On Thursday in the US (Friday morning AEST), for the first time in the 2020 presidential campaign the 10 leading candidates in the Democratic Party will share the same stage.

The frontrunners: Foreign policy and the Democratic Party in 2020

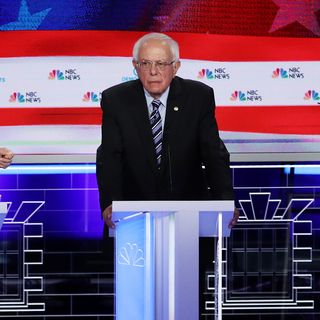

The spectacle will lay bare deep divisions between centrist candidates such as Joe Biden and progressives such as senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, particularly on hot-button issues such as economic inequality, healthcare and climate change. Foreign policy, the area in which US presidents have the greatest capacity to implement their vision, could easily go unmentioned.

The focus on domestic policy in the Democratic primary masks significant shifts on foreign policy. After decades of centrist foreign policy, the Democratic Party’s platform is getting tougher on China and growing more sceptical of the utility of free trade, high defence spending and US leadership in the Middle East.

Though Democratic primaries always feature a pull to the left, the trend now is more pronounced than in recent presidential cycles because of the strength of the party’s progressive wing, which is dragging the party left on almost all foreign and domestic policy issues — except China.

The China hardening is not a Trump-specific or a Republican-only phenomenon. Rather, getting tough on China is a rare example of bipartisan consensus between Donald Trump and Democrats in a highly polarised Washington.

Getting tough on China is a rare example of bipartisan consensus between Donald Trump and Democrats in a highly polarised Washington.

The Democrats’ confrontational tone towards China is consequential for Australia, driven by concerns over economic issues, human rights and geopolitics. They lament job losses because of Beijing’s economic policies and criticise China’s record on intellectual property. The increasingly authoritarian nature of the Chinese Communist Party is an animating issue for Democratic candidates, whose tone on China is becoming more ideological.

Frontrunner Biden has said the US finds itself in “an ideological struggle … a competition of systems (and) values” with China. South Bend, Indiana, mayor Pete Buttigieg has singled out “Chinese techno-authoritarianism”.

A Democratic administration would put pressure on Canberra to stand shoulder to shoulder on highly sensitive issues for the Chinese Communist Party, including Taiwan, Hong Kong and Xinjiang.

US voters across the political spectrum overwhelmingly view China as America’s top competitor. According to recent polling by Pew, only 26 per cent of Americans held a favourable view of China, compared with 60 per cent with an unfavourable view — the highest level since Pew began asking the question in 2005. In line with public opinion, Democrats broadly support Trump’s confrontational approach towards Beijing, though not all his methods.

Yet while Democrats are talking tough, centrists are hesitant and progressives hostile to elements of what strategists consider to be the key planks of competition with China, such as increased defence spending and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Even if a centrist Democrat were elected and wanted to reinvigorate US force posture in the Indo-Pacific, it is unclear that they would ask congress to increase defence spending significantly or would meaningfully shift military assets out of the Middle East in a difficult political and budgetary environment. Leading progressive candidates Warren and Sanders pledge to slash the defence budget and broadly support Trump’s tariffs against China.

As much as there is an emerging bipartisan consensus on China, Democrats have deep emotional differences on Middle East policy.

As much as there is an emerging bipartisan consensus on China, Democrats have deep emotional differences on Middle East policy.

Progressives are coalescing around a different approach to those taken by the Obama or Clinton administrations. The major candidates all support re-entry to the nuclear deal with Iran, though there would be significant hurdles involved, and Democrats differ on the extent to which the deal should be contingent on other issues such as Iran’s ballistic missile program. Israel has become a divisive issue within parts of the party, defined by the differences between older, powerful, pro-Israel members of congress and those who argue the US should reduce its military and political support for Jerusalem.

All plausible Democratic presidents promise immediately to alter the style and much of the substance of Trump’s foreign policy. They mention the need to rebuild strained ties with US allies and partners, and, contrary to Trump’s focus on the military, emphasise the non-military tools of the US’s international engagement, including diplomacy, trade, aid and people-to-people links.

Where Trump often admires authoritarian leaders, the Democratic candidates are critical of authoritarian regimes, including allies such as Saudi Arabia. All pledge to end the “forever wars” in Iraq and Afghanistan and to rejoin the Paris Agreement.

At this stage there are five Democratic frontrunners: Biden, Warren, Sanders, Buttigieg and senator Kamala Harris, who has yet to lay out her foreign policy platform. The outcome of this race is far from clear, but the foreign policy platform of the Democratic Party is shifting, fast, and Australia needs to be paying attention.