrated air and missile defence test off the coast of Hawaii, involving the interception of a medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM). Defence noted that “During the test, Australia demonstrated its advanced radar capabilities aboard a Navy vessel, HMAS Stuart, while a RAAF E-7 Wedgetail assisted in data collection and communications.”109 Later that year, in October, Australia signed a A$7 billion agreement with the United States to acquire state-of-the-art long-range missiles, including SM-2 IIIC and SM-6 missiles, for the RAN, thereby boosting naval air and missile defence capabilities, including ballistic missile defence.110 What is clear, though, from these initiatives and the 2024 NDS and IIP, is that the ADF is over-reliant on Air Force and Navy capabilities for IAMD, with land-based systems being almost entirely absent from these developments.

The final pieces of the Albanese government’s 2024 spread of Defence policy documents were the DIDS and the GWEO Plan. The DIDS identified six strategic policy areas, including SDIP 4 — Domestic manufacture of guided weapons, explosive ordnance and munitions. This outlines a policy priority on “the pathway for domestic manufacturing of guided weapons will likely commence with local assembly of imported components and materials” and the “production of explosives and propellants.”111 In addition, the DIDS prioritises the “MRO&U (maintenance, repair, overhaul and upgrade) of priority munitions in Australia, with an initial focus on MK48 heavyweight torpedoes and Standard Missile-2 missiles.”112 This provides Australia with a foundation priority for the sustainment and manufacture of missiles.