Executive summary

Australia has long struggled to establish and sustain an effective force posture in its strategically critical northwest approaches and the broader Indian Ocean, despite the region’s growing importance amid rising strategic competition. To ensure credible operational readiness and meet emerging security challenges, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) must increase investment, resources and political attention toward Western Australia and ADF forward bases across the Indian Ocean region.

Changes to the ADF’s defence posture are not keeping pace with an Indian Ocean that is becoming a key focal point for intensifying strategic competition.

This brief analyses the trajectory of Australia’s regional engagement over the past five decades, examining how Western Australia and the broader Indian Ocean has featured in Canberra’s strategic thinking and subsequently shaped its force posture efforts. While successive Australian governments have increasingly recognised Western Australia and the Indian Ocean as of strategic significance to Australia’s security fortunes, changes to the ADF’s defence posture are not keeping pace with an Indian Ocean that is becoming a key focal point for intensifying strategic competition.

In order for Australia to effectively address the security challenges and seize the strategic opportunities presented by the Indian Ocean region, this policy brief offers recommendations that reinforce Australia’s defence and strategic posture in Western Australia and its littoral forward base network. These include:

- Implement overdue commitments from the 2012 Force Posture Review regarding Australia’s Indian Ocean coastline.

- Empower the Assistant Defence Minister to prioritise the Northern Base Network through the Defence Estate Review process.

- Elevate defence planning for the northeast Indian Ocean, factoring in shifting regional power dynamics, Western Australia’s proximity to East Asia and the region’s significance for US-Australia posture cooperation.

- Align infrastructure development across the Northern Base Network with the objectives of the 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) to ensure the ADF can conduct sustained operations from these bases.

- Fast-track base upgrades and posture initiatives at Cocos (Keeling) Islands and North Western Australia, utilising funds freed up from the 2023 Defence Estate Audit.

- Expand ADF training and exercise programs in North Western Australia to strengthen readiness and interoperability.

- Develop Western Australia as a testing and evaluation hub, capitalising on its expansive air, land and maritime domains.

- Align Australia’s force posture initiatives with allies and partners to maximise the impact of Australia’s enhanced regional defence presence.

Introduction

In 2023, the Albanese government tasked a Defence Strategic Review (DSR), led by two Independent Leads, Professor the Hon Stephen Smith and Air Chief Marshal (rtd) Sir Angus Houston, to assess the political and material factors of Australia’s defence strategy. The approach taken by the Independent Leads was to initially focus on assessing the political factors of strategy: assessing the problems that Australia faces in its strategic environment,1 interrogating their broader context and assessing the “goals, resources and policies” that were required to address them.2 The DSR subsequently recommended that the Albanese government formally adopt a regional balancing strategy for the Indo-Pacific, enabled through collective deterrence in the region; deterrence by denial at the national level; and a focus for the Australian Defence Force (ADF) on a military strategy of denial.3 This approach was codified through the concept of ‘National Defence’ — a “unifying national strategic approach” that is both “whole-of-government” and “whole-of-nation.”4 Given the scale of the problems and the threats that Australia faces, this approach was not something, as the DSR explicitly noted, the Department of Defence could “grapple with alone.”5 As such, it emphasised supporting concepts such as “integrated statecraft” and “national resilience.”6

With the political elements of strategy in place, the focus of the DSR’s Independent Leads then turned to more material factors of strategy.7 Specifically, the DSR’s ‘Terms of Reference for the Independent Leads of the Review’ focused heavily on the material factors of strategy. It directly tasked the Independent Leads to undertake “a holistic consideration of Australia's Defence Force structure and posture by including force disposition, preparedness, strategy and associated investments.”8 The focus of force posture in the review was particularly specific. According to the DSR’s Glossary of Terms, Force Posture:

Encompasses where the Australian Defence Force's units, facilities, and support elements are located, the capabilities (equipment and the force structure) that can be deployed at short notice, the quality of training facilities and bases, the ability of our personnel to sustain high-tempo operations and our connectedness with partners, allies and industry to achieve intended objectives during war and peace. This includes the estate and infrastructure elements of the Defence Integrated Investment Plan.9

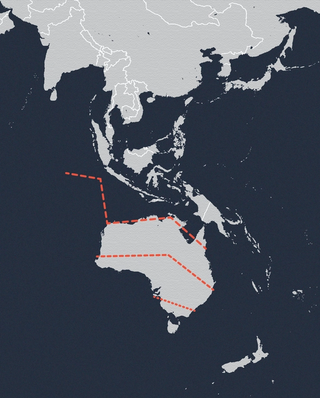

Australia's northwest approaches

The DSR placed renewed focus on the strategic significance of Australia’s northwest approaches, long viewed by Australian defence planners as a vulnerability to adversary exploitation due to their geographic isolation and relatively sparse population: a perception shaped by the Japanese attacks on Darwin and other northern bases during the Second World War.10 While conscious of these concerns, the DSR also underlined the strategic opportunities that these areas offered to Australia’s strategic fortunes. Positioned at the maritime junction of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, northern and western Australia were identified, as Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles coined, critical platforms for “impactful projection” into the broader region and enabling the ADF to “hold an adversary at risk further from [Australia’s] shores”.11 As a result of the northwest approaches, the review reconceived the geographic lens of Australian strategy to focus on a primary area of military interest (PAMI) that encompasses the northwest Indian Ocean, maritime Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. This arc focuses on Australia’s northern approaches and its relative geography to East Asia, placing a strong emphasis on the eastern Indian Ocean and Australia’s Indian Ocean territories and coastline.

This emphasis was followed through in Australia’s 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS), where the government codified the recommendations of the 2023 DSR into policy.12 The NDS committed to deepening defence relationships with countries in the Indian Ocean, with a particular focus on strengthening Australia’s relationships with Sri Lanka, the Maldives and Bangladesh. The NDS also identified India as a “top-tier” security partner for Australia.13 As such, Australia’s interest in security cooperation in this region has considerably surged in recent years. Beyond long-term shared strategic interests in ensuring peace and stability in Indian Ocean waterways, the immediate priorities for Australian defence partnerships include deepening defence industrial cooperation; improving maritime search and rescue capability; countering transnational crime, terrorism, and piracy; addressing people smuggling and other human security risks; and responding to natural disasters.14

The Australian Department of Defence’s (hereafter, Defence) mechanism to enhance this engagement came in the form of the Defence Cooperation Program (DCP).15 The DCP supports regional countries in developing their own defence capacities through a range of training initiatives and bilateral exercises, capacity building initiatives, and equipment and infrastructure projects. In recent years, the DCP has made important progress in the Pacific and Southeast Asia. The program’s inclusion of the northeast Indian Ocean provides an opportunity to link emerging efforts there with existing measures in Southeast Asia, as well as to enhance many of Australia’s bilateral and minilateral engagements with Southeast Asian partners on Indian Ocean region-related issues and developments. Most recently, the Australian Government’s announcement in June 2025 that it would gift a Guardian-class Patrol Boat to the Maldives is a significant step in developing its partnerships and engagement in the Indian Ocean region, having learnt from the DCP’s similar accomplishments in the Pacific and recognition of the critical role that smaller states play in securing maritime security.16

The greatest challenge for Australia, however, is resourcing this capability uplift and delivering the required infrastructure and force posture to ensure a more sustained presence in and beyond Australia’s territorial waters.

In terms of hard power, Australia’s all-domain maritime capability in the northeastern Indian Ocean has grown considerably. The AUKUS partnership to deliver nuclear-powered submarine capability to Australia, along with related infrastructure and sustainment facilities at HMAS Stirling in Western Australia, are central to the ADF’s future presence in the northeast Indian Ocean and Australia’s broader contribution to maintaining a favourable regional strategic balance. More immediately, concurrent modernisation efforts are underway in Australia’s force posture that will equip the ADF to undertake more effective and ambitious operations in the Indian Ocean in the future. The Albanese government has committed A$11.1 billion over the decade to expanding the naval fleet, including doubling the number of major surface combatants.17 Programs are also underway to improve infrastructure on Cocos (Keeling) Island, as well as other key locations across the northwest of Australia, to better support maritime surveillance operations by P-8A Poseidon aircraft.18 The greatest challenge for Australia, however, is resourcing this capability uplift and delivering the required infrastructure and force posture to ensure a more sustained presence in and beyond Australia’s territorial waters. Compounded by Australia’s emphasis on the Northeast Indian Ocean and developing its relationship with India in particular, the Southern Indian Ocean has emerged as a less developed aspect of Australia’s defence strategy.19

Force posture in Western Australia: From Dibb to the DSR

The development of Australia's post-Vietnam force posture initiatives in Western Australia has, in recent decades, been a tale of lost opportunities. The original developments occurred from the late 1960s to the early 1980s as the Department of Defence shifted focus to a more self-reliant defence of Australia. The first of the ADF’s ‘bare bases’ — forward operating bases located in remote areas and designed for rapid activation during wartime or exercises — were established at Tindal and Exmouth in the early 1970s, and HMAS Stirling in Western Australia was established in 1978.20 During the 1980s, and following on from the 1986 Review of Australia’s Defence Capabilities (known as the Dibb Review), HMAS Stirling became the main submarine base; the Army’s presence in northern Australia was enhanced; RAAF Base Tindal in the Northern Territory was established as a permanent forward base, and an additional bare base was added with RAAF base Scherger in Cape York Peninsula, Queensland. Progress on these facilities was limited, given the limited threat Australia faced at the time. 21

With an increasing focus on major power competition in the region and as a precursor to the 2013 Defence White Paper, which introduced the ‘Indo-Pacific’ as a strategic framework to Australia's defence planning, then Minister for Defence, The Hon Stephen Smith, commissioned a Force Posture Review in 2011. This review, conducted by two former defence secretaries, Allan Hawke and Ric Smith, was released in 2012. This review highlighted the:

limitations to the capacities of the ADF bases, facilities and training areas, particularly in Australia’s North and West and our ability to sustain high tempo operations in Northern Australia and our approaches, the immediate neighbourhood and the wider Asia-Pacific region.22

The Hawke-Smith review included a range of recommendations to enhance force posture in Western Australia. To strengthen Australia's northern and western defence posture, the review recommended the ADF to prioritise upgrades to key air and naval facilities. This includes enabling sustained operations of KC-30 and P-8 aircraft from RAAF Learmonth, enhancing the Cocos (Keeling) Islands airfield for UAV and limited tanker use, and improving infrastructure at Curtin and Learmonth to accommodate future combat aircraft. They recommended additional investment for Broome as a forward operating base, while Fleet Base West required expanded wharf and support capacity to host major surface combatants, aircraft carriers, and submarines, including those of the US Navy, supporting broader Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia deployments. The ADF was recommended to deepen operational readiness in Northwest Australia through increased joint and simulated exercises, frequent aircraft and ship visits and senior leadership study programs. These efforts should be supported by improved communication about ADF presence and activities in the region. To ensure resilience during high-tempo operations, the Hawke-Smith review recommended that Defence assess fuel, munitions, and logistics requirements at forward bases, implement physical hardening, and enhance base repair and missile support capabilities.23

The 2012 Force Posture Review recommendations were included in the 2013 Defence White Paper and budget planning. However, the Gillard-Rudd government’s loss in the 2013 election led to most of the 2012 Force Posture Review’s recommendations being shelved by the new Abbott Coalition government. The outcomes of the 2012 Force Posture Review were revisited during the 2023 Defence Strategic Review and reassessed in light of the worsening strategic situation. The DSR noted that “Most of those recommendations relating to the northern bases have not been implemented… Irrespective of this history, it is now imperative that our network of northern bases is urgently and comprehensively remediated.”24

Subsequently, the 2023 DSR outlined a framework of three layers of defence bases and infrastructure that includes “a network of fully enabled northern operational bases, a series of bases in depth to support the Defence enterprise and identification of relevant Civil infrastructure for Defence needs.”25 This framework includes the development of the:

key line of forward deployment for the ADF stretches across Australia’s northern maritime approaches. Integral to this sovereign Australian posture is the network of bases, ports and barracks stretching in Australian territory from Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the northwest, through RAAF bases Learmonth, Curtin, Darwin, Tindal, Scherger and Townsville.26

As the Indian Ocean’s geopolitical importance continues to rise, Australia’s vast and strategically advantageous geography supports the need for multiple operational lines of deployment.27 As such, a distributed network of well-established bases and facilities across the country provides the “strategic depth” necessary to integrate and sustain defence capabilities in order to maintain a credible deterrent and conduct military operations if required.

The DSR outlines this concept through three distinct operational and support lines:

- Forward Line of Deployment: This primary arc stretches from Cocos (Keeling) Islands through RAAF Base Learmonth in Exmouth (2,140 km), to Darwin and Tindal (including RAAF Base Curtin, 2,000 km), then to Weipa (RAAF Base Scherger, 1,230 km), and finally to Townsville (904 km).

- Operational Support Line: This secondary axis runs from Perth to Alice Springs (2,000 km), then across to Brisbane (2,000 km), forming a central spine of logistical and operational support.

- Industrial and Strategic Depth Line: The third line connects Adelaide to Sydney (1,200 km), covering the densely populated southeast corridor — home to most of the nation’s defence industry, training facilities, headquarters, and broader economic infrastructure.28

The DSR called for a range of measures to increase Australia’s force posture and defence preparedness across the frontline Northern Base Network, a number of bases, ports and barracks stretching across or adjacent to Australia’s northwest approaches.29 It noted that “Defence infrastructure must provide a hardened and dispersed platform to support the deployment of the ADF and the defence of Australian territory and our interests.”30 Additionally, “[t]he priority for this network is the series of critical air bases. This series of northern air bases must now be viewed as a holistic capability system and managed as such by the Chief of Air Force.” The review stated that there must be immediate and comprehensive work on these air bases undertaken in hardening and dispersal; runway and apron capacity; fuel storage and supply; aviation fuel supply and storage; GWEO storage; connectivity required to enable essential mission planning activities; accommodation and life support; and security.”31

Subsequently, the Albanese government agreed, in principle, with these recommendations. These force posture provisions were followed up in the 2024 NDS chapter on ‘Defence Force Structure, Posture and Bases’, noting that “Defence must posture to enable the impactful projection of military effects from Australia to project and sustain a deployed force and to drive efficient use of training areas. Defence’s domestic force posture is to:

- Deliver a logistically networked and resilient set of bases, predominantly across the north of Australia, to enhance force projection and improve Defence’s ability to recover from an attack.

- Increase protection of bases and provide the ability to withstand disruption in crisis or conflict.”32

The NDS also included a commitment in the 2024 Integrated Investment Program to advance the implementation of the Australian Government’s six immediate priorities announced in response to the Defence Strategic Review. This includes: “improving the ADF’s ability to operate from Australia’s northern bases…to ensure the ADF can project deployed forces and continue to operate through disruption.”33

The Cocos-Keeling Islands and the Gascoyne Gateway

While the measures previously outlined offer clear priorities, implementation has proven to be challenging. The delay in upgrading the Cocos-Keeling Islands between the Force Posture Review in 2012 and the DSR in 2023 was considerable. This had a significant financial impact, particularly with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, economic disruption, supply chain shortages and workforce shortages. More recently, it has been reported that part of the upgrades, which were initially costed at A$184m, were reported in a 2022 parliamentary committee to have tripled to A$568m, resulting in a A$384m cost blowout.34 Additionally, the project has exceeded its deadline. According to Defence, construction on the island commenced in late 2024, with all works forecast to be complete by early 2028, rather than the original 2026 deadline.35

The importance of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands to military operations in the Indian Ocean is underscored by a May 2024 US Naval Facilities Engineering Command project seeking proposals for new facilities, repairs, renovations and infrastructure, worth a combined US$15 billion.36 To be funded from the US Pacific Deterrence Initiative, it included a focused reference to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands (along with the Philippines, Timor Leste and Papua New Guinea). According to former senior Australian defence official Ross Babbage, the United States has shown an interest in P-8 Poseidon planes, E-7 Wedgetail early warning aircraft, aerial refuelers and UAVs to operate from the island.37 The ADF has also indicated that it intends to operate its electronic warfare and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft, the MC-55A Peregrine fleet, from the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, with the first aircraft available for operations within the next 12 months.38