The 'State of the Union' refers to the constitutionally-mandated duty of the US president to keep the House of Representatives and Senate abreast of the current conditions of the United States and the president's upcoming legislative agenda.

Article II, Section 3, Clause 1 of the US Constitution states that the president “shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient”.

Interpretations of how this should be met have changed over the life of the republic, but one consensus has been that it should be a yearly update. Although presidents often address a joint session of Congress in their first inauguration year, it's considered too soon for a State of the Union address to be delivered. The first such fulfilment of the constitutional duty generally occurs in January of their second year.

The transformation of the State of the Union

Initially, the presidential fulfilment was known as the ‘Annual Message’. Both presidents George Washington and John Adams delivered the first 12 annual messages directly to a joint sitting of the Congress, but Adams' successor Thomas Jefferson saw it as extraneously timely and too kingly to dictate a speech to the Congress rather than giving congressmen requisite time to digest and officially respond to a written message. This remained the norm until President Woodrow Wilson revived the practice of delivering the message to the Congress in person in 1913. Since 1947 the address has been officially termed ‘the State of the Union’.

The tradition has since often strayed from the ceremony of today, but with the advancement of broadcast technology it has steadily transformed into a message directed at the nation as well as the Congress. The first radio broadcast of an address was Calvin Coolidge’s in 1923 and the first televised address was Harry Truman’s in 1947. Truman (1946, '53), Eisenhower (1961) and finally Carter (1981)1 were the last to revert to written-only messages; Franklin D. Roosevelt (1945) and Eisenhower (1956) both wrote to Congress and addressed the nation separately on the radio. In 1965 Lyndon B. Johnson scheduled the address in the evening to reach a wider television audience, which became the norm (Franklin Roosevelt had trialled this in 1936 for radio listeners). Nixon (1972, '73, '74) and Carter (1978, '79, '80) delivered both an oral and written message. In 2002, George W. Bush’s address was the first to be webcast.

In 1966 Republicans began the unofficial practice of issuing a formal response to the State of the Union address. Both Democrats and Republicans have overwhelmingly maintained this tradition by having members of Congress from the opposition party deliver a televised rebuttal shortly after the president’s address. These generally garner considerably less interest than the president’s address, but are seen as a testing ground for prospective candidates. Presidents Bill Clinton, Gerald Ford and George W. Bush, Speakers Pelosi and Ryan and 2016 candidates Marco Rubio and Tim Kaine have all given such responses.

State of the Union ratings

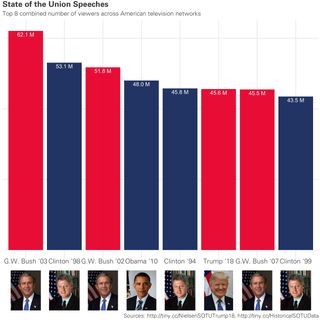

For a ratings-driven President Trump, the State of the Union offers a uniquely large platform to showcase his leadership. It is the only annual occasion that offers the president the chance to combine several important constitutional roles: chief of state, chief executive, chief diplomat, commander-in-chief and chief legislator. Along with the Super Bowl, Grammys and Oscars, the State of the Union is one of the highest-rating billings on the television calendar, particularly in the early years of a presidency. President Trump’s first State of the Union drew 45.6 million viewers domestically, which the president falsely claimed were the highest ratings in history. Presidents Clinton, W. Bush and Obama all eclipsed this figure during their presidential terms.

What to expect from the 2019 State of the Union

The State of the Union address is typically one of the more optimistic and bipartisan speeches a president gives. As its purpose is ostensibly to provide an update on the progress of the presidency, it makes sense for it to take this dignified tone. But this year's State of the Union has already become the most politicised in history. During the longest ever partial government shutdown Speaker Pelosi rescinded her invitation for Trump to deliver the speech to Congress, citing concerns over underfunded State and Homeland Security departments. The White House has insisted the speech will not deviate from this and will be a call for unity.

Having now agreed to give the address on February 5, Trump has become only the second president to delay a State of the Union after Reagan delayed the 1986 State of the Union in mourning of the Space Shuttle Challenger crew who perished on the day he was set to deliver it.

The power play over this address almost ensures that its tone will be markedly different to any previous iteration. The call may be for unity, but expect skepticism from both sides of the aisle, especilly if the president again thanks the workers that he says were happy to endure the shutdown for border security. Though such optimism is the norm, it is not unprecedented for an honest and dour message to be delivered. Gerald Ford told the joint session in 1975 "I’ve got bad news, and I don’t expect much, if any, applause… the state of the union is not good". It was the blunt end of a proposal for economic reform. It is hard to envision the 45th president using such a large podium free from journalists' interjections to openly admit failures, even as a means to set the agenda, or mark a new era of bipartisanship.

In his first State of the Union in 2018, Trump stuck to the teleprompter script and delivered a more or less stock-standard address. He observed a “new tide of optimism” sweeping the country and touted low unemployment figures and the strength of the economy as markers of his administration’s success. He extended “an open hand to work with members of both parties” and asked that Congress increase its spending on the military as well as infrastructure projects. He forecast a hard-line stance on North Korea and listed China and Russia as rivals.

In 2019 it will be the newly elected Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi – and not Paul Ryan – sitting over the president’s left shoulder as he speaks.

As optimistic and conciliatory a line will not land the same way. In 2019, it will be the newly appointed Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi – and not Paul Ryan – sitting over the president’s left shoulder as he speaks. Trump's relationship with Pelosi deteriorated rapidly over the course of the government shutdown as the house speaker came to represent Trump's inability to overcome the impasse over funding for his promised border wall. It is likely, then, that the speech will take the tone of a muted attack on the Democrats and the president’s perceived opponents for being unwilling to work with him.

The oft-touted achievements such as job numbers, a new US-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) trade agreement, a tough stance on China, success against the Islamic State and tax reform will be listed as having occurred despite unfair opposition, and the president’s failures listed as wins waiting in the wings presently thwarted by those same opponents. The president will likely call for an end to personal attacks on his presidency and endless opposition he faces. This kind of State of the Union address finds precedent in the Nixon era, where the beleaguered president famously declared in his 1974 address “one year of Watergate is enough”.

On the policy side of the address, it is clear that immigration will continue to be a theme of the president’s agenda. This has strengthened through the 2018 midterm elections and into the New Year. As the 2020 election draws nearer and Democrats start to shape-up for their primary contests, Trump will not miss this opportunity to campaign early and hard on a wedge issue. He is likely to give his claims to bipartisanship ballast by again reaching accross the aisle on the subject of infrastructure investment.

Who will be the designated survivor in 2019?

As all members of the legislative, executive and judicial arms of governments are expected to be present at State of the Union addresses, there are security measures in place to ensure that in the case of a calamity, the presidential line of succession is preserved. As such, a ‘designated survivor’ is nominated to cover for the unlikely event that all those attending the State of the Union die.

Explainer: What is DACA and who are the Dreamers?

This survivor is usually a member of the cabinet and is given a full presidential secret service detail and taken to a secure location offsite for the duration of the proceedings. Reportedly accompanying the designated survivor for the evening is a military aide who carries the nuclear football.

For security reasons, the identity of the designated survivor only becomes apparent very shortly before the address is set to begin. In 2018 not even Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue’s staff knew that he was nominated until the afternoon of the State of the Union and they continued to plan for his attendance and related media events.

Additionally, since 2005 both parties have absented members to potentially act as a ‘rump legislature’ in the case of calamity.