Executive summary

Industry clusters are seen as critical to economic growth and national competitiveness in the United States.1 They’re deemed so important to the United States that the Department of Commerce, the Economic Development Administration and Harvard Business School maintain more than 50 million data points mapping them.

Research from this US Cluster Mapping2 shows clusters increase the productivity and growth of existing companies, create jobs and new companies, drive innovation and support the survival and growth of small businesses.3 Clusters bring together a knowledge-based ecosystem of technology, talent, competing companies, universities and research institutes.

To the west of Sydney all these cluster components will be required if the Australian and New South Wales governments are to fulfil their vision and plan for the 1,700 hectare (4,200 acre) Badgerys Creek Aerotropolis, a self-contained business park built around and integrated into the greenfields Western Sydney Airport. Placed at the heart of the envisioned Western Parkland City that encompasses the established centres of Liverpool, Greater Penrith and Campbelltown-Macarthur,4 the Badgerys Creek Aerotropolis is a focus of development and growth for all levels of government.

The governments have set ambitious targets in the area of Western Sydney industrial policy. Early indications are that the investment required is being planned for and made. An examination of some US cluster examples and the policy settings supporting them provide additional food for thought.

Attracting the right companies to relocate or establish significant presences in the Badgerys Creek Aerotropolis will be challenging. Such industry attraction has long been a feature of US regional economic policy to the point where competition between US states is now a feature of industry development.

The New South Wales Government is looking to create a series of industry precincts focused on aerospace and defence, food and agribusiness, health, research and advanced manufacturing as part of the Badgerys Creek Aerotropolis and is inviting companies to partner with them as anchor tenants.5 US defence prime Northrop Grumman is the anchor tenant for the aerospace and defence industries precinct.6

As a greenfields area on the outskirts of the metropolitan area of Sydney, attracting the right companies to relocate or establish significant presences will be challenging. Such industry attraction has long been a feature of US regional economic policy to the point where competition between US states is now a feature of industry development.

Looking to 2026, when Western Sydney Airport is due to open, and recognising the rapid nature of technology-driven change, now is the time to focus on the technologically-advanced aspects of these target industry sectors. In the United States clusters are hubs of innovation; by attracting those companies at the leading edge of science and technology, and where proximity to an airport is an advantage, the aerotropolis will be setup to succeed. Aerospace is a natural fit. Additive manufacturing — or three-dimensional metal printing — of customised medical devices brings together health and advanced manufacturing for on-demand delivery for surgical needs. Aeroponic production of organic fruit and vegetables, a highly efficient approach of growing plants indoors without soil, could be the model for agricultural exports from Western Sydney Airport.

Attracting a world-class university, as outlined in the plans for the Badgerys Creek Aerotropolis, will be crucial. Universities are the principal ideas-sharing venues in global cities7 and are a key source of future workforce as well. Some of the most famous US clusters, such as Silicon Valley and Boston are as recognisable for their universities as they are for their industry leaders.

Clusters occur organically, reflecting the assets and competencies of a region. The onus therefore on all levels of Australian governments focused on the success of the Western Parkland City is to get the settings right on the mix of technology, talent, competing companies, universities and research institutes. This will give the already nominated precincts within the aerotropolis the best chance to develop into clusters reaping the kinds of economic benefits experienced by the regions where clusters have evolved in the United States.

Recommendations for Australia

- The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources should work towards concluding pre-clearance protocols with key export markets for future sterile horticultural exports.

Aeroponic production of organic fruit and vegetables, a highly efficient approach of growing plants indoors without soil, could be the model for agricultural exports from Western Sydney Airport. Customs pre-clearance (where goods are processed through the destination country’s customs prior to air-freighting) of high-value produce going to key export markets where freshness is prized would support Australia’s reputation for high value horticultural products. - The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration should establish guidelines of surgical implants made by additive manufacturing to enable Australia to gain a toehold in this emerging market.

Three-dimensional printing of customised surgical implants for just-in-time delivery to operating theatres around the world is a clear opportunity. With the United States the top export market for Australian medical devices and diagnostics exports,8 Australia should be looking to align with the emerging guidelines for customised surgical implants and look to play a role in setting standards for this nascent sub-industry. - Australia should set a target in national industry policy to move out of simple components and into complex subassembly work in the aerospace sector.

If Australia is to move up the aerospace supply chain from playing a sustenance and maintenance role into complex subassembly manufacture, the federal government will need to use its industry policy more aggressively in defence procurement. The state government will need to back this effort up with the attraction of US defence contractors and also higher education facilities that can provide a pipeline of skilled graduates. - All levels of government around Western Sydney need to examine the range of financial incentives on offer to secure anchor tenants.

Government leadership will be essential to attract the large-scale, long-term investment by businesses that will be required to create an aerotropolis capable of delivering globally at scale.9 For American companies, incentives are often an expected part of investment attraction, and while Australian governments appear to be approaching industry attraction on a case-by-case basis, much can be learned from examining the US experience of cluster development.

Definitions |

|

aerotropolis |

|

John D. Kasarda, one of the world’s most prominent thinkers on airport cities defines an aerotropolis as a part of a city centred on an airport, where the layout, infrastructure and economy is planned to maximise the ease of access to air transport.[^10] An aerotropolis is thus considered: a planned and coordinated multimodal freight and passenger transportation complex which provides efficient, cost-effective, sustainable, and intermodal connectivity to a defined region of economic significance centred on a major airport.[^11] |

|

cluster |

|

A cluster is described as a geographic grouping of closely related industries, where companies are connected by a shared workforce, supply chain, customers or technology. Clusters occur organically and include core businesses and industries as well as support companies. Together these form a business ecosystem beneficial to all, often reflecting the unique assets and core competencies of the geographic region.[^12] |

Introduction

“Aerotropolis” or airport cities (interconnected business parks in close proximity to a well-connected airport, characterised by highly sophisticated logistics and supply chain management) have opened up global trade in goods and ideas the way railroads and ports did before them.13

The country with the most experience of building airport cities is the United States. For more than 40 years, public policy has led city and state governments to both bolster airport development and also attract advanced manufacturing to their localities. Often there is a symbiotic relationship between air connectivity and high-paid employment: As world-leading aerotropolis expert John D. Kasarda documents, the airport of the 21st century is the seaport of the 19th, an essential part of the global supply chain. But today’s supply chain is in knowledge, so the connectivity of people and ideas is paramount. More than infrastructure plays, airports are policy levers in the United States.

US urban policy since the Second World War has been to stimulate economic growth by co-locating talented people alongside business, often through government subsidy. A classic example is around Raleigh, North Carolina, where lawmakers gave generous payroll tax exemptions and free land grants to attract IBM in the 1960s, when computer science was in its infancy. This in turn rejuvenated the state’s universities, which provide the bulk of the graduates for the now booming Research Triangle Park business park.

Western Sydney Airport, the greenfield airport site in Badgerys Creek, some 43 km (27 mi) west of Sydney’s central business district and due for completion by 2026 is envisioned as an opportunity to build an aerotropolis from scratch.14 Constructed on federal government land, the state and national governments are promoting their joint vision of a new city emerging in the area surrounding the new airport, with a well-educated population supporting advanced manufacturing jobs in aerospace, agribusiness and health.15

The goal is to create a cluster around Western Sydney Airport where talented workers graduate from universities onsite and go on to develop new products that are manufactured and exported right within the confines of the new precinct itself.

There is already A$20 billion (US$14.3 billion) in public funds on the table to develop the airport and its surrounds. Transport experts suggest that getting the road and rail links right will be the single biggest factor in the plan’s success.16 Yet there are also ambitious plans to use the hand of government to seed the new advanced industries that could co-locate within the airport perimeter itself.17 The aim is to foster those industries most likely to succeed and set the conditions for their growth. In short, the goal is to create a cluster around Western Sydney Airport where talented workers graduate from universities onsite and go on to develop new products that are manufactured and exported right within the confines of the new precinct itself.

Looking at the US experience, these kinds of clusters tend to rely on three kinds of government intervention: regulation, infrastructure and financial assistance. Of these, the Australian Government has already smoothed the path in the first case, through its assumption of project control. Meanwhile the New South Wales Government is committing time and money to building roads and rail links.18 Evidence from the United States suggests this needs to be backed up with financial inducements to ensure the right companies take the risk in relocating to any new business precinct.

In Western Sydney, aerospace, medical devices and precision agriculture have been earmarked as the sectors that both benefit from proximity to an airport for just-in-time logistics, and also where Australia has potential competitive advantage. Of these, medical technology appears to be the best fit without further government intervention, with a healthy export sector already in place. AgTech, or next generation agricultural technology, is an area where Australia could also excel. Early analysis would, however, cast doubt on the aerospace sector flourishing in Western Sydney without heavy government intervention.

Alongside government investment, higher education institutions will need to be persuaded to locate a related campus in the Western Sydney Aerotropolis. In the United States and Europe, the existence of researchers and academic topic specialists alongside business is a key attribute of successful industry clusters.

Western Sydney Airport has some excellent policy settings around it: both national and state governments have argued for 24-hour operation, boosting its chances of being Sydney’s leading freight airport within a decade. There is also ample space for the planned aerotropolis to be built with industrial zoning. The focus must now be on the industrial policy that ensures the right talent and the right employers are attracted to set up their facilities in the new airport. Evidence from the United States suggests this will require both policy levers and financial sweeteners to attract and retain the brightest and the best.

Industry clusters in the United States

Employment clusters date back almost as far as industrialisation. In 1890, British economist Alfred Marshall noted the phenomenon of agglomerations of small- and medium-sized companies in the same or related industries forming in towns and cities.19

The importance placed on the knowledge drivers of business clusters — entrepreneurship and innovation — versus the production drivers — suppliers and partners — differs between the United States and Europe.20 Industrial districts in US cities tend to follow the Marshall tradition of laissez-faire economics, with universities and publicly-funded research facilities creating the right conditions for local knowledge spillovers.

In the United States, the Marshall industrial district model explains the tendency of competing firms to colocate in a region, in order to bring about economies of scale of labour, suppliers and distribution networks.21 More recent studies by urban economist Michael Porter identify three influences on competitive advantage from clusters: an improvement in static productivity, opportunities for greater innovation in a cluster, and the emergence of new firms and business ideas that expand the cluster.22

In contrast, much post-war industrial planning in Europe followed a competing vision of clusters from French social scientist François Perroux, who hypothesised that regional ‘growth poles’ can be created by government policy by locating both the suppliers of parts and components, and also the raw materials infrastructure required to support entire manufacturing industries.23 In the Perroux model, academic institutions are less important than industrial facilities. Australia has tended to follow the United Kingdom, which in turn follows continental Europe, with regional growth poles. Yet the US model has arguably been more successful in increasing industry clusters.

Research led by Harvard Business School into US industrial clusters has shown that although clusters are more prevalent in high-income locations, they can also stimulate regional economic competitiveness by encouraging higher rates of job growth, new business formation and innovation in poorer towns.

In the United States, North Carolina Governor Luther Hodges [1954-1961] had a bold solution to halting the decline in his state’s fortunes, ranked one of the poorest states in the union in the 1950s. He designated more than 17 square kilometres of national parkland in the Piedmont region as a scientific research park.24 One of the first of its kind, the Research Triangle was bounded by the state’s three main college campuses of Duke University, North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina.

Initially looking like an expensive folly, with academics and industry sceptical of the wilderness park’s purpose, the state government successfully wooed International Business Machines (later IBM) to become a major tenant.25 The firm was attracted by a package that included free land, construction costs and a four-lane highway.26 Meanwhile, its employees and their families were given relocation grants by the state government. Many families saw this as a real hardship posting at the time, swapping prosperous New York State with an underdeveloped town on the edge of the South.27 But the funds dedicated to IBM attraction by North Carolina looks parsimonious by today’s state subsidy standards, especially when judged by the results of the experiment.

Today the Research Triangle Park (RTP) has more than 250 companies employing some 50,000 people. More than half of these have bachelors’ degrees, making it one of the most highly-educated places in the country.28 Successive state governments have bolstered the position through structural and bespoke financial incentives. The RTP has the lowest combined state and local business tax level of any region in the United States.29

What the RTP proved was that governments could plan and execute industrial clusters through a combination of financial incentive and concentration of academic institutions. Research led by Harvard Business School into US industrial clusters has shown that although clusters are more prevalent in high-income locations, they can also stimulate regional economic competitiveness by encouraging higher rates of job growth, new business formation and innovation in poorer towns.30

The triple helix of industry, academia and government

The confluence of industry, academia and government in the successful generation of cutting-edge research is often referred to as the triple helix model. Its chief proponent, Loet Leydesdorff, posits that the trinity between governments protecting intellectual property and directing research funding, universities promising campuses for research and a talent pool, and private enterprise acting as catalyst and customer, has existed since at least 1870 in Europe and North America.31

Brookings Institution, having long studied economic issues facing the United States and the world, defines this further, identifying eight essential dynamics in successful industry clusters.32

In each of the US cities studied by Brookings, there is this confluence of a highly-regarded university, strong private industry and good government policy settings. Less well understood and less frequently discussed is a fourth factor — the role of direct financial inducements by state and local governments to attract large anchor tenants of planned technology and research parks.

|

Eight success factors in industry clusters |

|

Competition between US states is a feature of industry development

In 2017 and into 2018, online retailer Amazon engaged in a very public contest to locate its second headquarters after Seattle. Some 238 city governments put in bids to host HQ2, which was then whittled down to 20 candidate cities before Arlington, Virginia was selected. The Virginian state government committed some US$750 million in economic development subsidies, grants and tax concessions to attract the company.33 During the process, Amazon was explicit in what it expected state governments to do: the firm used the word “incentive” 21 times in its request for proposals.34

Incentives are usually tax credits or workforce grants and form a central plank of most states’ economic development programs.35 Between 1980 and 2013, state and local governments in the United States awarded corporations more than US$64 billion in subsidies.36 Table 1 sets out the US subsidies received by the top 80 companies. There are now a multitude of programs, grants, loan guarantees, aid assistance, tax breaks and concessions offered by every level of government in the United States, designed to encourage investment and the creation or retention of jobs. The most common forms of assistance include state subsidies; federal grants and tax credits; and federal loans, loan guarantees and bailout assistance.37

Table 1: Top 80 companies receiving US subsidies (federal, state and local awards combined)

|

Rank |

Parent company |

Subsidy value ($US) |

Number of awards |

|

1 |

Boeing |

$14,499m |

1,422 |

|

2 |

General Motors |

$6,119m |

696 |

|

3 |

Intel |

$5,986m |

140 |

|

4 |

Alcoa |

$5,788m |

161 |

|

5 |

Foxconn Technology Group |

$4,826m |

71 |

|

6 |

Ford Motor |

$4,065m |

568 |

|

7 |

NRG Energy |

$3,537m |

266 |

|

8 |

Sempra Energy |

$3,362m |

39 |

|

9 |

Cheniere Energy |

$3,293m |

22 |

|

10 |

NextEra Energy |

$2,396m |

55 |

|

11 |

Iberdrola |

$2,288m |

105 |

|

12 |

DowDuPont |

$2,258m |

900 |

|

13 |

Tesla Motors |

$2,229m |

112 |

|

14 |

Fiat Chrysler Automobiles |

$2,199m |

215 |

|

15 |

Nike |

$2,095m |

96 |

|

16 |

Southern Company |

$1,986m |

92 |

|

17 |

Summit Power |

$1,980m |

8 |

|

18 |

General Electric |

$1,898m |

1,855 |

|

19 |

Venture Global LNG |

$1,870m |

2 |

|

20 |

Mubadala Technology |

$1,868m |

22 |

|

21 |

Sasol |

$1,848m |

67 |

|

22 |

Nissan |

$1,826m |

76 |

|

23 |

Cerner |

$1,823m |

35 |

|

24 |

Royal Dutch Shell |

$1,740m |

114 |

|

25 |

Berkshire Hathaway |

$1,681m |

700 |

|

26 |

Lockheed Martin |

$1,643m |

908 |

|

27 |

IBM Corp. |

$1,632m |

460 |

|

28 |

SCS Energy |

$1,591m |

9 |

|

29 |

JPMorgan Chase |

$1,578m |

1,070 |

|

30 |

Amazon.com |

$1,520m |

165 |

|

31 |

Energy Transfer |

$1,414m |

65 |

|

32 |

General Atomics |

$1,251m |

303 |

|

33 |

ArcelorMittal |

$1,250m |

77 |

|

34 |

Northrup Grumman |

$1,245m |

442 |

|

35 |

Duke Energy |

$1,241m |

57 |

|

36 |

Continental AG |

$1,234m |

86 |

|

37 |

Jefferies Financial Group |

$1,123m |

32 |

|

38 |

Abengoa |

$1,083m |

61 |

|

39 |

Volkswagen |

$1,071m |

65 |

|

40 |

Toyota |

$998m |

148 |

|

41 |

United Technologies |

$989m |

959 |

|

42 |

Forest City Enterprises |

$984m |

79 |

|

43 |

Exxon Mobil |

$952m |

125 |

|

44 |

Exelon |

$931m |

80 |

|

45 |

Mazda Toyota Manufacturing |

$900m |

1 |

|

46 |

Delta Air Lines |

$878m |

22 |

|

47 |

Pyramid Companies |

$875m |

67 |

|

48 |

Walt Disney |

$859m |

81 |

|

49 |

Air Products & Chemicals |

$857m |

241 |

|

50 |

SunEdison |

$800m |

112 |

|

51 |

Valero Energy |

$798m |

148 |

|

52 |

Goldman Sachs |

$797m |

246 |

|

53 |

E.ON |

$790m |

31 |

|

54 |

Texas Instruments |

$785m |

55 |

|

55 |

Alphabet Inc. |

$766m |

43 |

|

56 |

Nucor |

$760m |

115 |

|

57 |

Triple Five Worldwide |

$748m |

4 |

|

58 |

AES Corp. |

$737m |

73 |

|

59 |

EDP-Energias de Portugal |

$734m |

13 |

|

60 |

Johnson Controls |

$728m |

150 |

|

61 |

Daimler |

$710m |

135 |

|

62 |

Apple Inc. |

$693m |

17 |

|

63 |

Bank of America |

$689m |

881 |

|

64 |

LG |

$687m |

37 |

|

65 |

Verizon Communications |

$664m |

247 |

|

66 |

Bayer |

$664m |

185 |

|

67 |

Sagamore Development |

$660m |

1 |

|

68 |

Caithness Energy |

$652m |

22 |

|

69 |

Dominion Energy |

$639m |

55 |

|

70 |

American Electric Power |

$629m |

62 |

|

71 |

Ameren |

$618m |

11 |

|

72 |

Bedrock Detroit |

$618m |

1 |

|

73 |

General Dynamics |

$617m |

319 |

|

74 |

Archer Daniels Midland |

$608m |

1,069 |

|

75 |

FedEx |

$588m |

421 |

|

76 |

Mayo Clinic |

$585m |

1 |

|

77 |

Wells Fargo |

$580m |

400 |

|

78 |

Sears |

$572m |

77 |

|

79 |

Invenergy |

$571m |

19 |

|

80 |

Michelin |

$566m |

75 |

In a highly-mobile country like the United States, companies move their manufacturing bases more readily than in other developed countries.38 As a result, there is a market for luring corporate headquarters and manufacturing facilities away from one city and to another. The die was cast in 1976 when Pennsylvania crafted a US$100 million assistance package to convince German automotive giant Volkswagen to build the first foreign car manufacturing facility in the United States in Westmoreland County, 56 km (35 mi) south of Pittsburgh.39 Other European and then Japanese car makers sought — and received — similar sweeteners from rival states keen to emulate Pennsylvania’s reverse from economic decline. US automotive producers received generous packages too, which in turn spilled over to other large manufacturing businesses being able to guarantee jobs in sensitive congressional districts..

By the 2000s, some 14 large companies moved their operations across state lines after receiving large-scale government subsidy packages, with a further 11 companies paid for relocations to different cities within the same state.40 Today, corporate headquarters tend to ebb and flow between the metropolitan centres, while manufacturing is pointed towards distressed neighbourhoods and others deemed ‘opportunity zones’ by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, opening up certain investments to have tax advantages.41

Some relocation deals are more controversial than others. In 2010, for example, the video games company 38 Studios received US$75 million to move to Rhode Island from Massachusetts — where the bulk of its employees were development graduates from the Boston area universities. The state government bet on the company’s ability to attract the brightest and the best technology talent to Providence. The gamble failed when 38 Studios went bankrupt and the tiny state is estimated to have lost US$38 million on the deal.42

Equally common as relocation deals, however, are retention deals made to keep large corporations (and thus large employers) in a state or city. Some 17 retention deals larger than US$1 million have taken place over the past 30 years.43 Most of these were struck after the company threatened or hinted it would move its base if no subsidy were awarded. A recent example of this practice is the Nike athletic clothing company, which secured tax breaks worth an estimated US$2 billion over the next 30 years from the state of Oregon after it courted rival states’ relocation offers.44 However, while Nike was a high profile example of retention policies, media and financial services companies including NBCUniversal, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo have all successfully played up offers to relocate out of New York City to secure multimillion dollar tax breaks from the New York State Government.

A further string to the state government corporate attraction activity is tax rate reductions. Looking at North Carolina’s Research Triangle as an example, the state government has had to bolster its already strong position through generous financial inducements to private corporations considering the state. At a flat 3 per cent, North Carolina has the lowest corporate income tax rate in the United States (of the states that still levy the tax), however, this is set to drop to 2.5 per cent this year.45 There is also no property tax in the state. Despite lower tax receipts, the state government claims it gets good return on investment in terms of job creation in high-yield industries.46

Opportunities for Australia: Western Sydney high-tech export industries clusters

Australia can draw many lessons from the development of export industries located close to well-networked airports in the United States. Airport business parks exist across Australia, with some purpose built, such as Canberra Airport (CBR)’s Brindabella Business Park or the extensive facilities around Brisbane Airport (BNE). However, as a greenfield site at Badgerys Creek in Sydney’s western suburbs, Western Sydney Airport has prompted plans for an aerotropolis in the mould of successful US airport cities.47

In efforts to emulate US and international airport cities, part of the planned development to the south of the airport is the Western Economic Corridor. Planners hope to attract defence and aerospace activities as well as other advanced manufacturing, health, education and lifescience industries. As set out in Table 2, these industries are identified in the United States as high-technology industries, in which science and engineering occupations (scientists, engineers, engineering technicians, and science and engineering managers combined) account for at least two times their economy-wide percentage of employment.

Table 2: US high-technology industries

|

High-technology category |

Industry |

Per cent of industry employment in science and engineering occupations |

|

Very high technology* |

Computer and electronic product manufacturing |

37.4 |

|

Pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing |

32.2 |

|

|

Aerospace product and parts manufacturing |

31.0 |

|

|

Moderately high technology^ |

Petroleum and coal products manufacturing |

14.5 |

|

Chemical manufacturing other than pharmaceuticals and medicines |

12.8 |

|

|

Transportation equipment manufacturing other than motor vehicles and parts and aerospace |

12.7 |

|

|

Machinery manufacturing |

12.5 |

|

|

Electrical equipment, appliance and component manufacturing |

12.3 |

There is already some jockeying for position between local government areas as to where each industry best fits. Liverpool City Council has identified logistics and distribution, food manufacturing and defence aerospace as its target industries to attract.48 Meanwhile, neighbouring Campbelltown is pointing to the medical research facilities at Western Sydney University and the Macarthur Clinical School as draw cards for medical technology firms.49

The first two business parks within the airport perimeter have been designated as the Aerotropolis Core, which is expected to house agriculture and agribusiness, and the Northern Gateway precinct which will be rezoned to accommodate what airport planners expect to be advanced manufacturing.50

Attracting a world-class university, as outlined in the plans, will be crucial. Universities are the principal ideas-sharing venues in global cities.51 Indeed, cities rather than countries are developing stronger roles as talent hubs.52 Scientists, universities and researchers particularly rely on the cross pollination of ideas and fertilisation of concepts that take place in colocation in major cities.

There is clear evidence that universities and research institutions provide significant impetus to industry clusters’ growth. Higher education provides research and development possibilities unavailable in many other settings. It also provides a pipeline of highly-skilled human capital, which is essential in high technology and high value added industries.53 For example, Los Angeles County is a life sciences cluster thanks to research universities such as Stanford producing thousands of bioscience graduates each year.54

The Western Sydney Aerotropolis Site Plan has several hectares set aside for higher education institutions, among which is a planned aerospace campus. The key will be to persuade existing universities, centred mostly in eastern Sydney, to relocate parts of their campuses.

Today the best-known cluster for high technology and innovation is Santa Clara Valley near San Francisco, better known by its nickname Silicon Valley. Along with access to venture capital funding for entrepreneurs, access to highly-skilled workers from the University of California at Berkeley and Stanford (with its positive disposition to enter commercial partnerships) was crucial in both its formation and ongoing success.55

The Western Sydney Aerotropolis Site Plan has several hectares set aside for higher education institutions, among which is a planned aerospace campus. The key will be to persuade existing universities, centred mostly (although not exclusively) in eastern Sydney, to relocate parts of their campuses. Aerospace makes sense, due to the benefits that space could provide, but agricultural faculties from Sydney’s major universities are already devolved to regional campuses56 and it could also make sense to relocate aerospace manufacturing to purpose-built, spacious sites on the new airport site. Likewise, medical biotechnology schools could establish satellite campuses in Western Parkland City.

Western Sydney in particular has a high degree of multiculturalism that will benefit the recruitment of academic staff, with 75 per cent of the population having at least one parent born outside of Australia. Evidence from around the world has shown that cities with the highest concentrations of talent from different backgrounds are those that go on to produce the most novel inventions.57 This is where humans will still have the edge over machine learning, in the fields of cognisance and intuition.

Aerospace

The aerospace industry is one of the largest high-technology employers in advanced countries, with more than 1.9 million people employed in the industry in 2017.58 A significant share of the world’s aerospace jobs are concentrated in or around one of four aerospace clusters: Seattle (home to the Boeing Commercial Aircraft final assembly line), Toulouse (home to the Airbus final assembly line), Montreal (home to Aéronautique Bombardier) and the São Paulo-São José dos Campos corridor (home to Brazil’s Embraer). Table 3 shows the top 10 aerospace and defence clusters by employment in the United States. Advanced supply chains featuring hundreds of firms as contractors and sub-contractors work to produce the specialised sub assemblies that make up aircraft manufacturing.

Table 3: Top 10 aerospace and defence clusters in the United States by total employment

|

Economic area |

Employment |

|

Seattle, WA |

74,950 |

|

Los Angeles, CA |

50,733 |

|

Dallas, TX |

44,374 |

|

Wichita, KS |

34,959 |

|

Hartford, CT |

20,765 |

|

Boston, MA |

19,448 |

|

St Louis, MO |

19,021 |

|

New York, NY |

18,916 |

|

Washington, DC |

17,262 |

|

Phoenix, AZ |

15,223 |

For this reason, many countries have actively promoted growth in the aerospace sector. However, Australia has slipped well behind comparable countries in its aerospace industry. Not one of the world’s top 100 aerospace companies is Australian, despite firms from smaller countries such as Sweden, Israel, Denmark and Portugal all featuring in the rankings.59 Canada, considered in many ways analogous to Australia, is home to some 7.5 per cent of global aerospace jobs, most concentrated in the province of Québec.60

Furthermore, Australia’s companies are small. There are no tier 1 aerospace companies (the prime manufacturers of either fuselage or engines), no tier 2 (manufacturers of major subassemblies) and no tier 3 (system integrators). Instead, Australian aerospace companies are machine shops, parts manufacturers and raw material suppliers (tiers 4, 5 and 6 respectively).61 This is lower down the value chain than other advanced economies.

The Australian and New South Wales governments have a plan to reverse this poor global standing. The sector has been earmarked as the main export manufacturing industry expected to power the future Western Sydney Airport. The state government’s defence industry strategy outlines several objectives, including working with small businesses to gain greater access to the global supply chain.62

Many point to the success of the Dulles Corridor of defence-related aerospace companies concentrated around Washington’s Dulles International Airport (IAD) in northern Virginia. This is wide of the mark, however, as Dulles has many significant differences from Western Sydney. Firstly, the proximity to national lawmakers in Washington, DC: Dulles sits at one end of a freeway that leads to the Pentagon. In Australia, the Department of Defence is in Canberra, not Sydney.

The aerospace sector has been earmarked as the main export manufacturing industry expected to power the future Western Sydney Airport. The state government’s defence industry strategy outlines several objectives, including working with small businesses to gain greater access to the global supply chain.

Secondly, US defence contractors are industry primes. In Australia, the aerospace industry is at the level of subcontractors-to-subcontractors. Australia’s relative lack of aerospace companies is to the detriment of potential contracts. For example, British aerospace company BAE Systems, as sole tier 1 partner on the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program, has contracts worth around £1 billion (A$1.9 billion), which it is able to subcontract down to some 500 aerospace companies in its supply chain. BAE makes around 15 per cent of the JSFs and is the only supplier permitted under the US security and technology transfer agreement to retain its design rights.63

Although Australia is a level 3 partner at a country level on the F-35 program, alongside Canada, Denmark, Norway and Turkey, the titanium vertical tail sections made at BAE’s facilities at RAAF Base Edinburgh in South Australia are not part of the global supply chain.64 Instead, these parts are made specifically for the conventional take-off and landing variant of the F-35 ordered by the Royal Australian Air Force. This kind of implied quid pro quo workshare for military aircraft orders is enshrined in the industry participation policy of the Australian government.65

Many other mid-tier countries have much more explicit policies linking defence contracts with local manufacturing. The process of offset agreements differs from country to country, but a nation like South Africa, whose aerospace industry was well advanced and self-sufficient during the apartheid era, uses offset today to ensure contracts are awarded to its firms.66 The policy is a key plank of the country’s economic development, black empowerment and job creation activities.67

By contrast, most aerospace jobs in Australia are either in maintenance or sustainment. Worse still, for a large proportion of aircraft engineers in Australia, paper-based certification work has replaced the hands-on work of the 20th century. This is partly due to aircraft manufacturers guarding their intellectual property more closely, allowing peripheral outstations, such as those in Australia, only limited access to design files.68 The Australian industry remains concentrated in niche areas, including component manufacture, composites, unmanned air vehicles, hypersonics and air traffic management equipment, rather than participating on large-scale international projects.69

Australia has traditionally shied away from mandated workshare as part of its defence procurement.70 However, the new expectation is that international industry awarded defence will invest in Australian facilities and employees. As an example, the commissioning of 12 new short-fin barracuda block 1A submarines, to be built in Adelaide by a consortium led by French shipbuilder DCNS, is expected to be worth around A$50 billion in procurement, a further A$50 billion in sustainment activities, and pledges to create 2,800 jobs.71

Australia has mandated workshare for Australian companies under some aerospace contracts, notably the 2006 Eurocopter NH-90 attack helicopter purchase, which led to 42 of the 46 procured being built in Brisbane (and re-designated MRH-90 Taipan).72 As a result, southeast Queensland has the highest concentration of qualified defence aerospace engineers in the country. Boeing has a large presence in the region and the recently announced the Boeing Airpower Teaming System “Loyal Wingman” unmanned aircraft is to be developed there, with first flight as early as next year. Significantly, this is the first combat aircraft designed in Australia since the 1950s.73

To build on this, the national, state and eight local governments of Western Sydney have committed to the construction of an Aerospace Institute as part of the Western Sydney City Deal. The institute, located on Australian government-owned land close to the new airport, will be a new science, technology, engineering and mathematics facility with a focus on aerospace from high school through to tertiary education.74 US prime Northrup Grumman will become the anchor tenant of a new industry park to be built adjacent to the institute. Additionally, the state of Victoria is readying plans to expand the Fishermans Bend aerospace campus currently home to Boeing, increasing the potential skills pool in Australia.

Thus, in seeking to plant the aerospace industry into Western Sydney, the governments’ intentions are good. But with well-developed pockets of aerospace and defence expertise distributed throughout Australia, from Adelaide to Brisbane and Melbourne, it will be a hard task to emulate large aerospace clusters like those that exist around the prime manufacturers in Europe, North America or Brazil.

Food, agribusiness and AgTech

Australia should be well placed to serve the growing consumption of high-quality food imports in Asia. The growth of middle-class consumers in Asia is expected to grow from 525 million in 2009 to around 3.3 billion by 2030.75 Much of Asia, especially China, views Australian food as a high-quality product and exports of ambient products such as infant formula or health foods have already seen high growth.76 China is already Australia’s leading export market for agriculture (Table 4).

Table 4: Australia’s major agriculture export markets (2015)

|

Agriculture export market |

A$m |

Share of total (%) |

|

China |

8,906 |

19.9 |

|

Japan |

4,500 |

10.1 |

|

United States |

3,893 |

8.7 |

|

Republic of Korea |

3,410 |

7.6 |

|

Indonesia |

3,312 |

7.4 |

|

India |

1,881 |

4.2 |

|

New Zealand |

1,537 |

3.4 |

|

Vietnam |

1,504 |

3.4 |

|

Hong Kong (SAR of China) |

1,283 |

2.9 |

|

Singapore |

1,190 |

2.7 |

But Australia does not export as much high-value fresh produce as it could. Fruit and vegetables make up 19 per cent of Australian agricultural production, but Australia’s exports constitute only 1.2 per cent of global fruit exports and 0.3 per cent of global vegetable exports.77 This is largely a cultural legacy of a focus on meat and grain export, which account for 25 and 11 per cent of Australian agricultural exports respectively (Table 5).78

Table 5: Top 10 agricultural exports of Australia (2015)

|

Product |

A$m |

Share of total (%) |

|

Beef |

7,401 |

16.6 |

|

Wheat |

4,853 |

10.9 |

|

Meat (excluding beef) |

3,575 |

8.0 |

|

Wool |

3,021 |

6.8 |

|

Alcoholic beverages |

2,587 |

5.8 |

|

Sugars, molasses and honey |

2,332 |

5.2 |

|

Vegetables |

2,260 |

5.1 |

|

Dairy |

2,216 |

5.0 |

|

Live animals (excluding seafood) |

1,875 |

4.2 |

|

Fruit and nuts |

1,762 |

3.9 |

In the studies of functional aerotropolises, facilities for processing time-sensitive goods for export are often considered key. On-airport facilities, combined with road infrastructure linking the airport with agricultural land nearby should allow for advanced food production within the confines of an airport city, rather than a secondary location.79

Western Sydney Airport will have a competitive advantage over Sydney Airport when it comes to fresh food export. Due to its night-time flight restrictions, Sydney Airport is unable to accommodate the early morning freight flights required to get fresh food to export markets.80

There is huge demand in Asia for Australian produce, particularly if it is organic.81 Australian fruit exports to China grew fivefold in the four years to 2018, much of it organic, premium produce.82 In these high-value horticultural export markets freshness is prized. Every hour picked fruit and vegetable spends out of refrigerated conditions, can reduce shelf life by two days.83 So access to a climate controlled supply chain and close proximity to an airport will be crucial to any export plan for Western Sydney Airport.

Australia possesses the talent pool to grow AgTech. There are now some 300 Agri-food tech companies operating in Australia, with many support companies. Australia is also home to five of the top 50 global agriculture universities.84

On-airport facilities, combined with road infrastructure linking the airport with agricultural land nearby should allow for advanced food production within the confines of an airport city, rather than a secondary location.

The soil quality around Badgerys Creek is relatively poor and present farmers often struggle to keep up with domestic demand, let alone exports.85 But the NSW Farmers Association has ambitious plans to pioneer precision, sensor-driven agriculture at Western Sydney Airport. The body wants indoor farming in aeroponic hothouses growing high-value crops within the airport footprint for international export.86

The Fresh Food Precinct outlined by the farmers encompasses high-technology aeroponic hot houses connected to packing and labelling facilities. Only perfectly ripe fruit and vegetable would be picked, thanks to thousands of sensors in the soils. The aim is to have meal packs delivered within 36 hours of order to Asian consumers.87 One US example of the vertical farm is Plenty, whose innovative method of indoor farming attracted US$200 million in Series B venture capital investment led by Japan’s SoftBank Vision Fund.88

If the facilities can be closed, with sterile soil and air, there is an opportunity to go beyond organic and eliminate not only pesticides, but airborne pollution as well. This in turn could open the way to more extensive pre-clearance of crops, avoiding the need for customs checks in the receiving country.

Australian fruit and vegetable exporters already face some of the strictest export security checks in the world before their produce can be loaded into freight holds leaving Australia.89 This is compounded by the need for customs and phytosanitary inspections in the export market. Although some claim quarantine inspections can be used as a de facto protectionist measure,90 delays are just as often due to differences in national laws.

To combat this, New Zealand primary producers have embarked on an ambitious plan to pre-clear exports of fruit including apples, stone-fruit, tomatoes and pears prior to export to key export markets.91 There are trials too, of Australian citrus being inspected and possibly irradiated prior to export to South Korea.92

Western Sydney Airport presents an opportunity for Australia to accelerate its focus on digital agriculture. Although more than A$30 million has been delivered to digital agriculture start-ups between 2013-17 from a range of federal and state government sources,93 much of this has been directed to increasing productivity from existing paddocks using global positioning satellites, soil sensors and yield monitors to deliver “more from less”. In contrast, neighbouring New Zealand is ahead of both Australia and the United States in the maturity of its AgTech sector.94

In addition to high-value horticulture, premium red meat is another sector earmarked for export from the new airport. The Australian red meat industry is heavily export-focused95 and beef producers in the Darling Downs area of south-east Queensland are trialling same-day export of premium meat using purpose-built climate controlled facilities at the privately-built Toowoomba-Wellcamp Airport.96 An example of the potential can be found in Cairns, where some 384 tonnes (423 US tons) of live seafood is exported to Hong Kong each year.97

The main target market for Australian red meat is likely to be the Middle East. As live animal exports look to be phased out, there is an opportunity to export freshly slaughtered meat cuts. With significant competition in the airline industry between the United Arab Emirates and Australia, it is likely that a long haul service linking either Abu Dhabi or Dubai and Western Sydney Airport will be present from the earliest days of the new airport.98 Given initial passenger figures will likely be low and increase over time, high value and bulky air freight will be prized by the incoming airlines. Wet meat export can play an important role in filling the belly holds of wide body aircraft.

Medical device manufacture and export

Unlike many other high-value manufactured goods, medical devices are very price elastic. In this regard, Australia — where the minimum wage is roughly 75 per cent higher than in most US states — should still be able to find niches to export even if the cost of doing business is relatively high.

Australia’s medical devices industry comprises more than 500 companies generating total revenue of A$11.8 billion, exporting more than A$2.1 billion each year and producing almost 87,000 surgical products and medical devices.99 Medical devices require a secure supply chain and are not well suited to countries with lower standards of intellectual protection. Australia, like the United States, has a robust regulatory regime and can often fast-track clinical trials.100

Additionally, although Australia has a poor reputation for commercialising its research overall,101 in the field of medical device patents filed, Australia ranks 13th. Pioneering Australian medical inventions include the ultrasound scanner, the artificial heart valve, multifocal contact lens, the CPAP sleep apnoea machine and the Cochlear bionic ear implant.102

One known advantage of advanced manufacturing clusters is the knowledge transfer to other industries. A broad hope of the governments involved in planning the Western Sydney Aerotropolis is that investment in aerospace manufacturing will spur other sectors to co-locate in the business park keen to tap into both the expertise and personnel. In the field of additive manufacturing, there is evidence that knowledge transfer is already starting to take place between the aerospace and medical device sector.103

Additive manufacturing — or three dimensional printing of metal parts — uses metal powders of superalloys like titanium and cobalt-chrome smelted at extremely high temperatures by an electron gun operating in a vacuum chamber. US engine maker GE Aerospace has been deploying additive manufacturing to fashion turbine blades for its jet engines for more than a decade.104 The metal printing process is particularly well-suited to the production of one-of-kind sterile implants.105 GE Healthcare, a sister division, is using similar techniques for 3D-printed medical implants.

Unlike aero engine parts, where mass uniformity is the prize, many implants are not only single use, but customised to the patient recipient and produced directly from digital designs without the need for tooling or mould making, resulting in the rapid delivery of customised 3D-printed implants. Since 2014, Anatomics, a Melbourne-based bespoke surgical implant manufacturer has consistently led the field in the successful design and implementation of custom-printed titanium bone replacements.106

Of all the medical technology innovation taking place in Australia, the subsection best suited to location within an aerotropolis is the microfabrication area that includes additive manufacturing, direct writing and the rapid production of microelectromechanical systems.

Of all the medical technology innovation taking place in Australia, the subsection best suited to location within an aerotropolis is the microfabrication area that includes additive manufacturing, direct writing and the rapid production of microelectromechanical systems.107 Before 3D-printed implants, medical device manufacturing was cumbersome and labour-intensive. But additive manufacturing gives Australian companies an opportunity to develop on-demand surgical implant factories located within easy range of an international airport.108

It is estimated the additive manufacturing industry will reach US$21 billion by 2020.109 Barriers exist, however, in the widespread adoption of 3D printing of metallic parts: the raw materials required are often slightly different alloys to those used in conventional manufacturing, and the process is still slow.110

To ensure Australia retains its place at the forefront of innovation in additive manufacturing, the federal government will need to ensure the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration follows the US Food and Drug Administration in publishing guidelines to additive manufacturers in the medical device sector. The guidelines cover the 3D printing machines themselves, as well as raw material controls, post-processing of the part and revalidation of finalised parts.111 Although non-binding, the USFDA guidelines are a world first in this burgeoning industry. Australia can be in the vanguard of defining global standards and regulations for both the proprietary assets involved and the safety of the manufactured parts. In doing so, it can capture a large slice of a future industry and locate it in the heart of the new aerotropolis.

Persistent innovation policy challenges may impact aerotropolis success

In the study of aerotropolises, experts tend to agree that a focus on either high-value products for air freight or high-value people flying for business is the way to ensure the sustainability of an airport city ecosystem. These rely on access to road and rail infrastructure for the former and a highly-skilled labour pool for the latter.112 To what extent the transport infrastructure projects planned for Western Sydney Airport transpire is budgetary. However, state and federal governments agree on their priority.

The initial plans for the Western Parkland City appear to be following the advice of industry cluster experts by defining a set of priority industries and planning for an aerospace institute connected to a university, a vocational college and selective high school to ensure a pipeline of educated workers and research partnerships.113 The New South Wales Government is predicting 200,000 new jobs will be created over two decades in the region. Only 13,000 of these will be directly related to air transport.114

To develop a highly-skilled workforce, Western Sydney must be able to attract and retain top global talent. Although Australia is ranked the seventh most attractive place to work among highly-educated global professionals, its attractiveness is principally driven by lifestyle and leisure pursuits rather than professional challenge.115 Indeed, international scientific collaboration is in decline among Australian universities. In 1998, Australia and Japan were the only two Asia-Pacific countries in the main international academic papers co-authorship networks.116 Today, researchers from institutions in South Korea, Taiwan, India and Singapore are all highly active in the academic paper authorship networks, reducing the share of research collaboration being undertaken by Australian universities.117

Although Australia’s research system is strong it is not very efficient at translating research or innovation inputs into commercial outcomes and yet this will be critical in the development of successful industry clusters.

Specific policy recommendations in relation to target industries of aerospace, AgTech and medical device additive manufacturing as set out in this paper will require New South Wales and Commonwealth governments and government agencies to work together. And while there is evidence of this inter-government collaboration in the Badgerys Creek Aerotropolis planning and promotion, challenges are persistent in collaboration between Australian industry and researchers for innovation.118 This is one area where the United States does much better than Australia — a key characteristic of US clusters is the persistent interaction between industry, research organisations and educational institutions.

A major challenge is that although Australia’s research system is strong it is not very efficient at translating research or innovation inputs into commercial outcomes119 and yet this will be critical in the development of successful industry clusters.

Additionally Australia lags other OECD nations in terms of investment in research and development, at 1.94 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) — less than half that of the leading countries120 — and well below the United States at 2.74 per cent of GDP expended on research and development.121 The difference between Australia and the United States is driven by much lower business expenditure on R&D.122 The innovation benefits resulting from the links between business research and development, commercialisation and start-ups has led to recommendations to create incentives for multinational corporations to establish major R&D operations in Australia.123

Increasing collaboration between industry and researchers, increasing business investment in research and development and reversing this lack of innovation commercialisation will take effort. However, given successful industry clusters are characterised by the concentration of research organisations, educational institutions and related industries working together to drive economic benefit through jobs and wage growth; the success of industry, governments and universities in solving these challenges will define the success of the Badgerys Creek Aerotropolis.

Case study 1 | Business jet cluster: Wichita, Kansas

After failing to excite European investors with his plan to refashion a Swiss Air Force jet fighter into a private aircraft,124 US inventor Bill Lear brought his idea back to the United States,125 and Kansas in particular. At that time, the unassuming Midwest town of Wichita held the title of Air Capital of the World. The entrepreneurs who preceded Bill Lear, Walter Beech (founder of Beech Aircraft), Clyde Cessna (founder of Cessna Aircraft) and Lloyd Stearman (founder of Stearman Aircraft)126 had built an aerospace industry from scratch.

This was a combination of geography and local city planning. The city made famous by singer-songwriter Glen Campbell for its long straight roads to nowhere,127 exploited its flat terrain to establish a world-class airfield long before anyone had really thought of aerospace as an industry. The city government attracted the first federal government-supported airshow and convention, the National Air Congress, to the city in 1924, at the dawn of civil aviation, attracting more than 100,000 delegates and visitors.128 Spurred on, the City of Wichita and the Chamber of Commerce bet that the city’s central location in the United States, together with favourable weather would make a perfect place to site an airfield.129 When it opened in 1929, the city’s first municipal airport (present day McConnell Air Force Base, IAB) was a state-of-the-art facility with expansive runways.

But then specialisation occurred. Both Cessna and Beech specialise in general aviation (or private aircraft to the layman). So when Bill Lear wanted to commercialise the first mass-produced private jet aircraft, the concentration of general aviation talent in Wichita made it an obvious choice. The eponymous Learjet 23 that launched in 1963 was an eight-seater jet that could fly at 1,000 kilometres per hour at an altitude of 41,000 feet (12,500 metres). By contrast, the most popular private aircraft at that time, the Cessna 172, had a cruise speed of only 226 kilometres per hour.

The Learjet was revolutionary at the time, and derided by most of the industry as a folly. Yet the city of Wichita celebrated Lear’s maverick ways and provided the state’s first industrial revenue bond, valued at US$1.2 million, to help him commercialise the product. It was an investment that paid off: Learjet went on to not only become synonymous with private jets, but lead the market. By 2015, over one-third of all private jets sold that year were manufactured by Canadian aircraft manufacturer Bombardier, which has owned Learjet since 1990.130

Today, business jets are a lucrative niche of the aerospace industry. Some 22,000 private aircraft have been sold and 55 per cent of the US-manufactured ones were made in whole or in part in Wichita.131 Some 35,000 people work in aerospace in the city, from a population of just 600,000, making it the most highly specialised aerospace cluster in the United States.132

Although Seattle, Washington — the largest US aerospace cluster and home to Boeing’s main plants — has more than double the total number of jobs of Wichita, the density of aerospace in the Kansas capital is more than 18 per cent of total employment.133 Between the prime manufacturers Cessna, Beechcraft and Bombardier and their subcontractors making large-scale aero-structures, small-scale composite parts, specialised tools or designs as part of the aerospace supply chain, some 35,000 people are employed in aerospace in Wichita.134

Specialised education is also a key attribute of Wichita as an aerospace cluster. Wichita State University (WSU), offers advanced degrees in electrical, mechanical, industrial, and aerospace engineering. Meanwhile, skilled production workers are also trained at the Wichita Area Technical College, which together provide a worker pipeline. The result is that Wichita is an export-driven manufacturing hub unlike many others in the United States.135 Its exports account for more than 20 per cent of its gross metropolitan product, making Wichita the most export-intensive metropolitan area in the United States.136

But this success hasn’t come cheap. Kansas had to provide a US$40 million subsidy in the form of training support in 2011 to keep Textron Aviation (owner of Cessna Aircraft Company since 2014) from moving to Louisiana. In total, Textron is estimated to have benefited from around US$66 million from various state grants around the United States since 1994 and received a further US$203 million in federal grants since 2000.137 Similar subsidies to Boeing were controversial, leading to a decade-long World Trade Organization dispute with Canada, whose Aéronautique Bombardier first filed complaints over unfair US government assistance to airframers.138

Nor is it only state and federal governments expected to subsidise the aerospace cluster in Wichita. Air connectivity is important in the supply of parts for the aerospace manufacturers, leading the Wichita city government to financially underwrite airline services to the city from other parts of the United States in 2009.139

While Wichita is currently the leading aerospace and defence cluster by specialisation (Table 6) without as deep pockets as some larger aerospace states, Kansas may not be able to withstand the winds of change blowing against its aerospace manufacturing sector. Between 2012 and 2016, average annual employment in aerospace product and parts manufacturing dropped eight per cent.140 Boeing ended its 85-year history in Wichita in the middle of 2014, moving work to Texas, Oklahoma and Washington.141 Bombardier has likewise increased its use of facilities in its home city of Montreal in the same timeframe.

Table 6: Top 10 aerospace and defence clusters in the United States by specialisation

|

Economic area |

Specialisation |

|

Wichita, KS |

18.04 |

|

Seattle, WA |

8.14 |

|

Savannah, GA |

7.90 |

|

Tucson, AZ |

7.60 |

|

Charleston, SC |

6.91 |

|

Cedar Rapids, IA |

6.75 |

|

Hartford, CT |

5.28 |

|

Killeen, TX |

3.39 |

|

St Louis, MO |

3.25 |

|

Tulsa, OK |

3.02 |

Case study 2 | AgTech cluster: Front Range, Colorado

Jeff Olson likes to invoke the Second World War. But unlike many other nostalgics, Olson is a progressive. In fact, he is a leader in the field of hydroponics, the indoor irrigation and lighting system associated with marijuana production.

Olson is the founder of Altius Farms, a new vertical greenhouse garden on the outskirts of Denver. Colorado has taken the expertise it garnered in the previously illicit cannabis production and married it with leading edge high-intensity horticulture pioneered in the Netherlands. The World War Two initiative Olsen likes to reference is the Victory Gardens program, where around 40 per cent of America’s fruit and vegetables were grown locally by citizens to help the war effort.142

At present some 97 per cent of leafy greens consumed in Colorado are trucked in from California or Arizona, thanks to the complex interstate produce distribution networks established in the 1950s and 1960s.

The aeroponics movement is championing the sustainability of in-door vertical market gardens supplying local communities. Proponents of tower gardens, where vegetables are grown in hot houses with towering seed beds stacked up to the sky, point to its efficiency. Vertical aeroponics use one-tenth of the land and water of traditional field farming and can deliver yields ten times greater. No chemicals are needed, making all produce guaranteed organic, but with far greater shelf life than produce picked interstate and trucked.

The technology and processes were all largely developed in the Netherlands. The small country produces almost as much fresh vegetables as the United States yet is ten times as productive as US growers with 97 per cent fewer chemicals used.143 Most Dutch aeroponic farms are situated close to Amsterdam Schiphol Airport (AMS). Producers service the just-in-time market for fresh meal kits and ready-to-cook vegetable bags that are commonplace in European supermarkets.

Today the Netherlands is the world’s second largest agricultural exporter, with almost €92 billion (US$106 billion/A$150 billion) of agricultural produce sent beyond its borders in 2017144 This is despite having a population of only 17 million (as opposed to 326 million in the United States) and occupying only 0.4 per cent of the almost 10 million square kilometres (3.8 million square miles) of the area of the total United States.145 The Netherlands does have access, however, to a European common market of 300 million people and European Union trade deals to a further 200 million.146

The Netherlands is still behind the United States in total exports, with US exports of food totalling some US$140.5 billion in the same year. But whereas Dutch exports are high-value, high-margin goods like fresh flowers and produce, US exports comprise mainly of bulk grain products and highly-processed ambient foodstuffs147 where the value is in decline.148

This decline in agricultural export values has, in part, prompted clusters of higher-value agricultural export industries to spring up.149 Colorado has emerged as one of the leading states engaged in high-intensity, high-value agriculture in the United States. The state’s science base is in agriculture, with specialities including agronomy, horticulture and plant sciences.150

Colorado’s research and development in agriculture and food is highly concentrated within the relatively compact urban corridor running from metropolitan Denver to the northern Front Range around Fort Collins.151 In total, there are more than 700 bioscience companies based in Colorado, many with an agriculture focus.152 Rural small businesses, including AgTech companies in Colorado, can access state based financing and grants in addition to USDA Rural Development Agricultural/ Cooperative Programs.153 The US innovation system is characterised by public-private partnerships,154 and previous Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper [2011-2019] has been widely recognised as doing much to encourage innovation and increase Colorado’s reputation for innovative industries.155

The result of this is that although California is the giant of the US AgTech industry, with more than US$2 billion invested in agricultural and food production technology in 2017,156 Colorado is in fourth position when ranked by investment (Table 7). Much of the activity is focused on smaller scale natural food development, rather than mass production.

Table 7: US AgTech investment: value of deals by state (2017)

|

State |

US$m |

|

California |

2,206 |

|

Massachusetts |

817 |

|

New York |

344 |

|

Colorado |

133 |

|

Illinois |

69 |

|

Missouri |

68 |

|

Minnesota |

55 |

|

North Carolina |

40 |

|

Other states |

864 |

These techniques place the state at odds with US agricultural mainstream, which is engaged in increasingly bitter disputes with potential trading partners157 over the safety of previous decades’ scientific breakthroughs.158 The European Union, for example, bans a number of US biotech inventions including microbial meat rinses, genetically-modified grains, biotech seeds, chemical flavourings and endocrine disrupters.159

But Colorado is siding with the natural food side of the debate.160 There is, for example, a growing niche for organic US beef in Europe.161 Many of the finest restaurants in Europe prize the flavour of beef from US cattle breeds but only certified organic US beef is permitted into Europe162 where hormonal growth promotants are banned.163 Similarly, almost all US poultry is prohibited from European markets due to both the high prevalence of salmonella in US chicken164 and also the practice of washing the meat in chlorine baths.165 Instead, near neighbours Canada and Mexico, along with China, are the major US agriculture export markets.

For Olson, the future of agriculture is about people eating increasingly locally. However, increasing demand for fresh, organic produce grown close to air transport links means Colorado is well placed to provide beyond its local population.

Case study 3 | Biomedical cluster: Minneapolis, Minnesota

Up in the frozen north of the Midwest, Minnesota can look (and sound) a little like Scandinavia. More than 1.6 million Minnesotans claim Scandinavian descent and Lutheranism has left its mark in the way business is done.166 There is a strong presence of cooperative businesses from fuel networks to telephone services not found to the same extent in any other state.167

Earl Bakken and Palmer Hermundslie both came from Norwegian heritage.168 When the brothers in-law founded Medtronic in a Minneapolis garage in the post-war years, they brought with them a sense of fairness and equality uncommon in corporate America.169 Bakken invented the first wearable, battery-powered cardiac pacemaker at a time when heart regulators were powered by mains electricity, requiring hospitalisation.170 Bakken changed people’s lives by giving them back mobility.

Bakken is described as the “reluctant millionaire” who strives to return profits back to employees and the people of Minnesota.171 Medtronic manufactures some 40 per cent of the 1.5 million pacemakers sold around the world today, but still lives by the modest strategic vision of making “fair profit on current operations to meet our obligations, sustain our growth, and reach our goals.”172 The company, whose ethos was described by Bakken as “high tech, high touch” places being a “good citizen as a company” among its seven guiding principles.173

Today some 40 per cent of pacemakers sold globally are designed and manufactured in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis–St Paul. The agglomeration is now recognised as one of just four tier one medical technology clusters in the United States (the others being the Boston-Cambridge area of Massachusetts, Southern California and the San Francisco Bay Area). Today some 27,000 people in Minnesota (or 22 per cent of the workforce) are directly employed in medical device manufacture at almost 200 establishments.174

Despite its relatively small size compared to the other leading medical research clusters, the Twin Cities have the highest concentration of medical technology workers in the United States.175 The Minneapolis-St Paul International Airport (MSP) is key to the export success of the sector. Although scheduled passenger flights do depart from the airport, the main reason for customs clearance is for export of high technology medical devices. China is the largest single buyer of medical devices and optical supplies from Minnesota, for example, with exports worth around US$700 million per year to this one market alone.176

The Twin Cities’ medical and life sciences concentration is known as Medical Alley. Medtronic has attracted dozens of companies to establish alongside it in Medical Valley, notably Boston Scientific, Smiths Medical, Ecolab, Takeda Pharmaceuticals and Upsher-Smith Laboratories. The cluster has attracted a further 800 associated healthcare companies such as insurers.177

Of the 6,500 medical device companies in the United States, more than 80 per cent are small or medium-sized. Medical technology, unlike many other manufactured goods, is a high-tech industry where quality is more important than reducing production costs.178

In addition to strong companies, Medical Alley is also home to the Mayo Clinic, one of the most well-known medical research centres in world. The hospital is Minnesota’s largest employer and is a strong reason for the catalysing of the region’s strong medical cluster. This cluster includes University of Minnesota, which ranks ninth among public universities in the United States for research spending, one of seven universities and seven state colleges in the state. This has led to Minnesota being one of the most highly-educated states in the union, with the second highest rate of adults with a bachelor’s degree.179 This level of education, again consistent with Scandinavian levels, is viewed by many as crucial to the Minneapolis region retaining its medical device specialisation.

Minnesota proudly touts its top 10 rankings against other US states on measures of business climate, workforce, innovation, infrastructure and quality of life in addition to education. Being a pioneer in medical devices and bioscience technology with particular strength in patenting appears to have spilled over into Internet of Things, water, food and agricultural innovation.180

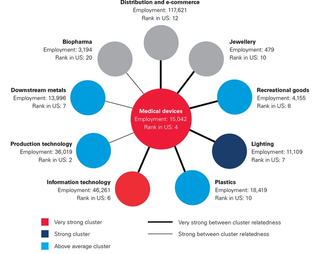

Figure 1 shows the cluster linkages in the Minneapolis Economic Area. Medical devices and IT in this economic area are strong clusters where the concentration of employment in that particular industry is high compared to both the total employment in the state and total US employment in that industry. Additionally cluster relatedness between the medical devices cluster and a number of other industries is strong measured on correlation of employment and establishments, input-output flows and occupational overlap.

Figure 1: Medical devices cluster linkages, Minneapolis, MN Economic Area, 2016

And while the outputs of innovation are strong for Minnesota, it is clear the state government is seeking to build on this by providing small business assistance, emerging entrepreneur loans and R&D tax credits; and more importantly taking an active role in building networks and links to investors and other groups active in their innovation ecosystem.181

Recommendations for Australia

- The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources should work towards concluding pre-clearance protocols with key export markets for future sterile horticultural exports.

In agriculture, despite significant exports, relatively little of high value-add is shipped from airports in Australia. The United States is a world leader in AgTech, the nascent sub-industry at the intersection of agriculture and technology182 and as such can provide much insight into the emerging opportunity of high value, high tech agriculture. Aeroponic production of organic fruit and vegetables, a highly efficient approach of growing plants indoors without soil, should be the model for agricultural exports from Western Sydney Airport. Customs pre-clearance (where goods are processed through the destination country’s customs prior to air-freighting) of high value produce going to key export markets where freshness is prized would support Australia’s reputation for high value horticultural products. - The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration should establish guidelines of surgical implants made by additive manufacturing to enable Australia to gain a toehold in this emerging market.