On 23 July 2025, President Donald Trump unveiled "America’s Artificial Intelligence Action Plan." This explainer unpacks the contents of the plan, the trajectory of US Artificial Intelligence (AI) policy and key considerations for Australian policymakers.

What is the AI Action Plan?

President Trump has made US leadership in AI a priority of his administration. Within days of his inauguration, Trump issued an executive order announcing the development of an AI action plan and rescinding Biden-era policies which he argued had stifled US innovation.

The joint authors of the Trump administration’s plan are David Sacks, President Trump’s AI and Crypto Czar; Michael Kratsios, Assistant to the President on Science and Technology; and Secretary of State and Acting National Security Advisor Marco Rubio. Dozens of federal agencies and over 10,000 public comments contributed to the drafting process.

The United States' AI Action Plan was launched on 23 July at a summit titled ‘Winning the AI Race’. In his speech to technology leaders, venture capitalists and MAGA faithful, President Trump declared that “America started the AI race and would do whatever it takes to win it.” At the same event, the President signed three executive orders to give immediate effect to actions on building AI data centres, exporting US AI to partners and allies and preventing ideological bias in AI models.

What is in the plan?

The AI Action Plan sets out a pro-innovation, pro-growth US agenda for AI. The plan is ambitious and comprehensive in scope, outlining over 90 initiatives across three pillars: innovation, infrastructure, and international diplomacy and security. It places the private sector firmly in the driver’s seat, positioning the US Government’s role primarily as one of deregulation, industrial support and securing the critical inputs to AI such as chips, energy, data and labour.

Pillar I: Innovation

Cutting red tape is a key focus of the Action Plan, with federal agencies given broad mandates to revise or repeal current regulations and rules that hinder AI adoption or development. Crucially, the plan empowers federal agencies to consider a state’s AI regulatory climate when making funding decisions, thereby acting as a brake on states over-regulating AI.

Crucially, the plan empowers federal agencies to consider a state’s AI regulatory climate when making funding decisions, thereby acting as a brake on states over-regulating AI.

Workforce is another priority in the plan, responding to concerns among working-class Americans that AI may lead to fewer job opportunities. The administration says it supports a “worker-first AI agenda” that aims to grow AI skills and transition workers to an AI-driven economy. In April, the Trump administration issued executive orders to improve AI education for young people. The Action Plan builds on this by committing to industry-led training programs, new education funds, apprenticeships and incentives for employers to upskill existing staff. Some of these initiatives are geared towards increasing the number of electricians, HVAC technicians and other trades required to build and maintain AI-related infrastructure. Acknowledging that AI is likely to cause labour market disruption, the Department of Labor is tasked with tracking the impact of AI on job creation, loss and wage effects, and assisting displaced workers and sectors.

The Action Plan identifies slow adoption as a bottleneck to harnessing AI’s full potential. To accelerate adoption, the government plans to create “regulatory sandboxes”. These are pilot programs where startups and researchers can rapidly deploy and test AI tools before they go to market. In some sectors like healthcare, energy and agriculture, the Action Plan promises to develop national standards with the aim of improving AI uptake in these sectors and measuring productivity gains. Government adoption of AI also receives a boost. The Action Plan proposes to launch programs that build AI skills within federal government agencies and encourage federal employees to use AI. For the Department of Defense (DoD) in particular, the Action Plan proposes to automate more of the DoD’s back-office operations, build high-security data centres to be used for military and intelligence purposes, and create a virtual environment to test the warfighting capabilities of AI and autonomous systems.

Finally, Pillar I commits to advancing scientific breakthroughs in AI through research prioritisation, investment in cloud-enabled research labs, and expanding the research community’s access to cutting-edge compute and datasets that are essential for training AI models.

Pillar II: Energy and infrastructure

Pillar II of the AI Action Plan centres on building the physical and energy infrastructure needed to support the AI boom, such as data centres, semiconductor manufacturing facilities and energy. President Trump has criticised regulatory barriers that have slowed AI-related infrastructure projects. Approvals to connect data centres to the power grid, for example, currently take an average of four years. To cut red tape, the administration has pledged to fast-track permitting processes and wholly exempt certain projects from the environmental reviews and approvals normally required under the National Environmental Policy Act. Loans, grants and tax incentives will be made available for new large-scale data centres, semiconductor facilities and related infrastructure. Federal lands will also be freed up for their construction.

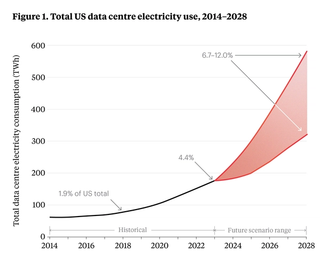

The Action Plan positions energy policy as indivisible from AI policy, due to AI’s massive energy demands. The Department of Energy projects that data centres will account for around 7-12% of the United States’ total electricity consumption by 2028, up from around 4% in 2023 (see figure 1). The Biden administration had also sought to address AI’s increased energy demand, including through reforms to permitting. However, while the Biden administration focused on transitioning to renewables, President Trump is seeking a more diverse energy mix, including natural gas, oil, geothermal, nuclear and what he calls “clean, beautiful coal” to power AI. For example, earlier in July, Trump announced US$90 billion worth of private investment in AI and energy infrastructure in Pennsylvania that combines gas, coal, nuclear and hydroelectric initiatives.

Pillar III: The United States' AI alliance

While the first two pillars of America’s AI Action Plan are domestically focused, Pillar III focuses on leveraging the United States’ technology advantages into “an enduring global alliance.” AI competition between the US and China continues to heat up, especially after the January release of China’s DeepSeek R1, a high-performing AI model that is available at a fraction of the cost of comparable American products. Rather than cede ground to China, the United States seeks to drive global adoption of US AI systems, standards and governance models.

There is a clear recognition in the AI Action Plan that if the United States does not meet global demand for its technologies, countries will turn towards Chinese alternatives. To promote international adoption of American AI, the Action Plan commits to establishing a US AI Exports Program to support “full-stack export packages” including computer chips, data, AI models and applications and cybersecurity protections. These packages gain access to federal financing tools such as direct loans, loan guarantees, equity, co-financing and technical assistance to facilitate exports to priority countries and regions.

To protect technology exports from theft or free riding, the Action Plan proposes more stringent export controls and verification measures, and tighter enforcement action, particularly for critical goods like semiconductors.

To protect technology exports from theft or free riding, the Action Plan proposes more stringent export controls and verification measures, and tighter enforcement action, particularly for critical goods like semiconductors. Allies and partners will be encouraged to adopt complementary protection measures across their AI supply chains. If encouragement fails, however, the plan states that “America should use tools such as the Foreign Direct Product Rule and secondary tariffs to achieve greater international alignment.” The Foreign Direct Product Rule allows the United States to control foreign-made products that use American technology or equipment, effectively expanding US authority over global supply chains.

One initiative that is directly aimed at China is to counter its growing influence in international standards-setting bodies. Since 2021, China has embarked on a “China Standards 2035” strategy to shape technical standards across a range of technological fields, including AI, quantum, blockchain and biotechnology. The United States' Action Plan commits to advocating for international AI governance approaches that “promote innovation, reflect American values, and counter authoritarian influence.” Just days after the launch of the United States' AI Action Plans, China launched its own Global AI Governance Action Plan in the margins of the World AI Conference in Shanghai. It is a clear sign of both China and the United States investing more heavily in AI diplomacy and offering competing visions of international AI governance.

What is not in the plan?

Two issues stand out as gaps in the AI Action Plan. The first is that the word “copyright” does not appear once. Over 40 copyright lawsuits brought against OpenAI, Anthropic, Cohere, Google and Stability AI, among others, are currently proceeding through state courts. Artists, performers and publishers have objected to the use of their intellectual property for AI training, which developers have defended as “fair use.” In copyright law, fair use allows copyrighted material to be used without explicit permission for purposes such as criticism, news reporting, teaching or research. AI developers have argued that training AI models on copyrighted material qualifies as fair use because it is a form of research that does not reproduce or plagiarise copyrighted work.

President Trump’s remarks at the launch of the Action Plan compared copyright disputes to paying to read a book — “you have gained great knowledge but it doesn’t mean you’re violating copyright laws or have to make deals with every content provider.” If the current lawsuits create a precedent forcing AI developers to pay for training on copyrighted material, the administration may want to take more action to strengthen “fair use” provisions for AI development.

Another omission from the Action Plan is clear requirements for pre-emptive AI risk mitigation. The plan does commit to safety evaluations, more rigorous tools to assess the robustness of AI systems, research to make “black box” AI systems more trustworthy and transparent, and better practices for responding to AI cybersecurity incidents. What is missing, however, is mandated action beyond guidelines, resources and voluntary information sharing. Companies like OpenAI and Anthropic have openly stated that their leading AI models demonstrate dangerous capabilities which require additional safety protocols to be put in place. Yet even for the most serious types of risk — for example, where an AI model provides meaningful instructions for building a chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapon — the Action Plan does not impose clear, enforceable obligations on developers to reduce the risks they find. This regulatory gap is likely to worsen as AI capabilities continue to grow.

The political dimension

Republicans are far from united on AI and technology policy. Veteran tech policy analyst Adam Thierer has characterised this as a growing tension between the “tech right” and the “populist right” factions of the party. In one camp, the “tech right” evangelises faster innovation and US technological dominance. In the other camp, the populist movement within MAGA is deeply suspicious of Silicon Valley, globalism and digital technologies in general.

This division has played out most noticeably in the defeat of a ten-year moratorium on state-based AI laws in July 2025. The moratorium, originally part of President Trump’s ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ (OBBB), would have prevented state and local governments from regulating AI if they wanted a share of federal funding for digital infrastructure. All but one Republican senator joined with Democrats to strip the provision out of OBBB, citing concerns on a range of issues, including online child safety, copyright infringement, consumer protections and states’ rights.’

In the wake of the moratorium’s defeat, the AI Action Plan strikes a slightly more conciliatory tone. It affirms that while the US Government should not direct funding to states with burdensome AI regulations, it should also not interfere with states’ rights to pass prudent AI laws. Critics say this is merely a moratorium by other means, but it may not be enough to deter activist states like New York, California and Michigan from continuing with their own AI bills. If a messy patchwork of AI regulation begins to emerge that unduly restricts innovation, President Trump has signalled that he would implement federal laws to supersede state ones. Sacks, his AI and Crypto Czar, has flagged that the administration may look at pre-empting state-level AI regulations “over the next year or so.” Such moves would likely bring divisions within Congress and between so-called “tech right” and “populist right” Republicans to a head.

Key takeaways for Australia

With Australia set to release a National AI Capability Plan by the end of 2025, there are many elements of the United States' AI Action Plan that Australia should consider. Australia ranks among the lowest of 47 countries on optimism about AI, with only 30% of Australians believing the benefits of AI outweigh the risks. However, 83% of Australians report being more willing to trust AI systems that adhere to international standards and responsible AI practices.

By first testing AI systems in controlled environments with light-touch regulatory oversight, Australia can facilitate a “try-first” culture for AI like the United States.

The Action Plan’s approach of creating regulatory sandboxes and designing national standards for AI systems in critical sectors could be effective mechanisms to build trust and lift AI adoption in Australia. By first testing AI systems in controlled environments with light-touch regulatory oversight, Australia can facilitate a “try-first” culture for AI like the United States. Regulatory sandboxes, for example, have already been used successfully in Australia to test new financial services and credit products before they proceed to licensing. By helpful coincidence, the United States plans to develop standards for AI adoption in healthcare, energy and agriculture — sectors that are major employers and contributors to the Australian economy. Australia could look to adopt or learn from US standards as appropriate.

Low knowledge of AI in Australia is contributing to low rates of adoption. Less than half of Australians believe they have the skills to use AI tools effectively, and only 24% report having accessed AI-related training or education compared to 39% globally (see figure 2). Australia, like the United States, should prioritise AI skill development in the workforce and training streams and roll out apprenticeships and job-readiness training for digital trades. Australia could also replicate US efforts to prioritise research investments in AI and expand access to data and computing power for researchers. With private companies now owning a dominant share of AI supercomputers, Australia’s world class researchers may find themselves locked out of the tools needed to discover the next scientific breakthrough.

Australia stands to benefit from greater export of US AI. However, the benefits may be small given that Australia is already a trusted technology ally that complies with US export controls and attracts significant investment from US technology firms. Perhaps a greater geostrategic benefit for Australia is the diffusion of US technologies — and therefore US engagement and soft power — into its region. Countries in the Indo-Pacific view AI primarily through the lens of productivity and economic development. The prospect of accessing the United States’ tech stack is positive news for a region buffeted by US tariffs and aid cuts.

Australia can play an active role in US AI diplomacy in our region. Australia should encourage the United States to give priority to the Indo-Pacific in its AI export program. Australian firms could participate in a US-led consortia for AI and data exports, particularly local data centre companies that could help meet the region’s growing demand for data storage and compute. The idea has been touted by Austrade, OpenAI and Atlassian co-founder, Scott Farquhar, as a business opportunity for Australia that capitalises on its natural resources, energy stability and geographic proximity to growing economies. Finally, Australia can provide technical assistance to countries on navigating and meeting US export controls and security requirements.

While Australia has always been a willing technology partner to the United States, some differences in technology policy cannot be easily papered over. The United States wants partner countries to “foster pro‑innovation regulatory, data, and infrastructure environments conducive to the deployment of American AI systems.” It intends to export not only its technologies but its pro-business governance models. Australia’s stronger appetite for regulating big tech may create frictions with the United States on policies such as news media bargaining (which would require global platforms to pay for Australian local news content) and social media restrictions for children under 16. Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is also unlikely to share President Trump’s enthusiasm for exempting AI-related infrastructure from environmental approvals.

While Australia has always been a willing technology partner to the United States, some differences in technology policy cannot be easily papered over.

To what extent should Australia align with the United States' AI Action Plan? The answer is a lot, but not on every policy issue. The United States has set out a clear agenda to win the AI race against China. However, the ‘race’ paradigm has always been more problematic for middle powers like Australia — countries that want to reap the benefits of AI and do not necessarily buy into an aggressive, zero-sum game played by rival superpowers. Even if Australia backs the US horse in the race, AI is a general-purpose technology that is more difficult to control and deny to others compared to the space race or nuclear race of previous generations. Australia cannot sit on the sidelines and let transformative technologies pass it by. The immediate priority for the Australian Government should be determining what success looks like for Australia beyond the debates about who is winning or losing.