Executive summary

Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine has catalysed growing strategic alignment between the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and its four key Indo-Pacific partners, Australia, South Korea, Japan and New Zealand. While all agree that Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific strategic dynamics are deeply “interconnected,” political alignment has not yet translated into an effective and fully operationalised security partnership. This is particularly pertinent as US support for transregional initiatives has waned under the second Donald Trump administration. To address the gap between declarations of intent and effective operationalisation of the NATO-IP4 security partnership, the United States Studies Centre and the Korea Foundation convened the inaugural ‘Indo-Pacific Security Dialogue’ in August 2025, inviting leading experts from Europe and the Indo-Pacific to participate in closed-door discussions on the most pressing challenges and opportunities currently facing transregional security cooperation. Those discussions informed the following recommendations for strengthening NATO-IP4 cooperation:

- Approach the NATO-IP4 partnership as a complement to — not a substitute for — existing US security cooperation commitments in the two theatres.

- Keep NATO-IP4 security cooperation focused on shared, hard-security issues that align with NATO’s established mandate.

- Develop deeper coordination mechanisms among the IP4 countries to help develop a collective IP4 agenda, clarify IP4 expectations about NATO’s future role in the Indo-Pacific, and ultimately work to marshal tangible security cooperation outputs.

- Establish common understandings of deterrence and consider using the United Nations Command on the Korean Peninsula as an existing framework to deepen non-US Euro-Atlantic partners’ roles in sustaining Indo-Pacific deterrence, should NATO and the IP4 solicit it.

- Expand IP4 engagement with NATO’s Centres of Excellence and consider establishing Indo-Pacific-based counterparts to enhance regional deterrence.

- Map NATO and IP4 defence industrial ecosystems to identify industrial strengths and capabilities that can be leveraged to meet immediate strategic requirements and help resource a credible deterrence posture in both theatres over the long term.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing strategic alignment between the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and its four key Indo-Pacific partners — Australia, South Korea, Japan and New Zealand — also known as the IP4. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Europe’s growing awareness of the security challenge posed by China and the Indo-Pacific’s emergence as the focal point of US-China strategic competition have all reinforced the reality that security developments in one ‘theatre’ seldom remain confined to it.1 As South Korea’s Foreign Minister Cho Hyun encapsulated during the United States Studies Centre (USSC) and Korea Foundation’s inaugural Indo-Pacific Security Dialogue in August 2025: “instability in one region never stays contained. It reverberates across borders in profound and sometimes unpredictable ways. The security of the Indo-Pacific is now closely linked with that of the Euro-Atlantic.”2 The emergence of the IP4, first convened at the NATO Summit in Madrid in June 2022, reflects this sentiment and the intent to develop more sophisticated forms of trans-Atlantic-Pacific security cooperation.

“Instability in one region never stays contained. It reverberates across borders in profound and sometimes unpredictable ways. The security of the Indo-Pacific is now closely linked with that of the Euro-Atlantic.”

NATO and the IP4 have achieved important milestones to this end. Since 2022, the IP4 have participated in every major NATO Summit, a symbolic marker of their growing relevance to transatlantic security debates. These summits, and other high-level ministerial and ambassadorial meetings, have created new habits of dialogue and encouraged NATO and IP4 governments to account for the indivisibility of Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific strategic dynamics in their respective national and regional security decision-making processes. Indeed, in the past seven years, Euro-Atlantic partners and organisations such as Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the European Union have all released Indo-Pacific strategies that underscore the importance of working with like-minded partners in Asia to bolster their own defence and economic security prospects.3 Given the increasingly “inseparable” nature of security dynamics between the two theatres, leaders in Canberra, Seoul, Tokyo and Wellington have assumed more prominent roles in shaping Europe’s security order.4 Their engagement reflects growing concerns that, in the cautionary words of former Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, “Ukraine may be the East Asia of tomorrow.”

As a result, the IP4 countries have played an instrumental part in the international coalition supporting Ukraine. Japan is estimated to have sent more bilateral economic and humanitarian aid to Ukraine than Finland, France or Poland.5 South Korea’s decision to indirectly provide Kyiv with hundreds of thousands of much-needed artillery shells, via the United States, offered a more significant contribution to Ukraine’s defence than what a number of European states, constrained by years of post-Cold War defence spending retrenchment, were initially able or willing to offer.6 Meanwhile, Australia has provided A$1.5 billion in assistance and delivered almost 50 M1A1 Abrams tanks to add to the mobility and firepower of Ukraine’s armed forces on the battlefield.7 New Zealand and Australia also participate in the NATO Security Assistance and Training for Ukraine (NSATU) command in Germany, which coordinates training of Ukrainian forces, as well as the supply and repair of military equipment for Ukraine.8 This has set a precedent for deeper consultation and inclusion in discussions shaping partners’ security architectures on both sides of Eurasia.

Despite these notable developments, the NATO-IP4 partnership has struggled to move beyond its predominantly dialogue-centric focus. While enhanced consultations have proved valuable, they remain inadequate in responding to the interregional security dynamics driving the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic’s deteriorating strategic environments alone.9 Additionally, the IP4 countries’ support for Ukraine has largely occurred on an ad-hoc basis, remaining subject to domestic political headwinds and the demands of other competing defence priorities and in-theatre stockpile readiness levels.

By contrast, Russia, China, Iran and North Korea have made notable progress on operationalising their own cooperation to reshape the international rules-based order. This includes enabling Russia to sustain its war effort against Ukraine, actively expanding defence technology cooperation efforts, aligning and amplifying each other’s narratives on important global political and security issues, and deepening or newly formalising bilateral ties to achieve sophisticated strategic effects.10 According to historian Hal Brands, the level of strategic coordination among the developing China-Russia-Iran-North Korea security axis already exceeds what the Axis Powers were able to achieve during the 1930s and the Second World War.11 If the NATO-IP4 partnership hopes to turn its recently enhanced dialogue into sustained security cooperation outputs, the current scale and pace towards operationalisation remain insufficient to meet the growing challenges posed by a more unified theatre of strategic competition in Eurasia.

If the NATO-IP4 partnership hopes to turn its recently enhanced dialogue into sustained security cooperation outputs, the current scale and pace towards operationalisation remain insufficient to meet the growing challenges posed by a more unified theatre of strategic competition in Eurasia.

Against this backdrop, the USSC and the Korea Foundation co-hosted the inaugural ‘Indo-Pacific Security Dialogue’ in Sydney in late August 2025. The dialogue brought together more than fifty leading experts, policymakers, diplomatic and defence industry representatives from the IP4 countries and NATO member states to examine how the trans-Atlantic-Pacific security partnership can advance and operationalise security cooperation in the face of escalating shared challenges. This is particularly relevant as US efforts to further transregional security cooperation among its Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic allies and partners have waned under the second Trump administration. Indeed, the much-covered absence of three IP4 heads of state from the most recent NATO Summit in The Hague in June 2025 has raised questions among some observers about the level of enthusiasm among IP4 leaders to seriously engage with the NATO-IP4 framework without strong US encouragement.12 At the same time, many NATO and IP4 countries are having to navigate new demands from Washington to significantly increase burden sharing, including defence spending, as well as provide clarity on specific roles and missions that allies might undertake in potential regional contingencies. Put together, these dynamics underscore a growing array of challenges facing NATO and the IP4, where enhanced spoke-to-spoke dialogue, greater coordination and practical cooperation to address such issues are now more important than ever.

The following findings and policy recommendations draw on the insights and recommendations generated from the inaugural Indo-Pacific Security Dialogue, held under the Chatham House Rule, to identify the most pressing challenges and areas of opportunity for NATO and the IP4 countries in effectively operationalising growing trans-Atlantic-Pacific security alignment to generate impactful strategic effects across both theatres.

Dialogue findings

1. Shared values and interests have underpinned NATO-IP4 security cooperation, yet diverging security priorities and varying risk appetites have limited opportunities to operationalise the partnership.

Shared values and interests have underpinned NATO-IP4 security cooperation, yet diverging security priorities and varying risk appetites have limited opportunities to operationalise the partnership.

Though NATO maintains relationships with 35 non-member countries and a range of international organisations, Australia, South Korea, Japan and New Zealand have emerged as the most cohesive grouping for NATO’s engagement with the Indo-Pacific.13 Their political and ideological compatibility, anchored in possessing advanced economies, democratic institutions and a shared commitment to the rule of law, has made closer transregional security cooperation a seemingly natural and logical development. As longstanding allies of the United States, the IP4 countries and NATO member states also share a deep interest in preserving the regional and global rules-based order on which their security and economic prosperity depend. As a result, security ties between NATO and IP4 countries have benefited from a rich history of regular interactions since the 1990s and early 2000s. Transregional security ties have strengthened more recently through the establishment of goal-orientated frameworks that coordinates NATO’s collaboration with a single partner, known as NATO’s Individually Tailored Partnership Programmes (ITPPs). The ITPPs have provided a more structured foundation for strengthening interoperability, information exchange and coordination on an array of non-geographically bound challenges (see Figure 1). The rapidly evolving security environments in both theatres have only accelerated these transregional linkages, most notably since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Figure 1. Timeline of key developments between NATO and IP4 countries (1990s–2025)14

However, despite a shared commitment to liberal democratic principles and the international rules-based order, NATO and the IP4 countries have yet to convert growing political alignment into an effective transregional security partnership. Dialogue participants underscored how divergent national priorities, distinct regional threat environments and uneven political bandwidth across the two groupings continue to stunt progress towards the partnership’s operationalisation, including among the IP4 countries.

Among the IP4’s Northeast Asian nations, structural pressures continue to constrain strategic attention and defence resources. North Korea’s accelerating nuclear and missile programs and the strategic challenges posed by China’s rapid emergence as a credible peer-competitor consume Tokyo and Seoul’s defence planning and ability to invest political attention and sustained resources to security initiatives involving Euro-Atlantic partners. However, within this common strategic setting, South Korea and Japan diverge in how they approach NATO in addressing such challenges, reflecting the transatlantic alliance’s position within each country’s hierarchies of strategic partnerships and their differing threat perceptions.

Divergent national priorities, distinct regional threat environments and uneven political bandwidth across the two groupings continue to stunt progress towards the partnership’s operationalisation.

South Korean dialogue participants noted that prior to 2022, Seoul’s engagement with NATO was comparatively limited and largely centred on peninsula-related security issues.15 References to NATO in South Korean defence documents were typically brief and, even after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, Seoul underlined the continuing importance of maintaining security ties with Moscow to help support its broader North Korea policy objectives.16 South Korea’s risk tolerance regarding China has also created another challenge for its engagement with NATO. Seoul has sought to avoid antagonising Beijing, especially after experiencing economic retaliation and a diplomatic freeze following the 2016 Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) deployment, which cost US$15.6 billion in tourism revenue alone.17 Although President Lee Jae Myung has acknowledged the shrinking viability of South Korea’s traditional dual-track policy of “economy with China, security with the United States,” deepening security cooperation with NATO still risks provoking renewed tensions with Beijing.18 As such, the Yoon Suk Yeol administration’s (2022-2025) efforts to elevate cooperation with NATO on global security issues stand out more as a deviation from, rather than a redefinition of, Seoul’s traditional strategic calculus with respect to Euro-Atlantic security partnerships. Early indications from the Lee administration’s emerging “pragmatic” foreign policy doctrine suggest a desire to stabilise relations with countries such as Russia and China, which may in turn lead Seoul to take a more selective approach to security engagement with NATO out of concern for how it could affect this agenda.19

By comparison, dialogue participants identified Japan as the most proactive and enthusiastic IP4 partner seeking to deepen security cooperation efforts with NATO, and transregional cooperation more broadly. Since the 2013 Joint Political Declaration and the 2014 Initial Individual Partnership and Cooperation Programme (IPCP), Tokyo has steadily cultivated momentum in its relationship with NATO.20 Successive updates to the Japan-NATO IPCP in 2018 and 2020 expanded cooperation from political consultation to practical defence activities, including enhancing interoperability and joint exercises in the Indo-Pacific.21 More recently, in April 2025, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte visited Japan to discuss Japanese participation in NSATU and met with Japanese defence industry representatives to clarify “what they do to ramp up production and how we can better work together” to take the NATO–Japan partnership to the “next level.” Given Japan’s constitutional constraints and NATO’s North Atlantic-focused security mandate, cooperation in areas such as defence industrial collaboration has emerged as a promising vector for expanding bilateral ties, as it tends to attract comparatively little domestic pushback.22

For Australia and New Zealand, interest in broadening strategic engagement with like-minded partners has also grown, but similar issues surrounding geographic and capability constraints have meant these efforts are more visible in the Indo-Pacific than with Euro-Atlantic partners. In Australia’s case, intra-regional security engagements have markedly been on the uptick in the last ten years. Australia established a Comprehensive Security Partnership (CSP) with South Korea in 2021 and, building on its 2014 CSP with Japan, developed the Australia-Japan Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) in 2022, enabling more frequent and flexible access to each other’s defence facilities and ensuring Australia has a more direct role in Northeast Asia’s security dynamics.23 Additionally, Australia’s threat perception has meant it has been more willing to strategically align proactively with the United States, despite temporarily suffering tariffs and bans on barley, wine, coal and beef in 2020 by China.24

This should not downplay Australia’s record as the longest serving IP4 country cooperating with NATO on shared security issues. Its practical cooperation with NATO dates back to 1953, when Australia became the first partner nation to participate in Exercise Coronet, a physical demonstration of NATO air power at a time of Soviet expansion in Europe.25 Among others, Australia has been an important contributor to NATO-led operations, including ISAF in Iraq (2003–2014), the Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan (2015–2021) and Operation Sea Guardian in the Mediterranean (2022-present).26 In the last five years, Australia has also established new CSPs with Denmark and Germany, and is exploring a Security and Defence Partnership with the European Union.27

However, recent government statements and strategic documents, including the 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) and 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS), have underlined that Australia’s primary operational focus lies in its more immediate subregions — or “near approaches” — encompassing the Eastern Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia and the South Pacific.28 Australian dialogue participants noted that these subregions are where Australia’s finite security assets are best positioned to deliver meaningful strategic effects, as well as helping support its broader “strategy of denial,” which aims to deter an adversary’s power projection against Australia and concurrently afford Canberra a favourable surrounding regional strategic balance.29

By comparison, New Zealand’s strategic posture reflects its modest but gradually expanding defence capabilities and deep economic integration with Asia. Wellington recognises the threat of rising strategic volatility in the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic theatres to its own security. New Zealand is increasingly aligning with like-minded partners in expressing concern about coercive behaviour and challenges to the rules-based order, including the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) circumnavigation of Australia and lack of sufficient notification for the PLAN’s live-fire exercises in the Tasman Sea in February 2025.30 Recent examples underscoring New Zealand’s growing regional security engagement ambitions include joining South Korea’s small cadre of CSP members in October 2025, its commitment to lifting defence spending to 2% of GDP in the next eight years and having the only IP4 head of state to attend the 2025 NATO Summit in The Hague.31 For a nation of five million people and with a long tradition of aversion toward formal security alignments, these steps are themselves no small achievement. Nonetheless, structural constraints and domestic political bandwidth continue to limit Wellington’s ability to scale up its security engagement. New Zealand’s finite defence resources, trade dependency on China, and enduring operational focus on the South Pacific, especially on non-traditional security efforts such as climate security, limit its ability for sustained hard-security cooperation beyond its immediate subregions. As a result, New Zealand’s defence engagement efforts remain less developed than those of its IP4 counterparts, both within the Indo-Pacific and with NATO.

If properly managed, these divergences can help clarify complementary roles, identify realistic pathways for collaboration and ultimately strengthen the foundations for an operationalised NATO-IP4 partnership.

Taken together, the national constraints and divergent strategic priorities of Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand continue to shape, and in many cases limit, the practical boundaries of the NATO-IP4 relationship. Despite broadly shared assessments of the strategic environment, each country engages NATO from a different vantage point, informed by its own domestic political context, regional threat perceptions and alliance commitments to the United States. As a result, the IP4 possess varying expectations about the role Euro-Atlantic partners can or should play in the Indo-Pacific. These mismatched conceptualisations have slowed progress toward a more consistent operational security partnership and have impeded the four Indo-Pacific countries’ ability to articulate a more coherent and collectivised IP4 agenda.

However, several dialogue participants emphasised that awareness among NATO and the IP4 of the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theatres’ strategic challenges has reached a level of maturity that enables more purposeful cooperation. All four Indo-Pacific partners increasingly recognise that they face a widening set of shared threats that no single state can manage alone. In this context, differences in perspective should be understood less as obstacles and more as starting points for structured coordination. If properly managed, these divergences can help clarify complementary roles, identify realistic pathways for collaboration and ultimately strengthen the foundations for an operationalised NATO-IP4 partnership.

2. Dialogue participants identified growing strategic coordination between China, Russia, Iran and North Korea as the primary driver for the recent growth in NATO-IP4 security ties.

Dialogue participants identified growing strategic coordination between China, Russia, Iran and North Korea as the main driver behind the recent convergence among US allies and partners across the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic. Deepening security cooperation among these powers has heightened allied concerns about a more interconnected cross-theatre challenge to the international rules-based order. Russia’s war against Ukraine, in particular, has demonstrated how this network of revisionist states is reshaping the global security environment and testing the resilience of US and allied partnerships and deterrence mechanisms in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific.

Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, North Korea has supplied a growing stockpile of artillery, ammunition and an estimated 15,000 troops to Russia’s war effort, marking Pyongyang’s largest combat deployment since the Korean War.32 For NATO members, North Korea’s support to Russia has proven crucial in allowing Moscow to prolong the conflict, with South Korean military sources estimating that Pyongyang now provides around 40% of Russia’s ammunition.33 For South Korea, the United States and their partners, Russia’s growing security ties with North Korea are consequential because they provide Pyongyang with critical defence materials and diplomatic cover, emboldening its military modernisation and potentially raising North Korea’s willingness to test the limits of US and South Korean deterrence efforts and alliance cohesion on the Korean Peninsula. It could even propagate a shift in North Korea’s foreign policy outlook, enhancing its sense of agency in influencing regional and global strategic dynamics, which, if realised, would deliver significant repercussions for other IP4 and NATO countries’ strategic interests over the long term.

Unlike North Korea, China has refrained from overtly supplying Russia with lethal aid. However, Beijing’s contributions to the war effort have been no less critical. Despite claiming neutrality, China has supplied Russia with vital commercial and dual-use goods that are directly sustaining Moscow’s military operations. Since Russia’s invasion, Beijing has dramatically increased exports of “high-priority items,” which include 50 dual-use products such as semiconductors, telecommunications gear, machine tools, radars and sensors.34 These items are essential for Russia’s military-industrial base, which lacks the domestic capacity to produce them at sufficient scale. Chinese exports have proved decisive. Advanced Chinese machinery helped triple Russia’s production of Iskander-M ballistic missiles between 2023 and 2024. In 2024 alone, China supplied 70% of Russia’s imports of ammonium perchlorate, a key ballistic missile propellant.35 Tehran has also supplied drones, technologies and financing to Russia’s war economy, while North Korean workers reportedly staff Russian drone plants using Iranian designs and Chinese equipment.36 US and European officials have warned that Pyongyang could also channel arms to Russia via Iran, recalling the covert transfer mechanisms China employed to arm Iran via third countries, such as Bolivia and Pakistan, in the 1980s.37

To be sure, security cooperation among these revisionist states has been prosecuted unevenly, with some relationships within the security axis exhibiting more frequent or sophisticated forms of activity over others. For example, the relatively muted response from Russia and China to the US strike on Iranian nuclear facilities in June 2025 exposed vulnerabilities in the bloc’s cohesiveness.38 By contrast, the bilateral relationship between Russia and China has been elevated since the establishment of their so-called “No Limits” partnership in early 2022.39 Moscow and Beijing have since conducted multiple strategic bomber exercises across the Pacific, as well as a growing number of joint submarine and surface vessel patrols off the coasts of South Korea, Japan, the United States, and even in the Mediterranean and Black Seas.40 These activities signal Moscow’s enduring strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific and the importance it attaches to its growing relationships with key regional partners like China and North Korea, despite the demands imposed on it by the war in Ukraine. In this sense, cooperative efforts between these revisionist states have largely been conducted bilaterally rather than as a cohesive whole, with Russia seemingly acting as the axis’ ‘military hub’ and China as its predominant ‘economic hub’.41

Revisionist states have managed to operationalise their security coordination despite possessing far weaker institutional, military and economic linkages than the transregional partnerships embedded within the US-led alliance system. This should serve as a warning that adversaries are not waiting for perfect conditions to act, and neither should NATO and the IP4.

Dialogue participants concluded that regardless of the axis’ evolving configuration, growing strategic coordination among these revisionist states already represents an unprecedented challenge to the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic’s strategic fortunes. Many dialogue participants underscored how greater China-Russia-North Korea strategic coordination, in particular, has heightened the risk of simultaneous or sequential conflicts occurring in the Indo-Pacific, Europe and elsewhere.42 This has increased the strategic imperative for closer NATO-IP4 coordination to help strengthen collective defence preparedness and uphold a more credible deterrence posture in their respective but interconnected theatres. Dialogue participants also argued that NATO and the IP4 countries should not bank on the revisionist security axis’ internal differences splitting them apart. Such a collapse would more likely occur after the grouping has achieved its strategic objectives, by which point it would be overwhelmingly more challenging for NATO and the IP4 countries to reverse such developments.

These lessons, however, are yet to be fully digested among the IP4 and NATO policymakers. Several dialogue participants diagnosed a pervasive lack of urgency relative to the scale of these growing interconnected challenges. Dialogue participants certainly welcomed the recent proliferation of NATO and IP4 countries’ strategic documents and official announcements underscoring the growing impact of revisionist states’ strategic alignment to global security. NATO’s 2022 “Strategic Concept,” for instance, explicitly acknowledges that China’s “stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge [NATO] interests, security and values,” and that its deepening strategic partnership with Russia “and their mutually reinforcing attempts to undercut the rules-based international order run counter to [NATO’s] values and interests.”43 In addition to IP4 support for Ukraine, senior Indo-Pacific defence officials, such as Australia’s Office of National Intelligence director-general Andrew Shearer, explicitly identified how these states are exploiting grey-zone warfare to “weaken cohesion within democracies…and between allies, and to make the world safer for authoritarianism.”44

Still, the current trajectory for operationalising trans-Atlantic-Pacific security cooperation appears to be waiting for the ‘right moment’ to act. Dialogue participants noted that these moves will only enable adversaries to consolidate their cooperative gains and continue to expand influence across multiple theatres. A number of dialogue participants also noted that these revisionist states have managed to operationalise their security coordination despite possessing far weaker institutional, military and economic linkages than the transregional partnerships embedded within the US-led alliance system.45 This should serve as a warning that adversaries are not waiting for perfect conditions to act, and neither should NATO and the IP4.

3. NATO’s Individual Tailored Partnership Programmes have strengthened security cooperation between Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific partners. However, their highly customised approach has made it harder to develop a unified IP4 security agenda with NATO.

Given differences in strategic priorities and threat perceptions amongst Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand — and, of course, the IP4’s only recent emergence — transregional security cooperation between NATO and its four Indo-Pacific partners has advanced most readily through the ITPPs. While the ITPPs reflect similar principles in terms of NATO and the IP4 countries’ commitments to upholding the rules-based order, some dialogue participants noted that their tailored design has consequently made it difficult to define a unified set of security issues around which the IP4 could collectively engage NATO.

Indeed, upon closer examination, the content and ambition of the ITPPs notably vary (see Table 1). Japan’s ITPP is the most expansive, mirroring Tokyo’s increasingly global security posture, its readiness to publicly condemn coercive behaviour by China and Russia and its pursuit of advancing defence-industrial interoperability.46 Australia’s agreement is similarly outward-looking but places particular emphasis on defence-industrial collaboration, hybrid threats and maritime security.47 South Korea’s ITPP, though encompassing an impressive 11 areas of cooperation, remains narrower, constrained by the more immediate security challenges posed by North Korea and political sensitivities surrounding its relationship with China.48 Although Seoul has increased cooperation with NATO on cyber security, emerging technologies and non-proliferation, its capacity to sustain broader regional or global commitments remains relatively limited.49 New Zealand’s ITPP is the least militarised, prioritising resilience, information integrity, climate security, sanctions coordination and emerging technology governance, reflecting Wellington’s preference for less sensitive and non-kinetic forms of cooperation.50

Table 1. Core features of NATO’s ITPPs with IP4 countries51

As a result, the ITPPs have enabled transregional security cooperation while simultaneously constraining the operationalisation of NATO-IP4 cooperation. Their tailored nature ensures flexibility, political feasibility and Indo-Pacific partners’ buy-in, but they also seemingly institutionalise asymmetric levels of ambition. Japan and Australia are positioned for deeper engagement with NATO across deterrence, hard security and advanced capability development. South Korea’s defence focus on the Korean Peninsula and New Zealand’s focus on governance and norms create structural limits on how far these partners can integrate into a common framework. Though certainly attractive on an individual national basis, the deepening of these bespoke pathways has reinforced distinct national trajectories over time within a NATO ecosystem rather than convergence, making it increasingly difficult to craft a coherent IP4-wide agenda. This is notable given clear areas of overlap in their respective ITPPs with NATO, particularly in non-geographically bound issues such as cyber security, emerging and disruptive technologies and countering disinformation and hybrid threats.

4. While the war in Ukraine has helped NATO’s European members to distil clear expectations of what they would like from Indo-Pacific partners’ security engagement, it remains unclear what the IP4 countries seek from NATO in the Indo-Pacific.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has provided Europe with a singular galvanising event through which to channel the IP4 countries’ cooperation. Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand have subsequently responded with material, political and humanitarian support to Ukraine, creating a focused and functional basis for advancing NATO-IP4 cooperation in the European theatre. However, the four Indo-Pacific countries’ expectations for NATO’s role in the Indo-Pacific theatre are far less coherent, lacking a unifying regional contingency or security challenge around which to discipline transregional security cooperation.

Some dialogue participants noted that European maritime deployments to the region were not the most useful forms of transregional cooperation, as they do not provide an annual rotational presence to uphold a credible deterrence, and would not be sustainable if the security situation in Europe substantially deteriorated. Some dialogue participants noted that non-US Euro-Atlantic contributions to Indo-Pacific deterrence would be better positioned by providing strategic “inputs” — the processes and structures that help Indo-Pacific partners generate, sustain, and adapt capabilities, such as defence-industrial capacity, supply-chain resilience and surge potential. This contrasts with providing deterrence “outputs,” understood as the operational employment of capabilities, such as European carrier strike group deployments or expanded force-posture and basing arrangements with Indo-Pacific partners to create a more direct Euro-Atlantic defence footprint in the region.

Indo-Pacific countries’ expectations for NATO’s role in the Indo-Pacific theatre are far less coherent, lacking a unifying regional contingency or security challenge around which to discipline transregional security cooperation.

Others emphasised that NATO rotations in the Indo-Pacific, including sensitive transits and freedom of navigation deployments, signal that Europe has a stake in the security of the region and would not remain a disinterested or neutral party in the event of hostilities. This signal can have important effects on adversaries’ thinking about the risks of conflict and therefore contribute to general deterrence in the region. As such, recent improvements in the sequencing of European maritime deployments to the Indo-Pacific, including those of France, Italy and the United Kingdom in 2025, are welcome steps.52

Still, NATO’s direct defence role in the Indo-Pacific is constrained by its North Atlantic–focused mandate and members’ competing priorities. While NATO acknowledges the Indo-Pacific’s growing relevance to Euro-Atlantic security and even China’s growing challenge to the alliance, internal divisions among NATO member state leaders have so far dampened the development of a more pronounced and coherent regional security role. For example, France has repeatedly argued against overextending NATO’s geographic scope, with French President Emmanuel Macron having blocked proposals to establish a NATO liaison office in Tokyo in 2023.53 It is also worth noting that several European powers, such as Germany, face structural economic constraints that limit their willingness to engage more deeply in Indo-Pacific security affairs. While Berlin’s dependence on Chinese imports of key raw materials, intermediate and final goods like electronics has forced it to confront these vulnerabilities, its decision to vote against EU tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles in October 2024 underscores that its greater priority is maintaining stable economic relations with Beijing. The latter may be put at risk if it supports an expanded NATO role in the Indo-Pacific.54 These divergent European perspectives leave Indo-Pacific partners with an incomplete picture of what NATO is willing or politically able to do.

5. Dialogue participants did not reach consensus on the institutional form or depth needed to advance NATO-IP4 cooperation, but many emphasised the need for improved coordination mechanisms among the IP4 countries.

At present, the NATO-IP4 format lacks meaningful institutionalisation, figuring more as a ‘NATO+4’ configuration than a formal engagement between coherent blocs. This means that while the four partners share broad strategic interests, the absence of codified mechanisms for coordination, either among the IP4 themselves or between the IP4 and NATO, has prevented more regular engagement and limited the partnership’s ability to deliver sustained security outputs. Views among dialogue participants varied on whether formalising the relationship would help overcome these shortcomings. Some participants argued that NATO’s 32-member composition inherently limits the partnership’s ability to act quickly like other small, purpose-driven strategic minilateral groupings, like the Trilateral Security Dialogue between Australia, Japan and the United States or the AUKUS partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States.55 Others cautioned that greater institutionalisation could constrain flexibility, exacerbate divergent threat perceptions, and potentially provoke adversarial responses or increase risks of horizontal escalation during a contingency. Several participants pointed out that other existing institutional structures, such as the China-Japan-South Korea Trilateral Cooperation Secretariat (TSC), do not guarantee meaningful strategic outcomes. For these reasons, many judged the informal nature of the NATO-IP4 arrangement as an appropriate format, particularly in its currently early stages, as it has lowered barriers to engagement and helped cultivate habits of dialogue among US allies and partners.

For other dialogue participants, the limits of informality are becoming clearer. The China-Russia-Iran-North Korea security axis has demonstrated the potential of transregional coordination, building a defence network that, as previously mentioned, has reinforced Russia’s war in Ukraine and accelerated North Korea’s military modernisation. Some participants noted in the absence of institutionalisation, transregional dialogue has tended to dominate at the expense of implementation, perpetuating consultation rather than cooperation. As a result, NATO’s convening authority emerged as both an enabler and a constraint. On the one hand, NATO remains the only established institution capable of gathering key Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific partners, providing unmatched credibility on shared, hard-security challenges that similarly large organisations, like the European Union, would struggle to muster.56 On the other hand, NATO’s centrality has skewed cooperation toward Europe-facing issues, rather than leveraging the partnership to generate strategic effects in the Indo-Pacific.

This dynamic is amplified by the trans-Atlantic-Pacific security partnership’s heavy reliance on US convening power. The Biden administration’s strategic framing of the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific was a decisive factor in driving momentum behind the NATO-IP4 partnership. Because cooperation between like-minded countries in the two regions is not heavily institutionalised, with no formalised structures to underpin more integrated security cooperation, the NATO-IP4 partnership has become especially malleable to US preferences on how its Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic allies and partners should, if at all, interact. Under the Biden administration, global strategic competition was framed as a systemic “battle between democracy and autocracy,” with the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theatres increasingly viewed as an integrated strategic space.57 As a result, the United States took the lead in facilitating a host of transregional security efforts, including, among others, the formation of the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) partnership in 2021, and the decision to invite key Indo-Pacific partners to NATO’s annual summits from the year after. The emergence of the IP4 as a grouping to directly engage Euro-Atlantic partners was conducive to, and in many ways a product of, Washington’s strategic thinking at that time. The second Trump administration, by contrast, has adopted a more differentiated approach, treating adversaries in each theatre as largely separate challenges. The Trump administration is pressing European allies to assume greater responsibility for their own regional security to free US defence resources for strategic competition with China, primarily in the Indo-Pacific, and is actively dissuading European powers from pursuing peacetime military operations and engagements in Asia.58

Establishing more deliberate coordination processes for IP4 dialogue could be a pragmatic first step, building coherence without prematurely institutionalising the grouping; fostering organic regional discussion without waiting for NATO or US convening power; and enabling the Indo-Pacific partners to identify areas of mutual interest where an ‘IP4 agenda’ might meaningfully be developed with NATO.

These shifts led several dialogue participants to advocate for more deliberate IP4 coordination mechanisms to ensure routine engagement among the four Indo-Pacific countries to mitigate abrupt changes in NATO or US policy. Participants emphasised that the goal of more deliberate IP4 security coordination would not be to supplant existing regional orders or create new geopolitical blocs, but instead to harness growing Indo-Pacific linkages to advance shared objectives in security and regional resilience, and ultimately complement existing alliance frameworks such as the ANZUS Treaty and the US–Japan and US–South Korea alliances. In this sense, establishing more deliberate coordination processes for IP4 dialogue could be a pragmatic first step, building coherence without prematurely institutionalising the grouping; fostering organic regional discussion without waiting for NATO or US convening power; and enabling the Indo-Pacific partners to identify areas of mutual interest where an ‘IP4 agenda’ might meaningfully be developed with NATO. This would not only help the IP4 become a more coherent and cohesive partner for NATO to engage with, but also help ensure the NATO-IP4 partnership delivers strategic effects in Asia — something that ultimately depends on the IP4 in articulating priorities and shaping where and how their collective cooperative efforts should be directed.

6. Dialogue participants warned about the risks of extending the NATO-IP4 partnership’s cooperative efforts on issues that fall outside of NATO’s typical mandate.

Many dialogue participants underscored that any effort to operationalise the NATO-IP4 partnership must begin with a clear understanding of NATO’s identity as a military alliance. While the Individually Tailored Partnership Programmes (ITPPs) span a wide array of non-traditional security domains, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the renewed urgency of sustaining a credible deterrence in both theatres have underscored that the most credible and strategically consequential basis for enhanced cooperation remains issues related to hard security. Several participants cautioned that expanding the agenda too broadly risks diluting political attention, institutional bandwidth and overall coherence of the transregional partnership.

This focus is equally important for strengthening coordination among Indo-Pacific partners themselves. The evolution of regional minilateralism shows that such mechanisms tend to succeed when anchored in a clearly defined remit. Participants pointed to the Quad’s expanding mandate and the strain this has placed on its effectiveness as a cautionary example, as well as the G7 and its attempt to “fix every problem,” to quote one dialogue participant.59 Accordingly, most agreed that the NATO-IP4 partnership should avoid overemphasising economic security or other peripheral issues that fall outside NATO’s core competencies, which could likely dilute strategic coherence or divert attention from the core deterrence and defence imperatives that have driven IP4 engagement to date.

7. Despite their shared security challenges, NATO and the IP4 lack a shared understanding of deterrence and approaches to crisis management.

Dialogue participants underscored that NATO and the IP4 lack a common conceptual framework for deterrence and crisis management, including in the nuclear domain, as the risk of sequential or simultaneous conflicts grows across Europe and the Indo-Pacific. The Russian threat, in particular, is no longer viewed as confined to Ukraine, while the risks of a conflict in the Taiwan Strait or on the Korean Peninsula have also intensified, with participants noting that crises could occur concurrently, whether coordinated by adversaries or unfolding independently, and could plausibly escalate to the nuclear level.

Given these dynamics, participants argued that NATO and the IP4 have stronger incentives to develop shared concepts of deterrence, particularly as many of the linkages fuelling the war in Ukraine shape the Indo-Pacific environment. A central task is articulating which deterrence model should articulate transregional coordination. One participant identified three broad pathways:

- Bifurcation: Treat the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic as distinct theatres governed by separate strategic logics and tailored deterrence strategies toward adversaries. While offering clarity, this approach risks IP4 and NATO members competing for US attention and defence resources, potentially producing uncoordinated postures with spillover effects across theatres.

- Cooperation: Treat threats as regionally anchored but intertwined. This model emphasises close coordination while maintaining distinct operational divisions, with Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic allies focusing primarily on their respective regions.

- Full integration: Conceptualise the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic as a single strategic theatre in which Eurasian adversaries function as a coherent bloc. This approach would require stronger connectivity between US alliance networks in both regions, deeper integration of command-and-control and defence planning, and potential organisational convergence between the United States Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) and the United States European Command (EUCOM).

While participants did not identify a single preferred pathway, there was broad inclination toward the cooperation model. Some dialogue participants also identified existing mechanisms that could provide practical foundations for enhancing shared deterrence concepts. The United Nations Command (UNC), founded in 1950 as a multinational military force to support South Korea during the Korean War and help enforce the Korean Armistice thereafter, was considered by several dialogue participants as a promising mechanism for enhancing shared deterrence concepts and even direct transregional security cooperation, should closer European defence participation in Indo-Pacific deterrence be called upon by the IP4 and NATO. Except for Japan, all IP4 countries are members of the UNC, and a broad set of European partners, including countries like Germany who were not originally involved in the Korean War, participate. Indeed, several European participants noted that the UNC’s standing mandate on the Korean Peninsula offers a politically and legally established entry point for European countries to potentially deepening their role in upholding Indo-Pacific deterrence and whose cooperation can help nurture and align deterrence concepts. By contrast, non-US Euro-Atlantic responses to other regional flashpoints such as Taiwan would be heavily shaped by US decision-making and lack of comparable multilateral legal or institutional structures to discipline a multinational approach. As such, the UNC may provide a viable venue for developing shared deterrence concepts, directly strengthening European engagement in the Indo-Pacific and potentially building the foundations for later developing shared crisis-escalation processes.

8. Complementarities within NATO and the IP4’s respective defence industrial bases remain underused, indicating opportunities to better align and leverage defence capabilities that could support deterrence and potential warfighting needs across both theatres.

Given the demands of the war in Ukraine and the rising risk of conflict in the Indo-Pacific, a majority of dialogue participants noted that defence industrial and technology cooperation offered a critical avenue for operationalising the NATO-IP4 partnership. Leveraging their respective strengths and technical know-how could accordingly bolster their defence resilience and capability development to meet both peacetime and anticipated wartime requirements.

To be sure, emerging transregional defence industrial cooperation efforts appear to be heading on a promising trajectory. South Korea has played a prominent role in this shift, having supplied hundreds of thousands of artillery shells to Ukraine and is now the second-largest arms exporter to European NATO members, with Poland accounting for 46% of South Korea’s European sales.60 NATO’s target of increasing members’ defence spending to 5% of GDP by 2035 further expands opportunities for cross-regional defence industrial collaboration, which South Korea is seeking to further. Indeed, at the June 2025 NATO Summit, South Korean National Security Advisor Wi Sung-lac met with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte to explore deeper defence-industrial cooperation opportunities, including Seoul’s potential participation in NATO joint development initiatives for next-generation energy systems and a proposed working-level consultative body.61 In October 2025, President Lee appointed Special Envoy Kang Hoon-sik to advance these efforts. Kang’s subsequent visits to multiple European capitals focused on prospective procurement projects, underlining Seoul’s growing enthusiasm for helping offset capability shortfalls across both regions.62

However, such collaboration remains highly contingent on conditions in the Indo-Pacific. Transregional defence-industrial cooperation, including arms transfers, often depends on the provider not facing an active conflict in its own theatre, where supplying equipment abroad could undermine in-theatre stockpile levels. In this sense, it will be critical for a diverse set of interregional and intraregional defence industrial partnerships to fill capability gaps and surge capacity during a conflict.

Australia’s extensive training ranges offer Japanese, South Korean, US and European partners opportunities to preposition munitions or test capabilities in relative safety and activate them rapidly in a contingency without early exposure to adversary strike threats.

This is also important among Indo-Pacific partners themselves, who lack the ability to scale defence industrial outputs as their counterparts in wartime Europe. Promising steps, however, include Japan’s provision of Mogami-class frigates for Australia’s future fleet, a development which will enhance the two countries’ interoperability and heralds Japan’s growing role as a complementary regional security enabler.63 US-Australia cooperation on expanding Australia’s Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance (GWEO) enterprise, alongside US support for Japanese fielding of Tomahawk cruise missiles and broader capabilities in integrated air and missile defence (IAMD) initiatives, illustrates the potential for more coordinated industrial planning.64 One dialogue participant also noted that as allied capabilities grow, they could be directed toward supporting Southeast Asian partners, who often view non-US suppliers as reliable, cost-effective and comparatively apolitical alternatives, particularly at a time when the US defence industrial base (DIB) is already struggling to meet surging domestic and allied demand.

Australia was also identified as a key provider of strategic depth for Indo-Pacific allies that lack geographic space for pre-positioning assets or conducting testing. Australia’s extensive training ranges offer Japanese, South Korean, US and European partners opportunities to preposition munitions or test capabilities in relative safety and activate them rapidly in a contingency without early exposure to adversary strike threats (see Figure 2). It could also be an important logistical staging ground for involved Euro-Atlantic players in a regional contingency.

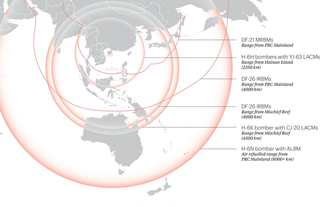

Figure 2. The increasing reach of China’s strike capabilities

DF-21 and DF-26 mainland ranges measured from open-source estimates of associated PLA Rocket Force bases. All ranges are approximate, given source limitations.

To maximise these efforts, NATO and the IP4 should conduct more rigorous assessments of the trans-Atlantic–Pacific defence industrial ecosystem to identify comparative strengths, critical gaps and viable channels for cooperation. The Partnership for Indo-Pacific Industrial Resilience (PIPIR) represents an existing yet untapped platform for doing so. Now comprising 15 Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic states, including all IP4 countries, PIPIR aims to strengthen collective industrial resilience through supply-chain cooperation, co-production and co-sustainment of defence assets.65 With limited time and resources, US allies and partners should divide labour based on comparative advantage, avoid duplication and better synchronise production timelines to help fill material shortfalls, including the US defence industrial base, to sustain shared deterrence requirements. Clearer demand signals for certain allied defence capabilities from Washington would further incentivise standardisation and interoperability, enabling allied industries to more effectively close remaining gaps.66

Dialogue participants also highlighted NATO’s Centres of Excellence — multinational institutions outside of NATO’s Command Structure that provide education, training, concept development and doctrine around specific issue areas like cyber defence and counterterrorism — as an additional mechanism for enhancing defence industrial and technological cooperation between the two theatres.67 Some Indo-Pacific partners already participate, such as Australia’s ongoing involvement in NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE).68 Expanding IP4 access to these institutions or replicating similar models in the Indo-Pacific would support the diffusion of expertise, best practices and advances in emerging technologies that will help underpin credible deterrence in the region.

Throughout all these efforts, NATO and the IP4 must remain clear-eyed about the necessity of working with the United States to realise these objectives since the US DIB remains indispensable for key technologies that underpin a credible deterrence. This is evident in US support for Australia’s and South Korea’s prospective pursuit of nuclear-powered submarines or, more immediately, Japan’s efforts to produce PAC-3 interceptors for Ukraine.69 In the case of the latter, production delays in Japan stemmed from restrictions on the local manufacture of US-origin missile seeker technology, coupled with production backlogs at facilities in the United States, highlighting the need to adjust export controls for capable, trusted US allies and partners, or at least engage in earlier planning to better align industrial requirements across the US alliance system.70

More broadly, NATO and the IP4 must make deliberate choices between federated and localised industrial models. Meeting near-term capability requirements will necessitate cooperation with technologically advanced partners, yet these efforts inevitably intersect with national priorities for sovereign industrial development, economic growth and market dynamics. A comprehensive mapping of capabilities and constraints across NATO and the IP4 defence industrial ecosystems is therefore essential to guide future decisions and sustain credible deterrence across both theatres.

9. NATO-IP4 security cooperation complements, rather than substitutes for, the United States’ indispensable security role in both theatres.

Dialogue participants stressed that the NATO-IP4 partnership is intended to reinforce, not replace, Washington’s central role in maintaining deterrence in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theatres. Efforts to frame the partnership as an alternative to US leadership would risk undermining alliance coherence at a time when strategic alignment is essential. This issue has grown more acute as Washington attempts to shift additional US defence resources toward the Indo-Pacific amid intensifying US-China competition. Indeed, some senior US officials, such as Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Elbridge Colby, have warned that ongoing commitments in Europe, and the war in Ukraine in particular, constrain Washington’s ability to deter China.71 This concern has been echoed in wargaming simulations that highlight the rapid depletion of key munitions in a Taiwan contingency in just eight days.72

However, despite non-US NATO allies’ recognition of the Indo-Pacific as the United States’ priority theatre and subsequent efforts to bolster sovereign defence capabilities, the United States remains irreplaceable for European security in the near-to-medium term.73 Non-US NATO members remain heavily reliant on US strategic enablers, including nuclear command and control, electronic warfare, cyber defence and a broader US defence industrial base that has supplied essential equipment for Ukraine and the NATO alliance. Many of these assets would take decades to replicate, particularly those underpinning Washington’s extended nuclear deterrence commitments.74 While recent allied initiatives such as the United Kingdom’s acquisition of US F-35-A strike fighters capable of carrying B-61 gravity bombs, or France’s intermittent interest in ‘Europeanising’ its nuclear deterrent, signal growing ambition among some European powers to assume greater leadership roles in nuclear deterrence, political appetite for supplanting the United States’ nuclear leadership role remains limited. These allied initiatives are unlikely to meaningfully substitute the deterrent effects provided by Washington’s substantially larger nuclear arsenal and posture in the coming decades.75

These dynamics highlight the potential for the NATO-IP4partnership to play a significant role in supporting US global strategy by bolstering cross-regional deterrence, managing the effects of shifts in US force posture and ensuring that rising defence investments produce mutually reinforcing capabilities.

Given finite US deterrence and warfighting assets, participants emphasised that uncoordinated shifts in US posture risk weakening deterrence in one theatre without producing compensatory gains in the other. Close coordination between NATO and the IP4 is therefore essential to anticipate capability gaps, align expectations and ensure that adjustments to US posture strengthen rather than fragment global deterrence. Through enhanced coordination, NATO and the IP4 can help prevent adversaries from exploiting perceived regional divisions and reinforce the credibility of allied strategy across theatres as the United States moves defence resources from Europe.

Participants further noted that rising allies’ defence expenditures across Europe and the Indo-Pacific will help strengthen collective deterrence, but only if new investments are channelled into complementary capabilities, in coordination with the United States. Canada and European states belonging to NATO have collectively raised defence spending from 1.43% of GDP in 2014 to 2.02% in 2024, amounting to more than US$485 billion. However, while all allies are expected to meet or exceed the 2% of GDP benchmark for defence spending in 2025, it still represents half of what the United States spends on defence.76 The IP4 are also increasing their defence budgets, though their combined spending stands at roughly US$160 billion: about one-eighth of US defence spending and one-quarter of China’s.77 As such, while higher defence outlays across NATO and the IP4 are essential for reinforcing deterrence in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific, their impact will depend on whether rising budgets are coordinated to address complementary capability gaps with the United States and each other, rather than duplicate existing capacities.

Taken together, these dynamics highlight the potential for the NATO-IP4 partnership to play a significant role in supporting US global strategy by bolstering cross-regional deterrence, managing the effects of shifts in US force posture and ensuring that rising defence investments produce mutually reinforcing capabilities. Realising this potential requires a clear-eyed recognition that the NATO-IP4 partnership does not seek to replicate US leadership. The aim of the transregional partnership is to help sustain credible deterrence in the Indo-Pacific and the Euro-Atlantic amid increasingly interconnected security challenges by complementing and strengthening existing security commitments with the United States.

Policy recommendations for NATO-IP4 governments

Over the past three years, the NATO-IP4 partnership has taken meaningful steps toward developing transregional security ties. Yet progress in translating a shared recognition that the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theatres are strategically “interconnected” into sustained, practical security cooperation has lagged behind these political statements of intent. To close this gap, NATO and the IP4 should consider the following actions:

- Recognise and prosecute NATO-IP4 security cooperation as a complement to, rather than replacement for, their respective ongoing security commitments with the United States.

NATO and the IP4 countries should recognise that, while their strategic contexts and security priorities vary, they share a sufficient level of convergence regarding the challenges facing them to justify more tangible security cooperation. Importantly, such efforts must be prosecuted with the understanding that the NATO-IP4 partnership is complementing their respective security partnerships with the United States, rather than an attempt to replace them. - Develop IP4 coordination mechanisms to reduce reliance on NATO and the United States as lead conveners, and help the IP4 become a more coherent and constructive partner for NATO to engage with.

Australia, South Korea, Japan and New Zealand should consider developing more deliberate coordination mechanisms amongst themselves to enhance intraregional dialogue. While not amounting to formal institutionalisation, such coordination could help comprehensively identify areas of convergence where intra-regional security cooperation can deliver meaningful security outcomes and inform a clearer IP4 agenda for engagements with NATO. These efforts should also proceed in parallel with each IP4 country’s Individual Tailored Partnership Programmes with NATO — a vital catalyst for sustaining transregional security cooperation — or bilaterally with other forums on transregional issues outside NATO’s core remit, such as economic security. - Enhance shared understandings of deterrence.

As strategic threats become increasingly interconnected, NATO and the IP4 should develop a common conceptual foundation for deterrence. Given that the NATO-IP4 partnership is still relatively nascent, the cooperative deterrence pathway offers advantages for NATO and the IP4 in coordinating around the reallocation of US defence resources toward the Indo-Pacific and clarifying partners’ respective objectives and roles during deterrence and potential conflict. Should NATO and the IP4 seek greater non-US Euro-Atlantic involvement in maintaining Indo-Pacific deterrence, the United Nations Command provides an existing institutional channel through which such cooperation can be organised and the alignment of deterrence concepts refined. - Expand IP4 participation in NATO’s Centres of Excellence and explore establishing Indo-Pacific equivalents.

The IP4 should broaden their engagement as observers in NATO’s Centres of Excellence to gain insights into best practices for addressing shared security challenges and help develop shared concepts of deterrence and adversarial behaviours. Drawing on their insights in Europe, IP4 and NATO countries could also consider establishing similar centres in the Indo-Pacific to further regional deterrence. - Map the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic defence-industrial ecosystems to support current strategic needs and sustain long-term deterrence in both theatres.

With limited time and resources, US allies and partners should divide labour based on comparative advantage, avoid duplication and better synchronise production timelines to help fill material shortfalls, including the US defence industrial base, to sustain shared deterrence requirements. Leveraging existing mechanisms, such as the Partnership for Indo-Pacific Industrial Resilience (PIPR), NATO and the IP4 should map their respective regional and national defence-industrial bases to identify complementary strengths, technical expertise and production shortfalls critical to maintaining deterrence and enabling warfighting across both regions. These assessments should also ensure that defence-industrial relationships, within the Indo-Pacific and between the IP4 and NATO, are sufficiently diverse and resilient so that a conflict in any one partner’s subregion or theatre does not become a bottleneck for broader industrial cooperation and supply. Reducing this vulnerability will also limit opportunities for adversaries to exploit supply chains through horizontal escalation.