Foreword

The United States Studies Centre is pleased to publish this seminal assessment of the changing economic security landscape in both the United States and the world, as well as the implications for Australia’s own statecraft.

The Centre has made economic security a centrepiece of our work as this global transition has evolved, leveraging expertise and insights from the United States, Japan, South Korea and other like-minded allies and partners, and convening senior government officials and private sector experts. Since joining the Centre in 2023, Dr John Kunkel has been a leader in this effort, working with the Economic Security team to deliver major conferences and roundtables on the rules of the new order, the implications of artificial intelligence, the energy transition, and critical mineral supply chains. This report draws from those exchanges in addition to extensive consultations in Canberra, Tokyo and Washington. And, of course, it benefits from John’s own doctoral training in economics and extensive experience working in both industry and government.

The report provides a clear account of how the consensus behind the international rules-based economic order unravelled and highlights the best practices in economic security being pioneered by Japan and other governments. Tempered by the recognition that we do not yet know what is fully gone, what can be rebuilt, and where we must innovate — the report nevertheless offers an international context for assessing Australia’s own efforts at economic security with the Future Made in Australia industrial policy. The conclusions are a reminder that Australia cannot design these policies in a vacuum and would do well to align closely with Japan and other like-minded nations while keeping an eye on the opportunities to play a role in America’s unfolding debates on trade, secure supply chains and technology policy — which will ultimately be most consequential in defining the new tools and rules as geopolitical competition with China remains intense.

We hope that readers in all sectors benefit from the historical, economic and policy analysis in these pages. And we encourage you to continue following the economic security work at the Centre going forward.

This report was made possible through a generous grant provided by the Centre’s previous Chairman of the Board and current distinguished fellow, Mark Baillie. The Centre is grateful to Mark for his leadership and support for over a decade.

Dr Michael J. Green

Chief Executive Officer

Executive summary

The global economic order is in flux. Globalisation is not over, but it is fragmenting. Trade restrictions and industrial subsidies have surged, and the use of other tools of economic statecraft — including sanctions, export controls and investment restrictions — has never been higher. Governments are turning increasingly towards defensive measures and ‘economic security’ strategies to defend national interests.

At the heart of this Great Unravelling is the demise of roughly eight decades of US economic grand strategy. The nation that led the creation of a liberal economic order following the Second World War, with added ambition at the end of the Cold War, now views that order as a weaponised instrument of unfairness that has weakened the United States. The once-ascendant ‘Washington Consensus’ — a set of policy principles geared to fostering economic interdependence between nations through greater reliance on open trade, capital and technology flows — is in eclipse in its eponymous home.

The once-ascendant ‘Washington Consensus’ — a set of policy principles geared to fostering economic interdependence between nations through greater reliance on open trade, capital and technology flows — is in eclipse in its eponymous home.

A combination of external and internal forces shattered the political foundations of the old Washington Consensus in the early 21st Century, leading to a crisis in the American trade policy regime. In understanding this crisis, this paper directs attention to the intersection of a prolonged period of sluggish growth in living standards at the bottom and middle of the American income distribution and the concentrated hollowing out of US manufacturing jobs from the so-called ‘China shock’. The political pressures unleashed gained added potency in the wake of the global financial crisis (GFC) and the subsequent Great Recession, opening the door to Donald Trump’s assault on trade and globalisation at the 2016 US presidential election.

The challenge presented by a more powerful and ambitious China provided the coup de grâce to the old Washington Consensus in the second decade of the 21st Century. China’s rise to manufacturing dominance in key sectors and technologies and its more assertive grand strategy under Xi Jinping have prompted a profound rethink in Washington about the economic underpinnings of US power. A solid bipartisan consensus now sees globalisation and China’s unwillingness to ‘play by the rules’ of the postwar order as hollowing out US manufacturing, in the process destroying the livelihoods of millions of workers.

President Trump’s America First trade agenda broke with the established order. The first Trump administration embraced tariffs to a degree not seen since the 1930s. In 2018, President Trump launched a series of trade actions that ratcheted up tariffs on China and on select products from other trading partners, including US allies. Under the Trump administration, strategic competition with China moved to the centre of US national security policy, albeit conditioned by the president’s idiosyncratic approach to international diplomacy.

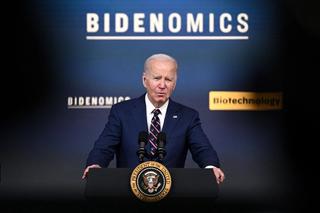

Following the 2020 election, Joe Biden’s expansive view of government cemented a new paradigm of state power grounded in rejection of liberal economic orthodoxies, acute aversion to market-opening trade agreements and strategic rivalry with China. The Biden administration left most Trump tariffs in place and deployed further targeted tariffs on China. ‘Bidenomics’ also saw the revival of a US tradition of active industrial policy via three major pieces of legislation — the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act. A comprehensive regime of export controls designed to deny the United States’ primary strategic rival access to advanced technologies would form a signature element of the Biden administration’s China policy.

President Trump’s return to the White House and his 2025 trade war have sanctified the overthrow of the old economic order. Politicians on both the left and the right in Washington, as well as thinkers and activists across the US political spectrum, have repudiated the ‘neoliberal’ project of the past half century in favour of a more state-directed, nationalist and security-oriented approach to economic policy. A shifting and indeterminate combination of tariffs, industrial interventions, investment screening, export controls and sanctions now forms the economic toolkit of the new Washington Consensus.

The Great Unravelling is not simply Made in America. China’s rapid emergence as the world’s major manufacturing power and its mercantilist model of state capitalism fractured old power structures and core assumptions of the post-Cold War economic order. The China challenge, in all its dimensions, is a key reason why governments across the Global West and the Global South have reshaped economic policies in recent years through a lens of resilience and security.

The rise of the “economic security state” has seen governments deploy new strategies and tools aimed at protecting domestic industries and technologies, boosting growth and competitiveness, accelerating the green energy transition, and defending national sovereignty and security in the face of heightened geopolitical threats. The quest for greater security and resilience through increased government intervention and guidance of the economy will remain deeply contested policy terrain, including in the United States. There will be no return to the status quo ante, but nor is there firm ground on which to plant a new economic paradigm as financial market volatility, court challenges and declining popularity of President Trump’s economic agenda after less than a year in office all attest.

The quest for greater security and resilience through increased government intervention and guidance of the economy will remain deeply contested policy terrain, including in the United States.

This new era of economic statecraft presents profound policy challenges for Australia, a mid-sized open economy with the United States as its cornerstone security ally and China as its largest trading partner. The Australian Government’s main policy initiative aimed at navigating geopolitical upheaval and economic fragmentation is the Future Made in Australia (FMIA) agenda. The two main goals of FMIA are to help Australia succeed in the global net zero economy and to reinforce national security and economic resilience amid increasing geopolitical disorder and economic uncertainty.

This paper argues that FMIA suffers from political overreach and an unbalanced emphasis on the green transition relative to core strategic challenges and interests. It recommends that future investments be guided by risk-based assessments of major economic security vulnerabilities and opportunities for Australian strategic advantage.

The Australian Government should enshrine ‘strategic indispensability’ as a core guiding principle for FMIA investments, taking a cue from Japan’s economic security strategy. Based on both strategic and economic grounds, Australia has a unique opportunity to make critical minerals and rare earths the fulcrum of a new era of successful industry policy that aligns national security and economic security interests.

A refashioned Future Made in Australia strategy will require Canberra to build enhanced analytical capability and policy muscle. To this end, the Australian Government should establish a new National Economic Security Agency (NESA) within Treasury to assess major economic security risks and to advise government on measures to mitigate such risks and to build critical national capability.

Building on existing agreements, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, in coordination with NESA, should be charged with negotiating a new network of Economic Security Partnerships (ESPs). These partnerships would aim to strengthen key strategic and economic relationships, coordinate economic resilience initiatives among like-minded countries and unlock opportunities for Australian industry as global value chains are reset in coming years.

An Australia-Japan Economic Security Partnership would be the natural starting point of this initiative, given the close alignment of strategic and economic interests. The Australian Government should, at the right time, look to upgrade the Strategic Commercial Dialogue with the United States to put economic security discussions on a parallel footing with those on national defence and foreign policy.

Policy recommendations in brief

1. Reshape the Future Made in Australia agenda to ensure a greater focus on national security and economic security challenges, risks and opportunities.

- Make ‘strategic indispensability’ a guiding principle of industry policy under the FMIA National Interest Framework.

- Gear the Framework to integrated assessments of strategic risk and economic opportunity when recommending sectoral or firm-level investments.

- Use the 2026 review of the Critical Minerals Strategy to better define policy priorities in this sector.

2. Establish a National Economic Security Agency within the Australian Treasury with a mandate to assess major economic security risks and to advise government on measures to mitigate such risks and to build critical national capability.

- Have the secretaries of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Treasury, Foreign Affairs and Trade, and Defence set NESA’s annual work program, as approved by the National Security Committee of Cabinet.

- In advance of any formal economic security strategy, have the Treasurer make an annual statement to the Australian Parliament on economic security interests, risks, policy objectives and guiding principles.

3. Charge the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade with negotiating a new generation of Economic Security Partnerships.

- Approach Japan as partner of choice for the first Economic Security Partnership, building on Australia’s free trade agreement with Japan and the existing bilateral economic security dialogue.

- Explore the scope for modernised energy security and food security chapters as part of these partnerships.

- Look to upgrade the Strategic Commercial Dialogue with the United States into a regular ministerial meeting with Cabinet-level representation from the respective Treasury departments.

- Work with like-minded partners to develop a doctrine of economic statecraft that aspires to limit the overreach of restrictive and punitive measures.

1. Introduction

The global economic order is in flux. An era of deepening economic integration has given way to one marked by geopolitical upheaval, intensified great-power competition, resurgent economic nationalism and a diminished role for multilateral institutions, rules and norms. Globalisation is not over, but it is fragmenting.

The Trump trade wars that have lifted US tariffs to their highest levels in a century are one manifestation of a more fractured, contested and volatile global environment. China’s outsized manufacturing trade surplus and state subsidies are another, as the world’s second-largest economy looks to cement market dominance and self-sufficiency in key sectors and technologies. Other countries and regional groupings are turning increasingly towards defensive measures and active ‘economic security’ strategies to protect domestic industries and to secure geopolitical and economic interests. Bouts of economic warfare now characterise a new era of weaponised interdependence in the global economy.1

This transformed global economic environment is roughly a generation in the making. The period since the 2007-08 global financial crisis (GFC) has seen a levelling-off of international flows of goods and capital and a surge in trade restrictions in the past few years (Figure 1.1).2 Resort to active industrial policies, with targeted support for domestic sectors and firms, has grown markedly.3 The use of other tools of economic statecraft — including sanctions, export controls and investment restrictions — has never been higher.4

Figure 1.1. Number of restrictions imposed annually worldwide (2010–2023)

The sources of this Great Unravelling are deep-seated, complex and over-determined. The list of variables with some claim to explanatory power includes large and persistent macroeconomic imbalances, financial shocks, sluggish economic growth, disruptive technological change, rapid migration flows, discontent with the unequal benefits of globalisation, US foreign policy adventurism, China’s assertive projection of geopolitical, military and economic power, Russia’s external aggression, the threat of climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic.

This paper focuses on one Janus-faced vector of cause and effect — the retreat of the United States from leadership of the global economic order. The nation that led the creation of the post-1945 rules-based, liberal international order among Western democracies, with added ambition at the end of the Cold War, now acts as a grievance-laden disruptor of established rules and norms. The once-ascendant ‘Washington Consensus’ — a set of policy principles geared to fostering economic interdependence between nations with greater reliance on open trade, capital and technology flows — is in eclipse in its eponymous home (Box 1.1).5

Box 1.1. The (old) Washington Consensus: What is it and where did it come from?

The term Washington Consensus serves as shorthand for what supporters and critics alike regard as pillars of economic orthodoxy aligned with a liberal economic order. The association with Washington, DC, reflects the intellectual hegemony and institutional power (at least for a period) exercised by the home of the US Department of the Treasury, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

The origins and aspirations of the original Washington Consensus are more complex and nuanced than often portrayed. Authorship belongs to the late John Williamson, a former senior fellow at the Institute for International Economics (now the Peterson Institute for International Economics). The phrase, a pithy attempt to capture lessons for growth and development, was used initially in a 1989 background paper for a conference focused on Latin American economic performance.6 Williamson sought to distil these lessons into a set of policy principles reproduced and simplified below:

- Reduce national budget deficits

- Redirect spending from politically popular areas toward neglected fields with high economic returns and the potential to improve income distribution, such as education and health

- Reform the tax system by broadening the tax base and cutting marginal tax rates

- Liberalise the financial sector with the goal of market-determined interest rates

- Adopt a competitive single exchange rate

- Reduce trade restrictions

- Abolish barriers to foreign direct investment

- Privatise state-owned enterprises

- Abolish policies that restrict competition

- Provide secure property rights.

Williamson never proposed the Washington Consensus as a one-size-fits-all set of policy prescriptions, much less a solvent for geopolitical rivalries or the distributional consequences of market-based resource allocation in an integrated global economy.

1.1. From Trump’s tariffs to Bidenomics — and back again

With blind spots and exceptions, the United States played the leading role after the Second World War in fostering reciprocal liberalisation of trade along with a set of rules and norms designed to govern international trade relations — through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) initially, and later via the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO). For roughly eight decades, including through the long twilight struggle of the Cold War, a core objective of US foreign economic policy was to negotiate market-opening trade commitments in support of US commercial and geopolitical interests.

With the embrace of America First mercantilism, the first presidency of Donald J. Trump broke with this broadly bipartisan approach to international trade relations. As a New York real estate magnate outside of elite policy circles in the 1980s, Donald Trump railed against free trade, arguing the United States was being “ripped off” by other nations.7 The United States’ trade deficits were deemed evidence of unfair foreign practices, despite protestations of mainstream economists to the contrary. Economic relations between nations were cast as a zero-sum game of winners and losers. To citizen Trump, the United States was the biggest loser from past trade agreements. These beliefs would become foundational to Trump’s future political ambitions.8

As the party’s nominee and then president, Trump oversaw the Republican Party’s abandonment of free trade as part of its political platform and governing agenda. On his first full day in office in 2017, President Trump withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiated under President Obama. His administration set about renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and in 2018 Trump launched a series of trade actions that ratcheted up tariffs on China and on select products from other trading partners, including US allies and partners.9 “Trade wars are good, and easy to win,” President Trump declared on social media in March 2018.10

Joseph Biden came to office following the 2020 election, disavowing the transactional approach of his predecessor and promising a renewed focus on US alliances. Despite some course correction, however, free trade would remain politically friendless at the highest levels of the US Government. Trump-era tariffs were retained with a few exceptions and extended against China, Buy American provisions were championed, and the United States’ approach to the WTO continued to veer between indifference and malign neglect. Under both Trump and Biden, the new paradigm of US foreign economic policy would be grounded in rejection of liberal economic orthodoxies, acute aversion to market-opening trade agreements and strategic competition with China.

President Biden put his own stamp on the demise of the Washington Consensus with Bidenomics — a project of sweeping state ambition that encompassed expansive macroeconomic policy, large-scale investment in infrastructure and manufacturing, trade and technology policies geared to strategic objectives and the active use of the state to guide economic activity in favoured industries. The revival of an American tradition of industrial policy via three signature pieces of legislation — the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021), the CHIPS and Science Act (2022) and the Inflation Reduction Act (2022) — would become one of the Biden administration’s proudest boasts.

Competition with China became central to the Trump administration’s national security strategy, albeit conditioned by the president’s erratic and highly personalised approach to policy making. The Biden administration cemented and extended this legacy, reinforced by a powerful bipartisan consensus in Washington on China policy. Sweeping US technology export controls, investment screening and outbound investment restrictions aimed at denying China access to advanced technologies would become a central thrust of this policy. Under the so-called “small yard, high fence” strategy, the United States sought to maintain as large a lead as possible in semiconductors, artificial intelligence (AI), quantum information and other strategic technologies.11

President Trump’s return to the White House has sanctified the overthrow of the liberal rules-based order. The Trump trade wars of 2025 have seen the US average effective tariff rate rise roughly sevenfold in less than a year (Figure 1.2). President Trump’s so-called “reciprocal tariffs” and his administration’s slew of bilateral trade deals continue to ripple through global supply chains and trading relationships as supporters celebrate and critics bemoan the demise of one international economic order and the uncertain birth of another.12

Figure 1.2. US average effective tariff rate (1820–2025)

The post-Cold War era of deep globalisation that hinged on binding countries into a US-led economic system is over. A shifting and indeterminate combination of tariffs, industrial policy interventions, investment screening, export controls and sanctions now forms the economic toolkit of a new Washington Consensus. A commitment to freer trade within a framework of multilateral rules has been banished as a cornerstone of US global economic engagement. The most-favoured nation principle — once a pillar of US leadership of the global trading system — has been discarded in favour of unilaterally-determined tariff rates and bilateral deals.

This new era of US economic statecraft has myriad (and often conflicting) policy goals. The reindustrialisation or ‘reshoring’ of manufacturing capacity is a key objective, alongside building more diverse and resilient supply chains. The reduction of economic dependencies on China serves as a key motivating factor, alongside measures aimed at denying the United States’ principal geopolitical adversary the commanding heights of technologies critical to national security and economic advancement. Forcing change in other countries’ economic and trade practices in the belief that this will drive down the US trade deficit continues to animate President Trump’s tariff crusade. The president’s highly transactional approach to deals and his embrace of tariffs as an all-purpose tool of geopolitical and economic leverage, and as a source of fiscal revenue, further complicate the already tangled links between US policy means and ends. Uncertainty is a feature (not a bug) of the Trump White House.

This report aims to unpack and understand the paradigm shift that has culminated in the second Trump presidency. It traces the origins and proximate drivers of this policy transformation, its evolving policy character and the contested global strategic environment in which it now operates. The implications for Australian economic policy are also explored.

1.2. Paradigm lost: The demise of the Washington Consensus

Two definitional questions are worth touching on briefly. What constitutes a paradigm shift? And why does this shift in US international economic policy justify this conceptual description?

Developed by Thomas Kuhn in the philosophy of science literature, the term was coined initially to describe a profound change or breakdown in intellectual systems that guide a particular domain of inquiry, when old systems and methods will not solve new problems.13 In political economy and public policy discourse, the notion gained currency where different constellations of economic ideas and policies arose in changing circumstances to command support eventually from both ends of the political spectrum.

Economist Dani Rodrik argues that paradigm shifts usually accompany crises that demand new answers and that a “new economic paradigm becomes truly established when even its purported opponents start to see the world through its lens.”14 He points to two notable examples in the modern political economy of Western liberal democracies. At its height following the Second World War, the Keynesian welfare state received as much support from conservative politicians as it did from social democrats. Similarly, while the turn towards economic liberalism in the context of 1970s stagflation (low growth and high inflation) was supported crucially by pro-market economists and politicians on the centre-right, it eventually became dominant with the incorporation of market-oriented policies into the governing agendas of centre-left political parties.

Together with others, Rodrik claims that new thinking on the need for a more active role for government in shaping the economy is now part of an emergent paradigm shift in mainstream economic thinking. This is seen as replacing “the market-liberal ‘Washington Consensus’, which for four decades emphasized the primacy of free trade and capital flows, deregulation, privatization, and other pro-market shibboleths.”15

Historian Gary Gerstle charts a similar trajectory but with the emphasis on the rise and fall of what he terms a “neoliberal political order.”16 Political orders are defined by Gerstle as based on a “constellation of ideologies, policies and constituencies” that shape politics in ways that endure for multiple election cycles. Like Rodrik’s economic paradigms, Gerstle associates political orders in the United States — in this case, the New Deal and neoliberal orders — with “the ability of its ideologically dominant party to bend the opposition party to its will.” He casts Ronald Reagan as the “ideological architect” and Bill Clinton as “key facilitator” of a neoliberal order that took shape in the 1970s and 1980s and achieved dominance in the 1990s and first decade of the 21st Century, before fracturing in the second decade.

For a new generation of US political actors and policy thinkers, an approach to China that prioritised engagement, closer economic ties and global trade rules is now seen as naïve and woefully inadequate in an era of superpower rivalry and weaponised interdependence.

The new Washington Consensus carries the hallmarks of a political-economic paradigm shift forged from a confluence of international and domestic forces. Evolving policy ideas and tools of state activism reflect a mix of structural drivers and events, often highly contingent ones, arising from long-run economic trends, shifting global power dynamics and domestic political disruptions linked to an American social contract frayed by sweeping economic and socio-cultural change. The upshot is that politicians on both the left and the right, as well as thinkers and activists across the US political spectrum, have repudiated the paradigm of economic liberalism and market-led globalisation in favour of a more statist, nationalist and security-oriented approach to international economic policy.

The structural rise of China, its progressive dominance of key manufacturing sectors and technologies and its more assertive grand strategy under Xi Jinping have catalysed a profound rethink in Washington about the economic underpinnings of US power.17 Globalisation and China’s model of state capitalism are seen universally within the US political system as hollowing out US manufacturing and destroying the livelihoods of millions of workers.18 For a new generation of US political actors and policy thinkers, an approach to China that prioritised engagement, closer economic ties and global trade rules is now seen as naïve and woefully inadequate in an era of superpower rivalry and weaponised interdependence.19

Donald Trump served as the indisputable lightning rod and agent of change in the shattering of the old Washington Consensus. Joe Biden would become co-author of an emergent new consensus on state activism, notwithstanding the polarisation and hyper-partisanship that beset modern US politics. Trump’s victory at the 2024 presidential election consolidates a historical transformation in US international economic policy and in the global economic order.

1.3. Outline of this report

The demise of the old Washington Consensus and the United States’ retreat from global economic leadership can be traced to structural shifts in the global economy, reordered power relations, specific economic shocks and their consequences filtered through domestic political agency and policy ideas. Section 2 argues that a combination of internal and external pressures shattered the political foundations of the old Washington Consensus in the early 21st Century, leading in turn to a crisis in the US trade policy regime. It places particular emphasis on the intersection of a prolonged period of modest growth in living standards among middle-class and low-wage American workers and the ‘China shock’ with its concentrated effects on US manufacturing employment.

The global financial crisis and the Great Recession magnified the political and ideological backlash against liberal economic policies, opening the door to Donald Trump’s assault on trade and globalisation. A more powerful, assertive and ambitious China under Xi Jinping further assailed prevailing assumptions of US grand strategy in the second decade of the 21st Century. Structural rivalry with China would henceforth become a binding agent for a new era of US economic statecraft.

Section 3 examines the paradigm shift in US policy in more detail, along with the instruments that have given it expression. The revival of tariffs, industrial policy and other forms of state intervention amounts to a rejection of past economic orthodoxy by the post-Reagan Republican Party and economic nationalists on the right and by Democrats and others on the progressive left critical of the party’s accommodation with neoliberalism. Technology competition with China is emblematic of this new Washington Consensus, as national security concerns have driven demands for the decoupling of US and Chinese technological ecosystems.20

As outlined in section 4, pressures that have led governments worldwide to embrace more state-directed, interventionist and security-focused economic policies are far from simply Made in America. By the early years of the 21st Century, China’s model of state capitalism presented an unprecedented challenge to the liberal foundations of the US-led global economic order. The rise of what Farrell and Newman call the “economic security state” now stands as a defining feature of a more multipolar, less rule-bound global environment.21 Across the Global West and the Global South, governments have adopted new strategies and tools aimed at protecting vital industries, boosting growth and competitiveness, accelerating the green transition and supporting national sovereignty and security objectives.

This paper contends that the risks of geopolitical upheaval and economic fragmentation are such that Future Made in Australia requires significant rebalancing away from the green transition and towards strategic objectives.

Section 5 explores the implications for Australia of the demise of the postwar liberal economic order and the rise of a new era of economic statecraft. A middle power with enduring interests in an open, rules-based trading system, Australia finds itself navigating the most turbulent global environment in decades, marked by strategic competition between its cornerstone strategic ally (the United States) and its major trading partner (China).22

The Australian Government’s main policy response to heightened geopolitical risk and geoeconomic fragmentation is the Future Made in Australia agenda.23 Announced in 2024, it has the dual objectives of embedding Australia in a low-carbon global economy and supporting greater economic resilience and security.

This paper contends that the risks of geopolitical upheaval and economic fragmentation are such that Future Made in Australia requires significant rebalancing away from the green transition and towards strategic objectives. It offers a series of recommendations in connection with the wider renovation of Australian economic statecraft, one that strives for a new marriage between economic rationalism and state capacity geared to Australia’s unique strategic circumstances and national interests.

2. The anatomy of a paradigm shift

Support within the US political system for the post-Cold War Washington Consensus cracked in the first decade of the 21st Century before crumbling in the second decade. The radically reshaped US foreign economic policy that would emerge has its roots in long-run economic trends, changes in global power dynamics, specific shocks and domestic political agency and ideas tied to a powerful backlash against globalisation, open trade and engagement with China.

This study pinpoints the intersection of two variables tied to the US labour market as having particular significance in understanding this backlash. The first is relatively sluggish growth in living standards at the bottom and middle of the US income distribution over several decades, against a backdrop of steeply higher economic inequality. The second is the concentrated hollowing out of US manufacturing jobs in the 2000s in the wake of China’s rapid rise as a global manufacturing powerhouse.

These forces gained added political potency from the GFC and the Great Recession. The financial hardship and frustration felt by millions of Americans amid the greatest economic downturn since the Great Depression opened the door to new political entrepreneurs and narratives of grievance. This discontent would ripple through both major US political parties in the 2010s, shattering the fragile coalition that helped to sustain support for open trade and US leadership of a liberal economic order.

China’s assertion of geopolitical power, buttressed by its spectacular economic rise, would become a more prominent source of disruption in the second decade of the 21st Century. China’s expansive grand strategy under President Xi Jinping provided the coup de grâce to the old Washington Consensus, as the United States sought to respond to economic discontent at home and a rising great-power challenger abroad. In summary, economic stress in the American heartland, fractured political support for globalisation and the rise of a more assertive, ambitious China go a long way to explaining the demise of the old Washington Consensus and the eventual rise of a new Washington Consensus.

Several conclusions follow from this analysis. First, Donald Trump’s trade wars and Joe Biden’s industrial policy have similar structural origins. Second, while economic trends and shocks carry large explanatory weight in this account, political agency and ideas matter in understanding the timing and tools of policy transformation. Third, the scale and character of China’s rise and its mercantilist model of state capitalism subjected the liberal foundations of the postwar economic order to acute strain separate from Washington’s policy response.

2.1. Middle-class stagnation and its discontents

Faltering faith in the “American Dream” — the promise of each generation doing better than the one before it — helps to connect Donald Trump and Joe Biden to the demise of the old Washington Consensus. It is no coincidence that every successful presidential campaign in the past two decades — from Barack Obama in 2008 to Donald Trump in 2024 — has tapped a mood of economic frustration and anxiety tied to a narrative of hard-working Americans getting a raw deal from some mix of powerful economic elites, a broken social contract or unfair foreign economic practices.

As a rising star in the Democratic Party, Illinois Senator Barack Obama chose “Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream” as the subtitle of his 2006 bestseller, The Audacity of Hope.24 President Obama won re-election in 2012 tagging his Republican opponent Mitt Romney as a consulting agent for outsourcing multinationals.25 Announcing his bid for the presidency in 2015, Donald Trump told supporters: “Sadly, the American Dream is dead. But if I get elected president, I will bring it back bigger and better and stronger than ever before.”26

The Democratic Party’s 2020 presidential election platform pledged a future Biden administration to forging a “new social and economic contract” with Americans, with Republicans accused of “rigging the economy in favour of the wealthiest few and the biggest corporations.”27 Pitching his plan to voters in 2023, President Biden portrayed Bidenomics as “just another way of saying: Restore ‘the American Dream’.”28 Donald Trump would again assail Democrats for killing the American Dream in the run-up to the 2024 election.29

This theme — an American Dream no longer living up to its former promise — has been explored by numerous analysts and commentators from a variety of angles. In Ours Was the Shining Future: The Story of the American Dream, David Leonhardt of the New York Times laments a country “where most people’s incomes and wealth have grown slowly, where inequality has soared, where life expectancy has stopped increasing for most of the population.”30 Historian Walter Isaacson describes the decline of the American Dream as nothing less than “the most important social issue of our era.”31 Writing in 2017, conservative columnist David Brooks singled out “middle-class wage stagnation” as “the biggest economic fact driving American politics.” It explains, he argued, “why the Democratic Party has moved from the Bill Clinton neoliberal center to the Bernie Sanders left. It explains why the Republicans have moved from the pro-market Mitt Romney right to the populist Donald Trump right.”32

No one statistic or data series captures the deep-seated economic frustration that has reshaped US politics over recent decades.

No one statistic or data series captures the deep-seated economic frustration that has reshaped US politics over recent decades. Indeed, claims about middle-class stagnation are contested by some analysts who point to periods of robust economic activity, per capita income growth and living standards superior to earlier decades.33 Yet the dominant picture that emerges from a variety of sources is of a large and growing share of US households finding it difficult to attain financial security and a middle-class lifestyle in the late 20th and early 21st Centuries. Narratives proclaiming the end of the American Dream have found fertile soil in weak earnings growth for workers without a college education, a squeezed middle class, increased income and wealth inequality and reduced social mobility.

Labour market studies point to modest wage growth across the middle and bottom of the US income distribution, with some cohorts experiencing flat or declining real wages for long periods at a time. Figure 2.1 illustrates trends in median wages and family incomes — the 50th percentile — relative to more robust overall per capita income growth. It shows real disposable per capita income growing by 1.8% per annum over a period approaching four and a half decades. Real median family income grew more modestly at 0.8% per annum, while median real earnings inched up even more slowly at only 0.2% per annum.

Figure 2.1. US income and wage growth (1979–2024)

In the wake of 1970s stagflation, the data show relative stagnation in earnings in the 1980s, some growth in the second half of the 1990s and further income stagnation in the 2000s, before the severe impact on households of the GFC and the Great Recession. A period of steady improvement in earnings growth from the mid-2010s would be punctuated at the start of the next decade by the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent spike in inflation.34

Analysis by the US Treasury in 2023 found that median real wages increased by 8% over the 40-year period between 1979 and 2019, with annual growth of only 0.2% per year.35 Real median family income, including earnings of other family members, grew marginally better at 0.6% when account is taken of large increases in female employment and a rise in dual-earning households. The Obama administration’s Council of Economic Advisers concluded similarly that median real wages rose by only 8% between 1979 and 2014, while wages at the 10th percentile declined slightly.36

The deterioration in economic prospects has been most dramatic for less educated men in the United States. A 2019 study, for example, found that real hourly earnings for the typical 25- to 54-year-old man with only a high school education declined by 18.2% between 1973 and 2015.37 By contrast, real hourly earnings for college-educated men increased substantially.

Reinforcing a picture of a squeezed middle class is the discrepancy between the pace of income growth, on the one hand, and rising costs of housing, health care, education and childcare, on the other. These costs have consistently risen faster than median incomes, taking up a progressively higher share of household budgets. Studies show that health, housing and education are now a much larger burden than they used to be for the middle class, meaning middle-class aspiration has become relatively more expensive.38 Health and housing are by far the largest categories, together making up close to 40% of total household expenditure. In the case of housing, median house prices in the United States have grown more than three times the rate of household income since the mid-1970s.39

Efforts to sustain middle-class lifestyles have been financed in part by higher household debt, with debt-to-income ratios more than doubling since the 1970s, while also limiting the room for savings.40 Other indicators of middle-class success have similarly deteriorated over time, with evidence that incomes have become more volatile, the amount of time spent on vacation has fallen and middle-class Americans appear less prepared for retirement.41

Rising inequality

Trends in income and wealth inequality in the United States are cited regularly as evidence that the middle class and the bottom 20% of households are worse off than they used to be, though such indicators rely necessarily on relative measures of economic well-being. Despite signs of stabilisation in recent years, long-run trends show income growth for most low-wage and middle-class households failing to keep pace with that of the top 20% of households, while their shares of total income and wealth have fallen.42

Despite signs of stabilisation in recent years, long-run trends show income growth for most low-wage and middle-class households failing to keep pace with that of the top 20% of households, while their shares of total income and wealth have fallen.

Focusing on wage quintiles, a 2017 Brookings Institution study of the period from 1979 to 2016 found that real wages fell by 1.0% for the bottom 20%, rose by 0.8% for the lower-middle quintile and by 3.4% in the middle quintile.43 By contrast, wages rose by 11.5% in the upper-middle quintile and by 27.4% in the top quintile (Figure 2.2). A picture of the middle class falling further behind the top 20% of households is apparent also when taxes and transfers are taken into account. On this basis, Congressional Budget Office analysis in 2019 found that the middle three household income quintiles experienced total income growth in real terms of 28% from 1979 to 2014. The top 20% saw their incomes grow by 95% over the same period.44

Figure 2.2. US real wages by wage quintile (1979 and 2016)

Labour market studies have sought to explain the steep and persistent rise of earnings inequality and the erosion in the economic prospects of less educated workers in the United States and in other advanced economies. A broad consensus among economists points to the role of skill-biased technological change as the principal factor explaining sluggish wage growth at the bottom of the income distribution and rising wage inequality in the 1980s and 1990s. The revolution in computer and information technology is pinpointed as driving rising demand for skilled workers and a marked increase in the ratio of earnings of those with a college degree over those with a high school degree.45

Widely-cited research on the US experience found that about two-thirds of the rise in earnings disparities between 1980 and 2005 was accounted for by the increased earnings premium associated with higher education and cognitive ability.46 Other factors — globalisation and competition from developing countries, immigration and labour market institutional arrangements (including minimum wage settings and the role of unions) — tend to be grouped as secondary, even if they gain greater prominence in political debates.

Wealth trends also show marked divergence between low-to-middle-class and higher-income households. Drawing on Federal Reserve Board data, Brainard concludes that the wealth of middle-income households, adjusted for inflation, increased by an average of about 1% per year over three decades from 1989.47 Meanwhile, the average wealth of households in the top decile of the income distribution rose three times faster on average, more than doubling over the period. As a result, the share of total wealth held by the 30% of households between the 40th and 70th percentile of income fell from 19% to 13%. The 10% of households with the highest incomes saw their share of national wealth climb from 47% to 57% — more than the remaining 90% of households combined.48

The GFC and the associated housing crash had a particularly severe impact on middle-class financial buffers. Millions of Americans lost jobs and homes in the Great Recession. Median incomes failed to recover to pre-crisis levels until the middle of the following decade. Impacts on wealth across middle and low-income America were even more pronounced. Brainard notes that more than a decade after the financial crisis, middle-income US households still had not recovered the wealth they lost in the Great Recession, while lower-income families had a wealth shortfall of 16% compared with before the crisis (Figure 2.3).49

Figure 2.3. US change in household wealth, by income percentiles (2007–2018)

Measures of intergenerational mobility have confirmed fears of an American Dream increasingly out of reach. Research by Harvard’s Raj Chetty using tax records finds that Americans born in 1940 had a 92% chance of obtaining a higher real income than their parents. For Americans born in 1980, that figure had fallen to around 50%.50 Carol Graham of the Brookings Institution finds a widening prosperity gap translating into a widening gap between peoples’ beliefs and aspirations, with a large gap between the middle and top quintiles of the income distribution when it comes to optimism about the future and the idea that hard work gets you ahead.51 Polling data also points to increased economic frustration, dashed expectations and declining faith in the American Dream. A Wall Street Journal/NORC survey in November 2023 reported, for example, that only 36% of American voters regarded the American Dream as still holding true. This figure was down from results of similar surveys in 2012 (53%) and 2016 (48%).52

On several measures, the US economy has performed strongly in the past decade compared with other advanced economies. Most groups experienced real income gains, at least prior to COVID-induced inflation, with some evidence of convergence in income and wealth disparities. Yet the longer-term trend remains one of Americans becoming less optimistic about future real income gains, with the measured drop most pronounced among middle-income households.53

2.2. Globalisation and the “China shock”

The role of international trade and globalisation in shaping the economic fate of the US middle class has long been a contested issue, even as the Washington Consensus held to a view of liberal trade relations providing clear benefits to the US economy and the vast majority of Americans. China’s emergence as a global manufacturing superpower would shake this prevailing paradigm, including in elite policy circles, with enduring consequences for US politics and international economic policy.

The end of the Cold War and the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe saw US grand economic strategy enter a new phase. The failure of socialism and inward-looking development strategies led a host of nations to embark on liberalising economic reforms by the late 1980s. For US policymakers, the opportunity to lock in and extend market access gains in fast-growing emerging economies meshed neatly with the policy prescriptions of the Washington Consensus.

In February 1991, the leaders of the United States, Mexico and Canada announced their intention to start negotiations on a free trade agreement. This was an opportunity for the United States to improve cooperation with its southern neighbour and to secure new market access with few concessions. With most of its exports already entering the United States duty-free, Mexico would be called on to do most of the liberalisation. Even so, what became the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) touched off “one of the most contentious and divisive trade-policy debates in US history.”54

Pro-trade business groups faced off against a coalition of forces including labour unions, environmental groups, human rights activists and domestic producers threatened by Mexican competition. With its sharpened focus on winners and losers from globalisation, NAFTA prefigured later US trade battles. The United States was negotiating a major bilateral trade agreement with a developing country for the first time. Clear divisions over trade were apparent not simply between US political parties, but within them as well. And, with the Cold War over, the debate over NAFTA showed that traditional foreign policy arguments no longer held the same traction in countering demands from constituencies opposed to liberal trade.

While initiated by Republican President George HW Bush, it fell to his successor, Democrat Bill Clinton, to navigate NAFTA’s congressional passage. During the 1992 election campaign, Clinton was equivocal on free trade, though he eventually supported NAFTA contingent on stronger labour and environment protections.55 Opposition to the agreement conspicuously brought energy into the insurgency campaign for the Republican Party nomination waged by Pat Buchanan, as well as the third-party candidacy of H Ross Perot. Perot would go on to win 19% of the total vote in 1992, the strongest showing by a third-party candidate in 80 years.56

On taking office in January 1993, President Clinton used a major speech to set out the case for continued US international economic leadership in striving to “open other nations’ markets and to establish clear and enforceable rules on which to expand trade.” The United States, he argued, “must compete, not retreat.”57 However, the union-led campaign in opposition to NAFTA within the Democratic Party forced the Clinton administration to rely heavily on Republican votes in the House to secure passage in November 1993 with a margin of 234 to 200 votes. Democrats in the House voted 156 to 102 against the agreement. The Senate voted 61 to 38 in support of the legislation.58

Success on NAFTA, albeit hard fought, provided impetus for the Clinton administration to conclude the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations in December 1993. After seven years of negotiations, this saw the expansion of trade rules into new areas and brought developing countries more squarely into the multilateral trading system. The Uruguay Round agreement placed new disciplines on agricultural trade policies, extended rules in areas such as services and intellectual property protection and established the World Trade Organization (together with a more binding dispute-settlement system). It would mark the high point of US efforts to forge a genuinely global liberal economic order shaped by American geopolitical and commercial interests. With US negotiators playing a lead role in concluding the round on American terms, opposition within Congress remained relatively muted when implementation legislation came to a vote in November 1994.

Two factors in roughly equal measure drove deeper global economic integration in the 1990s. The first was reformist liberalisation policies and international agreements such as the Uruguay Round that reduced government-imposed barriers to the movement of goods, services and capital. The second was new technologies that markedly reduced the costs of transport and communications.59 These dual forces came together most powerfully in the transformation of China and its place in the global economy.

The “reform and opening” era initiated by Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s propelled a dramatic acceleration in China’s economic growth and rapid expansion in its foreign trade. For roughly three decades from the start of the reform era, China’s economy grew at more than 10% a year, driven largely by rapid manufacturing development. The shift from economic self-reliance to export-led growth in manufactures saw the volume of China’s exports grow at 13% a year between 1980 and 1990 and then at 11% per annum from 1990 to 1999.60

Between 1991 and 2013, China’s share of world manufacturing exports rose from 2.3% to 18.8%, with the manufacturing sector averaging 88% of China’s merchandise exports over this period. China’s share of world manufacturing value added increased sixfold, from 4.1% to 24.0% (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4. Share of global manufacturing value added (1995–2022)

In the early 21st Century, China surpassed Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy, on its way to becoming the world’s largest manufacturing producer and exporter by the end of the 2000s. China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 proved pivotal to its deep integration into the global economy and to subsequent developments in US-China relations. Under the accession deal, China agreed to slash tariffs and certain non-tariff barriers while the United States agreed to phase out select textile quotas and, importantly, to grant China permanent most-favoured-nation trade status.

The Clinton administration made the case for China’s accession using both political and economic arguments. Speaking in March 2000, President Clinton argued that WTO membership “will not create a free society in China overnight or guarantee that China will play by global rules. But over time, I believe it will move China faster and further in the right direction and certainly will do that more than rejection would.”61 Describing the agreement as “the equivalent of a one-way street,” Clinton stated that it “requires China to open its markets — with a fifth of the world’s population, potentially the biggest markets in the world — to both our products and services in unprecedented new ways.”

Business groups, US multinationals and agricultural producers lined up to support permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) with China. In May 2000, the House of Representatives voted to award China PNTR, with 73 Democrats joining 164 Republicans to pass relevant legislation. In September, the Senate approved PNTR legislation by a vote of 83 to 15. This eliminated the ritual, in place since the Carter administration normalised bilateral relations in 1979, whereby Congress needed to formally approve normal trade arrangements with China each year.

For the better part of two decades from the early 1990s, rising trade with China was responsible for nearly all the expansion of US imports from low-income economies. Figure 2.5 shows the sharp rise in US imports from China after WTO accession in 2001, with a brief fall associated with the GFC. From less than 8% in 2000, the share of US imports from China grew to almost 20% by the end of the decade, with concentrated effects in the US manufacturing sector.

Figure 2.5. US imports from China (1990–2024)

China’s surging export growth accelerated the decline in US manufacturing employment. The relative decline in manufacturing employment is common to all advanced economies. Prior to the 1990s step-change in globalisation, the share of manufacturing jobs in total US employment had fallen from around 30% in the late 1940s to roughly 15% by the time NAFTA came into force. As Irwin observes, however, the import and employment shock on the US manufacturing sector in the years following China’s accession to the WTO was significantly larger in magnitude than Japan’s in the 1980s or Mexico’s in the 1990s.62

Enter Autor, Dorn and Hanson

Coining the term “China shock”, economists David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson examined the scale, geographic dimensions and localised impacts on US manufacturing in a series of academic papers beginning in 2013. Their findings challenged conventional economic wisdom that regarded losses from trade competition as diffuse and diminishing in a relatively short amount of time. The China shock, they found, exerted immense pressure on many US manufacturing communities in a way that was significant, highly concentrated and long-lasting.63

In their seminal 2016 paper, Autor and his colleagues concluded that surging manufacturing imports from China between 1999 and 2011 displaced around a million US manufacturing jobs, with spillovers that cost up to 2.4 million jobs in total. They attributed around a quarter of the decline in US manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2007 to the China shock. Employment fell sharply in industries most exposed to import competition, especially in relatively low-technology, labour-intensive sectors such as textiles, clothing, footwear and commodity furniture. These sectors had already experienced declines in employment due to automation and shifts in consumer demand, but the surge in imports from China greatly exacerbated these trends with large adverse impacts on local labour markets in the US Midwest and the South.

Figure 2.6 shows the sharp decline in US manufacturing employment associated with the China shock. In the period between 1999 and 2007 — regarded as ‘peak China shock’ — US manufacturing jobs fell by 22%, from 17.9 million to approximately 14.2 million jobs. The Great Recession saw a further marked decline before a period of modest recovery in the 2010s.

Figure 2.6. US manufacturing employment (1979–2024)

Many of the workers who lost jobs struggled to find reemployment in export sectors or other manufacturing industries and lacked the geographic mobility to move to regions that were creating jobs. Employment options among displaced workers were often confined to low-wage service sector jobs, while a cohort dropped out of the labour force altogether. Follow-up studies confirmed that offsetting employment gains often failed to materialise, with wages and labour-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates elevated for at least a decade after the China shock.64

Adverse outcomes were more acute in regions that had fewer college-educated workers. Contrary to the expectation of labour markets adjusting within a reasonable period, the opposite was found to be the case among households under economic duress. The knock-on effects from the China shock were seen to go well beyond job churn and displacement. Earnings for low-wage workers fell, children became more likely to live in poor, single-parent households and “deaths of despair” among working-age adults — primarily due to drug overdoses among men — increased.65

The China shock research, as economics writer/blogger Noah Smith has written, uncovered a level of disruption and faltering adjustment far more severe than conventional economic wisdom expected. The analysis, he observed, was “like a meteor crashing into the econ[omics] profession. Prior to Autor et al. (2016), ‘free trade is good’ was the most unshakeable consensus in the economics profession; after the paper came out, that consensus was shattered.”66 The ripple effects of this economic disruption on US politics and the terms of debate over trade and globalisation would be even more far-reaching.

2.3. America First meets the Sullivan Doctrine

The China trade shock, on top of the long-run squeeze in living standards felt by low and middle-income Americans, cracked the foundations of US economic grand strategy in the first decade of the 21st Century. The economic and social scarring caused by the GFC and the Great Recession widened these cracks further with major political consequences.

The globalisation backlash was not immediate. The crisis in the US trade policy regime emerged over time. Trade issues did not figure prominently in the 2008 presidential election. Contenders for the Democratic party nomination, Senators Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, sparred over who would be tougher in defence of US workers in the primaries, but neither sought to make trade a major election issue. As the party’s nominee, Obama attacked trade agreements initiated by President George W Bush, voicing traditional Democrat concerns about weak environmental and labour standards. For the most part, however, his views on trade remained ambiguous.67

The China trade shock, on top of the long-run squeeze in living standards felt by low and middle-income Americans, cracked the foundations of US economic grand strategy in the first decade of the 21st Century.

The immediate challenge facing President-elect Obama at the close of 2008 was collapsing economic activity in the wake of the financial crisis. Unemployment in the United States climbed to 7.4% in December 2008, up from 5% a year earlier, on its way to reaching 10.1% in October 2009.68 Obama drew on an experienced economics brains trust “rooted in the centrist, market-friendly economic philosophy of the Clinton Administration” to help formulate his economic rescue plan.69 These personnel decisions reinforced continuity on international economic policy and, while Obama remained cautious on trade throughout his first term, the relative absence of new protectionist measures in response to the Great Recession signalled no obvious break from the past.

Similarly, the Republican Party through the turn of the decade retained a disposition towards freer trade. After gaining control of the House of Representatives at the 2010 midterm elections, congressional Republicans pushed to resurrect Bush era trade agreements with Colombia, South Korea and Panama that had languished since 2008. With mainly Republican support, the House and Senate passed the agreements in October 2011.70

After winning the 2012 presidential election, and despite resistance within his own party, President Obama showed greater willingness to embrace pro-trade initiatives. With global trade talks under the Doha round stalled, the administration turned its focus to regional agreements. The major play — part of a broader strategic ‘pivot’ towards Asia — was the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Negotiations covered a broad suite of trade and regulatory issues, ultimately encompassing 12 partner countries — with the notable exception of China. In 2013, the Obama administration also embarked on new negotiations with the European Union on a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership with a focus on improving regulatory cooperation.

Relying heavily once again on Republican votes, the Obama administration secured congressional support for new trade-promotion authority in June 2015. Negotiations on TPP concluded later that year, though talks with the European Union proved more difficult given unwillingness on both sides to compromise on health and environmental standards.71 Away from government negotiations over market access and subsidies, however, the political underpinnings of US foreign and trade policy had undergone a seismic shift.

The looming 2016 presidential election provided a platform for two self-styled political outsiders — Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders — intent on assailing Washington elites and overthrowing the policy directions of both major parties. Both the Trump and Sanders insurgencies gave voice to deep currents of grievance and resentment in US society located among those who felt left behind by rapid economic and socio-cultural change. Many saw themselves as victims of a system rigged in favour of the rich and powerful. Both insurgents challenged establishment political machines that acted as gatekeepers of party standard bearers and policy platforms. Both cast trade agreements and globalisation as major sources of economic dislocation and middle-class anxiety, though Trump would prove ultimately to have the most potent political message.

The Trump insurgency found fertile soil in the Tea Party revolt during the first Obama administration. This grassroots movement arose as a backlash against Obama initiatives during the Great Recession, portrayed as coming at the expense of middle-class voters forced to pick up the tab. Lightning rods included a plan to shield low-income homeowners from foreclosure and President Obama’s Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), a program seen as forcing some Americans to pay higher premiums and co-payments so those without insurance could afford it. Another Tea Party cause celebre was the perceived illegitimate use of government funds and services by illegal immigrants.72

Tea Party groups helped to nominate candidates for the House and Senate in 2010 midterm elections. After Republicans won Congress but failed to repeal Obamacare, the movement turned its sights on the GOP establishment. To political analyst John Judis, the Tea Party is best viewed as a “rightwing rather than a leftwing response to the Great Recession and to neoliberalism.”73 The animating ethos, familiar to populist movements in the United States and elsewhere, sprang from a sense that America was in decline and that the instincts of ordinary Americans were wiser and nobler than those of experts and elites. Trade and globalisation may not have been central to the Tea Party revolt, but the broader sentiment it embodied prefigured Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again (MAGA) campaign and support base.

“They’re laughing at us”

The Trump narrative on trade, honed over almost 30 years, mixed elements of grievance, betrayal, conspiracy and fact. Trade deficits supposedly meant that the United States was being ripped off by its trading partners, including its closest allies. The United States was bearing an unfair share of the burden of global security and its open market contrasted with other countries that did not play by the rules. Trade agreements — from NAFTA to the WTO — were symbols of a corrupt ‘globalist’ establishment pursuing utopian international projects and furthering its own interests at the expense of ordinary Americans.

For Trump, no one embodied this elite failure more clearly than his Democrat opponent in the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton. On the campaign trail, Trump attacked the former secretary of state for unleashing a “trade war against the American worker when she supported one terrible trade deal after another — from NAFTA to China to South Korea.”74 He made a point of zeroing in on Ms Clinton’s previous support for TPP as the “gold standard” in trade agreements, as did her Democrat challenger Bernie Sanders. The Democrat front-runner would abandon the Obama administration’s Asian trade initiative in late 2015, a sign of an increasingly toxic trade debate and the collapsing centrist pro-trade coalition in Washington under the weight of attacks from the populist right and the progressive left.75

Trump’s America First platform pledged to close trade deficits, bring manufacturing jobs back to the United States and put an end to one-sided trade agreements. As well as promising to withdraw the United States from TPP and renegotiate NAFTA, Trump spoke repeatedly of his determination to apply stiff tariffs to countries that cheat, especially China. “China has taken our jobs, our factories, our money. They’re laughing at us,” Trump told his supporters. He vowed to declare China a currency manipulator, bring trade cases against China and impose heavy tariffs on Chinese goods to deliver American workers a level playing field.76

By this time, the cracks in the old Washington Consensus were emanating from strategic vectors as much as economic ones, as China loomed as a full-spectrum rival to the United States with implications that went far beyond trade deficits and manufacturing jobs. The GFC again marks an inflection point when viewed through the prism of Chinese grand strategy.77 An emboldened China emerged more confident in asserting its power and influence around an expanded set of international interests and objectives. No longer would it conform to Deng Xiaoping’s foreign policy dictum of “hiding capabilities and biding time.” China would use every element of statecraft to expand its regional and global footprint, armed by the conviction that “the East is rising and the West is declining.”78

Through a series of political, diplomatic, economic and military initiatives, China set about building the foundations for regional hegemony in Asia and a more central role in global affairs. The coming to power of Xi Jinping in 2012 serves as a further landmark in Beijing’s projection of regional and global power. Internally, Xi moved to consolidate and centralise state power and affirm Chinese Communist Party (CCP) control over the economy with a renewed commitment to Marxist-Leninist ideology.79 Ensuring private firms complied with the goals and diktats of the Party-state necessarily took priority over further moves towards economic liberalisation as market-driven growth gave way to a resurgence of the role of the state in resource allocation.80 In the words of former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, Xi’s personal brand of Marxist nationalism “pushed politics to the Leninist left, economics to the Marxist left, and foreign policy to the nationalist right.”81

Externally, Xi’s declared quest for the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” embraced the realisation of “unshakeable” territorial and sovereignty ambitions (including in relation to Hong Kong and Taiwan), expansive military, economic and technological goals, the displacement of the United States as the preeminent power in the Indo-Pacific region and the transformation of the international order to one more closely aligned with Chinese values and norms. Promoting a distinct “Chinese path to modernisation” lay at the core of Xi’s vision. China’s more assertive grand strategy took on tangible form at a speed and scale with few historical comparisons.

The flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, promised massive Chinese investment in infrastructure to promote connectivity between China and countries in Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa. The BRI became the leading example of a wider strategy geared towards building new economic and financial institutions as a counter to the Western-led institutions of the post-war order.82

China’s quest for greater military power and presence saw accelerated investments in new aircraft carrier groups, amphibious vessels and overseas facilities. In 2013, China declared an Air Defence Identification Zone over the East China Sea. The following year, as part of its ambitions to become a maritime great power, China began building and militarising artificial islands in the South China Sea, while moving at the same time to establish its first official overseas base in Djibouti.83

The release of the “Made in China 2025” plan in May 2015 marked a new phase in China’s ambitions to lead the world in the development and manufacture of critical technologies of the so-called ‘fourth industrial revolution’.

The release of the “Made in China 2025” plan in May 2015 marked a new phase in China’s ambitions to lead the world in the development and manufacture of critical technologies of the so-called ‘fourth industrial revolution’. Large-scale state subsidies would henceforth be directed towards ten high-technology industries, including semiconductors, electric vehicle batteries, biotechnology and robotics, quantum computing and AI, with explicit targets for self-sufficiency. This was part of a comprehensive strategy that included the acquisition of foreign talent and technology through both licit and illicit means and a drive to embed Chinese standards through the BRI and international standard-setting bodies.84

Among more proximate triggers of Washington’s growing alarm were a series of cyber incidents on top of the large and growing list of complaints from US companies about Chinese cyber espionage and theft of intellectual property.85 In 2014, the US Department of Justice launched the first-ever public criminal action against state military personnel for hacking when it indicted five Chinese PLA officials for cyber-enabled economic espionage. In 2015, it was disclosed that hackers had gained access to the personal data of more than 22 million federal employees via the Office of Personnel Management. Though not formally attributed, intelligence assessments pointed towards China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) and affiliated entities.86

The Obama administration’s 2011 pivot towards Asia, designed to strengthen alliances, expand US military presence in the region and create new economic partnerships through the TPP, was in no small measure a response to China’s growing regional influence and ambitions. At the same time, the Obama administration remained committed to an engagement strategy that had been Washington orthodoxy since the 1970s as it sought to enlist Chinese cooperation on international challenges from the nuclear ambitions of North Korea and Iran to climate change.87 By the end of the Obama administration, however, the hope of China becoming more liberal, more market-oriented and more enmeshed in a US-led global order had faded from view. The geopolitical buttresses of the old Washington Consensus appeared as broken as the economic ones as China’s expansive ambitions reset the context for US grand strategy.

Donald Trump’s unexpected victory in 2016 would reshape the American political map and US international policy with lasting consequences. Trump’s victory was grounded, above all, in the shift of white working-class voters into the Republican column, including many who had voted twice for Barack Obama. At the 2016 election, the Republican candidate’s advantage among white working-class voters reached the unprecedented margin of 31 points.88 His crusade against globalisation, trade agreements and the loss of manufacturing jobs marked a defining element of Trump’s America First narrative and agenda.

Trump’s crusade against globalisation, trade agreements and the loss of manufacturing jobs marked a defining element of Trump’s America First narrative and agenda.

There is evidence to suggest it played a decisive role in his victory, especially given the concentrated demographic and geographic fallout from the China trade shock. Economic analysis showed that industries more exposed to China saw higher exit of plants, larger contractions in employment and lower incomes for affected workers. The local labour markets that were home to these industries endured greater job losses and larger increases in unemployment, nonparticipation in the labour force and greater uptake of government transfers. A consistent finding from the China shock literature is that white non-college-educated males, a core constituency of Donald Trump, experienced particularly adverse employment outcomes.

Extending their economic analysis to political variables, Autor and his colleagues found exposure to rising import competition from China to be “strongly associated with an increased Republican vote share and political realignment.”89 Congressional districts where competition from Chinese imports increased rapidly became more politically polarised after 2008 as “ideologically strident” candidates replaced moderates, with net gains by anti-trade GOP representatives. Other studies showed Republicans becoming more likely to incorporate anti-China trade messages into communications with voters at the same time.90

Analysis by the Wall Street Journal prior to the 2016 election found that in Republican presidential primary races, Donald Trump won 89 of the 100 counties most affected by competition with China.91 Though no more than suggestive, a counterfactual analysis of closely contested states by Autor and his coauthors following the election concluded that a 50% lower trade shock (growth in Chinese import penetration) would have seen Hillary Clinton win Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania and hence a majority in the electoral college.92 Analysis of voter surveys also links Trump’s victory in 2016 directly to economic shocks from globalisation and the inability of the US political establishment to respond adequately.93

Trump as change agent