Foreword

As the world continues to grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic and we face the strongest economic headwinds in generations, it is only natural that Australia will look to enduring partners, especially in crucial and sensitive fields like investment.

This report makes it abundantly clear that when it comes to investment, Australia has no stronger or more reliable partner than the United States. Total two-way investment amounted to an impressive $1.8 trillion in 2019 — equal in scale to around 90 per cent of the value of the entire Australian share market.

US investment now accounts for over one-quarter of total foreign direct investment into Australia, nearly double the share from our second highest investor, the United Kingdom. What cannot be quantified and shouldn’t be understated is the significant business nous, skills and new technology that has been brought to our shores as a result of this investment.

Our strong investment ties have been underpinned by the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA). This year celebrating its 15th birthday, AUSFTA has been the bedrock of our investment relationship. Since the agreement came into effect on 1 January 2005, the size of the investment relationship has nearly tripled, while two-way trade has also almost doubled.

Strong investment partnerships have been essential to Australia’s success throughout our modern history. Investment has enabled us to grow into the world’s 13th largest economy, supports the jobs of millions of Australians and underpins a way of life that is the envy of the world.

Strong investment partnerships have been essential to Australia’s success throughout our modern history. Investment has enabled us to grow into the world’s 13th largest economy, supports the jobs of millions of Australians and underpins a way of life that is the envy of the world.

As Australia seeks to develop even more sophisticated and high-value goods and services, partnerships and investment by US companies will continue to be vital for Australia’s technology and research sectors, helping to keep us at the cutting edge of productive innovation in emerging industries. Last year services exports to the United States were up 120 per cent reaching $10 billion. The United States is by far Australia’s largest market for business services, IT services, finance and intellectual property.

In agribusiness and food, our abundant natural resources, combined with a dynamic agtech sector are creating exciting potential for growth. In advanced manufacturing, continued investment will be needed to help commercialise groundbreaking work in fields like materials science, medicine and digital technologies.

Meanwhile, Australia’s rich minerals reserves also create fresh prospects for investment and growth. Critical minerals such as lithium and rare earths present huge opportunities for US companies to invest at various stages along the supply chain. Albermarle’s construction of a lithium processing plant at Kemerton in Western Australia exemplifies this.

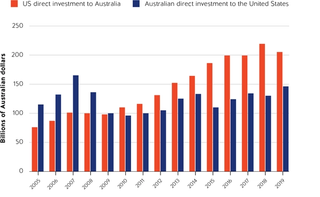

Outbound Australian investment into the United States has also continued to grow, further deepening two-way ties, creating jobs for Americans and diversifying the savings pool of Australians.

Australia’s long-term investment partnership with the United States has continued to thrive because of our complementary economies, shared values, strong institutions and close people-to-people links.

Like any partnership there are challenges, but one thing is for sure, we need this investment relationship now more than ever, as both our economies begin the long road to recovery from COVID-19 and both our nations strive for long-term prosperity.

Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham

Australia’s Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment

Executive summary

In an increasingly fractious global economy, businesses in both the United States and Australia are looking to each other’s markets for stability and strength. Cross border investment between the two nations has remained firm at a time when international investment flows are facing their greatest challenge since the global financial crisis.

The United States Studies Centre produced a landmark study of the US-Australia investment relationship three years ago, roughly a decade on from the global financial crisis. Now, in the midst of a worldwide pandemic and as Australia has entered recession for the first time in 29 years, we find the investment relationship between the two countries is even more important.

This report examines the resilience of the investment partnership between Australia and the United States in a time of growing international turbulence. It identifies some of the barriers which, if they can overcome, would enable further gains.

Australia has been resource-rich but capital-poor for most of its history, hungry for foreign capital to fuel its economic development. The United States is Australia’s largest foreign investor, the largest destination of Australian outbound investment and Australia’s third-largest trading partner. Quite simply, the United States is Australia’s most indispensable and resilient economic partner.

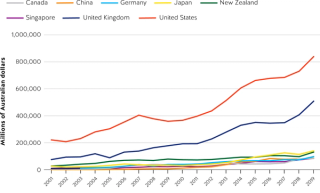

Since the United States Studies Centre (USSC) last looked at the US-Australia investment relationship in 2017, the value of the two-way investment relationship rose by $350 billion, reaching $1.82 trillion. This is equivalent to about 90 per cent of the value of the entire Australian share market, is ten times larger than Australia’s bilateral investment relationship with China and is $627 billion more than Australia’s investment relationship with the United Kingdom, Australia’s second-largest investment partner.

The value of the two-way US-Australia investment partnership has reached $1.82 trillion which is equivalent to about 90 per cent of the value of the entire Australian share market.

The Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA) has been vital to the growth of investment between the two countries. Since the agreement went into effect on 1 January 2005, the Australian-US investment relationship has nearly tripled, having increased by more than $1.2 trillion or 283 per cent.

Today, more than one out of every four dollars invested in Australia from overseas has come from the United States, with the total US investment in Australia totalling $984 billion. In the last five years alone, the stock of US investment has risen by 25 per cent. This is not just a matter of money but also livelihoods: US firms are responsible for some 323,000 jobs in Australia, with annual salaries averaging more than $100,000.

In the other direction, the United States remains the preferred offshore destination for Australia, with Australian investment in the United States now standing at $837 billion and making up 28 per cent of all Australian outbound investment. This too has only grown in recent years: In the last five years, the stock of total Australian investment in the United States has risen by 27 per cent.

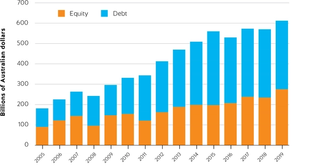

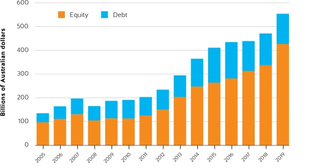

Australian and US pension, retirement, superannuation funds and other financial institutions have also been building their stakes in each other’s debt and equity markets. The overall holdings of Australian stocks and bonds by US investors stands at $611 billion, more than 30 per cent of all foreign investment in Australian securities markets, and nearly double the size of investments of next-ranked United Kingdom. In the other direction, Australian super funds — and their $2.7 trillion pool of funds — among other investors have put $110 billion into the US market over the last six years, lifting their US holdings to $553 billion.1 The increase in portfolio investment has come at a time when global portfolio flows have been weak, with flows dropping by 40 per cent in 2018.

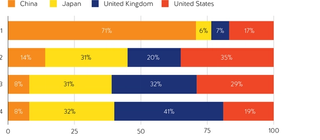

Despite the importance and value of the US-Australia investment relationship, polling in this report found only 17 per cent of Australians realise the United States is Australia’s largest investment partner. Instead the vast majority of Australians — 71 per cent — believe China is Australia’s largest investment partner.

Forging ahead amid a challenging global outlook

The global investment environment has shifted sharply since the initial USSC report in 2017.2 The election of Donald Trump in 2016 was followed by the most far-reaching reform of the United States corporate tax code in 30 years, rising economic nationalism, and conflicts on trade and technology between the United States and China, as well as, a much more aggressive and unilateral approach to international trade. This was before the COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn, which is expected to cut global investment flows by a further 50 per cent.3

While the United States and Australia join much of the world in entering an economic recession in recent months, the global economy was losing momentum even before the COVID-19 pandemic. World economic growth in 2019 was the weakest since the 2008-9 financial crisis.

The first section of this report on the Australian-US economic relationship examines the reasons for the strength of the direct investment relationship at a time of rising economic uncertainty. It considers the role of AUSFTA over its first 15 years.

While the United States and Australia join much of the world in entering an economic recession in recent months, the global economy was losing momentum even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The second section details the economic factors shaping flows of portfolio capital. Investors looking for yield in a world of negative rates have found it both in Australia and in the United States. Australia’s distinctive edge has long been its exposure to Asia and to China through its commodity profile. It offers security with an AAA sovereign credit rating. The current account — long a concern of the ratings agencies — has turned positive for almost the first time in Australia’s history.

While investment has prospered, overall trade flows between Australia and the United States have been relatively weak. Critics have argued the AUSFTA has diverted more trade than it has generated. However, this report addresses the reasons for the weak growth in goods trade and highlights how trade in high technology goods, intellectual property and services has grown strongly.

The third section examines the knowledge intensity of the bilateral relationship. This section also includes a discussion of the impact of the Trump administration’s more assertive approach to trade policy on the bilateral relationship.

The report considers the changes in investment policy over the past three years as national security assumes a higher profile in moderating the globalisation of the 1990s and early 2000s. Finally, it discusses the most important policy steps to strengthen the bilateral economic relationship.

Ultimately, this report highlights the fact bilateral investment relationships are based on the belief the future will be more prosperous than the present times we find ourselves in. The considerable US-Australia investment relationship reflects confidence in the strength of both countries, their political and legal institutions, and the US-Australia relationship more broadly.

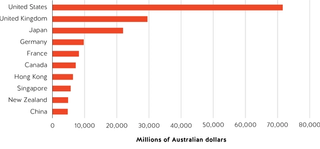

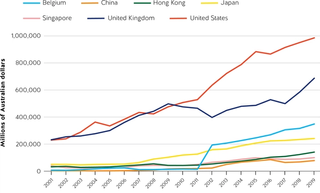

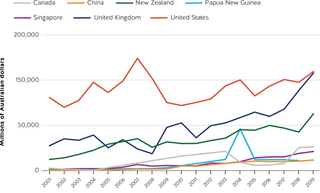

Figure 1. Foreign direct investment into Australia by country (historical cost), 2001-2019

Drivers of direct investment

Why is Australia’s flow of US investment strong at a time when foreign direct investment has been weak globally? US investors have been drawn to Australia’s resources and services sectors, both of which have benefited from exposure to Asian markets. Investment in both directions gains from the certainty provided by the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA), the alliance relationship and the cultural affinity between the two nations.

Australia has long held a special place in the global networks of US business. In the early 1960s, at the end of the first burst of post-war investment, only the United States’ neighbour Canada, its oil supplier Venezuela and the two major European powers of the United Kingdom and West Germany were home to more US investment than Australia.

The investment world is much more complex now. The main attraction for five of the top ten destinations for US investment is the potential for tax structuring, but Australia still ranks as the 12th largest recipient, ahead of China, Mexico, France and Brazil and just behind Germany.4

The US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) reports that the stock of investment by US multinational firms in Australia is US$846 billion, which represents 2.8 per cent of all US offshore investment. This is ahead of Australia’s 1.8 per cent share of the world economy, but the disproportion is more striking in the Asia-Pacific region. Australia captures 18 per cent of US investment in the region, although it represents only five per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP). Australia’s potential as a base for regional operations is among its attractions. Since 2009, US data shows investment in Australia has grown at an average annual rate of 8.1 per cent, which is more than double the 3.9 per cent rate for offshore US investment generally.

The Foreign Investment Review Board shows the United States’ enthusiasm for Australian assets has continued. Its 2018-19 annual report shows record US investment proposals worth $58.2 billion were approved, including big proposals in the services, commercial property and resources sectors. The United States was followed by Canada, Japan, Singapore and China.

Table 1. Foreign direct investment by industry, 2014-2015

|

|

US investment (A$ million) |

% of all US FDI into Australia |

US % share of total foreign investment into Australia |

|

Finance |

224,193 |

39.8 |

28.3 |

|

Mining |

123,610 |

21.9 |

38.0 |

|

Manufacturing |

101,738 |

18.0 |

49.4 |

|

Wholesale |

30,788 |

5.5 |

16.1 |

|

Information |

29,419 |

5.2 |

81.5 |

|

Professional service |

28,359 |

5.0 |

41.7 |

|

Property services |

5,776 |

1.0 |

15.7 |

|

Construction |

5,772 |

1.0 |

10.1 |

|

Retail |

4,353 |

0.8 |

15.5 |

|

Hospitality |

2,930 |

0.5 |

35.9 |

|

Transport |

2,851 |

0.5 |

5.6 |

|

Agriculture |

2,465 |

0.4 |

24.9 |

|

Other service |

455 |

0.1 |

45.3 |

|

Education |

357 |

0.1 |

60.1 |

|

Total |

563,718 |

|

30.3 |

Why global flows have slowed

History helps explain the significant role US business performs in the Australian economy but not why the flow of investment from the United States (and elsewhere) has been strong at a time of general global weakness. The biggest single factor behind the downturn in global foreign direct investment over the last three years has been the “America First” policy of the Trump administration, which has increased policy uncertainty, disrupted trade and sought to encourage US firms to invest at home rather than abroad.5

The US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which took effect in January 2018 and cut the headline US company tax rate from 35 per cent to 21 per cent, had a far-reaching impact on global investment flows. Where previously, there was a large tax incentive for US multinational companies to retain earnings in their subsidiaries, the new law imposed a tax on foreign retained earnings and provided an incentive for them to be repatriated.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that US firms cut their reinvested earnings by US$367 billion, repatriating earnings instead to the United States, in just the first half of 2018 in response to the tax reform.6 Although there was some improvement in the second half, the full year still showed that US multinationals repatriated US$64 billion more than they sent offshore, compared with a US$300 billion investment outflow in the previous year.

The biggest single factor behind the downturn in global foreign direct investment over the last three years has been the “America First” policy of the Trump administration, which has increased policy uncertainty, disrupted trade and sought to encourage US firms to invest at home rather than abroad.

Australia may have been spared this global outflow because its high company tax rate meant there was never the incentive for foreign companies to retain earnings. However, the investment trends for Australia in 2018 were dominated by the presence of a mega-deal, with Disney’s purchase of 21st Century Fox. This contributed to direct investment flows rising strongly from $9 billion to $22 billion in 2018.

It is possible that the disparity between the US headline tax rate of 21 per cent and Australia’s 30 per cent may have a greater impact on investment flows in future, as tax paid offshore is no longer deductible from tax due in the United States. With the caveat that annual investment flows are volatile, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) foreign investment report for 2019 showed direct investment flow from the United States had dropped to just $570 million, which was the lowest since 2005 when another mega-deal involving News Corp skewed the data.

UNCTAD notes that excluding one-off factors which have buffeted global investment, such as the US tax changes and isolated “mega-deals”, foreign direct investment has been anaemic since the 2008-9 global financial crisis, rising at an annual average of just one per cent per year. Over the previous two decades, the stock of foreign direct investment had been rising by about 12 per cent per year.7

The slowdown has several causes. The most obvious is the global financial crisis delivered a shock to business confidence everywhere, with cross-border flows suffering the most as financial institutions retreated from international lending. The effervescent growth of the emerging world has cooled, most notably in China, where there has been a deliberate policy shift away from investment-led growth towards greater fostering of household consumption.

The most dynamic global businesses over the past decade have been the digital giants like Google, Facebook, Apple and Amazon. Relative to the manufacturing conglomerates of earlier decades they are “capital light”.

UNCTAD says this is a structural change to the nature of global investment flows, which it illustrates by showing the superior growth of global payments for royalties, licences and trade in services compared with trade in goods.8

These trends are less evident in Australia — imports of services have risen at an average rate of 5.9 per cent over the last five years.9 While there has been rapid growth in payments overseas for management consulting and professional services, rising at an average ten per cent a year, payment for the use of intellectual property and licensing has only increased at an annual rate of 2.7 per cent (current prices).

Figure 2. Contribution by foreign-owned firms to Australian GDP (industry value added), 2014-2015

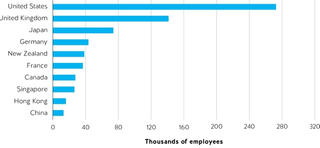

Figure 3. Number of employees of foreign-owned firms in Australia, 2014-2015

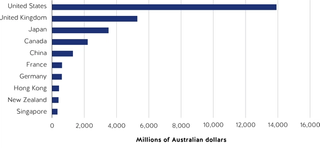

Figure 4. Capital expenditures by foreign firms in Australia, 2014-2015

Australia’s strengths

The striking feature of Australia’s trade profile has been the strength of its exports of both goods and services, primarily reflecting Australia’s position servicing the Chinese market. Led by China’s demand for Australia’s iron ore, coal and LNG, goods exports have been rising at an average rate of ten per cent for the past five years while the growing education and tourist industries have raised services exports by an annual average of 8.8 per cent.

These growth rates have made Australia an attractive investment proposition. An analysis by the ABS based on de-identified 2014-15 tax data shows that 69 US resource companies account for 36 per cent of the value added by US-owned business in Australia while 435 professional services firms account for a further 15 per cent. US manufacturers delivered 16 per cent of value added, a figure that would likely have fallen following the closure of motor vehicle manufacturing in Australia in 2016-17. United States firms are under-represented in the construction, retail, transport and property services sectors.10

Led by China’s demand for Australia’s iron ore, coal and LNG, goods exports have been rising at an average rate of ten per cent for the past five years while the growing education and tourist industries have raised services exports by an annual average of 8.8 per cent. These growth rates have made Australia an attractive investment proposition.

The 2005 Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement has helped to underwrite investment flows in both directions. The most obvious change to the treatment of US investment in Australia was the increase in the threshold before Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) approval was required. This now stands at just under $1.2 billion and has also been extended to other free trade agreement partners. The threshold for everyone else sits at $275 million (although for the duration of the coronavirus crisis, all FIRB thresholds have been lowered to zero which means all foreign investment proposals must be vetted).

Investment lawyers say the higher free trade agreement (FTA) threshold has been less of a benefit than might be supposed, as large transactions are typically channelled through tax-effective administrations such as Bermuda or the Cayman Islands and must go through the standard FIRB scrutiny. The FIRB tests apply to the immediate source of the investment, not the ultimate beneficial ownership.11

Quite apart from the more generous screening thresholds, the AUSFTA provides a framework of legal certainty to give comfort to company boards contemplating investment. There are clauses guaranteeing non-discrimination and largely prohibiting expropriation, with prompt and adequate compensation to be provided in the limited circumstances where it can occur. There is a guaranteed right to free transfer of capital and profits. The two parties are not allowed to impose performance requirements, such as transfer of technology, as a condition of investment approval, while there is a “most-favoured-nation” clause which ensures US investors will receive the benefit of any more generous concessions offered in investment agreements with any other party.

A series of academic studies have highlighted the significant role regional trade agreements have in fostering flows of foreign direct investment.12

The academic literature on foreign direct investment flows also highlights the importance of cultural affinity. A common language, institutional similarity and shared history support foreign investment flows. These are undoubtedly important factors driving Australia’s investment in the United States, as is the size of its market.

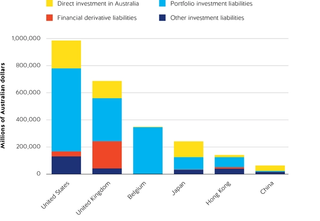

Figure 5. Foreign investment in Australia, 2019

Australians investing in the United States

Australia’s offshore investment only gained scale after the deregulation of capital flows in the 1980s. The level of offshore direct investment rose rapidly from a little more than one per cent of GDP in the 1970s to reach about 30 per cent by 2001. It has remained at about that level since then.

The US market was an early attraction, drawing investment from major Australian listed companies like James Hardie, Westfield and Brambles. By 2000, half Australian direct investment offshore was in the United States.

The US BEA data shows Australian direct investment in the United States has risen by 70 per cent since 2007 to US$252 billion. Foreign direct investment overall in the United States has only risen by 22 per cent in that period.13

Figure 6. Australian and US direct investment stock, 2005-2019

The US investment promotion agency, US Select, says the biggest sectors for Australian investment at present are information technology, business services and healthcare.

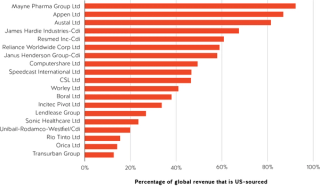

There are more than 40 Australian listed companies with significant operations in the United States and US sales totalling $36 billion. Bloomberg data shows for a number of companies, including Austal, James Hardie, Resmed and Computershare, the US market represents 50 per cent or more of their sales (80 per cent in the case of shipbuilder Austal).

A finding common to all Australian businesses that tackle the US market is its intense competitiveness. To prosper in the United States, businesses must become more productive and innovative. US businesses that come to Australia are similarly highly competitive with an efficiency honed in the world’s toughest market. They help to make the Australian economy more productive both through their own output and by raising the bar for their Australian competitors. As intended when the AUSFTA was negotiated, the intensity of the direct investment relationship supports Australian productivity and living standards.

Company tax traps

Australia has so far retained a high level of foreign investment despite a company tax rate which has become steadily less competitive over the two decades since it was set at 30 per cent. In 2000, the Australian rate was in line with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average. Including state taxes, the US rate is now 26 per cent while Australia’s second-largest source of foreign investment, the United Kingdom, has a 19 per cent company tax rate.

In the absence of any reduction on the Australian company tax rate (and neither of the major political parties has any policy to do so), tax theory is clear a higher company tax rate will result in a lower flow of foreign investment. Academic research on the actual drivers of foreign investment decisions presents a more complex picture, showing other factors may have a countervailing importance, but most studies point to the expected result.14

The reality of continued strong foreign direct investment, including from lower tax jurisdictions like the United Kingdom and now the United States, shows there are other factors at work. The relative tax rates between the home country of a multinational and the host of its subsidiary would be expected to have an impact when the head office is considering allocating new capital. But if it funds a new operation from retained earnings in the subsidiary, then the tax comparison is less important.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has noted a large share of the unprecedented investment in the resources boom, which saw capital stock in the resources sector almost quadruple, was funded from the retained earnings of foreign owners of resource companies. This meant in many cases, “these capital flows are notional flows only as the funds have not left Australia.”15

This insight about the difference between fresh capital allocations and reinvested earnings has been used to explain the failure of some studies to find a greater effect of tax rates on FDI decisions particularly when the United States was adopting a worldwide system of corporate taxation where companies got credits against their high US taxes for the tax they paid elsewhere.16 Under its new territorial tax scheme, a multinational pays the tax due in the host country and does not get taxed in the United States for any dividends it returns. Under this system, multinationals may make harsher judgements about high tax jurisdictions. The fall in US direct investment flows to Australia in 2018-19 may be the first evidence of this.

The power of capital flows

US and Australian investors and borrowers draw advantages from participating in each other’s equity and debt markets.

Foreign direct investment generates jobs and growth and is a stable source of capital which is unlikely to be suddenly repatriated in a crisis. However, portfolio investment — the flow of funds from financial institutions into share and bond markets — is also important to the national economic wellbeing.

International portfolio investment flows make it possible for companies to finance themselves free from the constraints of their domestic market, and let governments manage their finances, including running budget deficits when necessary, without forcing domestic interest rates higher. International capital flows also allow investors to diversify their assets and lower their risk. Australian superannuation funds have about half their fixed-interest and equity holdings in overseas markets.17

The turnover, as global and domestic investors trade shares and bonds, is enormous, with the ASX trading more than $4.8 billion in shares every day while the trade in Australian government bonds reaches about $5.2 billion a day.

For both inflows and outflows of investment capital, Australia’s relationship with the United States is paramount. US investors account for almost half of all identified foreign investment in the Australian share market while Australian super funds and insurance companies have a similar share of their offshore share market investments in the United States.18

There is a similar strong bilateral preference in bond markets. US investors account for 28 per cent of foreign investment in Australian fixed-income markets while Australian institutions have 32 per cent of their offshore holdings of interest-bearing securities in the US market. Each market is offering the other something unique.

US economic dynamism

The United States has been the exceptional outperformer since it emerged from the financial crisis. Over just the past decade, US companies Google, Apple, Amazon and Facebook have achieved an unrivalled dominance of the technologies that are revolutionising the way we live and work. Behind them stands a phalanx of app developers, chip manufacturers and network specialists, many with near-monopolies in their chosen fields.

While the United States has felt the pressure of Chinese and other emerging nation competition in much of its traditional manufacturing industry, it has achieved a leadership in the transformative technology of our age which rivals and arguably surpasses that achieved by Henry Ford and Alfred Sloan in the 1920s and 1930s, IBM in the 1960s or Microsoft in the 1980s.

The US embrace of technology has also enabled it to shake off its post-war energy dependence on the politically febrile Middle East. Fracking — still banned or tightly limited in much of Australia — has made the United States increasingly self-sufficient in oil and gas. In late 2018, the US became a net exporter of oil and refined fuel for the first time since 1949.19

These core strengths have delivered a dynamism to the US economy which is unmatched by other advanced economies.

The S&P 500 index surpassed its pre-crisis high in 2013 and by February this year, ahead of the coronavirus slump, was showing a gain of more than 100 per cent, while the technology-focussed Nasdaq Index had made gains of 400 per cent.

Any diversified share portfolio for an Australian investor needs a position in the United States equities market.

The ABS shows since 2012, the stock of US equities owned by Australian institutions has been rising in value by an average of 14 per cent a year, which has been sufficient to lift the value of holdings from $150 billion to $336 billion.

US investors account for almost half of all identified foreign investment in the Australian share market while Australian super funds and insurance companies have a similar share of their offshore share market investments in the United States.

The performance of the Australian equities market has been modest by comparison, and in February 2020, the S&P/ASX 200 was still less than 15 per cent above pre-financial crisis highs. The COVID-19 crisis hit all share markets. The US market fell 33 per cent by late March but has since recovered and, by the end of May was only ten per cent below its peak. Although the pandemic hit the United States much harder, Australia’s market fell further, dropping 37 per cent and at the end of May was still down 19 per cent from its peak.

The Australian market has its own strengths, however, particularly in the resources and energy sectors where Australia has become the leading supplier to world, and particularly Chinese, markets. US investment in Australian equities rose sharply during the resources boom and has held steady at between $200 billion and $240 billion since 2014.

The US debt market is, if anything, even more remarkable than US equities. It is the largest and most liquid market in the world and is backed by sound legal and market institutions.20 They are qualities which enable it to raise around US$4 trillion a year for government, municipal and corporate borrowers. They have also made US markets the benchmark for safety. Even during the heart of the 2008-9 financial crisis which was centred on the United States, investors globally rushed to buy US government bonds, believing they offered superior security. The same has been true during the coronavirus crisis.

This reputation has survived ratings agency S&P Global stripping the United States of its AAA credit rating in 2011 because of its continued large budget deficits.

At a time when yields are low everywhere, with a significant portion of European sovereign and corporate bonds delivering negative returns, the US bond market is still offering a positive yield, despite the impact of the pandemic.

The switch in US monetary policy early last year from the tightening which had long been expected as US economic activity strengthened to an easing in response to continued low inflation delivered significant capital gains to investors in US fixed-interest markets over the past year. Those gains have been multiplied by the further rise in bond prices during the pandemic. Australian investors’ stocks of US debt assets stood at $127 billion at the end of 2019.

Figure 7. US portfolio investment in Australia, 2005-2019

Figure 8. Australian portfolio investment in the United States, 2005-2019

Tapping each other’s debt markets

Australian companies also make use of the US debt market to raise funds both to finance their overseas operations and to make use of lower transaction costs in the US market, with funds raised in US dollars swapped back into Australian currency. US debt markets are quite accustomed to corporate bond issues of US$10 billion or US$20 billion and can easily accommodate the US$1 billion to US$2 billion issues from Australian names without the least impact on prices. RBA research shows Australian banks obtain about a third of their offshore funding from the United States.21

As well as the big banks, the US markets have been tapped by corporates such as BHP, Fortescue (which both have US dollar revenue), Telstra and APT Pipelines, with the last attracted by the ability to obtain well-priced long-term funding to match its long-lived assets. The total pool of US dollar bond issues by Australian banks and corporates is up to US$350 billion.

Australian companies make use of the US debt market to raise funds both to finance their overseas operations and to make use of lower transaction costs in the US market, with funds raised in US dollars swapped back into Australian currency.

Australian companies also access the US private placement market for long-term funding out to 40 years sourced from individual investment funds, often with less onerous documentation than would be required in Australia. Australian banks and major corporates carry good credit ratings and are well regarded in US markets.

There is also active interest by US investors in Australian fixed-income markets following the financial crisis. IMF figures show Australia accounts for a surprisingly high 4.8 per cent of US investment in global fixed-interest securities.22

There was a step-change in US holdings of Australian debt securities following the financial crisis. Having hovered around $110 billion in the preceding years, it rose to $310 billion by 2014. The US accounts for 28 per cent of foreign investment in Australia’s bonds.

US companies also make use of Australian dollars to raise funds. Although Australian markets are small relative to the vast pools of capital available in the United States, US businesses make issues in Australian dollars both to fund Australian operations and to exploit arbitrage opportunities in swap markets to gain favourable rates. Use of the Australian dollar market can be advantageous for tax reasons for foreign companies with Australian operations.

Of Australian dollar non-financial corporate bonds outstanding of about $60 billion, approximately 40 per cent are foreign issuers, with US names including Apple, Verizon, McDonald's and Coca Cola.

Figure 9. ASX-listed companies with US revenue, February 2020

Economic flexibility

The global demand for Australian dollar assets and liabilities provides great flexibility to the economy. Australian entities can borrow internationally, swapping the proceeds back into Australian dollars with counterparties that want Australian dollar exposure. This eliminates the risk-averse exchange rate movements would blow out the debt repayment liability and frees banks and companies to obtain funding wherever it is most advantageous.

Australian government debt issues have been attractive to foreign (and US) investors with Australia standing as one of just 11 countries to retain its AAA credit rating from the three major ratings agencies in the wake of the financial crisis.

S&P Global put Australia’s credit rating on “negative watch” in the wake of the coronavirus, which has swept away the government’s hopes of returning the budget to surplus. However, Australia’s debt position remains favourable relative to other advanced nations, and the Australian Office of Financial Management’s rate of fresh bond issues of about $5 billion a week since the crisis began has been well supported by the market.

Australia’s debt position remains favourable relative to other advanced nations, and the Australian Office of Financial Management’s rate of fresh bond issues of about $5 billion a week since the COVID-19 crisis began has been well supported by the market.

The Australian Office of Financial Management reports foreign investors hold about 60 per cent of Australian federal government bonds, down from a 2012 peak of 75 per cent. Although it cannot further identify its foreign investors which mostly use nominee companies, it estimates North American demand accounts for about 12 per cent of the monthly turnover in the secondary market.23

The improvement in Australian federal and state government finances ahead of the coronavirus pandemic and the fall in business investment following the resources boom reduced Australia’s historic dependence on global capital markets. Higher savings and lower investment brought Australia’s current account back to surplus in 2019 for the first time since the 1970s. Gross investment as a share of Australian GDP has declined, while national saving has increased, closing the domestic investment-saving gap. Deficits have been the norm for Australia throughout its history. Whether Australia remains a net exporter of capital amid a global recession is not yet clear, however, the gross flows of foreign investment through its debt and equity markets will remain substantial as will the Australian use of US debt and equity markets.

When the Australian dollar was floated and capital controls were removed in 1983, it was anticipated removing decisions about the exchange rate from the cabinet table would make the economy more flexible. But it was never dreamt a vast global financial market, led by US investors, would develop such an appetite for Australian dollar assets and liabilities the Australian dollar would become one of the most widely traded currencies in the world.24

Australia’s integration into global financial markets spreads both the risks and the returns from the Australian economy to investors around the world while opening global financial markets to Australian investors and borrowers.

Figure 10. Total stock of all foreign investment into Australia by country (historical cost), 2001-2019

The determinants of Australian inward foreign direct investment transactions

What do they imply about the success of AUSFTA 15 years on?

Stephen Kirchner, Director, Trade and Investment Program, United States Studies Centre

Australia has been an active participant in the global trend towards increased cross-border investment liberalisation in recent decades. One of the main instruments Australia has used to promote increased foreign direct investment is bilateral investment treaties and free trade agreements, including the landmark Australia-US Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA) that came into force 15 years ago.

There has been surprisingly little empirical work on the determinants of inward foreign direct investment in Australia and the effects of Australia’s free trade and investment agreements on these flows.25

Back in 2012, I estimated a model of inward foreign direct investment transactions for Australia using data from September quarter 1988 until December quarter 2004, just before the AUSFTA came into effect from the beginning of the March quarter 2005. I then compared actual FDI transactions to those forecast by the model through to the June quarter 2011. I found that inward FDI transactions were $74.7 billion higher by the June quarter 2011 than would have predicted by the evolution of the economic fundamentals since the end of 2004.

One of the main instruments Australia has used to promote increased foreign direct investment is bilateral investment treaties and free trade agreements, including the landmark Australia-US Free Trade Agreement that came into force 15 years ago.

The increase in inflows to Australia relative to the model’s forecast can be attributed to the AUSFTA both directly and indirectly. The direct contribution comes from the liberalisation of screening arrangements for US investment, the largest source country for Australia’s FDI inflows. However, the agreement also set a benchmark for the investment provisions in Australia’s subsequent FTAs with other countries, while also requiring that Australia rationalise its broader screening thresholds and raise its standards for the treatment of foreign investment.26

In this note, I updated the model I estimated in 2012 to see if it still broadly explains Australia’s FDI inflows, noting any parameter changes. I tested for a structural break to see whether it coincides with the AUSFTA. I then compared actual FDI inflows to those forecast by the model estimated until the end of 2004 to estimate the implications of AUSFTA and the broader changes it brought about for inward FDI transactions. The model I used in 2012 was based on those factors likely to determine the absolute and relative rates of investment return in Australia (see Appendix).27

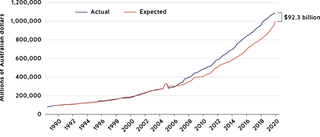

While my prior work was estimated over the period to the end of 2004, it can still be used as the basis for comparing actual foreign direct investment transactions with those that would have been expected conditional on the explanatory variables evolving as they did after 2004. Note that Figure 11 shows how the stock of FDI would have evolved based on transactions only, abstracting from exchange rate and other valuation effects on the existing stock of FDI.

Figure 11. Actual versus expected inward foreign direct investment in Australia

Figure 12. Foreign direct investment in Australia relative to forecast

After re-running the model, I determined that as of the March quarter 2020, the stock of FDI is $92.3 billion higher than would have been expected based on the model estimated to the end of 2004. While this is within the standard error of the model, it is nonetheless consistent with Australia improving its performance on inward foreign direct investment from 2005 relative to what would have been expected based on the subsequent evolution of economic fundamentals. Note that actual FDI initially underperformed expectations before exceeding those expectations from Q1 2006.

It should be noted that the gap been actual and expected FDI has narrowed somewhat in recent years, as the model has over-predicted FDI inflows. This is consistent with a global slowing in FDI flows since the election of President Trump and is a trend that bears watching. While the AUSFTA contributed to an overall improvement in the foreign investment climate in Australia, a trend to slower FDI growth globally could be expected to weigh on inward FDI to Australia relative to fundamentals.

Trade ties tested

The United States retains an important place in Australia’s trade profile, despite the increased trade with China over the past 15 years. However, Australia faces risks as the multilateral trading system under the auspices of the World Trade Organization comes under stress.

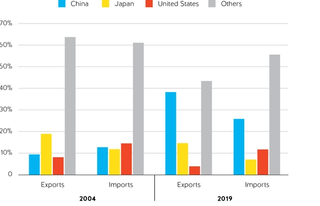

When AUSFTA entered force in 2005, modelling predicted the greatest gains would come from investment and improved productivity, but it was still expected trade would show material gains. Few would have predicted the United States’ share of Australia’s goods exports would halve from eight to four per cent over the next 15 years. The US share of Australia’s imports has held up better, dropping from 15 to 12 per cent. However, with China growing much faster than the United States, the US share of Australian trade was bound to fall.

The past 15 years have brought the unparalleled boom in Australia’s terms of trade (export prices compared with import prices), the biggest ever surge in its capital stock and the nation’s emergence as the world’s dominant provider of minerals and energy, all geared to the needs of a Chinese market which has also delivered rapid growth to Australia’s services industry. Iron ore exports rising fourfold to 800 million tonnes, LNG exports soaring from three million tonnes to 75 million tonnes and education earnings going from $6 billion to $33 billion are a few markers of an historic transformation.

Over the past 15 years, the overall volume of Australia’s trade has risen by 98 per cent, which is double the growth in global trade and almost three times the growth for advanced nations.28 Propelling the exchange rate from its post-crisis low of US64c to a 2011 high of US$1.11, the resources boom brought huge changes to Australia’s trade patterns and put great pressure on its trade-exposed manufacturing sector.

The United States is by far Australia’s largest market for business services, IT services, finance and intellectual property.

Throughout the upheaval, the United States has remained a crucial market for Australian business and the most important supplier of the goods and services which contribute to Australia’s status as an advanced country. In both directions, trade has prospered in goods and services with the highest technological and intellectual content. The United States still stands as Australia’s third-largest trading partner, with a two-way flow of goods and services of $74 billion, of which $27 billion is services trade.

Australia’s exports of farm goods and resources to the United States last year of $3.8 billion were almost unchanged from 15 years previously. This lack of movement overall in primary goods exports conceals some industry changes: beef sales have done well while wine sales have struggled. However, exports of manufactured goods have risen by almost 90 per cent over the period, with the biggest gains registered among the most sophisticated products. Aircraft parts, pharmaceuticals and telecommunications equipment have been among the strongest performers.

Sales of services to US customers are up 120 per cent reaching $10 billion last year. The US is by far Australia’s largest market for business services, IT services, finance and intellectual property. Tourism and education are the only services sectors where China is Australia’s dominant market. Much of the services trade is conducted through the affiliates companies of each country have established in the other. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis puts the sales of Australian affiliates in the United States at US$57 billion in 2017.

Figure 13. Shares of Australian exports and imports, 2004 and 2019

Although the mercantilist approach to trade which increasingly shapes world trade policy sees exports as a positive and imports as a negative, trade economists have long argued the goal of enterprises is to make profits and for consumers is to improve their standard of living. Imports deliver both, providing businesses and individuals with goods and services which better meet their needs at a lower price than could be obtained domestically.

Australia imports many items from the United States which are simply not available elsewhere. Medical instruments, telecommunications and computing equipment, civil engineering plant and analytic tools feature near the top of the list of manufactured imports. Among services imports, the United States is by far Australia’s largest supplier of intellectual property, business services, financial services and recreation/personal services.29

The Australian affiliates of US companies are vital contributors to the economy. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates more than 1,000 US affiliates in Australia recorded sales in Australia of US$153 billion in 2017. They spent US$940 million on research and development, which was equivalent to approximately eight per cent of all business research and development spending. The research investment by US companies peaked at $1.2 billion in 2014 and has fallen since, possibly in response to cuts to the government’s research tax incentives for larger companies. It may also be that the closure of Australia’s motor vehicle industry had an impact, although manufacturers including Ford and, until recently, General Motors, retained design and research functions in Australia.

The ambition of AUSFTA

The idea the trade agreement would bring greater integration of the two economies, giving an economic dimension to the strategic alliance, was embedded from the outset. It was also believed the bilateral flow of investment would support productivity.

The trade agreement had broad goals. Australia’s trade minister at the time, Mark Vaile, said beyond the direct benefits of trade liberalisation, the agreement would:

- Attract additional US investment to Australia, boosting employment and productivity

- Bring a greater integration of business between the two markets with gains coming from research and development, materials sourcing, marketing and the use of technology

- Fost “competitive liberalisation” through demonstration effects for other World Trade Organization (WTO) members

- Cement the Australian and US alliance, recognising the rising threats to security in the Asia-Pacific region.30

Critics argued the agreement would cause trade diversion, with Australian and US firms buying from each other in preference to sourcing from third countries which may offer better value goods and services but do not have the preferential access delivered by the agreement. This concern has been expressed by the Australian Productivity Commission.31 However, Australia now has trade agreements with Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Thailand, Singapore and Indonesia (among others), covering about 80 per cent of its trade. As a result, the issue of trade diversion arising from any of them has been greatly reduced.

Negotiations on most of these trade agreements were initiated under the Howard government in the early 2000s. The Howard government’s 2003 foreign policy white paper stated “while the emphasis of the government will remain on multilateral trade liberalisation, the active pursuit of regional and, in particular, bilateral liberalisation will help set a high benchmark for the multilateral system. Liberalisation through these avenues can compete with and stimulate multilateral liberalisation.”32

Figure 14. Australian outbound foreign investment (stock), 2001-2019

They formed part of a proliferation of preferential trade agreements focussed in the Asia-Pacific region which developed as negotiations on a new trade round under the World Trade Organization were faltering. Since 2000, there have been 220 preferential trade agreements registered with the WTO.

In 2006, the leaders of APEC agreed to start negotiations on a Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP), which would unite its members in a single free trade zone. President of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, Fred Bergsten, argued the FTAAP would be able to subsume the “spaghetti bowl” of preferential trade deals under a single umbrella.33

Although little progress was made as the global financial crisis swept the world, discussions started on two regional trade groups, either of which could be the foundation for a broader FTAAP type group. The United States led plans for a Trans-Pacific Partnership bringing together a selection of APEC members: Japan, Canada, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Singapore Malaysia, Vietnam, Brunei, Australia and New Zealand. It was an ambitious deal specifying high levels of protection for intellectual property, competitive neutrality for state-owned enterprises, regulation of online commerce and protection of foreign investors.

It notably did not include China, which instead encouraged a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), to include those in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as well as Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand, but not the United States.

The United States withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership following the election of Donald Trump in 2016 (his rival Hillary Clinton also promised to withdraw). The remaining members concluded an agreement without the US participation, suspending some of the conditions the United States had insisted on intellectual property, procurement and dispute settlement. Negotiations on RCEP are approaching completion, with India having withdrawn from the agreement.

These regional agreements represent zones of harmony in a much more conflicted global trading world. Negotiations to update the WTO’s mandate to reflect the growth in trade in services, intellectual property and the emerging e-commerce which began in 2001 in the Qatari capital of Doha were effectively abandoned in 2015.

Managing the US shift to unilateralism

The WTO’s ability to resolve disputes between its members has been frustrated by the United States’ refusal to approve new judges to its appeals panel, which no longer has the minimum number of judges to hear cases. While a workaround has been developed by some members, including the European Union, China and Australia, it is doubtful the United States would accept its authority. The Trump administration has abandoned the United States’ previous preference for multilateral approaches to global trade issues in favour of a more assertive unilateral approach with individual trade partners, showing a preparedness to use the tools of trade protection to achieve its objectives.

Australia has been able to call on its deep relationship with the United States to gain exemption from tariffs the United States imposed on the steel and aluminium imports from other trading partners. Initially, the Trump administration had said there would be no exemptions from the tariffs of ten per cent on aluminium imports and 25 per cent on steel, arguing the protection was required for reasons of national security. Australia argued, and the US Government accepted, Australia had demonstrated it was a loyal security partner.

Table 2. Australia’s goods trade with the United States

|

|

2018 ($ millions) |

Five-year growth (%) |

|

Exports |

|

|

|

Beef |

1,756 |

3 |

|

Aircraft and parts |

1,074 |

7 |

|

Pharmacy products (excl. medicine) |

1,059 |

87 |

|

Other meat |

993 |

15 |

|

Aluminium |

518 |

38 |

|

Wine and other alcohol |

448 |

-1 |

|

Miscellaneous manufactures |

391 |

15 |

|

Medical instruments |

335 |

-2 |

|

Analytic instruments |

291 |

9 |

|

Telecommunications equipment |

284 |

6 |

|

Total |

13,440 |

5 |

|

Imports |

|

|

|

Motor vehicles |

2,041 |

2 |

|

Aircraft and parts |

1,250 |

87 |

|

Medical instruments |

1,187 |

7 |

|

Telecommunications equipment |

1,186 |

NA |

|

Pharmacy products (excl. medicine) |

1,110 |

21 |

|

Analytic instruments |

1,107 |

1 |

|

Medicines |

1,102 |

2 |

|

Civil engineering equipment |

976 |

-1 |

|

Computers |

731 |

8 |

|

Trucks |

724 |

-3 |

|

Total |

33,273 |

4 |

Some felt by obtaining an exemption, Australia had legitimised the United States’ protectionist action when it should have been protesting the erosion of the rule-based global trading order.34 However, the Australian Government has expressed some sympathy for the United States’ belief the world trade system is failing, with Prime Minister Scott Morrison saying many of the US concerns are legitimate.35

Australia is exposed to collateral damage from the United States’ pursuit of bilateral deals. The ceasefire agreement in the protracted trade war between the United States and China, struck in late 2019, requires China to lift its purchases of United States goods by US$200 billion relative to 2017 levels over the course of 2020 and 2021. China’s farm imports from the United States are to rise from US$10 billion to US$40 billion over the two-year period while its energy purchases are to rise from US$6.8 billion to US$33.8 billion.36 Early evidence of the danger for Australia was China’s imposition of prohibitive anti-dumping duties on its barley exports which were replaced with supplies from the United States under the bilateral trade deal. There is potential for broader disruption as China attempts to meet its obligations.

These are more difficult days for trade generally as they are for the global economy. Australia’s ability to repeat the rapid growth of the past decade and a half must be doubted, even once the coronavirus crisis has passed. World trade volumes have shown no growth at all for more than two years and are expected to fall sharply over 2020. US trade volumes have not grown since late 2017 while Chinese trade volumes have been static since mid-2018.37

Nations almost everywhere are resorting to protectionist measures of some sort to defend the export-exposed sectors of their economies. The task for Australia is to resist these pressures while working through multilateral forums and its bilateral relationship with the United States to reaffirm the priority of an agreed global framework to lower the barriers to trade.

Results from a survey of Australians about foreign investment

Fewer than one person in five can correctly identify the United States as Australia’s largest source of foreign investment.

Despite the widespread presence of familiar US brand names, such as McDonald's, Amazon, or Apple, 71 per cent of Australians mistakenly nominate China as Australia’s biggest source of investment.

Annual investment flows are volatile, but the Australian Bureau of Statistics records that over the last five years, US firms pumped $66.8 billion in fresh investment into Australia, compared with only $14.2 billion from China in 2017-18.

Despite the widespread presence of familiar US brand names, such as McDonald's, Amazon, or Apple, 71 per cent of Australians mistakenly nominate China as Australia’s biggest source of investment.

A United States Studies Centre survey of 1,054 Australians conducted by YouGov found that there is a good public understanding of Australia’s trade relationships, but widespread ignorance about international investment.

Asked to rank Australia’s largest trading partners, 81 per cent correctly named China as the largest, while views were divided over whether Japan or the United States was second-largest with 40 per cent naming each.

Over the past decade, China has become Australia’s dominant trading partner, accounting for 26.4 per cent of its two-way trade in goods and services, followed by Japan with 9.9 per cent and the United States with 8.6 per cent.

While there have been some high profile and controversial Chinese investments in Australia, the flow of Chinese investment in Australia has never exceeded that from the United States.

However, only 17 per cent of people nominate the United States as the largest source of investment. Only eight per cent of respondents correctly placed China as Australia’s fourth-largest source of foreign investment, ranking behind the United Kingdom and Japan.

The constant flow of high levels of investment from the United States means that it is by far the dominant foreign presence in the Australian economy. Its accumulated investment is now $983 billion, followed by the United Kingdom with $686 billion. China trails, ranking ninth, with investments of $78 billion.

Australians overwhelmingly and incorrectly rank China as Australia's largest investment partner

Survey question: International investments include buying fixed assets (such as land, property and physical plant), shares in companies, and financial instruments (such as government and corporate bonds and loans). Which of the following do you think is the largest source of international investment in Australia? Please order each country, with Australia’s largest source of international investment ranked 1, and the smallest ranked 4.

Foreign direct investment at the intersection with national security

Traditionally regarded as a mainly economic policy issue, foreign direct investment is increasingly seen through the lens of national security, reflecting the strategic unease in the west about the rise of China. Australia and the United States have been at the forefront of efforts to tighten national security controls.

Australia and the United States share common concerns about the potential threat to national security posed by foreign control of critical infrastructure, technology and data. Both nations have introduced new legislation to give government greater ability to monitor and control the activities of foreign enterprises behind their national borders. Both nations are reacting to the emerging strategic competition with China and are arming themselves with the legal tools to control the risks posed by a potential adversary gaining access to assets which are deemed of value to national security.

It is a global trend. The OECD recorded last year nine of the world’s ten largest economies had announced fresh policies to deal with national security risks in foreign investment between 2017 and 2018.38 The OECD says the upsurge in regulation is partly due to the growth of foreign direct investment on the whole. Until the 1990s, foreign direct investment took place mainly among allies and amounted to less than ten per cent of GDP. It is now up to 40 per cent of GDP and is coming from countries with very different governance systems and strategic interests.

Other factors contributing to the increased focus on national security include the appreciation the privatisations which began during the 1980s and 1990s often left critical infrastructure in foreign hands while technology has turned data, and the potential to manipulate it, into a strategic asset. The OECD says in addition to concerns about espionage and sabotage, there is also a concern about preserving a diversity of suppliers and about access to advanced technology.

A lack of focus has made foreign investment decision-making in Australia vulnerable to lobbying from protectionist forces.

With the growing attention on national security risks, more international takeovers are being blocked. UNCTAD records between 2016 and 2019 identified 20 planned foreign investments which were blocked or withdrawn for national security reasons. All but four of them were from China or Hong Kong. UNCTAD estimates in 2018 alone, investments worth US$150 billion, equivalent to 12 per cent of all identified foreign investment, were blocked or withdrawn.39

Australia and the United States have both employed screening mechanisms to vet incoming investment for a long time.40 The United States’ Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is led by the Treasury Secretary but includes members of Justice, Homeland Security, Commerce, Defense, State and Energy Departments, as well as the Trade Representative and the Science and Technology Policy Office. Its mandate is to review the national security implications of foreign investment proposals which must be presented for vetting if they meet certain conditions.

Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) has a much broader mandate to ensure foreign investment proposals are “not contrary to the national interest”, which is not further defined.41 The board makes recommendations to the Treasurer, who has the final decision-making power (and is not open to legal appeal).

A lack of focus has made foreign investment decision-making in Australia vulnerable to lobbying from protectionist forces.42

The Australian Government has announced plans to legislate to introduce a new national security test for foreign investments. Any foreign investment for more than ten per cent in a “sensitive national security business” will require FIRB approval, regardless of the amount. The legislation, to take effect from the beginning of 2021, will include a definition of what industries are covered, but it is expected to include telecommunications, infrastructure, data centres and anything related to defence supply chains. The legislation will include tough penalties for breaches of conditions imposed by the FIRB, including the potential forced divestment.

The Australian focus on national security has sharpened since the appointment of David Irvine as Foreign Investment Review Board Chair in April 2017. He had previously led Australia’s two key intelligence agencies, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) and the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) and had also served as an ambassador to China.

The FIRB refers investment proposals to other government agencies for their comments before recommendations are made to the Treasurer. Since 2015, ASIO has played a much more active role, recording in its latest annual report it had vetted 275 investment proposals over the previous 12 months. This represents around a quarter of all foreign investment proposals (excluding residential real estate). Until four years ago, it was rare for conditions to be attached to FIRB approvals, however, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg recently revealed 80 per cent of approvals (by value) had conditions attached last year, with FIRB now having around 1000 conditional approvals on its books.43

Figure 15. Australian outward foreign direct investment, 2001-2019

Concern the security of Australia’s infrastructure was not adequately monitored led the government to establish the Critical Infrastructure Centre (CIC) in January 2017 to advise both the FIRB and the government on potential risks.

It was given broad powers to demand confidential information from operators, including staffing, governance and outsourcing arrangements. In certain circumstances, it can direct operational decisions of infrastructure managers. There is parallel legislation for the telecommunications industry.

The OECD has hailed the CIC as a new evolution in the control of foreign investment globally. It says the first stage was the identification of sensitive sectors where foreign investment was restricted, such as defence or media industries. The second stage was the systematic screening of foreign investment, as practised by CFIUS and FIRB. The third stage, encapsulated by the CIC, is empowering government to intervene in the operations of businesses which are already established in the country.44

The FIRB is also paying much greater attention to businesses that hold customer data files. Several very small transactions involving health care operators have been made subject to highly prescriptive conditions, covering how data is to be stored and accessed, and imposing additional governance requirements. Foreign investors in companies with data holdings have been required to retain a majority of Australian citizen resident directors, with some clearly independent of the investor. At least one must have security clearance, so there is someone on the board with whom the government can have a confidential discussion. FIRB can require security arrangements be audited, with auditors rotated at least every three years.

Strengthened US investment controls

The United States is also responding to the greater urgency of managing Chinese investment with the CFIUS blocking several transactions involving Chinese buyers, mostly in technology sectors. A set of far-reaching amendments to the CFIUS legislation expands its scope to cover not only controlling interests but also minority stakes of at least 25 per cent in sensitive industries and technologies, critical infrastructure or data.

The regulations define critical infrastructure as assets which are so vital to the United States that incapacity or destruction would have a debilitating impact on national security, and include highly detailed lists of exactly what is covered —for example, “gas pipelines in excess of 20 inches in diameter.”

The rules are also precise in identifying data thresholds — it must be sensitive personal data covering at least one million US citizens, not including employees of the company. Genetic data is only covered if it relates to identifiable test results of individuals.

There is less detail on the scope of critical technologies and work is still progressing on the definition of “emerging and foundational” technologies which are critical to national security. However, it will include technologies subject to export controls. There is a list of 27 industry sectors along with 14 different technology categories which would be covered and are included to guide investors.

Australian foreign investment lawyers contrast the specificity of the US regulations with the lack of transparency in the FIRB requirements, which can leave investors and their advisors guessing about the sensitivity of a transaction and the steps they may need to take to mitigate concerns. Australian regulation gives the FIRB absolute discretion to decide what infrastructure or data will be covered.

The close partnership between the United States and Australia on the national security risks posed by foreign investment is shown in their common stance on the participation of Chinese telecommunications company, Huawei, in the next generation of internet infrastructure.

They also commend the 25 per cent threshold in the United States and the fact managed funds are exempted. Australian rules catch minority stakes below 20 per cent.45

The new US regulations explicitly exempt Australia, along with Canada and the United Kingdom, because of the strength of their security ties with the United States, with the regulations referring to the “robust intelligence sharing and defence industrial base integration mechanisms with the United States.”46 The exemption is subject to review in two years and the United States has indicated other nations may also be considered.

The close partnership between the United States and Australia on the national security risks posed by foreign investment is shown in their common stance on the participation of Chinese telecommunications company, Huawei, in the next generation of internet infrastructure. Australia was the first nation to expressly ban Huawei from any role in its 5G network, and the rationale it used has since been repeated by the United States to advocate other nations with which it has a security alliance should also exclude the Chinese company.

The Australian prohibition, announced in August 2018, did not mention Huawei by name but said Australia would exclude vendors who may be subject to directions from a foreign government which conflict with Australian law because of the risk of unauthorised access or interference. This formulation is based on Chinese national intelligence legislation, passed in 2017, which requires organisations and citizens to “support, assist and cooperate with the state intelligence work,” as requested.47 It avoided basing the ban on the suspicion Huawei had inserted undetectable “backdoor” entry points into its networks, as had been widely rumoured but never substantiated.

The OECD argues discriminatory restrictions do result in costs from foregone investment and efficiency gains while conceding a government’s right to regulate in the public interest to achieve policy objectives is paramount.48 Huawei and its advocates have maintained its technology is superior to any rivals and bans will result in inferior internet performance. From the perspective of national security authorities in the United States and Australia, that is a price which must be paid.

The outlook for the relationship

Australia and the United States both prosper from their economic partnership. The AUSFTA provides an anchor to the relations which businesses from each nation have in the other, delivering clarity to their rights which has helped to underwrite bilateral investment and goes far beyond the individual concessions which each side offered on trade during the hard-fought negotiations in 2003 and 2004.

As Richard Harris and Peter Robertson have argued, in the context of a global trade war, the commitment and insurance value of the AUSFTA could be worth as much as 0.5 per cent of Australian GDP per capita.49

The AUSFTA was an innovative agreement, going further in spelling out protections for intellectual property, access to procurement and investment rights than previous trade deals. Importantly, it was embedded in the strategic alliance between the two nations which was forged in the crucible of the Second World War and formalised with the ANZUS alliance in 1951.

The cultural and language affinities contribute to the ease of doing business in each other’s markets, as does the legal framework and the strength of economic institutions from banking, corporate and competition regulators to the central bank and the conduct of economic policy.

Governments on both sides may throw what the Americans would term “curve balls” from time to time, however, business can have a faith the fundamentals of good economics are understood by policymakers in the two nations.

The economic relationship is strong. The United States remains by far Australia’s largest source of foreign investment and destination for Australian investment overseas and is also its third-largest trading partner.

The bilateral flow of direct and portfolio investment strengthens both nations. Direct investment creates production, employment and income. Every firm has its unique talents so direct investment brings a cross-fertilisation of knowledge, management practice and technology. Direct investment is long-lasting and represents a firm commitment by the board and management in one country to the operations in another.

The strength of the relationship between the two nations is of enduring value, but there are challenges demanding policy responses if the prosperity it generates is to continue undiminished.

Portfolio investment brings flexibility to the funding of both business and government improves the dynamism of recipient economies while enabling investors to diversify their risks.

The bilateral flows of both direct and portfolio investment between Australia and the United States have held firm during a period of weakness globally. Trade flows in high value-added goods and services have performed well in both directions.

The strength of the relationship between the two nations is of enduring value, but there are challenges demanding policy responses if the prosperity it generates is to continue undiminished. Global growth in both trade and cross-border investment slowed following the global financial crisis, with most indicators either at a standstill or declining before the pandemic-induced recession began.

Economic nationalism is leading to discriminatory barriers to international commerce. The embrace of globalisation between the 1980s and the 2008-9 financial crisis has given way to a populism that finds an easy target in the foreigner, whether that is an asylum seeker or a multinational corporation.

In a static market, the share of sales is paramount and encourages the pursuit of protectionist policies, although their ultimate result is to suppress sales further. A database of protectionist measures imposed by G20 countries has counted 2,723 new trade distortions covering 40 per cent of world trade in just the last three years.50 Less than a quarter of these measures were imposed by China or the United States which have dominated the headlines with their conflict over trade, technology and strategic intent.

The strongest message in this survey of the economic relationship between Australia and the United States is that Australia should be alert to the risk which its elevated company tax rate and sometimes aggressive stance towards multinational enterprises leads to a reappraisal by US enterprises of the benefits of investing here.

The flow of US investment to Australia has been strong over the past three years but at least part of that flow may reflect US companies maximising tax credits before the United States shifted to a territorial tax system, while another part may be US firms restructuring to meet the demands of Australian tax law changes.

The reality of a tax regime with a high statutory rate and offering relatively few company tax deductions will come into much sharper focus in US boardrooms under its new territorial system for taxing global companies.