Executive summary

Amidst a rapidly shifting strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific, strengthening defence industry ties between the United States and its regional allies has arguably never been more crucial. One promising feature of this effort is the US-Australia partnership on Australia’s Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance (GWEO) Enterprise. Endorsed by both the Biden and Trump administrations as a vital alliance initiative, this project could help boost munitions production and improve joint defence readiness. However, despite some notable progress — including the release of the Australian government’s GWEO Plan — the project still faces obstacles within both countries’ defence industries. As a result, its growth isn’t keeping pace with the region’s worsening security situation.

Amidst a rapidly shifting strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific, strengthening defence industry ties between the United States and its regional allies has arguably never been more crucial.

Policy recommendations

To help unlock GWEO’s full potential and overcome these barriers to ensure the United States and Australia maintain a credible deterrence posture in the Indo-Pacific, the following policy recommendations should be considered by the two countries:

For the United States:

- Recognise GWEO’s strategic value as a potentially important solution to US munitions shortfalls by extending and expanding the US industrial base — rather than replacing it.

- Integrate US efforts in GWEO with existing security frameworks such as the United States’ Partnership for Indo-Pacific Industrial Resilience initiative to strengthen deterrence, enhance supply chain resilience and align priorities across both national and allied efforts.

- Use GWEO as a pathway to broader reform, leveraging GWEO cooperation to reduce longstanding institutional and regulatory obstacles to deepen US-Australia defence industrial cooperation.

For Australia:

- Set a clear, long-term implementation timeline with ambitious but achievable milestones for the operationalisation of GWEO because failure to rethink timelines at an appropriate speed and scale may encourage the United States to seize remedies outside of Australian production.

- Secure bipartisan support for sustained investment, shielding the program from potential political turnover or any disruptive changes produced by electoral cycles.

- Map and assess munitions supply chains to identify key vulnerabilities and areas within the US alliance network where Australia could also help close capability gaps.

- Strengthen engagement between government and industry in order to foster mutual understanding of constraints, capacities, and operational realities to enhance coordination and delivery.

Introduction

Amid a deteriorating global and regional strategic environment, the United States has sought innovative ways to leverage the expanding defence industrial capabilities of its allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific. While the United States is no stranger to pursuing closer defence industrial integration with regional partners, such efforts have assumed greater urgency following a series of more recent, and often simultaneous, geopolitical shocks — from the COVID-19 pandemic to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, to renewed conflicts in the Middle East. These global developments have collectively underscored the need for the United States to work more closely with allies and partners as it strives to derisk critical supply chains and further US national strategic requirements, more broadly.

The onset of the second Trump administration and its ‘America First’ foreign policy agenda, however, has raised anxieties in allied capitals throughout the Indo-Pacific regarding the immediate and long-term impacts of continued defence integration and, indeed, reliance on the US defence industrial base. In the case of Australia — one of the United States’ closest global alliances and developing defence industrial partnerships — there is growing awareness of the challenges facing the US defence industrial base to meet its own defence requirements.1 Such challenges include the speed at which the US Department of Defense's acquisition system can deliver capabilities to its forces, which has been compounded by a longstanding aversion to risk within the acquisition process. Additionally, the complexity and weight of defence industrial regulations have subsequently extended the wait for technology release and processing time. And perhaps more fundamentally, issues on clearly defining ‘national interest’ have slowed the US Government’s approach to defence trade engagement with international partners.2

Australian awareness of these issues is especially pertinent in relation to the US submarine industrial base, where the scale and speed of its activity are closely monitored in Australia as a key indicator as to whether Washington will be able to deliver Virginia-class submarines to Canberra in the 2030s, as part of the AUKUS partnership.3 More broadly, though, are assessments indicating the challenge for the US defence industrial base to meet its own defence needs vis-à-vis the pacing strategic threat from China and other potential contingencies, let alone the needs of US allies and partners, that have accentuated such concerns.4

Recent US-Australia defence industrial efforts have positioned Australia as one of, if not the most consequential, US-allied defence industrial partnerships in the region.

Still, Australian officials and strategic documents continue to highlight the ongoing importance of the United States to Australia’s security fortunes and the broader Indo-Pacific.5 Moreover, recent US-Australia defence industrial efforts — including deepened maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) cooperation on aviation and subsurface combatants; enhanced logistical cooperation; and, not least, the AUKUS defence technology accelerator partnership to support Australia’s acquisition and sustainment of nuclear-powered, conventionally armed submarines — have positioned Australia as one of, if not the most consequential, US-allied defence industrial partnerships in the region.6 Indeed, senior US officials have described collective defence industrial production capacity and sustainment with Australia as a “blueprint” for Washington’s other global defence industrial partnerships.7 Both countries have proven willing to initiate significant reforms and investments to enhance their cooperation. One notable opportunity highlighted during Secretary of Defense Hegseth’s meeting with Australia’s Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Secretary, Richard Marles, in February 2025, was US-Australia defence industrial base cooperation on munitions.8

US-Australia cooperation on munitions can benefit from the strong foundation provided by Australia’s Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordinance (GWEO) Enterprise. Described by Australian defence experts as the “lynchpin of Australia’s national defence strategy,”9 the GWEO Enterprise aims to strengthen the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) munition and missile stockpiles and domestically manufacture guided weapons at the same time as supplementing its international partners’ supply chains.10 Although the GWEO Enterprise initially began as an Australian defence industrial effort responding to shifting regional strategic circumstances, it has since evolved into a distinct alliance initiative intended to meet joint requirements, complement US capacity and supply chains and support the United States’ broader forward deterrence posture.11

Yet formidable obstacles continue to hinder US-Australian efforts to achieve timely co-production and sustainment of munitions. A fundamental challenge derives from the fact that GWEO, if approached and treated as a standalone Australian defence industrial initiative, lacks a robust domestic demand to maintain sufficient momentum. Sustained Australian production will require substantial development underpinned by significantly greater access to the US market — currently a challenging proposition when US suppliers continue to hold commanding preference due to delivering military materials at a comparatively lower cost. Moreover, political momentum in Washington is leaning toward a more protectionist ‘Made-in-America’ doctrine, which risks disincentivising enhanced integration with allies, despite the evolving strategic environment gradually transforming Australia and other US partners into increasingly significant sources of prospective allied production lines. This friction is exacerbated by systemic constraints within the United States’ defence industrial and political economy. Cyclical budget negotiations, unresolved regulatory bottlenecks and an often-entrenched institutional aversion to long-term funding mechanisms have combined to create a relatively challenging investment climate. The reliance on short-term continuing resolutions has destabilised planning and procurement in the missile and munitions sector, rendering long-term defence industrial alliance initiatives like the GWEO Enterprise vulnerable to the vagaries of US domestic priorities and industrial preferences.

Given that Australia remains reliant on US technical expertise, intellectual property and supply chain access, the future of the GWEO Enterprise remains inextricably linked to political, strategic and economic developments in the United States.12 Sustaining momentum on advancing the GWEO Enterprise to help ensure that the wider regional strategic imperatives of the US-Australia alliance are fulfilled will require Washington to reconcile the aforementioned internal constraints with the external demands of pursuing a robust deterrence posture in the Indo-Pacific, including leveraging the developing defence industrial capabilities of regional partners like Australia.

Drawing on engagements with over forty Australian defence industry leaders, senior officials and relevant US interlocutors, along with an analysis of contract and trade data, this report describes the opportunities and barriers for US-Australia cooperation on GWEO. A starting point for this analysis is an overview of the munitions challenge in the United States, and the potential that cooperation can contribute to the furtherance of US strategic and defence industrial interests in the Indo-Pacific, its primary theatre of interest. It then identifies opportunities for such advancements, looking to the challenges of other allied defence industrial partnerships that can offer insights for the United States’ approach to cooperation with Australia on furthering the GWEO Enterprise. It concludes by offering recommendations to both Australian and US policymakers on how they can effectively manage the development of the GWEO Enterprise and enhance the chances that it will succeed. For the United States, ensuring that GWEO is linked to other ongoing efforts supporting forward deterrence will strengthen the likelihood of success. For Australia, a consistent focus on implementation — managing and funding the GWEO enterprise across administrations — will be necessary to sustain its forward movement.

The strategic and defence industrial case for enhanced cooperation on GWEO

Even before Ukraine’s demands for allied munitions after Russia’s 2022 invasion illuminated the limitations of Western stockpiles and the inability of industry to sufficiently surge, Australia had committed to expanding its munitions production through its Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance (GWEO) Enterprise.13 First announced in 2021, GWEO identifies a range of critical enablers aimed at strengthening the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) ability to acquire more sophisticated missile and munition capabilities.14 This includes targeted investment, significantly lifting capacity at factories to advance domestic production of more advanced forms of munitions and creating an enabling environment for deepened defence industrial cooperation with the United States.15

In October 2024, the Australian Government released its first formal GWEO Plan, which set out the “objectives, initiatives, resources and operating principles” of the enterprise.16 To be sure, the GWEO Plan is not without its critics. Disagreement within the Australian defence industrial community over the Australian government’s strategy extends to issues regarding the Plan’s stated timelines for capability acquisition and production; limited level of guidance regarding prospective roles and opportunities for Australia’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs); as well as the level of granularity on themes like workforce, supply chain, logistics, and testing and evaluation, all of which are necessary for industry planning purposes.17 Nevertheless, the GWEO Plan represents the culmination of years of development and is a necessary step toward the achievement of the enterprise’s stated goals and trajectory, including its emphasis that sustained and sophisticated cooperation with the United States will remain indispensable for the realisation of the GWEO Enterprise.

For the United States, defence industrial collaboration with allies has the potential to help mitigate many of the enduring challenges impacting its defence industrial base and add important surge capacity that can contribute to deterrence, or the necessary capabilities needed to prevail in a high-intensity conflict should deterrence fail.

For the United States, defence industrial collaboration with allies has the potential to help mitigate many of the enduring challenges impacting its defence industrial base and add important surge capacity that can contribute to deterrence, or the necessary capabilities needed to prevail in a high-intensity conflict should deterrence fail. Unlike the relatively benign global strategic environment during the immediate post-Cold War decades (notwithstanding the protracted US-led military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq), today’s rapidly shifting strategic circumstances, including support for allies and partners in their own conflicts, have given greater visibility and pressure on the aforementioned challenges currently inflicting the US defence industrial base.18 The struggle to compete with Chinese industry might have further illuminated the challenges facing the US industrial base and underlined the need for the United States to look to its international defence industrial partners to help develop US and allied defence capabilities vital to maintaining a credible regional deterrence posture.19

These challenges have led Washington to turn to its major treaty allies and defence industrial partners in the Indo-Pacific on a variety of efforts to enhance cooperation and contribute to forward deterrence. For example, the Partnership for Indo-Pacific Industrial Resilience20 (PIPIR) was initiated in 2024 and continues to offer an ongoing framework for working with US allies and partners. What some have described as Asia’s version of the Ukraine Defense Contract Group — which coordinated and channelled over 50 nations’ delivery of critical weapons systems to Ukraine — PIPIR could similarly fast-track the pooling of US allies and partners’ resources to deliver defence resources to the United States or vulnerable parts of the Indo-Pacific, even if a conflict breaks out.21 Moreover, compared to Europe, many of the United States’ Indo-Pacific partners already operate US military hardware and software, and conduct frequent joint exercises that ensure they are continuously familiar with US systems and aware of new variants.22 Additionally, the vision of the Regional Sustainment Framework (RSF) is to “(e)stablish a globally connected, resilient, defence ecosystem through collaborative regional sustainment strategies that leverage the strengths of our allies, partners, and the Defense Industrial Base, thus, ensuring the materiel readiness of the force in a contested logistics environment.”23 This will help collaboration between the United States, its regional partners and their respective defence industries by making them more closely linked, ensuring that US and allied warfighters have access to a dispersed network from which they can carry out Maintenance, Repair and Overhaul.

Fundamentally, the key drivers responsible for this shift in the United States and that are making allied defence industrial efforts, including the GWEO Enterprise, increasingly critical to US strategic and defence industrial interests include:

The munitions challenge

The outbreak — or threat of — major, and increasingly simultaneous, global conflicts has placed additional pressure on the United States to both maintain readiness levels and weapons stockpiles required for a credible US deterrence posture in the Indo-Pacific, while resourcing its allies and partners on the frontlines of secondary theatres. For example, the length of the Russia-Ukraine war and the number of munitions that have been expended have been an eye-opener for policymakers across the globe. The United States and other Western allies jumped to the support of Ukraine early in the conflict, sending existing systems and munitions to Ukraine with plans to refill stocks with the production of newer weapons.

In January 2025, the US State Department reported a total of “[US]$65.9 billion in military assistance since Russia launched its premeditated, unprovoked, and brutal full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022.”24 It included a list of capabilities across the warfighting domains, with the majority of such assistance being channelled towards the procurement of ammunition and missile weapon systems, as well as industrial base expansion.25 However, the extent of its support and the difficulties involved in surging manufacturing meant that replenishing stocks were not possible in the near term.26 This subsequently served as a wake-up call to the challenge of insufficient quantity in both inventory and manufacturing capability.27 The US Department of Defense and many outside analysts directly linked support to Ukraine with a generational opportunity to invest in the US defence industrial base, including munitions,28 creating a foundation to strengthen capability and capacity. This new foundation is necessary both as a fundamental part of deterrence and for success in military operations, should deterrence fail.

The length of the Ukraine war and the quantities of munitions that have been expended on sustaining Kiev’s war effort are just one of several strategic concerns informing US policymakers’ defence industrial decision-making. Renewed conflicts in the Middle East, including between Israel and Hamas in Gaza and Houthi attacks on international shipping in the Red Sea, have also underscored the particular importance of artillery shells, missiles and intercepting missile defence systems in modern conflict — and the vast rates at which they are consumed. In the case of the Israel-Hamas conflict, tens of thousands of munitions were expended by Israel in response to the October 7 attack during the first seven weeks of the conflict alone.29 The United States’ renewed commitments in the Middle East meant it had to draw on its own stockpiles of munitions reserved for other theatres. For example, to meet Israel’s initial requirement for 155mm ammunition, Washington was forced to use stockpiles reserved for the US European Command.30 This meant that tens of thousands of stockpiled shells originally intended to go to Ukraine were redirected to the Middle East ahead of Israel’s anticipated ground operations in Gaza; a particularly difficult move for Washington as Kiev’s reserves of 155mm artillery shells were vastly depleted and US NATO allies were strained to fill these gaps due to shortages in their own artillery shell stockpiles.31

Additionally, the United States expended hundreds of high-end strike and air defence missiles in defence of Israel and during air and maritime operations in the Red Sea to protect international shipping. Between November 2023 and July 2024, the US Navy estimates that the Dwight D. Eisenhower Strike Group launched over 800 missiles, including 155 standard missiles and 135 Tomahawk missiles, while its aircraft launched around 60 air-to-air missiles and 420 air-to-land missiles.32 Concerningly for the United States’ defence industrial base, the frequency in which these particular munitions were expended far exceeded past and foreseen procurement rates. A notable example of this issue includes the US Navy’s use of over 80 Tomahawk land attack missiles during the initial few days of its Red Sea Operations, which represented 145% of the Tomahawks procured in the previous financial year.33 These developments, and renewed conflict between Israel and Iran in June 2025, presage significant challenges to US strategic interests and defence readiness in the maritime domain of the Indo-Pacific, where such capabilities will prove critical to sustaining US deterrence and warfighting strengths in a primarily maritime domain. Indeed, the results of unclassified wargames by the Center for Strategic and International Studies involving a China-Taiwan scenario demonstrated the importance of missile strike capabilities, including large stockpiles of anti-ship cruise missiles and missile interceptor assets, should such a conflict break out.34

Ensuring that there are sufficient munitions stockpiled to deter or, if need be, sustain a long and difficult battle is hardly a new challenge. Acquisition experts have long observed the tendency in the United States to underinvest in munitions.35 This is a problem that has complex roots, with joint and service processes and congressional funding cycles contributing to the issue. The Munitions Requirement Process36 lays out the roles and responsibilities involved in munitions planning, with each military service working to procure enough munitions to successfully execute warfighting scenarios as laid out in the broader Pentagon strategy documents. Expectations about the length and extent of the conflict inform those plans. The unexpected transformation of Russia’s war on Ukraine into a prolonged ‘war of attrition,’ as well as the protracted conflicts in the Middle East, demonstrate the challenge of anticipating future requirements.37

Furthermore, no matter the requirement, munitions accounts have regularly been cut to fill funding shortfalls in other programs. The quantity of munitions and their relatively low unit cost make pulling funding to cover specific shortfall an easier maths problem than subtracting funds from other programs. Plans to compensate for such cuts in future fiscal years rarely come to fruition. Experts have warned of the concerning ramifications of this recurring underinvestment,38 but their cautions have not proven sufficient to create the case for changes to underlying investment dynamics in the US Congress. For example, before the outbreak of recent conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, then-Assistant Secretary of the US Air Force for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Dr Will Roper highlighted, in Air and Space Forces Magazine in 2019, the munitions challenge:39

Munitions…You’re buying a lot and you just buy fewer. And that may seem an easy choice on a tally sheet, but if you’re the acquisition person, and you take the buy lower, you just lost the economy of scale; you just made it harder for your vendor to forecast ahead and purchase materials and components in economic quantities…But one thing I wish we would do is just stabilize the munitions we buy each year and not make them bill payers, and allow our acquisition professionals to talk with their industry partners about five-year buys of components; five-year build plans.

Even before that, in 2016, it was reported that despite the US Air Force’s warnings that its stockpiles of precision-guided munitions were running perilously low amidst its air campaign against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, the US Air Force was still struggling to ramp up its stockpiles, meaning some of its allies, including some of its coalition partners fighting alongside the United States in the Middle East, had to be turned away from purchasing US precision-guided munitions.40 The United States’ then-Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics, Frank Kendall, noted that it is “probably fair to say that traditionally and historically, munitions have tended to be a bill payer.”41

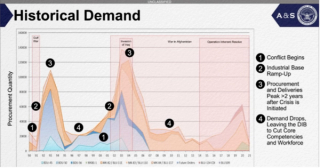

More recently, the Biden administration’s Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, Dr Bill LaPlante, offered a thirty-year look at historical demand for munitions (see Figure 1). History shows that it takes time to ramp up the US munitions industrial base after a conflict begins, with production reaching a peak after about two years. When the conflict is over, demand for munitions decreases again. Without contracts and funding to the industrial base, it shrinks and loses capabilities, including industrial competencies and workforce. The industrial base may shutter or sell facilities, shed tooling or reduce the number of workers with the tacit knowledge involved in complex manufacturing endeavours. Maintaining production at a lower level that meets near-term requirements keeps the industrial base active, but surging nevertheless remains a multi-year effort.

Figure 1. US Department of Defense demand for munitions, 1990-2021

Despite the immense US procurement budget, periods of ‘peacetime’ mean other capabilities take priority, and munitions investment declines. Though investment in the munitions industrial base is currently on the upswing, the US historic track record of inconsistent investment in munitions is a warning of the challenges ahead for Australia in maintaining sufficient investment over the longer term.

Inconsistent investment creates pressing concerns about warfighting requirements not being met in the event of a conflict. It also creates systemic challenges for the defence industrial base. Since contracts are most frequently awarded to the low-cost bidder, industry is incentivised to aim for production to be as lean as possible, without excess facilities, tooling, parts inventories and workers. Surges in production will require additional investments, both at the prime contractor level and throughout the supply chain. There may not be a sufficient business case for these investments without multi-year contracts.

Lower levels of demand may mean that competition is more difficult to sustain on component parts. It may be too expensive for primes to maintain dual sources of supply, or a lack of perceived demand may lead firms to exit the industry entirely. Though the United States has engaged in defence industrial policy in recent years, fixes to single sources and other constraints in the supply base will require additional attention and investments over the longer term if US munitions capabilities are to meet sufficient levels. Given the pressing shifts in the strategic landscape, the addition of second sources of supply can offer timely and critically needed defence materials that can fill these gaps and ensure that the United States and its allies are better equipped to uphold a credible deterrence posture or sufficiently equipped with the defence materials needed for a sustained and high-intensity conflict.

Challenges to US logistics in the Indo-Pacific

Not only has the rise of simultaneous conflicts in Europe and the Middle East raised global demands for US defence materials, but the shortfalls and diversion of US assets to other theatres have added further complications to the United States’ logistical and defence readiness in the Indo-Pacific. The long distances required for the US military to traverse between the US mainland and its Pacific territories or allied nations leave it increasingly vulnerable to China’s growing anti-access and area denial capabilities, including subsurface and long-range strike assets. The United States has attempted to mitigate these geographic challenges by expanding its military footprint across the region, and plans to quickly disperse its forces should a major conflict break out.42 However, efforts to develop a more dispersed network of military bases across the Indo-Pacific to enhance US deterrence and warfighting capabilities may yield limited benefits compared to the large, established bases in Japan and South Korea if these more remote outposts cannot be consistently sustained and resupplied.

Given the Indo-Pacific’s increasingly contested strategic dynamics, US logistical and resupply vessels supporting its forces in the Western Pacific would surely present an inviting target for a pre-emptive Chinese attack.43 It is in this context that US policymakers have sought to view its Indo-Pacific allies not only as geographic staging grounds or springboards for US forces, but also as partners whose growing defence industrial capabilities can complement US defence industrial requirements by acting as valuable secondary sources of supply.

Indeed, in April 2025, during his statement before the 119th Congress House Armed Services Committee, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs John Noah emphasised the need for “empowering” US regional allies and partners to share the burden of restoring and maintaining a credible deterrence posture. Citing Australia’s GWEO Enterprise as a key feature of these efforts, it is evident that senior figures within the US administration’s defence community are already recognising Australia’s potential contribution to US defence needs, including not only supporting its strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific, but providing important capabilities and tactical knowledge to support the United States’ homeland defence through major initiatives like US President Trump’s “Iron Dome” program.44 Indeed, during the US Defense Secretary’s remarks at the May 2025 Shangri-La dialogue, defence cooperation with Australia through GWEO specifically was identified as an important means of enhancing the readiness of their collective defence-industrial base.45

With challenge comes opportunity

As previously outlined, the crux of the challenge is that the inconsistency of demand and associated funding for munitions and missile stockpiles has resulted in a US industrial base inadequately postured to meet the demands of an effective forward deterrence posture and potential future warfighting needs. Indeed, recent US government and industry officials are working to address these challenges. For example, munitions were given considerable attention in the 2024 implementation plan for the National Defense Industrial Strategy (NDIS).46 This plan (which will likely be updated with Trump administration priorities) deliberately looks to US allies — including Australia’s GWEO Enterprise specifically — as part of the solution. During the first Trump administration, the US Department of Defense issued a report evaluating supply chain challenges.47 The second Trump administration’s initial National Security Advisor, Michael Waltz, was part of the bipartisan Defense Critical Supply Chain Task Force,48 which published a 2018 report highlighting challenges to developing resilient supply chains, a skilled workforce, more flexible acquisition processes, and other standards to ensure its domestic economic security, including its interactions with allies.49 Australia’s geographical proximity to potential conflict zones in the Indo-Pacific has helped cement Australia’s position as an important strategic partner to the United States and highlighted the potential of GWEO in strengthening US forward deterrence.

Australia’s geographical proximity to potential conflict zones in the Indo-Pacific has helped cement Australia’s position as an important strategic partner to the United States and highlighted the potential of GWEO in strengthening US forward deterrence.

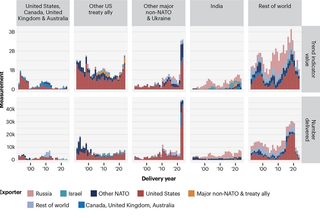

The first pillar of the alliance munitions opportunity is that there is sustained demand both in the United States and among US allies and partners for munitions and missiles that stands to level out valleys in any one country’s domestic demand. This can be seen in Figure 2, with the top row showing the number of missile or artillery systems imported and the bottom row showing the trend indicator value, an estimate of the production cost of those systems.50 The source of supply for complete systems from the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom, shown in the first column, is sometimes robust but highly variable. In contrast, the larger imports of other US treaty allies have been a steady source of imports even before the boom after Russia’s expanded invasion of Ukraine. Already the largest producer, the US NDIS notes a need for the United States “to better meet the global capability requirements of our allies and partners,” in part because US industry and acquisition projects first and foremost focus is on US operators and thus often neglect designing systems for exportability or scaling a factor to address uncertain global demand. This is an opportunity for a relatively smaller producer, such as Australia, to specialise and develop a comparative advantage within the munitions supply chain that addresses choke points within the broader allied defence industrial base and support US defence industrial needs. Given that Australia’s domestic demand is insufficient to sustain a sovereign industry like GWEO’s over time, these efforts will be especially critical for Australia to gain sustained access to partners’ markets, particularly the United States.

Figure 2. Missile, artillery and naval weapon deliveries by importer

The second pillar is integration with the US defence industrial base. Exports are possible without integration, but close cooperation is important to ensure that munitions produced in one country can be employed by an allied platform.51 In addition, when addressing large markets such as the United States, providing components or otherwise participating in the supply chain is often a more plausible avenue than the export of complete systems. This may also be a necessary foundation for larger-scale exports in the future, building familiarity between suppliers and officials and instilling confidence in the partner’s industrial base. Such integration faces many challenges, including the need to manage export control regulations along with a preference for domestic supply, even for countries that are exempt from “Buy America” rules because they have a reciprocal defence procurement memorandum of understanding52 with the United States. Nevertheless, supply chain integration is a useful step on the way to more ambitious cooperation, establishing the foundations for enduring partnerships built on demonstrated competency and growing trust.

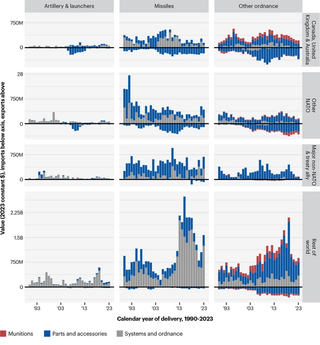

Trends in US arms imports and exports, as presented in Figure 3, provide both an opportunity and a caution for Australia. The good news is that the US government has a proven willingness to import parts and accessories.53

Figure 3. GWEO exports from and imports to the United States, by US relationship to recipient and ordnance category54

In the missile sphere, the United States imported US$4.7 billion in guided missile parts and accessories from Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada over the period with another US$4.4 billion coming from other NATO allies. Those three nations were also a leading source of propellent powders accounting for US$2.4 billion in imports, over three-quarters of all US imports in that category. Two other prominent categories of ordnance are “parts and accessories of military weapons” and “detonating caps, igniters, or other electric detonators.” Notably, over 40% of the US$5.6 billion in US imports in the dual-use detonators and igniter category came from countries that are not US treaty allies. This supply chain participation provides precedent for further expansion as part of GWEO to address the range of choke points facing the US munitions enterprise.

At the same time, the reason for the Australian Government to curb the extent of its enthusiasm is because there is presently very little import of complete systems to the United States. Missile parts and accessory imports to the United States almost exclusively come from NATO countries. However, while Australia has not been able to significantly participate in the past, the industrial base cooperation and regulatory reform catalysed by AUKUS, including a partial exemption to the International Trade in Arms Regulations (ITAR), has afforded Australia among the closest regulatory defence industrial integration with the United States of all US allies, alongside the United Kingdom and Canada. This may help overcome the hurdles to close supply chain integration with the United States.

Despite these promising developments, the experience of Japan’s response to the US demand signal for producing PAC-3 interceptors offers important insights to the United States and Australia about the broader challenges that US allies are currently facing when confronted with supply bottlenecks that only the United States produces. It was revealed in December 2023 that the Japanese Government would begin to export Patriot ground-based interceptor missiles produced domestically under license from US defence contractor Lockheed Martin to the United States.55 At that time, Japan already produced around 30 PAC-3 missiles each year, but the United States sought to dramatically increase this to fill US stockpiles. However, production was unable to take off since Japan required additional supplies of the missiles’ seekers (which guide them in the final stages of flight) that were only available from US suppliers. Boeing began expanding its seeker factory in the United States in 2023 to increase production by 30%, although it is reported that the additional lines won’t operate until 2027.56 Furthermore, even if enough seekers are available, dramatically expanding annual PAC-3 production in Japan beyond 60 would require Japan’s defence industrial base to build more capacity.57 The production snag in Japan shows the challenges Washington faces in plugging industrial help from its regional allies into its complex supply chains. Given Australia’s similarly smaller and emerging defence industrial sphere, beginning with export of components — as is the case of Australian rocket motors within the GWEO Enterprise — would be more sensible at this stage than the export of complete systems, the latter of which would likely also be dependent on strained US components.

Nevertheless, the increasing global demand for munitions and growing official recognition of the utility of having a source of supply closer to the fight may also contribute to the future demand signal and, in time, may evolve into a shift towards the Australian export of complete systems, along with contributing to the supply chain. The lessons on the importance of supply chain resilience revealed by the COVID-19 epidemic have continued to be salient and also may contribute to interest in working with allies located in the Indo-Pacific region.58

Recommendations for the United States and Australia in operationalising GWEO

GWEO is a strategic priority for Australia. The historic munitions challenge faced by the United States — and its many competing priorities include the capital-intensive and labour-intensive shipbuilding industrial base — also opens an opportunity for cooperation on munitions. Real global conflicts and insights from wargames and tabletop exercises all come to the same conclusion, which is that the allies do not have a strong enough munitions industrial base and have not stockpiled adequate munitions for a long war. The United States and Australia’s adversaries know this, and thus this represents a risk to deterrence and to the two nations’ safety and security.

Given Australian national priorities for GWEO, combined with the United States’ munitions challenge, there is a strong foundation for enhancing US-Australia cooperation on munitions.

Given Australian national priorities for GWEO, combined with the United States’ munitions challenge, there is a strong foundation for enhancing US-Australia cooperation on munitions. There are a range of options for the two nations to work together. The United States can procure components for munitions produced in Australia as part of a strategy to surge. The United States could purchase munitions built in Australian factories, where production could range from a more indigenous Australian supply chain to Australia performing final assembly from parts provided by a US contractor. The two nations could work together on setting a common requirement and engaging in joint development and production with integrated supply chains. Each of these strategies has opportunities and challenges, and each will benefit from being supported by some groundwork.

To sustain momentum on US-Australia cooperation on GWEO and ensure that production and important milestones are achieved that are commensurate with the evolving strategic environment, the two countries should consider the following options and recommendations:

For the United States

Understand the utility of GWEO as offering a potential solution to US capability challenges

The munitions challenges revealed by several global conflicts over the past three years remain unresolved, with testimony by US Navy leaders in May 2025 once again highlighting the strain on the industrial base.59 The United States can and should invest in expanding its munitions production, but that will come at a cost, and may pull resources including the constrained manufacturing workforce away from other priorities like shipbuilding. Ignoring what allies can bring to the table also reduces the opportunity to invest in the network of allies and partners that is key to the United States’ deterrence posture — and to its warfighting success. Australia’s location closer to a potential conflict offers a solution to the challenge of contested logistics. Munitions cooperation with Australia will sustain that nation’s industrial base in the face of its smaller demand and will support opportunities for allied surge production.

Recommendation 1: Recognise the opportunity that cooperation on GWEO represents

- In the United States, munitions investments have been variable over time. Developing and maintaining surge capacity in any industry is expensive, and supporting the development of Australia’s munitions enterprise would be beneficial to enhance surge, while reserving funds for other administration priorities like shipbuilding.

- For the Trump administration, working with Australia would create a sustained approach to deterrence across administrations, and limit the ability of adversaries to potentially pull the United States apart. The Trump administration’s industrial base warnings in its 2018 supply chain report and focus on China, are themes that have reappeared in the second administration’s initial guidance.60 Secretary Hegseth’s identification of the GWEO Enterprise during his remarks at the Shangri-La Dialogue in May 2025 is a welcome development, underlining the administration’s recognition of continued US support.61

- Ultimately, defence industrial cooperation with allies and partners extends and expands the US industrial base rather than replaces it. As Australian government officials encapsulated it, each country’s industrial base isn’t going to be able to achieve everything, so cooperation is critical.62 Cooperative production agreements will extend and expand allied capability — combined industrial potential is needed to meet the common security challenges facing Australia and the United States.

Strengthen the link between munitions cooperation and other partnership efforts

US government leaders have efforts underway to address the industrial base challenges that the United States would face in any conflict in the Indo-Pacific, and these have persisted across the January 2025 change in administration from Biden to Trump. Deliberately connecting work with Australia on munitions cooperation to these broader frameworks will enhance visibility into Australia’s potential role in addressing the munitions challenge. PIPIR63 was initiated in 2024 and continues to offer an ongoing framework for work with allies and partners.

Recommendation 2: Link existing Pentagon efforts with GWEO

- Linking any existing Pentagon efforts on GWEO with the PIPIR initiative will highlight American participation in GWEO as a contribution to the supply chain resilience goals of that initiative. The RSF offered initial projects to a variety of partner nations. One possible approach to making capability available that would also support GWEO could be using the enterprise to repair American weapons in the region, rather than sending them back to the United States homeland.

Include a supply chain focus in cooperation efforts

Constraints in the industrial base do not begin and end with the final assembly of materiel. Munitions are complex systems with a range of inputs, and increasing production requires investments across the supply chain. US efforts at enhancing “supply chain illumination” — that is, providing the US Department of Defense with greater transparency over its supply chain by identifying multi-tier supplier networks, vetting suppliers against Defense’s specific criteria and addressing potential risks to supply64 — can help identify constraints in the broader industrial base. Working with allies on what they can provide to the overall supply chain can help address supply challenges and support the opportunities for surge. Australia’s focus on GWEO offers a capable nation for the United States to partner with.

Recommendation 3: Partner with Australia to enhance supply chain resilience

- Australia can supply parts for new production of weapons and for repair. Including Australian industry inputs into the supply chain will enhance resilience through the development of a second source of supply.

Focus on overcoming barriers for defence industrial cooperation

The different pathways of cooperation all require work to overcome barriers to defence industrial cooperation. Other studies on bilateral defence industrial cooperation between the two nations65 identified a series of challenges across domains including budgetary, bureaucratic, cultural, political, regulatory, strategic, technical and economic. The analysis suggests that while it is worthwhile to address each individual challenge (for example, the regulatory complexities of the International Traffic in Arms Regulation regime or the economic challenge of making sure that the right incentives are in place to induce industry to participate), the two governments should focus on ensuring the ecosystem, as a whole is, designed to support cooperation.

Recommendation 4: Understand the ecosystem nature of barriers to cooperation and work to address them all

- Although the Australian Government’s 2024 GWEO Plan offered a roadmap for the Enterprise’s development, senior defence industry representatives note that details on key ecosystem enablers such as workforce, supply chain, logistics, and testing and evaluation are absent from the plan or lacking in the granularity required for industry planning purposes. Defence industry representatives noted that irrespective of ‘big’ announcements on capability selection and acquisition, a lack of sustained and targeted investment in adjacent ecosystem-level levers will prevent sovereign production from materialising at the speed of relevance.

For Australia

The unmet demand in munitions offers a timely opportunity for Australia’s investment in GWEO and its focus on defence industrial strategy as laid out in Australia’s Defence Industry Development Strategy (DIDS).66 If the United States were to cooperate with Australia on GWEO, Australia will need to invest in its own enterprise. The challenge for the Australian Government will be to maintain a sustained focus on these goals over time. Roundtables and discussions held in Canberra with both industry and government officials with the authors highlighted a number of specific challenges. Specific recommendations for the Australian government to support the goals of the GWEO enterprise include:

Focus on implementation

The United States’ Congressional Research Service (CRS) notes that “industrial policy commonly refers to a comprehensive, deliberate, and more or less consistent set of government policies designed to change or maintain a particular pattern of production and trade within an economy.”67 The Australian Government has recognised the importance of industrial policy, with the “Future Made in Australia” effort.68 GWEO does meet outcomes suggested by the CRS definition — that is, to develop a particular pattern of production and trade. To achieve success, the government should invest in comprehensive, deliberate and consistent policies to get there.

Recommendation 1: Establish a long-term timeline for operationalising the GWEO Enterprise with more ambitious, but achievable, milestones

- Deliberately understand and manage GWEO as industrial policy with investments over time. Although the Australian Government’s latest GWEO Plan offered a roadmap for the Enterprise’s development, defence industry concerns underline the risks associated with planned action steps and a misalignment between production plans and the growing demands imposed by the shifting strategic environment. Failure to rethink timelines at appropriate speed and scale may encourage the United States to seize remedies outside of Australian production. The Australian Government’s next GWEO strategy document should play closer attention to addressing these risks.

Recommendation 2: Sustain bipartisan support for long-term funding

- Securing consistent financial backing across electoral cycles and changes in leadership will provide stability and confidence within Australia’s defence industry while reinforcing its credibility as a dependable partner and a viable secondary supply source for allies like the United States. While this has in part been achieved by the re-election of the Albanese government with a major increase in its majority ongoing bipartisan support is critical for a long-term national endeavour such as the GWEO Enterprise.

Address the challenges of scaling GWEO

Australia’s relative domestic demand means that it would be difficult to sustain its GWEO enterprise by strictly delivering upon national requirements, given the relatively limited domestic demand represented by the Australian Department of Defence. Australian industry representatives highlighted past programs where they stood up production lines, only to have to close them later when the orders were completed.69 Consistent exports to the United States would keep the factories open, although Australian industry representatives expressed concerns about hesitation on the part of the US to place orders with Australian industry.70 Australian government officials concurred about the challenge and also agreed that exports were a solution to the challenges of continuity of demand and economies of scale — one that they hoped also aligned with US government interests. Supporting an export market will require leadership from the Australian government, something that is already a focus of Australian Government activity.

Australian government leaders highlighted that partners tend to prioritise their own national defence industrial bases, with the benefits from cooperation being a second order interest. But as one official noted on making case for partnering: “Each country’s industrial base isn’t going to be able to achieve everything, so cooperation will still be there.”71 The United States has its own munitions challenge which could be mitigated by cooperation with Australia.

Recommendation 3: Strengthen US confidence in Australia’s strategic and industrial role

- Canberra should maintain and expand its diplomatic engagement with Washington, working closely with the 119th Congress to assess the effectiveness of reforms introduced in the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA)72 and explore further regulatory adjustments, such as revising the excluded technology list. These efforts would help mitigate biases favouring US-based supply sources and support broader integration into the Global Supply Chain initiative.

Address regulatory regimes

Australian industry bodies and officials must be in lockstep in prosecuting both the strategic and business case for collaboration and overcoming impediments to maturing the defence industrial relationship. These include the ongoing challenges created by export control regulations, including the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) regime. Australian defence industry representatives appreciated the importance of recent updates to ITAR and those linked to the AUKUS agreement, but were concerned by the range of capabilities that remain on the technology exclusion list and the impact that would have on bilateral munitions trade.

Australian industry bodies and officials must be in lockstep in prosecuting both the strategic and business case for collaboration and overcoming impediments to maturing the defence industrial relationship.

Recommendation 4: Focus on regulatory reform

- The Trump administration has already given firm indications of a desire for increased foreign military sales and the potential of reforms to munitions production and regulatory reform. This opens opportunities for Australia to recommend reforms to areas such as the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), ITAR, Militarily Critical Technologies List and so forth.

Strengthen supply chain visibility

Industry and government raised that the Australian Department of Defence sometimes lacks visibility across the supply chain and, therefore, has a limited view of shortfalls that may frustrate GWEO production efforts. They remarked that an absence of supply chain illumination makes it more difficult for the Australian Department of Defence to either collaborate with or direct Australian industry to strategically plug gaps in the supply chain. Supply chain illumination is a consistent challenge in many contexts, and the DIDS does support the development of industry intelligence.

Recommendation 5: Map the munitions supply chains and understand their constraints so that Australia can better develop its own GWEO enterprise and identify places to invest that could help the United States fill its capability gaps

- Support efforts to overcome the reported preferences in the United States for US-based sources of supply of components, through the Global Supply Chain effort and other approaches as appropriate

- Assess and aim to address the shortfalls and supply challenges within the larger US alliance ecosystem, such as rocket motors. Supply chain illumination is always a challenge, so working with the US side to identify the areas of greatest need would help.

Enhance governmental understanding of industry

Industry and government officials highlighted that a number of government officials often lacked knowledge of industry incentives and operations, including supply chain management and challenges. The disconnects between Australian government agencies and the defence industry regarding roles, priorities, and their respective challenges should be better understood and addressed. Government bureaucracies should deepen their understanding of industry-specific issues to foster enduring partnerships with industry and ensure that discussions with industry stakeholders focus on the right questions early in the process, which can be aided by growing Australian efforts to enhance business intelligence. This alignment will help better translate strategic objectives into actionable outcomes. Indeed, one defence industry leader acknowledged that “Australia currently lacks defence industrial people” in its government departments.73 While addressing this is not specific to GWEO or unique to the Australian context, an “education with industry” program for government officials may address the gaps and help the Australian government more effectively manage and incentivise industry.

Recommendation 6: Develop government-industry relationships

- Better educate government leaders in how industry works, so they can partner more effectively and build enduring partnerships to support the GWEO Enterprise’s ambitions.

Enhance industry understanding of government

Overall, industry was hopeful about the opportunities represented by participating in the GWEO Enterprise but were concerned about whether the Australian Government would be able to develop and sustain an execution plan to ensure funding and support over the long term. However, it should be noted that the new Defence Industrial Development Strategy (DIDS) includes several actions that relate to the observations that industry raised.74 Nevertheless, the author's interviews with Australian defence industry representatives found that the DIDS was rarely mentioned. This could suggest that the Australian defence industry is either less familiar with the strategy (and thus the Australian Government should explore new strategies that enhance similar future strategies’ dissemination) or that they do not yet see the government’s plans as sufficient to address the gaps and challenges they see. In either case, it would be useful for the Australian Government to communicate plans to industry more effectively, as laid out in the DIDS plan.

Additionally, industry reactions to the Albanese government’s October 2024 GWEO Plan underscored that while the government has certainly demonstrated its commitment to realising GWEO as a defence initiative central to Australia’s security, senior industry stakeholders believe that such rhetoric — and broader strategic document’s emphasis that Australia is facing the most challenging strategic environment since the Second World War75 — does not match the speed and scale of progress currently underway.76 They emphasise the need for the GWEO Enterprise to accelerate its efforts and address key enablers such as workforce development, certification, supply chains, logistics, and testing and evaluation, which will all be essential to achieving its objectives over the long-term.77

Recommendation 7: Develop industry-government relationships

- Work to set expectations with industry so they have a deeper understanding of the challenges ahead and ensure government has an understanding of industrial hurdles and when to seize arising opportunities at different junctures of the GWEO enterprise’s development. While immersing government officials in the private sector for a period of time or directly hired into public service from industry may create conflicts of interest, a better understanding of defence industry challenges and mechanics is fundamental for establishing strong public-private relationships to deliver the GWEO enterprise.

The production of this report was supported by Thales, Raytheon and Lockheed Martin as part of a research partnership.