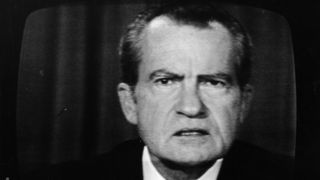

Carl Bernstein, one half of the Woodward and Bernstein journalistic duo from TheWashington Post whose investigations made a significant contribution to the fall of Richard Nixon in 1974, is in no doubt as to where the real Nixon can be found. The “real” Nixon, he argues, is to be heard on the White House tapes, revealing the presidential response to the Watergate burglary and engulfing scandal.

This Nixon assumes the dimensions of a political thug: threatening, bullying, and unrestrained in his criminal proclivities. It is as disturbing as it is unedifying.

But there are other dimensions to the 37th president of the US, as John A. Farrell details in his surprisingly fresh and revealing portrait, Richard Nixon: The Life.

Some of this deeper understanding of Nixon reveals his human weakness, despite the bravado, as perhaps best reflected in his emotional turmoil before and after his so-called Checkers televised address in 1952, which saved his vice-presidential nomination as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s running mate.

It is difficult to approach a new Nixon biography without confronting the immediate questions of what could possibly be said that is original or new. After all, from Woodward and Bernstein’s All the President’s Men or The Final Days to Stephen Ambrose’s comprehensive three-volume biography Nixon, much has been written. And Oliver Stone’s cinematic portrait, Nixon, has been joined by Meryl Streep (Kay Graham) and Tom Hanks (Ben Bradlee) in The Post, another drama on the struggle between the press and presidential power during the Watergate crisis.

Farrell, whose previous biographical subjects have been lawyer Clarence Darrow and former US House of Representatives Speaker Tip O’Neill, has crafted an excellent book, thoughtful in approach, original in research, crisp in prose and definitive in conclusions.

Some of this deeper understanding of Nixon reveals his human weakness, despite the bravado, as perhaps best reflected in his emotional turmoil before and after his so-called Checkers televised address in 1952, which saved his vice-presidential nomination as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s running mate.

Richard Milhous Nixon, from a struggling Quaker family in Whittier, California, returned from war service in the South Pacific to be persuaded to run for congress against the veteran Democrat Jerry Voorhis. This first campaign set the pattern for Nixon’s future, as the “rockin’ sockin’ ” candidate emerged during the red scare that dominated post-war American politics.

Nixon knew his opponent was no communist, but his vicious attacks on Voorhis’s congressional record, his distortions of the congressman’s alleged associations with left-leaning political groups and his savage damning in debates, labelling his opponent a communist “fellow traveller”, carried the day.

Nixon’s campaign was secretly well-funded by the oil industry. And an early capacity for no-holds-barred politics emerged, as Farrell records: “He needed to win, and his plans revealed his hunger, and an incipient susceptibility to intrigue. Set up … spies in V. camp, he wrote.”

The 12th congressional district of Los Angeles County sent Nixon to Washington as its new representative.

The defeat of the hapless Voorhis, and four years later the demolition of Helen Gahagan Douglas, smeared as “the Pink Lady” by Nixon in the contest for a US Senate seat, saw American politics welcome its poster boy for anti-communist crusading, especially on the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The Nixon Presidential Library at Yorba Linda, California, describes his campaigns as “hard”. In reality, the darkest shadow was falling across the American republic since Colonel Aaron Burr (who killed Alexander Hamilton in a notorious duel) was elected vice-president in 1800.

Bill Clinton, probably thinking as much about his own legacy as that of Nixon, argued in his 1994 eulogy for the late president that Nixon was entitled to be judged on his entire career and not just on the Watergate episode.

Farrell certainly affords Nixon this courtesy, but the conclusion is perhaps even more damning for events prior to the 1968 presidential election, in which Nixon defeated his Democratic opponent, Lyndon B. Johnson’s vice-president Hubert Humphrey.

As Theodore White revealed in The Making of the President 1968, in the wake of the brutally divisive Democratic convention in Chicago that year, the party was both broken and broke. Anti-war demonstrators disrupted the stumbling Humphrey campaign until the vice-president broke with LBJ on Vietnam.

Then Johnson, the master politician, produced the “October surprise” and ordered a bombing halt in North Vietnam. Humphrey’s campaign numbers rose; the Democrats rallied; the election narrowed. And the road to a negotiated peace settlement opened. Enter Nixon.

Nixon established a back channel to South Vietnam’s president Nguyen Van Thieu through Anna Chennault, the widow of the wartime commander of the Flying Tigers, Claire Chennault, discouraging participation in talks. Through FBI taps, LBJ knew Nixon’s denials were false and that peace talks were being sabotaged. The opportunity for a peace settlement in 1968 was lost. Tens of thousands more would die in Vietnam.

Farrell’s conclusion is blistering:

Given the lives and human suffering at stake, and the internal discord that was ripping the United States apart, it is hard not to conclude that, of all of Richard Nixon’s actions in a lifetime of politics, this was the most reprehensible.

Nixon’s diplomatic triumphs did change global politics, with the opening to Beijing and detente with Moscow. And after a horrific resumption of bombing, Hanoi did sign a peace agreement.

only Nixon could have been ensnared in the Watergate net. His White House planned the most extensive criminal campaign ever conceived in American politics.

However, it is useful to understand that no Democratic president could ever have embarked on the China initiative. Nixon and the American anti-communist right would have denounced any such move as close to treason. Only Nixon, the virulent anti-communist, could shake hands with Mao Zedong.

And only Nixon could have been ensnared in the Watergate net. His White House planned the most extensive criminal campaign ever conceived in American politics.

His former attorney-general, John Mitchell, authorised it.

Farrell is alert to the possibility that Nixon’s real concern in 1972 was what Larry O’Brien, former lobbyist for Howard Hughes and then chairman of the Democratic National Committee, had in his Watergate office safe about Hughes’s loan to the president’s brother, Donald.

A bungled burglary ultimately destroyed a presidency.

John Dean demonstrated beyond any doubt in The Nixon Defence that Nixon had no credible defence for Watergate at all. The conclusion that needs to be drawn, however, relates to the peril Nixon represented.

Barry Goldwater (Republican, Arizona) delivered a blunt but compelling conclusion: “I don’t think he should ever be forgiven. He came as close to destroying America as any man in that office has ever done.” For now.