Introduction

On 7 May 2025, the United States Studies Centre (USSC) convened 60 experts from diverse backgrounds for a Track 1.5 policy dialogue: Aligning security and economic interests in the age of AI. Held in Sydney with the support of Microsoft and the Australian Department of Industry, Science and Resources, this was the first of the USSC’s new Economic Security Dialogue Series.

The dialogue was held under the Chatham House Rule. This record offers a flavour of key topics and themes from the day’s discussions.

Supported by

.svg%20(1).png?rect=0,1,3400,808&w=320&h=76&auto=format)

The views expressed herein are not necessarily the views of the Commonwealth of Australia, and the Commonwealth of Australia does not accept responsibility for any information or advice contained herein.

1. AI capabilty on an

exponential path

Artificial intelligence (AI) encompasses a range of technologies that allow machines to perform tasks traditionally requiring human intelligence. AI is already embedded in the systems and services throughout everyday life — the opportunity to ‘opt out’ of the AI age has passed.

There has been a step change in AI capabilities over the past three years, allowing users to replicate expert-level proficiency in many areas. Exponential trends in capability development show no signs of plateauing, as the AI frontier moves beyond chatbots to reasoners and now to AI agents (see Table 1).

Where chatbots (e.g. OpenAI’s ChatGPT) have become very good at providing ‘on the spot’ answers, advanced reasoning models involve more problem-solving and now outperform human experts in most domains of natural science (e.g. mathematics). Agents, as the next frontier, use tools and interfaces to act autonomously on a human’s behalf.

The latest large language models are already performing a diverse range of tasks, such as supporting radiology work,1 aiding materials design,2 and undertaking protein analysis and drug discovery.3 McKinsey estimates that almost 80% of organisations are using AI in at least one business function (e.g. IT, marketing and sales or human resources).4 Emerging economies are embracing this technology ahead of high-income economies, as evidenced by measures of AI trust (57% vs 39%) and adoption (72% vs 49%).5

The proliferation and development of advanced AI systems — from the arrival of ChatGPT in October 2022 to the release of Deep Seek’s R1 model in early 2025 — offer important insights. First, algorithmic improvements are in line with expectations, but their source, by country or entity, can be unexpected. Second, while high-end computation capacity clearly matters, costs of general-purpose AI and barriers to entry continue to fall. Third, the gap between frontier labs and competitors (now roughly six months) still remains but has fallen noticeably. Fourth, users everywhere can now access multiple open-source models with advanced capabilities.

This rapidly changing AI landscape raises profound governance issues, especially given the large gap between the advanced state of the technology and the technical knowledge base (and bandwidth) of governments. The information gap between what AI companies know about their systems and what governments know highlights the importance of partnerships between public-and private-sector actors in developing durable and trusted AI policy and regulatory regimes.

The pace of future progress in general-purpose AI capabilities has major implications for managing emerging risks. Some experts view the rise of AI agents as amplifying risks in areas such as cybersecurity, weapons development (including chemical and biological weapons), and criminal misuse in all its forms. The prospect of artificial general intelligence (AGI), where cognitive tasks are performed at the same or higher level than humans, raises further questions about regulatory safeguards, the locus of responsibility/liability and the potential loss of human control. The ‘black box’ nature of AI systems — the difficulty in understanding how precisely they will behave and the difficulty of detecting dangerous behaviour — presents unique challenges for policymakers and regulators.

Policymakers across jurisdictions are striving to find the right balance where regulation can help to build trust and mitigate risk without stifling adoption or innovation. Safeguards will remain critical in limiting the ability of malign actors to access advanced systems, while ensuring those same capabilities remain available to benign users.6 In this light, the choice between safeguards and regulation, on the one hand, and opportunity and innovation, on the other, can be a false one. A degree of consensus has emerged around:

- The need for rational risk assessment with clear specification of risk variables.

- The need for AI policy frameworks to accommodate multiple objectives beyond protection from potential harms — including in domains of national security and economic security.

- The need for deeper partnerships across government, business and civil society to manage relevant risks and to unlock societal benefits.

2. Competing technology ecosystems

Strategic competition between the United States — together with allies and partners — and China — working more closely with Russia and other authoritarian powers — is a central factor in today’s geopolitical environment. A battle for technological supremacy in AI sits at the heart of this contest. It is impossible to disconnect this all-pervasive, dual-use technology from national security and economic security considerations.

Competition between US-centric and China-centric technology ecosystems extends beyond semiconductors and other AI-related hardware to the core drivers of innovation, application, adoption and diffusion. It encompasses control over data and the infrastructure used to run large AI models, advantages in cloud computing, as well as strategic dimensions of workforce, critical minerals and energy supply challenges.

The Trump administration’s AI Action Plan (released subsequent to the dialogue) outlines more than 90 initiatives focusing on deregulation, industry support, accelerating AI adoption domestically, securing critical inputs to AI and winning the AI race against China.7

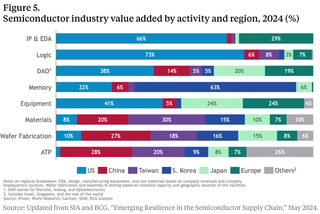

While China retains dominance in the processing and refinement of critical minerals, a key input to semiconductor manufacturing, the broader semiconductor supply chain is more contested and diverse (see Figure 1). Certain chokepoints remain tied to the United States (in intellectual property, manufacturing equipment and logic).8 South Korea retains strong presence in memory, while production of the most advanced chips is dominated by firms outside of China.9

The United States leads in the realm of advanced AI models, but the gap in number and performance is closing.10 The application layer is a major arena for competition — as companies seek footholds in markets with their AI software, locking in clients and customers as quickly as possible.

The United States leads in the realm of advanced AI models, but the gap in number and performance is closing.

The ability to adopt and integrate AI at scale is fundamental to the technology’s ‘force multiplier’ potential in terms of its capacity to improve both the efficiency and effectiveness of existing and emergent capabilities.11 With the West’s adversaries collaborating more closely in offensive cyber actions and other AI-related threat vectors, a latticework of collaboration and data sharing, including between the public and private sectors and across like-minded countries, is increasingly important.

For countries that are not technological superpowers, the ability to apply and diffuse AI is seen as more important than capability at the frontier. Conversely, being at the frontier will not be decisive if the United States and its allies fall short on adoption and diffusion. China’s strengths on scale and cost in various domains underline the need for a joined-up approach to industrial strategy across allies and partners.

For countries that are not technological superpowers, the ability to apply and diffuse AI is seen as more important than capability at the frontier.

AI is increasingly central to the defence and intelligence enterprise, raising both opportunities and risks for national security policymakers in liberal democracies. Benefits include the ability to sort through enormous amounts of data and strengthened early-warning systems using pattern recognition and decision speed. These attributes also highlight vulnerabilities and present democratic governments with dilemmas as they seek to maintain social license while not ceding ground to rivals likely to operate by different rules, norms and values.

The strategic context, though challenging, offers opportunities to Australia as a close ally of the United States. With strengths in applications, talent attraction, data centre development and as a source of democratic capital, Australia could aspire to become a ‘regional hub’ in the Indo-Pacific region linked closely to the US technology ecosystem. This will require strong government commitment, a degree of urgency and deliberate choices in the technology space given intense global competition.

3. International perspectives on the opportunity/risk equation

As they look to build and adapt AI policy frameworks, governments inevitably approach the opportunity/risk equation from different starting points. This reflects variables such as differences in technological readiness and in the way domestic values shape thinking around safety and risk vis-à-vis opportunities and societal dividends.

In the United States, both inside and outside government, the safety conversation has taken a backseat to the pursuit of capability and innovation. The Trump administration has signalled an intent to unshackle US AI firms from regulatory burdens, accelerate frontier development and promote US technology as the ‘gold standard’ in security and capability.12

China is active in the Global South, promoting its AI models and broader technology ecosystem as part of the Digital Silk Road initiative with an eye to diffusing the technology throughout new markets. The ability of countries to understand (and price in) security risks generated by technological choices looms as a key issue. Like-minded partners and allies in the Indo-Pacific need to work together to tip the scales on trust and affordability.

Japan’s AI policy framework sets out to balance innovation and security, with a strong emphasis on economic security and international collaboration. It builds on the G7 Hiroshima AI Process launched in 2023 under Japan’s G7 presidency to promote safe, secure and trustworthy AI development.13 Japan regards such international collaboration as essential to establishing trusted settings for the whole AI ecosystem — hardware, software and infrastructure — in a form that is also affordable and accessible.

South Korea’s AI strategy as outlined at the dialogue embraces infrastructure, technology, applications and institutional foundations. There is a strong focus on the ability to apply and create value from AI, rather than striving for leadership in all aspects of the technology. A primary goal is to build shared recognition among Korean citizens that AI is critical to the nation’s future. This aligns with efforts to foster cross-institutional data-sharing, protect vulnerable groups from risks and boost AI infrastructure availability.

Similarly, Singapore has adopted an all-of-society approach to building a baseline of capabilities, recognising that AI development will often outpace regulations and governance. Building consensus on risk management (especially in tackling upstream risks that cannot be addressed by late-stage safeguards) and supporting development of non-English models (e.g. SEALION) are among key areas of focus.14

AI’s dual-use nature will likely place limits on collaboration, even among like-minded partners.

Most regional governments understand their limited ability to influence cutting-edge AI developments, including the actions of the United States and China as technology superpowers. Policies are directed towards gaining advantage in specific areas — for example, incentivising diffusion or building national capability in certain niches, such as critical minerals production, semiconductor manufacturing or non-English language models.

Views on the balance between opportunity and harm will shape approaches to collaboration — including through the International Network of AI Safety (and Security) Institutes. AI’s dual-use nature will likely place limits on collaboration, even among like-minded partners. It will be important in this context to maintain regular dialogue on high-stakes AI deployment scenarios and potential national security risks.15 Private-sector actors, including leading-edge AI developers and deployers, also have a large stake in setting priorities for international collaboration.

Prime candidates for greater collaboration include: finding solutions to counter loss-of-control risks, particularly as the technology approaches AGI capability; establishing credentialed, third-party risk assessments where assessing risks across the AI supply chain is vital to pricing the ‘security externality’; and establishing mechanisms to prevent rogue-actor AI use in cybercrime.

4. Australia’s emergent AI regime: Key considerations

Australia has considerable strengths in seeking to unlock economic and societal benefits from AI. This includes political stability and the rule of law, an educated workforce, high living standards that can attract global talent, available land, a mature financial sector, strong cyber architecture and well-regulated markets. Among weaknesses that need to be addressed are siloed government decision-making (including at the state level), slow planning and approval processes, and capacity constraints in energy and specialist skills.

The Australian Government has identified AI as central to addressing the nation’s productivity challenge.16 Diffusion is perhaps the most critical variable in understanding implications for the economy and productivity. Maintaining market incentives and reducing barriers to access and innovation are important goals in this context. The urge to regulate needs to be tempered by an understanding that blunt tools are likely to have unintended consequences.

There is broad consensus that Australia should not chase every layer of the AI tech stack, though opinions vary on areas of competitive advantage and the implications for government policy. Data centre development, the datasets on which AI relies and applications in health, mining, and financial services have been identified as among the potential sources of economic opportunity for Australia. Others include forward-leaning procurement reforms that make programs inclusive of and attract new technologies and champion in parallel opportunities across space and drone innovation, cyber, biotechnology and quantum.

The Australian Government’s convening power and narrative leadership will be critical to shaping debates over issues such as labour market implications, security risks and technology choices in a more contested global environment. Government bodies will need to develop new avenues to communicate and engage with the private sector in order to surmount transparency challenges and information asymmetries.

Beyond different objectives and decision-making timeframes, the “different languages” and assumptions of the public and private sectors will need to be reconciled for public-private partnerships to succeed. This is relevant in building necessary resilience in financial, energy and telecommunications systems — all of which underpin economy-wide activities.

Legal frameworks and the way public policy is made will need to evolve. AI has implications for how we write laws, how we track laws, and how regulators apply laws. Public policy implications touch areas ranging from education policy to cybersecurity, energy market regulation to government procurement rules. AI carries the promise of assisting public policy decision-making, but without necessarily offering the right answer.

Corporates in Australia are starting from different points in terms of AI readiness, with many lacking knowledge of the relevant threats. They are looking for clear guidance to allow them to act with confidence. Deeper public-private partnerships will be essential to securing AI-related opportunities and to better aligning Australia’s security and economic interests in the future.

Education policies and institutions are at the leading edge of shaping the capacity and skills of Australian society to succeed in the age of AI. A strong focus on STEM remains a good society-wide bet, alongside fostering adaptability and ongoing learning. Within the university sector, anecdotal evidence suggests younger students tilting toward “uncritical use” in their embrace of AI, while their professors fall into the camp of “critical non-use,” avoiding AI altogether. Thought should be given to how to cultivate a new path of “critical use and active shaping” to drive an intentional shift in mindset and approach.

So far, there is little hard evidence of AI causing major disruption in labour markets. Contrary to more alarmist speculation, this lends weight to a view that, historically, fears about job losses tend to be overblown when new technologies arrive. Jobs are a way of solving problems, and problems will not disappear. Governments, nonetheless, have an important role in explaining and shaping the jobs evolution associated with AI and ensuring the right frameworks are in place for ongoing skills development.

AI is not simply a ‘new skill’ to learn or a tool to use. It offers entirely new ways to do entirely new things. It is about building dynamic capability within organisations. Much of the responsibility in this context falls to management. The large role that small business plays in the Australian economy underlines the importance of diffusion to ensure the productivity benefits are not concentrated in a few large firms.

Success in the AI economy will be governed by its capacity to generate higher incomes, not a higher stock market. It will come via Main Street, not Wall Street. Falling costs and barriers to entry point to why this is the case.

5. Trust, regulation and the social compact

Studies show an AI ‘trust deficit’ in many high-income economies, with Australia no exception.17 This sentiment can be seen in public discourse and in government statements that reflect concerns about threats to privacy, the importance of fairness and transparency, and the need to safeguard vulnerable communities from AI-related risks.18

In these circumstances, AI ‘boosters’ need to recognise that trust must be earned, not demanded. Claims regarding the benefits of AI for productivity and economic opportunity cannot be divorced from considerations of the wider social compact. By the same token, there are risks that flawed or partial evidence relating to trust could lead to unnecessary regulation.

Those concerned about regulatory overreach emphasise the need to be specific about AI-related risks; otherwise, the default can be towards a growing maze of overlapping regulation with limited clarity on how it applies to AI. Others start from a position that existing laws may not be sufficiently robust to pick up all the harms that could arise, alongside the challenges that the AI ‘black box’ phenomenon presents to the enforcement of existing laws.

There is the potential for a country like Australia to thrive and compete in a way that upholds and affirms the best of liberal democratic values.

Debate will continue over the need for new AI-specific laws and regulations versus relying mostly on existing policy and regulatory frameworks. By the same token, there is general recognition that scaled up societal defences will be necessary in areas such as law enforcement and cybersecurity.

Both public and private-sector organisations face the challenge of ensuring citizens and customers can trust those adopting and regulating AI. The onus is on governments and the business community to demonstrate to Australians how AI benefits their daily lives and empowers them in different contexts. If the right policy choices are made from a whole-of-society perspective, there is the potential for a country like Australia to thrive and compete in a way that upholds and affirms the best of liberal democratic values.