Executive summary

The climate and decarbonisation policies of leading Democratic presidential candidates suggests the party has become more unified and more progressive on this topic since the end of the Obama administration.

All remaining candidates have pledged to formally recommit the United States to the goals of the Paris Agreement and, with the possible exception of Michael Bloomberg, all have expressed support for the Green New Deal framework.

Taken at face value, this means a Democratic president will seek to not only curtail fossil fuel usage and implement programs to reduce carbon emissions to net zero by around 2050, but also establish ambitious climate-linked social programs for worker retraining, job creation, improved health insurance, and reduced wealth inequality.

While the climate positions of the leading candidates are relatively consistent at a macro level, there are important differences in the details. These include estimates of the cost for reaching net zero carbon emissions, whether the federal government or private industry should take the lead in new energy investment, and the role of nuclear energy and natural gas in a low-carbon future.

Nonetheless, all Democratic candidates present a stark contrast to the Trump administration’s non-existent climate position. If there is a Trump administration climate policy, it appears to be playing down the threats posed by global warming and goading the Democrats into adopting aggressive policies that could prove too radical for moderate voters.

Before the candidates get to contrast their climate vision with President Trump’s lack of interest in the topic, they must first win the Democratic nomination. Differences in climate ambition and policy among the Democratic challengers may yet play an important role in the primary race.

The climate and decarbonisation policies of leading Democratic presidential candidates suggests the party has become more aligned and more progressive on this topic since the end of the Obama administration.

Introduction: A growing consensus on Paris and the Green New Deal

While climate was an early talking point for most Democratic candidates, it has remained more of a slow burn issue rather than one the challengers have used to differentiate themselves from their rivals. Unlike healthcare and immigration, sharp exchanges between the candidates on climate policy details have not been as prominent. The platforms for the major candidates are ambitious and far-reaching when compared with both the mainstream Republican and the Trump administration’s positions.

The major candidates have formally committed to the Paris Climate Agreement goal of restricting global warming to between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius, which means carbon emissions need to be cut in half by 2030 and at net zero by 2050. In adopting this timetable, candidates are acknowledging that within 30 years, renewables would likely need to replace coal and gas for power generation, and battery power would likely need to replace oil for all forms of transportation.

The major candidates have formally committed to the Paris Climate Agreement goal of restricting global warming to between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius, which means carbon emissions need to be cut in half by 2030 and at net zero by 2050.

Most of the Democratic candidates support the Green New Deal, a non-binding resolution co-authored by freshman Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Democratic Senator Ed Markey. The Green New Deal is less proscriptive than the Paris Climate Agreement but provides greater scope for future flexibility and nuance. It does, however, compel candidates to use decarbonisation investments as a tool to transform the US economy in a fashion that promotes wealth redistribution.

The most obvious example of the Green New Deal’s influence is the prominence candidates are giving to compensation schemes — both for displaced fossil fuel industry workers as well as communities characterised as victims of these industries (see Table 1). In an election context, this represents a play for two groups — an attempt to entice miners and refinery workers away from their management, and to encourage a strong turn out from those living near drilling rigs and petrochemical plants.

The emergence of Michael Bloomberg as a leading candidate has created some uncertainty, especially around support for the Green New Deal. While strongly supporting the Green New Deal decarbonisation targets and especially the need to aggressively promote renewables, Bloomberg has described its broader goals as politically unrealistic.

Differences in campaign positions

The degree of consistency in the climate positions of the leading candidates was not predicted by many analysts, as many expected significant differences between progressive and moderate Democratic candidates to emerge. Perhaps one key reason climate has not been more of a battleground is the unexpectedly strong stance taken early in the campaign by Joe Biden in the form of his support for the Green New Deal.1 While this may have disappointed climate activists who wanted to see their cause take a more prominent role in the early debates, differences in climate ambition and strategy could still play a role once the number of candidates has been thinned out.

During the recent Nevada debate, the moderators explored, for perhaps the first time, if the candidates could be split between pragmatism and ambition on climate in a similar fashion to the differences we see on healthcare. While this portion of the debate didn’t generate too many headlines there were clear signs that Bloomberg will argue that winning the election is the primary goal with Warren and Sanders pushing the necessity for bold action and the benefits of the Green New Deal. Biden focussed on his international pedigree which he will use to drive Chinese action on decarbonisation.

Some of the other key differences between the leading candidates are summarised in Table 1. Beyond almost uniform support for the Paris Agreement and the Green New Deal, the table makes clear that the candidates are split on nuclear power and whether gas produced by fracking can be used until renewables become more prominent.

|

|

Biden |

Bloomberg[^2] |

Sanders |

Warren |

|

Zero net emissions by 2050[^3] |

Yes |

Probably |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Green New Deal |

Yes |

Probably not |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Public cost over 10 years (US$ trillions) |

1.7 |

Not specified |

10.9[^4] |

3 |

|

Private contribution (US$ trillions) |

3.3 |

Not specified |

Nil |

Yes, but not specified |

|

Job creation (millions of jobs) |

3 |

Not specified |

10 |

1.2 |

|

Carbon tax |

Yes |

Not specified |

Yes and no[^5] |

Maybe |

|

Payment scheme presented |

Not specified |

No |

Yes |

Not specified |

|

Public ownership of generation |

No |

Probably not |

Yes |

No |

|

Fracking ban |

No |

No federal leases |

Yes |

Yes[^6] |

|

Nuclear |

Yes[^7] |

Unclear |

No |

No |

|

Carbon capture |

Yes |

Unclear |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Another key difference between candidates is the amount of public money they propose to spend on decarbonisation, specifically how much of this will come from the federal government and how much private, state and local investment will be “catalysed”.8 As these differences are further explored in the final stages of the nomination process and during the general election itself, commitment to the principles of the Green New Deal will come into focus. Candidates will be quizzed on how much expenditure and political capital will be spent on all aspects of decarbonisation as well as how they will use the decarbonisation process as a mechanism to transform the way the US economy works. If implemented these changes will impact employment, healthcare, and wealth inequality trends within US society.

What is carbon capture?

Carbon capture is the technology for capturing carbon dioxide from large point sources, such as coal-fired power plants, cement factories or steelworks. The gases from these facilities pass through a separation unit that removes the carbon as liquefied carbon dioxide. Carbon capture is a well-established for removing carbon dioxide from natural gas. The use of carbon capture to reduce carbon emissions from industrial sources is still being developed, meaning it requires government support and subsidy. Carbon capture can also be used for direct air capture — the removal of carbon dioxide from air.

Liquefied carbon dioxide from the process is stored in suitable underground formations. Carbon storage is also well-established in enhanced oil recovery where carbon dioxide is pumped underground to displace oil.

The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (UNIPCC) lists carbon capture and storage as key decarbonisation technologies and the only methods capable of negative emissions — the permanent removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Opposition to carbon capture is based on concerns over leaks from underground storage and that its use will prolong the life of coal and gas-powered generation.

Why is a position on nuclear power important?

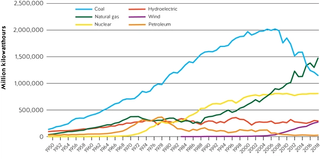

Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren see no role for nuclear energy in a decarbonised future, perhaps recognising longstanding and long-lived progressive opposition to nuclear power.9 They may need to convince pundits and pro-nuclear voters that their opposition is logical rather than an outdated historical reflex.10 As shown Figure 1, just under 20 per cent of US electricity comes from nuclear plants and with an annual availability of ~93 per cent, the nuclear fleet is an important source of stable, zero carbon baseload power. The current reactors were mostly commissioned prior to the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 which means they have an average age of more than 40 years. Several reactors have closed in recent times citing weak power prices and the need to make costly safety-related upgrades. These closures will be offset by two new reactors — Units 3 and 4 at the Vogtle power plant in Georgia — due to come on line soon. The cost for these two, large baseload units (1250 megawatt) is currently estimated at US$25 billion, an 80 per cent increase over the cost estimate when construction started in 2012.

Figure 1. US electricity net generation by sector

New nuclear is expensive and takes a long time to build, so opposition from a potential Democratic administration will not have an immediate impact on the US power landscape. Supporters of nuclear power, however, see a critical role for the next administration in encouraging new capacity to be ready when the existing fleet comes to the end of its practical operating life. This reflects a belief that full decarbonisation of the electricity sector by 2050 will need the reliability of baseload nuclear to balance the intermittent nature of large wind and solar installations. The high cost and extended construction timelines for large scale nuclear is one reason that Joe Biden’s policies support research into smaller scale, sub-200 megawatt nuclear reactors that may have the flexibility to better support a future renewable heavy generation mix.11

A potentially more pressing issue for a new administration will be how to treat the existing fleet. Nuclear reactors in the United States need to be recertified after operating for 40 years with further recertification reviews being required every 20 years thereafter. Most of the current fleet has completed the first recertification and the older units will require a second recertification starting around 2029. Some utilities could decide to close down if faced with a strongly anti-nuclear administration in the White House. A Sanders administration would make this an easy choice because there would be a moratorium on license renewals. While Warren is opposed to expanding the nuclear fleet, she has not ruled out license renewal. This leaves Biden as the most accommodating of ongoing nuclear generation.12

In a primary context, opposition to nuclear will get full support from progressive environmental groups. In the general election, expect Republicans to use nuclear as a climate wedge issue. Some communities may be happy to see their nuclear power plants close but some may value the traditionally secure, high paying jobs.

What happens if fracking is banned?

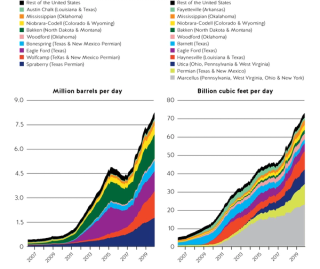

In contrast to nuclear power, a ban or even a sharp reduction in fracking would have an immediate and profound impact on oil and gas production as well as local employment and economic activity across a number of areas across the United States. Horizontal drilling and fracking have been responsible for a 95 per cent increase in domestic oil production and a 60 per cent increase in gas output since 2005.13 This surge has made the United States self-sufficient in oil and gas, revitalised local manufacturing, and played a key role in the 50 per cent reduction in coal consumption. In short, and as Figures 2 and 3 show, fracking has increased substantially and a ban would have major and immediate implications.

Figure 2 (left). US shale and tight oil production

Figure 3 (right). US dry shale gas production

What about restricting anti-fracking initiatives to imposing limits on new fossil fuel extraction from federal lands, as Michael Bloomberg seems to be favouring?14 This would be less disruptive but would still have a significant impact, with 26 per cent of oil and 13 per cent of gas currently coming from lands under Department of the Interior control.15 Such a move would be felt most strongly in western states such as New Mexico, Wyoming, North Dakota, Colorado and Utah. Politically, they are not all swing states, but Colorado and New Mexico, in particular, will be important to the Democrats in the general election for both the Electoral College and the Senate. If a nationwide ban on fracking was initiated, as Warren appears to be considering, domestic oil and gas production would drop by at least 50 per cent virtually overnight, with major impacts in producing states such as Texas, Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Ohio, Alaska and West Virginia as well as neighbouring regions that have experienced flow-on economic benefits (in some cases without the negatives of the drilling itself.

The potential economic and political implications of restricting the use of fracking finally got some air time during the most recent televised debate. Sanders and Warren leaned heavily on the potential for the Green New Deal, a rapid transition to renewables and investment in climate-resilient infrastructure to replace any lost oil and gas jobs. Bloomberg saw an ongoing role for natural gas and fracking at least until coal was completely gone. He also raised stricter regulations on methane leaks as a policy to minimise the worst climate impacts of fracking and the use of natural gas. The Democratic electorate clearly expects its presidential candidate to promote decarbonisation and push strongly pro-renewable policies. Policies to actively curb domestic fossil fuel production will, however, set the scene for a key battle not just with President Trump and his team but with many Americans still unconvinced the country can survive without a strong domestic fossil fuels supply line or nuclear power.

The cost of decarbonisation and who provides the money

While differences on nuclear and to a greater extent fracking are important and will be featured more prominently in the general election, the cost of decarbonisation programs and climate-linked changes to the nation’s key economic structures could be more fundamental to the outcome in 2020.

Table 1 shows that candidates Biden and Warren are promising public funding between US$1.7 and US$3.0 trillion over ten years, with tax and other incentives to promote additional private, state and local investment. The public component of these plans roughly equates to an annual expenditure of between 1 and 2 per cent of US GDP. As a point of reference, this is a similar range that the UK Committee on Climate Change estimated the United Kingdom would need to spend to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050.16 This could be a useful talking point should the candidates be asked to justify the level of proposed expenditure. It could also be used by Republicans linking the candidates to European-style big-spending policies.

Before the successful nominee can shift back to the centre for the general election, the leading candidates will need to answer philosophical questions from an energised Democratic rank and file about whether decarbonisation requires radical restructuring of the US economic model or if US capitalism combined with strong federal oversight remains the best way to harness the nation’s energy and dynamism for such a challenging transformation.

Bernie Sanders is under no doubt that the system needs changing. He is advocating for future renewable generation capacity to be government-owned.17 This is presented as not only the best decarbonisation pathway but also as a means to achieve broad social benefits for the country. This approach makes the Sanders plan an outlier — at US$10.9 trillion over ten years ($16.3 trillion over 15 years), it is the most expensive plan and the only one that excludes significant private investment. The full amount will come directly from the public purse. Under this plan, the US government will build, own and operate much of the nation’s new power generation capacity, leading — in theory — to lower power bills. The Sanders plan looks a lot like a rerun of the 1935 Public Utility Act debate that pitted Roosevelt and his New Deal against Wendell Willkie and the Commonwealth and Southern;18 a comparison, one suspects, that sits well with the Sanders team.

The other candidates, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, endorse a generally more traditional public-private partnership model in which the government combines direct funding with policies aimed at encouraging state, local and private investment. While Elizabeth Warren is not shy in her desire for sweeping economic changes, she appears less willing to use decarbonisation as the vehicle for it. Her climate policy leans more towards federal support of green utilities than ownership.19 The remaining candidates, especially Michael Bloomberg, are perhaps less likely to use decarbonisation as a tool to restructure US economic systems. Their final positions will likely become strong on emission targets and renewable investment and more nuanced on the broader goals of the Green New Deal.

The prospect of increased taxes from millions of new jobs and health savings from cleaner air and water are ubiquitous in the talking points of the Democratic candidates, as is making the rich and guilty pay.

The longer Sanders remains a leading contender, the more likely a public versus private ownership debate will feature in debates and advertising. Perhaps Bloomberg’s involvement in future debates and in the Super Tuesday primaries will be the trigger to have this issue examined in more detail.

Discussion of where the public component of the money will come from is anodyne at this stage of the campaign. Carbon taxes do not have the universal support they once enjoyed but they are still part of the raising revenue discussion. The prospect of increased taxes from millions of new jobs and health savings from cleaner air and water are ubiquitous in the talking points of the Democratic candidates, as is making the rich and guilty pay. Taxes for corporations and the wealthy, according to many of the candidates, will be increased and the fossil fuel industry is likely to see increased fees and litigation to pay for past damage. Echoing the 2008 Obama remark about bankrupting coal plant owners,20 it seems the fossil fuel industry is to help fund its own demise. A greater focus on where and from whom decarbonisation funds will be sourced will, no doubt, be an important topic in the general election. This could be a pivotal question if enough of those who favour lower emissions expect someone else to foot the bill.

Summary

The Democratic candidates appear committed to fighting the general election with policies to sharply ramp up US decarbonisation efforts. Republicans will be hoping that Trump’s rejection of the Paris Agreement has goaded Democrats into handcuffing themselves to politically suicidal goals. Will the average voter see action on climate as welcome and overdue or a threat to jobs and the economy?

While Bloomberg may emerge as a viable moderate candidate on topics like wealth taxes and regulation of the finance industry, his past positions have been strongly anti-coal and he will almost certainly match the other candidates in his zeal to decarbonise the generation sector. What he believes this will cost, how he will pay for it, and how he plans to decarbonise other sectors of the economy remain to be seen. On emission targets, however, a Bloomberg presidential campaign is likely to broadly match the ambition of the other leading candidates.

The Trump administration and Republicans will likely criticise the drama of a climate emergency and highlight the importance of financial management over reckless spending. More robust Republican voices will talk of creeping socialism, rampant globalisation and a Democratic willingness to destroy the foundations of a proud and free United States.

It is not uncommon to hear candidates declare that “this election is the most important decision voters have faced in their lifetime”. Maybe in 2020, this will be a valid claim. If Donald Trump remains the president, the contrast with his challenger on climate change is likely to be dramatic, especially if Sanders or Warren is the Democratic challenger. Of the two progressive challengers in Warren and Sanders, the latter will present the sharpest contrast — to both the incumbent president and to the accepted wisdom of privately-owned generation assets.

With potentially so many points of policy difference, it is still too early to say how critical climate policy will be during the general election. It will be important, but so will immigration, healthcare, and the election of the next Supreme Court judges. It will also depend on who the Democratic challenger is and how their stance is moderated after the primaries are over. Based on the positions of the current frontrunners, voters will have a real choice on how the country prioritises and responds to calls for decarbonisation.

Implications for Australia

If the Democrats win the 2020 election with a robust pro-Paris commitment, Australia will be put in a difficult position. It will be increasingly exposed as a climate laggard with a dismal greenhouse gas reduction performance relative to international peers. A majority of Australians acknowledge climate change as a reality and want the government to take action to mitigate it.21

Under a Democratic president, the United States will join the United Kingdom and a growing number of other nations in formally supporting a 2050 net zero carbon emissions target. Australia’s current coalition government appears very unlikely to join this list but a growing international consensus will put further pressure on a government that has widely disparate views on energy policy.

If the Democrats win the 2020 election with a robust pro-Paris commitment, Australia will be put in a difficult position. It will be increasingly exposed as a climate laggard with a dismal greenhouse gas reduction performance relative to international peers.

Australia’s Labor party is, unsurprisingly, closer to the Democratic position having last week committed to the 2050 target. This commitment sits uncomfortably with statements supporting the continued export of Australian coal and natural gas. A US move to sharply limit fracking will establish a genuine international precedent — it will be the most significant and meaningful example of a fossil fuel producing nation accepting the economic pain of proactively cutting production rather than passively waiting for a gradual demand-side response. Australia will be under pressure to follow suit.

The election of Bernie Sanders and the privatisation of new US generation capability would encourage those supporting a similar approach in Australia. Until relatively recently, public ownership of generation assets was the norm in Australia, an approach revisited by the Turnbull government with the Snowy 2.0 project. While, in theory, this could include a government-sponsored coal-fired plant in north Queensland, a Sanders presidency could push Canberra investment not just in stored hydro but also large-scale batteries and even more unconventional technologies such as commercial production hydrogen, which is the most obvious route by which Australia can offset the loss of coal and gas export income.

Irrespective of who it is, if the next US president is one of the current Democratic candidates and they succeed in driving strong US action on climate, there will be ramifications for Australia. Its current international climate stance will become increasingly untenable, causing tensions on energy policy to continue to grow within both the coalition and the Labor party