Executive summary

In the 2020 Defence Strategic Update, the Coalition government warned that Australia’s region ‘is in the midst of the most consequential strategic realignment since the Second World War.’1 This warning was issued in a context where bilateral tensions with China were building, and doubts had grown among US allies worldwide about the credibility of US alliance commitments under the Trump administration. The commissioning in August 2022 of a Defence Strategic Review by the Albanese Government ‘to ensure Defence has the right capabilities to meet our growing strategic needs’2 confirms that the pessimistic assessments of the 2020 Defence Strategic Update have, if anything, hardened since 2020.

There are strong indications that similar shifts are occurring in the views of Australians at large. Public consultations in advance of the 2016 Defence White Paper revealed that the Australian people felt a profound sense of uncertainty regarding the country’s security situation.3 Indeed, an established trendline in successive polling by the Lowy Institute between 2010 and 2022 has been an increasing feeling of insecurity among Australians, and a significant increase of those seeing a threat from China since 2018.4 Far from abating, in 2022, unease about Australia’s future security in the Indo-Pacific appears to be the new normal.

While there is an active debate among Australia’s expert foreign policy and defence communities about the future of Alliance cooperation, much less is known about the views of Australians who are not professionally engaged in these issues.

As Australia adapts to an altered security landscape, it is more important than ever to look beyond the headlines to understand views and access ideas from across the nation on how strategic policy can and should evolve.

The Alliance with the United States (with a capital ‘A’ as it has become in official government documents) remains the single most important element in Australia’s approach to managing strategic change in the Indo-Pacific. While there is an active debate among Australia’s expert foreign policy and defence communities about the future of Alliance cooperation, much less is known about the views of Australians who are not professionally engaged in these issues.

With that in mind, this project elicited detailed perspectives from Australians drawn from all of the nation’s states and territories through an extensive national consultation process. Over the course of 29 workshops, we spoke to 232 diverse participants in an open discussion that was framed by the following three questions:

- What is the Alliance for, is it important to Australia, and why?

- How can and should Australia leverage the Alliance to navigate the profound security challenges it confronts?

- What should future cooperation with the US look like — or not?

After participation in a 90-minute roundtable discussion, each of the 232 participants were invited to respond to an anonymised survey. A total of 150 respondents, 64.6 per cent of the workshop participants, completed the survey.

The major findings of this report are that:

- Overall, Australians remain positively predisposed towards the Alliance and find it of enduring value. All but a small minority were supportive of the Alliance continuing, even if some argued for substantial change. The results from the workshops and survey of participants align with public polling data from the Lowy Institute, the United States Studies Centre, and Australian Election Study data and analysis.5 That said, the picture is more complex than often portrayed, and views do not fall neatly in pro- or anti-Alliance camps. Most supporters of the Alliance acknowledge that it has shortcomings, while most who are ambivalent about the Alliance concede that it has some advantages.

- Though there is a broad spectrum of views on the Alliance, there are nevertheless four distinct groups among the Australian population:

1. Full Supporters favour close cooperation and even integration of US and Australian defence efforts.

2. Reserved Supporters are the most diverse group. They see benefits of the Alliance, but raise concerns about maintaining a measure of independence and distance to the United States.

3. Sceptics are not convinced that the Alliance, in its current form, is necessarily benefiting Australia’s security and would like to see significant change.

4. Opponents, for a variety of reasons, but often because of their views of the United States, see the very existence of the Alliance as detrimental to Australia’s interests. - Across the 150 survey responses, those who identify the Alliance as a net positive for Australia’s security are by far the largest group, at 69 per cent of respondents. Within these four distinct groups, Reserved Supporters are the largest, at 33 per cent of all respondents. They qualify their support with concern about Australian independence and sovereignty, while 30 per cent of all respondents are Full Supporters voicing no such concerns. Sceptics represent 23 per cent of respondents, and Opponents 8 per cent.

- A transactional mindset underpins most Australians’ approach to the Alliance. Bluntly put, Australians believe that maximum benefits should be extracted from the United States with minimal commitments on Australia’s part, and that greater Australian engagement within the Alliance should lead to identifiable benefits in terms of increased influence, access, or resources from the United States. Even if they disagree on the result, most Australians judge the Alliance through the prism of cost-benefit analysis. Alliance supporters believe that the bedrock of the Alliance is shared interests, rather than shared values, or indeed a sense of shared history.

- There is uncertainty among Australians about what the Alliance is for today, as distinct from what it is against, or what it has been in the past. The perceived lack of a sense of purpose in the Alliance is a common theme. This contrasts with perspectives on other alliances, especially NATO, which has in recent years become more relevant in the context of Russian aggression in Europe. Most Australians are looking for articulation of a positive, more aspirational vision for the Alliance that they can subscribe to, but the phrase ‘rules-based order’ does not resonate.

- Supporters and opponents alike are concerned about the re-emergence of Donald Trump as US President, or someone like Trump, who would disrupt the US global role. Australians believe that stability in the Alliance will be dependent on domestic political developments in the US — including the potential erosion of democracy — rather than anything that may occur in Australia.

- Australians are uncertain about the practical significance of the commitments that the Alliance entails. When Australians think about the scenarios in which Australia and the United States may have to operate as allies, they do so largely with reference to two starkly different situations. First, 1942, when the United States came to Australia’s aid in the Second World War, remains a key reference point for Australians when they think about the fundamental purpose of the Alliance. Not seeing today’s situation in stark terms of national survival, some are therefore sceptical of the value of the Alliance. The second are ‘wars of choice’ in Iraq, Afghanistan and Vietnam, which many Australians view as mistaken attempts to gain influence in Washington that did not relate to the core defensive interests in the Alliance.

- In contrast, hardly any Australians think of the Alliance in terms of the threat scenarios that animate many of today’s policy debates and proposals for closer cooperation in the Alliance, such as countering ‘grey zone’ coercion or attacks on allied forces ‘in the Pacific area’ mentioned in the ANZUS Treaty. Even the many Australians who see a deteriorating security environment, and are thus not indisposed towards closer cooperation with the United States, are unsure how the ANZUS Treaty will assist Australia in managing such scenarios.

- Many Australians believe that the Alliance needs to be extended to encompass deeper cooperation beyond the traditional defence context, particularly to address climate security. Australians recognise the close trust and effective cooperation in the Alliance but see defence cooperation as part of a more holistic relationship. Australians expect the Alliance to deliver on what they see as the main challenges facing Australia and the world; many do not see sufficient energy applied to cooperation with respect to crucial non-defence challenges. In that sense, the Alliance is, for many Australians, an incomplete project.

- Most Australians are positively disposed towards the Alliance but are not sure what it means for Australia’s sovereignty and its capacity to make independent decisions. This remains a concern for many, even if they place significant trust in the US and seek closer military cooperation to safeguard Australia’s security. Concerns about the Alliance in this regard are often expressed as general feelings rather than in relation to specific issues or examples. That said, except among opponents, the wars in Iraq and Vietnam are seen as the past, and even in these situations blame is placed on Australian governments as much as the Alliance itself. Few Australians voice unprompted concern about the presence of US forces in Australia, but the term ‘bases’ evokes generally negative connotations. In that sense, concern with sovereignty and independence are not necessarily about the Alliance itself, but about Australia’s ability to manage its own interests.

- Whether they strongly support or oppose the Alliance, Australians think that relations with the immediate region are a crucial consideration — and generally, they see a need for Australian governments to attach greater priority to this. Many opponents think that the Alliance is holding Australia back from building genuinely cooperative relationships with its neighbours. Most respondents believe that Australia has not built the close regional relationships that it could have, and is therefore under-delivering in the Alliance, including in the Southwest Pacific. In this context, Australia’s concept of its neighbourhood is very much informed by geographic proximity: Southeast Asia and the South Pacific are what Australians are thinking about, more than Indo-Pacific partners such as India, Japan, or South Korea.

The relevance and future of the US alliance

Australia is no stranger to strategic disruption. Throughout the 20th century and for the first two decades of the 21st century, successive Australian governments responded to changes in the global and regional balance, as first decolonisation and then the economic rise of many Indo-Pacific countries transformed the strategic environment. Australia has focused primarily on the Indo-Pacific, but since 1945 it has also been deeply engaged with international institutions and played a proactive role as an influential middle power on issues including arms control, the environment, and human rights.

Once implemented in full, the AUKUS agreement envisages integrating Australian defence capability with that of its US ally to an unprecedented extent which will likely increase expectations of growing Australian future contributions to the Alliance.

In all of this, the relationship with the United States has been central to Australia’s capacity to adapt to strategic change. Even as defence ‘self-reliance’ became a bipartisan and deeply ingrained Australian policy in the 1970s, it was both enabled by, and seen as a major contribution to, the Alliance with the United States. At the same time, Australia’s participation in US-led wars in Vietnam and later the Middle East, as well as its contribution to US nuclear strategy by hosting the Joint Facilities, made Australia’s management of the Alliance politically controversial.

Today there is a growing consensus among analysts that ‘after nearly 75 years as the region’s pre-eminent military power, the US can no longer guarantee a favourable balance of power in the Indo-Pacific by itself.’6 Since 2012, Australian governments have been willing to increase military cooperation with the United States through the ‘Force Posture Initiative,’ under which the now routine, rotational presence of US Marines training in the Northern Territory is the most visible part.

The deep networks that exist between Canberra and Washington in defence and intelligence have been reinforced by the AUKUS agreement, which has keyed Australia into the US (and UK) nuclear submarine program while promising substantial military technology sharing, including in the critical domains of undersea warfare, hypersonics, quantum computing and artificial intelligence.7 Once implemented in full, the AUKUS agreement envisages integrating Australian defence capability with that of its US ally to an unprecedented extent which will likely increase expectations of growing Australian future contributions to the Alliance. Washington is already on the record as noting that it anticipates Australia will play a greater role in future regional military operations as a consequence of AUKUS.8

Some commentators, however, have also called for Australia to lobby Washington to disavow the pursuit of primacy in the Indo-Pacific and accommodate Beijing to avoid a US-China war.9 Others maintain that Australia will be best served in the long-term by supporting US efforts to actively counter Chinese efforts to challenge US influence in the region by reasserting traditional alliances and building on new initiatives such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the ‘Quad’) and AUKUS in order to maintain a favourable balance of power in the region that supports Australian and US interests.10

Public opinion on the US alliance

But what are the views of non-expert Australians on the future of the Alliance? This is an important — but often overlooked — question for policymakers. Though deliberations by experts located overwhelmingly in the ‘Canberra bubble’ dominate the national discourse over strategic policy, given the specialised nature of the field, what non-experts think about Australia’s strategic policy matters for at least three reasons.

The first relates to the need for democratic governments to be aware of what non-elite constituencies are thinking in relation to policy areas, not just specific policy issues. Long gone are the days when foreign and defence policy was ‘best left to the experts’ and essentially quarantined from democratic debate. This was demonstrated starkly during the 2022 Australian Federal election, when foreign policy and strategic issues took centre stage with the announcement of a security pact between China and the Solomon Islands.11 On most, if not all, areas of public policy, governments risk making decisions that do not enjoy support among the population. Gaining majority public support for specific decisions is not in itself a pre-requisite for governing successfully — if it were, governments would be relentlessly populist. Nevertheless, if governments are to achieve legitimacy in key areas of public policy (including strategic policy), a degree of national consensus is required.12 This means addressing — and in some cases pre-empting — challenges that threaten to undermine that consensus, either in the short term or long term.

The second reason is that while public polling data has for some time reflected consistently strong support for the Alliance — indeed the 2022 Australian Election Study data shows that 48 per cent of respondents see the Alliance as ‘very important’ to Australia compared to 39 per cent in 201913 there are also hints at some complex views hidden in recent opinion polling. Polling commissioned by the United States Studies Centre shows that despite strong support for the Alliance, 76 per cent of voters believe that Australia should develop a foreign policy independent of the global powers, and 82 per cent believe that Australia should ‘stand up’ to China.14 The 2022 poll by the Lowy Institute revealed that ‘warmth and trust in the US have not returned to the high levels that were recorded in the Obama years.’15 While 87 per cent of respondents (the highest since the Lowy poll began in 2007) believed the Alliance was ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ important for Australia’s security, 77 per cent of the same respondents agree with the statement that ‘Australia’s Alliance with the US makes it more likely Australia will be drawn into a war in Asia that would not be in Australia’s interest.’ And while the proportion of Australians in Lowy’s poll who consider it very or somewhat likely that China will become a military threat to Australia in the next 20 years has risen from 44 per cent in 2011 to 75 per cent in 2022, the increase of those in favour of allowing US forces to be based in Australia is far smaller, from 55 per cent (2011) to 63 per cent (2022).

The third reason relates to the need to generate fresh ideas about Australia’s management of the Alliance in the third decade of the 21st century. Though voices have emerged in the national discourse on the Alliance in recent years, most of the views that gain prominence tend to fall into ‘pro’ or ‘anti’ Alliance camps. The polarising dynamic of social media, though helping some new perspectives gain traction, has reinforced binary, and often simplistic, interpretations of the Alliance. Tapping into the views of those from outside the circle of experts — both for and against the Alliance — who routinely feature in national discourse encourages fresh ideas about how the Alliance with the US can be better managed by Australia in the future.

Project research design

Long-standing and robust quantitative polls of Australian public opinion, of which the Lowy and United States Studies Centre polls are leading examples, are important sources on how Australians view international issues. Quantitative research prioritises systematic large-scale random sampling techniques to gain statistically significant results on set questions, but by their nature they are inevitably limited in their capacity to uncover nuanced views.16 Instead, this project was based on an extended, qualitative consultation process. Qualitative research of this type uses small samples in much greater depth, tends to be more explorative in approach, and focuses on specific processes, cases, and context to examine causality.17

The centrepiece of this project was a broad process of national consultation that engaged a wide variety of Australians in structured dialogue to address the project questions.

The centrepiece of this project was a broad process of national consultation that engaged a wide variety of Australians in structured dialogue to address the project questions. From February to August 2022, the project team undertook face-to-face consultations with 232 individuals drawn from wide-ranging backgrounds in every State and Territory capital city, with a mix of in-person and online formats. The research team was conscious of ensuring diversity of representation and addressed this through targeted recruitment strategies and promoting accessibility of workshops in-person (across a variety of locations) and online.

A survey was also made available to those who were consulted. The survey elicited 150 written responses and was designed as a quality assurance mechanism to ensure that those who were in the consultation sessions had the opportunity to provide comments via a different medium. By the end of the consultation sessions, saturation had been reached whereby the same themes kept emerging and there was sufficient information to replicate the study results between the session discussions.18 Both the survey questions as well as the demographic breakdown of the 150 survey participants is available in the appendices.

To capture views not generally engaged in debates about the Alliance, participants were recruited by contacting industry bodies, civil society groups, think tanks that do not focus on international security issues, and public sector organisations (including universities). Participant involvement was self-selecting and did not entail any incentive payments — monetary or otherwise. Once registered for a consultation workshop, participants were sent a detailed background paper prepared by the project team that incorporated a history of the Alliance, recent developments, and the questions to be covered in the consultation session. Appendix 1 includes the background paper that was shared with participants.

Facilitated by the project team members, consultation workshops were not recorded. Ethics approval was obtained through the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee, and participants were sent an information and consent form prior to the workshop. All discussions were conducted according to the Chatham House rule — i.e. no view expressed would be identifiable to an individual participant upon collation and reporting of the data. Participants were informed prior to each session that the project was funded by the Australian Department of Defence and that the report would be made public after the project was completed.

Each of the 29 consultation workshops ran for approximately 90 minutes, and the project team took extensive notes, which were supplemented by the survey noted above. At the end of each session, the project team invited questions from those in attendance. These questions often ranged across aspects of the project, including its research design and planned dissemination of results. Participants were informed that they were welcome to email the project team with subsequent feedback or questions after the consultation session.

Project findings

1. Australians support the Alliance, but often their views are not clear-cut

Overall, Australians remain positively predisposed towards the Alliance and find it of enduring value. All but a small minority were supportive of the Alliance continuing, even if some argued for substantial change. The results from the workshops and survey of participants align with the broader public polling data that consistently show high levels of support for the Alliance.

But the picture is more complex than often portrayed, and views do not fall neatly within pro- or anti-Alliance camps. Most supporters of the Alliance acknowledge that it has shortcomings, while most who are ambivalent about the Alliance concede that it has some advantages. Those in the latter category tend to portray the Alliance as a necessary evil in a dangerous world:

‘I would love to see Australia as a neutral country but that would be impossible. We are in alignment with the US but we need an iron-clad guarantee that they will support us in the event of an attack.’

Another participant observed that:

‘Once upon a time we were the lucky country — but now no longer. Close proximity to China, higher risk of being attacked, and we need a military presence. What are we trying to achieve with the Alliance?’

Most supporters of the Alliance struck a similarly moderate tone:

‘We need the Alliance, it’s just how we go about it and how we project it. Once we advance in areas like Pine Gap, we put a target on our back, so we have to be careful of that. Think about China’s advancement in the South China Sea and consider whether it’s defensive or offensive.’

Seen in this light, Australians as a whole seem open-minded about the Alliance and the benefits it yields. Very few Australians have a narrow, unconditional perspective on the Alliance:

‘Australia should continue its cooperation with the US positively on upholding security and stability in the Indo-Pacific, which builds up our long-term strategies and mutual benefits. We need to promote our unshakeable support to our allies in Southeast Asia in the name of supporting democratic alliances and increase Australia’s role globally. However, Australia should also avoid a large number of NATO troops intake to the mainland and the construction of nuclear stations, which would trigger the tensions in neighbouring countries. We should fight against the Cold War mentality and seek international cooperation.’

Supporters of the Alliance have also reflected on the Alliance as a safeguard against the potential security challenges that Australia could face by itself:

‘A historic alliance (expressed/ formalised by ANZUS/AUKUS or more generally) that is still relevant, especially if one takes a realpolitik view of the world and not one based upon dreams of what we would like it to be. The world is a competitive place (physically and economically). Despite peoples’ best wishes, not everyone thinks the same as we do and regrettably, they also force their will/actions on others. To avoid such situations people/countries need to be willing to stand up for themselves. Coupled with this is the need to recognise that Australia, while a rich, ‘middle power,’ is not currently in a position to do this independent of others. Reliance on alliances with like-minded countries/peoples such as the USA is key here.’

Comments among opponents of the Alliance raised concerns that, while there are merits to the Alliance on paper, the costs and commitments under the Alliance outweigh these in practice:

‘The alliance is, from Australia’s point of view, aimed at protecting our interests. In reality it has led us into unsuccessful and aggressive wars of choice aimed at strengthening US hegemony. It is an unequal alliance.’

2. Australians’ views of the Alliance fall into four broad groups

While there is a broad spectrum of views rather than clear camps on the Alliance, there are four distinct groups amongst the Australian population: Full Supporters favour close cooperation and even integration of US and Australian defence efforts. Reserved Supporters are the most diverse group. They see the Alliance as beneficial, but voice concerns about maintaining a degree of independence and distance from the United States. Sceptics are not convinced that the Alliance, in its current form, is benefiting Australia’s security. Opponents, for a variety of reasons, but often because of their views of the United States, see the very existence of the Alliance as detrimental to Australia’s interests.

The project used the survey to quantify the size of these groups, within the limits of the study parameters. Groups were identified based on whether they saw the Alliance as unambiguously increasing security and arguing for new, expanded or closer cooperation (Supporters), were clearly conflicted or ambiguous on the benefits of the Alliance (Sceptics), or clearly saw it as a net negative (Opponents). In addition, the responses were categorised according to whether they voiced concern about sovereignty or the ability for Australia to make independent decisions, regardless of their view of the Alliance as a whole. This parameter was only useful to further differentiate within the group of supporters between Full Supporters, arguing for closer cooperation without voicing concerns for sovereignty, and Reserved Supporters who do. Sceptics and Opponents generally all included concerns about sovereignty and independence among their reservations about the Alliance, at least in its current form.

Across the survey responses, supporters who identify the Alliance as a net positive for Australia’s security are by far the largest group, at 69 per cent of respondents.

Across the survey responses, supporters who identify the Alliance as a net positive for Australia’s security are by far the largest group, at 69 per cent of respondents. While our methodology is different, this is consistent with a finding in the Lowy poll in 2022 that 64 per cent of Australians think the Alliance makes Australia safer from attack or pressure by China. Among the supporters and in general, Reserved Supporters are the largest group at 33 per cent of all respondents and qualify their support with concern about Australian independence and sovereignty, while 30 per cent of all respondents are Full Supporters voicing no such concerns while arguing for closer integration of some form. Sceptics represented 23 per cent of respondents, and Opponents eight per cent. Given the limited sample size and sample selection approach, the only significant demographic difference between these groups was that opponents were overwhelmingly drawn from participants who were from older generations and Australian-born.

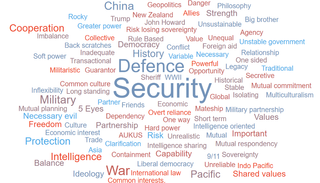

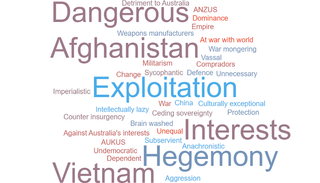

All respondents in the survey were asked to provide the five words that first came to mind when thinking about the Alliance, which further illustrates differences, but also significant commonalities across these groups. For both Full and Reserved Supporters, ‘security’ and ‘defence’ are the most frequently mentioned terms, ‘values’ being a (distant) third for strong supporters only, and even less for other groups. Association with ‘war’ appears in third place among Reserved Supporters and is the most prominent term amongst Sceptics and Opponents, likely indicating the importance of controversial overseas military operations underpinning their views. ‘Dependence’ is a prominent, albeit third-placed term amongst Sceptics.

‘The US-AUS alliance is a strategic partnership between the two nations that has been forged in order to promote liberal democracy and to maintain security overall. It is important because it looks into how to tackle a number of different relevant current issues globally. It is also important not only for security issues but also for the well-being of the two countries’ citizens which in turn enjoy benefits from such an alliance and good political relationship.’

‘The Alliance confirms Australia’s mutual status with the US as a liberal democracy of European descent. It provides assurance to our existence in the region, and connects us to a broader, international front of countries with commitments to free speech and free economics. It does, however, limit our right to free determination, and does commit us to policy directives that may not be within our national interest.’

‘The Alliance is a security-based alliance between Australia and the United States. It is important for Australia, but it also highlights the need for Australia to better develop its own independent foreign policy. Australia has become a vassal state for the United States hosting bases across the north and the northwest. In a multipolar world, Australia has chosen the declining superpower to hang onto through the coming storm.’

‘Australia’s Alliance with the US is an unequal relationship. It serves only US interests politically, economically, militarily, and culturally. It is not a good defence policy for Australia. It has led us into endless and disastrous wars which achieved nothing but enormous profits for US arms manufacturers. Australia should withdraw from the Alliance, close down US military and intelligence bases and attempt a genuine sovereign self defence policy.’

Figure 1. Visual representation of Full Supporters’ associations with the Alliance

Figure 2. Visual representation of Reserved Supporters’ associations with the Alliance

Figure 3. Visual representation of Sceptics’ associations with the Alliance

Figure 4. Visual representation of Opponents’ associations with the Alliance

3. Many Australians believe that the Alliance needs to be extended to encompass deeper cooperation on non-traditional security threats, particularly climate action

This perspective reflects a view that the Alliance, as it currently stands, is narrowly limited to defence matters and must adapt to evolving challenges that go beyond state-based military threats. Australians recognise the close trust and effective cooperation in the Alliance but see defence cooperation as part of a broader relationship. There is a sense in which Australians expect the Alliance to deliver on what they see as the main challenges facing Australia and the world; many do not see the same energy applied to cooperation with respect to pressing non-defence challenges. In this respect, the Alliance is, for many Australians, an incomplete project:

‘There is an opportunity for Australia to use the Alliance for climate change and elaborate on how we define security. I think there’s a shared interest in climate policy and climate security and bringing that into AUKUS. There’s an opportunity to tie that more closely to the Alliance.’

Conceiving the Alliance more in terms of the broader Australia-US relationship, not just the defence dimension, was a strong theme underlying this view. This relates to the broader point expressed by participants that the Alliance will need to adapt to new and emerging challenges if it is to remain relevant in the 21st century. As one participant put it:

‘The Alliance is considered unbreakable so we should see how far it can be stretched.’

There was an associated view that Australia could — and should — be more aspirational in exploiting the Alliance with the US:

‘We need to assert our views for there to be any leverage. We should strengthen our relationship with our neighbours and provide further aid in the region. If we could work with the US on climate change that would be a huge success.’

In a similar vein, another participant observed that:

‘Climate change is increasingly recognised as our greatest threat, and a magnifier of other threats. This is a great opportunity to use the US Alliance to enhance each other’s efforts in radically reducing emissions.’

4. Australians place strong emphasis on the transactional nature of the Alliance

A transactional mindset underpins the way most Australians across the whole of the spectrum approach the Alliance. Bluntly put, Australians believe that maximum benefits should be extracted from the US with minimal input on Australia’s part, and that greater Australian engagement within the Alliance should lead to identifiable benefits in terms of influence, access, or resources from the United States. Even if they disagree on whether it is a good or bad policy for Australia, most Australians judge the Alliance through the prism of cost-benefit analysis.

Supporters of the Alliance believe that Australia possesses the means to exert leverage over the US to pursue its national objectives. But there is some uncertainty over what exactly the source of that leverage is:

‘Australians don’t generally know what Australia can contribute to the Alliance, so that channel of communication needs to be opened.’

With specific reference to leverage, one participant commented that:

‘We do have more influence than we think, sometimes. I think our location will always matter and our intelligence of the region is a potential strength, as are our relationships in the region. We are valuable because we are embedded in Asia.’

There is limited evidence that Australians believe that Alliance interests are fused by shared values, or indeed a sense of shared history, on either side of the Alliance. One contributor observed that:

‘Purpose and goals [of the Alliance] need to be more specific. We need to avoid loose language around “shared values” — identifying what they actually are. Highlighting hard principles — trade, movement, interests, etc.’

This perspective is noteworthy because it strikes a discordant note when compared to narratives from government elites in Canberra and Washington that highlight shared values underpinned by ‘100 years of mateship.’ Australians remain highly sceptical of this rhetorical construct.

Even those Australians who are generally supportive of the Alliance, are quick to identify cultural gaps with the US. As one participant noted:

‘We obviously have a great relationship with the US, and even though we share several liberal and democratic values with the US, we don’t share all of the same values as the US (particularly with gun laws, with their abuse of powers with freedom of speech laws).’

5. Australians are uncertain about the practical significance of commitments in the Alliance, and struggle to conceive of scenarios in which Australia might come under attack

Paradoxically, while Australians are generally not concerned about the credibility of US Alliance commitments per se — extended deterrence questions barely featured in the consultations — it is equally the case that very few have a clear grasp of what ‘security guarantee’ exists in practice in the Alliance. Many are aware of the historical significance of the ANZUS Treaty but remain unsure of its relevance today, and refer to other agreements — including AUKUS — they believe have superseded ANZUS. As one supporter of the Alliance observed:

‘If you look at our defence policy, it’s based on ANZUS that is relatively limited. It isn’t institutionalised. There are too many elements of it that are based on “should” imperatives. Shaping our defence policy on a treaty that was written decades ago is concerning.’

For some, the ANZUS Treaty itself is seen as something of a relic from a bygone era:

‘The Alliance is a product of its time… it doesn’t have the same clarity as NATO — because it has been around for so long and because it has been sentimentalised, the lines have been blurred. People see it more as our relationship with the US as a whole rather than an Alliance.’

When Australians are thinking about the situations in which Australia and the United States may have to operate as allies, they are doing so largely in terms of two, starkly different situations. First, 1942, when the United States came to Australia’s aid in the Second World War, remains a key reference point for Australians when they conceptualise the fundamental purpose of the Alliance, even if they do not see today’s situation in stark terms of national survival and are otherwise sceptical of the value of the Alliance. The second are ‘wars of choice’ in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Vietnam, which for many were mistaken attempts to gain further influence with Washington that did not relate to the core defensive purpose of the Alliance.

In contrast, there was little evidence of widespread concern regarding another prominent Alliance dynamic — apprehension over potential abandonment, which is also a major feature of Australia’s domestic narrative regarding the Alliance going back to the 1950s. Indeed, a landmark book on Australian foreign policy since the Second World War is titled Fear of Abandonment.19

In part, this may be because only few Australians are thinking about the Alliance in terms of the threat scenarios that animate many of today’s policy debates and proposals for closer cooperation in the Alliance, such as countering ‘grey zone’ coercion (which features in discourse regarding China) or attacks on allied forces ‘in the Pacific area’ mentioned in the ANZUS Treaty.

Even the many Australians who see a deteriorating security environment, and are thus not opposed to closer cooperation with the United States, are often vague about how the latter will assist Australia in managing the former, or don’t actually refer to the commitment to come to each other’s aid as the key value of the Alliance:

‘The alliance is for protection, information sharing, reinforcing world order, and presenting a shared front against China amongst many other reasons. Despite the critiques discussed in the session today, I think it is important to recognise the benefits of such a powerful relationship and how much this relationship does provide for Australia in regard to information, technology, militarily, diplomatically amongst other benefits.’

Another participant observed that:

‘I believe the alliance provides a strong commitment to Australia’s security. It makes Australia one of the closest allies to the US. It builds on the fact that Australia and the US are both liberal democracies. It is critically important because the US is seen as the strongest military power in the world. Some have doubts whether the commitment will be met when Australia comes into military conflict. However, the perception of Australia being in this alliance has already created an impact on how other countries treat Australia.’

6. Most Australians are positively disposed towards the Alliance, but are not sure what it means for Australia’s sovereignty and its capacity to make independent decisions

This remains a concern for many even if they place significant trust in the US and seek closer military cooperation as a way to safeguard Australia’s security. Concerns about the Alliance in this regard are often expressed as general feelings rather than pinpointing specific issues.

Fear of entrapment features prominently, particularly with respect to the AUKUS agreement and how Australian support for US military operations against China might be taken for granted because of Australia’s intimate cooperation with the US on nuclear submarines and other cutting-edge military technology. As one participant commented:

‘What worries me with AUKUS is that we can find ourselves at war by default — we could find ourselves in war without much input from our government — entrapment. A bad relationship.’

Another participant observed:

‘I think that the US presence is a double-edged sword. It’s a reaffirmation to the region that the US has our back, but it pins a target on us.’

For Opponents of the Alliance these views tend to reflect long-established concerns.

‘[There is] no benefit in the US Alliance for us. The benefit goes to the US. The US treats us as a client state. Australia wouldn’t be able to escape a potential war with China. Pine Gap is a one-way street and disadvantage for us, making us a nuclear target all for the benefit of the US.’

More recent US-Australian force posture initiatives have further provoked concerns from this group:

‘We have US forces through Darwin — we need to know what they are doing so we maintain our own freedom of action. If we have US assets and troops on Australian soil, we need to know what they are doing. And how do we say no if what they are doing is of concern?’

That said, concern with sovereignty and independence are not necessarily about the Alliance itself, but about Australia’s own ability to manage and look after its own interests:

‘The Alliance in its current form is Australia holding on to its outdated foreign policy strategy of having a “larger powerful nation” to cling on to in the threat of foreign invasion and attack. A relationship with the United States is important for Australia, however, it should not be a heliocentric cooperation that excludes other nations within the Asia-Pacific region from the discussion.’

‘The alliance is critical to understanding how Australian governments behave in the world. It has, historically, reassured white Australian governments that they are not alone in the world — and it still functions that way, often reinforcing the racism behind it (for e.g. through enthusiastic revival of the “Anglosphere”). When it functions well, the alliance grants Australia great leverage as a middle power to work with (and sometimes against) American interests.’

Reluctant supporters — who underscored the imperative of exploiting an Alliance with a great power — also place a premium in Australia retaining maximum sovereignty in the same Alliance:

‘An overarching principle would be sovereignty. In continuing the mutual defence commitment with the US, Australia should safeguard itself as a sovereign country that has the ability to make independent decisions. Any military arrangements (e.g. US military aid or presence in the region) should be not seen to create an obligation for Australia to sacrifice what Australia sees as its national interest — trade or otherwise. Under this principle, I welcome closer military collaboration that can advance Australia’s defence capability.’

Another participant observed:

‘I don’t know that we need more distance [from the US], but we need more independence. We can be happily close allies, but we need to be able to have a level of independence that we haven’t shown in a long time. So the question is: what might that look like?’

Few Australians voice unprompted concern about the presence of US forces in Australia, but the term ‘bases’ evokes generally negative connotations. Australians seem more accepting of a temporary presence of US forces, even if on a semi-permanent basis, than formal arrangements. One participant noted that:

‘I like the idea of having more involvement defence-wise with the US, but I am reluctant to see more military bases here permanently — the more [we] allow them to be here in Australia, we become more reliant on the US, placing less resources and emphasis on our own military.’

It is worth noting that there was negligible support expressed for the deployment of US long-range missiles or nuclear weapons on Australian territory.

7. There remains a sense of uncertainty among Australians about what the alliance is for today, as distinct from what it is against or what it has been in the past

Shared commitment to a ‘rules-based order,’ which has been a recurring theme in government policy statements over recent years, does not resonate among Australians who are keenly aware of the epochal changes in our strategic environment, but who are also unclear about what positive vision the Alliance seeks to advance. The notion of a ‘rules-based order’ is seen as abstract, academic even, and as constituting insufficient foundation for sustaining the Alliance over the longer term. Indeed, for some, the Alliance could well prove a hindrance to maintaining stability in Australia’s own region:

‘If we are going to tackle the China issue, we need to do it in a way that is sophisticated and isn’t just blindly following the US lead, but through things like the Quad and ASEAN and other like-minded Asian countries to maintain the liberal-based order in the region.’

Sceptics are often looking for greater progress on climate change and nuclear disarmament, but most participants are looking for articulation of a positive, more aspirational vision that Australians can subscribe to:

‘Australia could (like NZ) and should be a clear-headed, independent-thinking friend and shape our cooperation with the US towards peace as a positive goal – the nurture of life, human and the planet’s. Thus the emphasis should shift away from military build-up and towards cooperatively addressing our greatest threats – the climate crisis and nuclear weapons.’

Another participant observed:

‘Australia needs to be sensitive to the concerns and anxieties in the Pacific islands region regarding nuclear issues — and needs to ensure its full commitment to the Treaty of Rarotonga. The Alliance needs to be repurposed to address real security threats rather than imagined ones — most significantly the impacts of climate change.’

‘There is a real opportunity now to expand thinking around the alliance beyond binary questions of security and defence, to position Australia as an active peace-builder rather than a reactionary force. Climate action, and leveraging the alliance to pursue it, is central to that.’

Another participant observed:

‘The United States and Australia should use the alliance coordination mechanisms and security and economic dialogues to establish sustainable and secure global supply chains which protect mutual economic interests and ensure that the two countries as well as their partners and allies in the Pacific remain free from coercion, intimidation, and retaliatory economic measures such as tariffs and embargoes by China. Washington and Canberra can also fill a vital gap by electrifying the Pacific and responding to green energy needs as Pacific Island and SE Asian nations have dire needs in light of the increasingly threatening climate crisis.’

Uncertainty or unease with the objectives of the Alliance are also fed by a sense that there is a distinct, perhaps deliberate lack of public information provided by government on the Alliance:

‘AUKUS was simply announced to us. Certainly that should go to parliament. There being no public consultation or conversation is worrying.’

8. Supporters and opponents alike are concerned about the re-emergence of Donald Trump, or someone like Trump, as US president who will have a disruptive impact on the role of the US in the world

This concern articulates closely with evident apprehension surrounding future US reliability. A salient theme among the different groups was that, despite shared democratic traditions, US societal values on issues such as reproductive health and gun control are alien to Australia.

‘If you get Trump 2.0 stepping in, there’s an added risk — do we want to be so reliant on a country that goes down that path?’

More generally, there were concerns expressed about the future stability of the US domestic system itself. The impact of the 6 January 2021 Capitol riots in Washington influenced perceptions of the growing instability in the US political system — which was juxtaposed with Australia’s democratic stability — going forward. One participant noted that:

‘The US-Australian Alliance must be recalibrated as [the] US is going through its own domestic turmoil/struggles.’

Another commented that:

‘Our government has approached the relationship [with the US] with a degree of naivety and hasn’t fully considered US democratic collapse.’

These concerns about the future domestic stability and orientation of the United States were present amongst Supporters as well as Sceptics and Opponents of the Alliance. Some saw a need for Australia as an ally to engage the US on these issues:

‘Australia needs to be a more assertive ally, particularly as the US is changing domestically. We should use our role as a critical friend of the US to remind the US of what it purportedly stands for and how far it may be drifting from that ideal.’

Another participant observed:

‘We need to try and talk them off the ledge. These are the people who invented the Marshall Plan, rebuilt Germany and Japan and boosted their own economy. How does one reconcile this with the clusterf**k that was IRAQ after GW declared victory. Something has gone badly wrong in the US. We somehow need to help them, and help ourselves, rediscover the principles on which the west fought WW2.’

9. Whether they strongly support or oppose the Alliance, Australians think that relations with our own immediate region are a crucial consideration

Generally, Australians want governments to attach greater priority to deeper engagement with our immediate region. Many Opponents think that the Alliance is holding us back from building genuinely cooperative relationships with our neighbours. A majority of respondents share the view that Australia has not built the close regional relationships it could have, and that it is under-delivering in the Alliance, including in the Southwest Pacific.

‘Australia can and should also be using its position as a “close US ally” to foster closer ties with ASEAN members such as Indonesia and regional allies such as Japan and India.’

Another participant observed:

‘Australia should value more highly the “eyes and ears” its provides [the] USA in this region and use that to extract greater economic and military support and investment.’

In this context, Australians’ concept of neighbourhood is informed by geographic proximity: Southeast Asia and the South Pacific are what Australians are mostly thinking about, more than ‘distant’ Indo-Pacific partners such as India, Japan or South Korea.

Sceptics and Opponents believe that Australia’s so-called ‘deputy sheriff’ role has degraded its ability to forge independent relationships with countries in Southeast Asia in particular:

‘Australia is part of the Southeast Asia community geographically. We sometimes seem to forget that. We talk to Southeast Asian countries as if we aren’t part of it but recognising our place as part of that culture and I think the US should respect that.’

Others emphasise the opportunity for Australia to more effectively leverage US networks in the Indo-Pacific to promote national interests independent from the Alliance. Some believe that Australia should be looking to operate more independently from the Alliance in pursuing its objectives in the region, which includes balancing China’s influence:

‘We should pivot ourselves to the region...[but] I do worry that our value is just being a white country in an Asian world. We should work with other regional powers on containment, without having to look toward older European allies that no longer play a major part in the region. I think that a pivot to ASEAN is underplayed in the importance of Australia’s foreign relations.’

The Middle East was barely mentioned. At least in part, this likely reflects the context in which the project consultations were undertaken: the US-led withdrawal from Afghanistan took place in September 2021 and there was widespread publicity in popular media about growing Chinese influence in the Southwest Pacific and perceived Australian (and US) missteps. There was, moreover, a strong theme that Australia’s strategic interests have moved squarely back into the Indo-Pacific after two decades of post-9/11 military engagement in the Middle East.

Insights and policy recommendations

This project has revealed important insights into Australians’ views of the Alliance. While there remains opposition to the Alliance in some quarters and scepticism about its effectiveness, our research showed that Australians overall remain very supportive of the strategic partnership. This support, however, comes with some key caveats: the Alliance is seen as incomplete in that it deals with narrowly defined defence and strategic issues; concerns persist about Australia’s sovereignty and capacity for independent decision making; and there is a view that the Alliance is insufficiently geared towards addressing challenges in Australia’s immediate region. Against this backdrop, we make the following policy recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Define what the Alliance is for, not just what it is against

Given the rapidly evolving strategic circumstances that Australia faces, the Australian government must devote greater attention to articulating the contemporary role of the Alliance and explaining why it is important for Australia. Australians grasp the risks in the modern-day Indo-Pacific, and the Alliance is seen as important, but our research has shown that the perceived benefits of the Alliance in a new strategic era are not clear. Critical to this approach is outlining that the Alliance is a strategic option that Australia actively pursues because of the benefits it brings to Australia and to our region: it is a choice that Australian governments make as part of an independent foreign policy.

Currently, however, there is a sense that successive governments have failed to articulate the Alliance’s value proposition sufficiently to the Australian public, and many do not have strong confidence in Australia’s own ability to successfully manage the trade-offs involved from closer cooperation with the United States. The most substantive statements on the Alliance by senior Australian policymakers in recent years have been made during official visits to Washington.20 Many Australians in the consultations brought up what they saw as the surprising, and under-explained, announcement of the AUKUS initiative.

An annual Ministerial statement to Parliament on the Alliance will not address this deficit on its own, but if the statement responded to these concerns, it would be a good start. This statement should embed the Alliance as part of a positive vision of what Australia and the United States jointly seek to achieve through cooperation — it needs to be for something as part of a better future, rather than defined in opposition, or through history alone. Given the widespread concern with Australian sovereignty, the statement needs to articulate clearly Australia’s role and choices within the Alliance, rather than assume that shared values and interests are a given.

Recommendation 2: Activate a broader-based Alliance

The Australian government needs to devote greater attention — by itself and in partnership with US counterparts — to injecting greater substance into the non-security side of the Alliance. Most significantly, this includes deeper collaboration on climate action, but it also encompasses areas such as economic engagement and investment, and people-to-people links. This is not to deny the central importance for Australia of Alliance military cooperation. However, it is clear, especially among younger Australians, that views of the value of the Alliance are tainted by a perception that it does not respond to the defining challenges of their time, which go beyond defence.

Australians have a strong affinity with the US. The relationship has a strong economic component and people to people ties. Many see advantages to further enhancing cooperation on clean energy solutions and critical and emerging technologies such as quantum, artificial intelligence, and cyber security. When it comes to investment, to quote a former Australian Trade Minister, ‘Australia has no stronger or more reliable partner than the United States. Total two-way investment amounted to an impressive $1.8 trillion in 2019 — equal in scale to around 90 per cent of the value of the entire Australian share market.’21 The Australian government should look to deepen cooperation across all these areas and advance an ambitious agenda, not just in AUSMIN through the foreign and defence ministers, but also through structured bilateral dialogue on areas as diverse as trade, clean energy, climate action, science and innovation, education, and health. The Alliance should activate a wide range of 2+2 arrangements that leverage the strong strategic relationship but have relevance beyond defence and foreign policy.

Recommendation 3: Emphasise sovereignty within the Alliance

While the Australian public remain supportive of enhanced cooperation with the United States, this must be done in a way that clearly reaffirms the maintenance of Australia’s sovereignty. Sovereignty considerations have been at the forefront of questions to recent governments about the potential role of Australia in a Taiwan conflict scenario.22 They are the most frequent area of concern for Alliance sceptics and a repetitive line of attack for the small minority who oppose the Alliance.

A closer relationship with the United States will be key to helping ensure a balance of power in the Indo-Pacific as we seek to promote a strategic order that is compatible with Australia’s national interests. Doing so will drive further advances in military interoperability — even interchangeability — in the Australia-US Alliance. AUKUS, and new minilateral partnerships with the US and other countries in the region, will pose questions in terms of military access, collective posture, and capabilities. Enhanced force posture agreements with the US, which will see increased rotation of air, land, and maritime forces, will raise inevitable questions about trade-offs and sovereignty. We have already witnessed discussions about the loss of territorial control and arguments about automatic commitments to ‘hypothetical’ conflicts, including Taiwan. These debates have been characterised by claims about Australia’s supposed lack of choice.

While these are new frontiers for the Australia-US Alliance, they are challenges that have confronted other US allies around the world for decades. The key is articulating clearly that undertaking closer cooperation with the United States to advance Australia’s national interests can be achieved without diminishing sovereign decision-making. Engaging with the Australian public directly and thoughtfully on these questions will help to rationalise the logic of closer Alliance cooperation, and it will also serve to counter misinformation — some of which is targeted against Australia by hostile foreign governments — about Australia’s cooperation with its Alliance partner.

Recommendation 4: Focus on interests rather than values

Australians acknowledge that they are living in an era of rapid strategic change. Instinctively they know that the Alliance will need to change in the interests of both Australia and the United States. While values-led discussions will always gain traction with some audiences, values do not resonate on their own, including among younger Australians, as justification for doing more in the Alliance. In fact, within significant sections of the Australian population, a focus on values serves to spotlight significant differences between the two countries, especially on reproductive health care and gun laws, but also in relation to other societal issues.

While the values shared by Australia and the United States matter insofar as they are intrinsically different to the values shared by authoritarian states such as China and Russia, they are not a reason for the Alliance as such. As we move to closer security integration, Australians want changes to the Alliance articulated in terms of converging interests and the benefits to Australia and the region. At the same time, Australia and the US will bring distinctive views on their domestic and foreign policy interests — allowing space for rigorous discussion and contestation that is a necessary aspect of the Alliance. In this context, Australian governments need to ensure that national interests are foregrounded and that shared values are not the centrepiece for justifying the Alliance.

Recommendation 5: Maintain a focus on Australia’s immediate region

Australians overwhelmingly see the Alliance as a regional partnership with a Southeast Asian and Southwest Pacific focus. Our research revealed a distinct lack of interest among Australians in Alliance cooperation outside our immediate region, including the Middle East. Rightly or wrongly, Middle East operations were seen as reflective of a phase of Alliance missteps, or failures.

Many saw an opportunity for Australia to improve its international relationships by better using the Alliance in Australia’s immediate region. It was clear that the majority of participants wanted a deeper regional engagement on the part of the Australian government. They wanted Australia to not only do more in the region but also to rationalise such an approach as a core element of an independent policy that also supports and contributes to the Alliance. However, this is an area that must be navigated carefully — Australian governments must be sensitised to when it offers an advantage to lead with the Alliance in the region, and when it is best to place the Alliance in the background.

Recommendation 6: Enable deeper consultation among Australians on the Alliance

In the spirit of Peter Shergold’s observation that ‘good policy should harness the views of those likely to be impacted by the proposal,’23 the Australian government should consult regularly — and broadly — with non-expert Australians to understand wider perspectives and, where appropriate, inform approaches to managing the Alliance. Consultation, by definition, does not mean gaining approval for a proposed course of action; rather, it entails a process of meaningful discussion. Tax reform, health care, education, and other ‘domestic’ issues are portrayed as legitimate, even necessary, realms of public consultation, but defence and foreign policy are still treated as somehow off limits to non-expert consultations.

Yet, ultimately, how Australia manages the Alliance with the United States has direct implications for the security of all Australians and for national sovereignty. It is therefore highly appropriate that government institutes regular consultation forums that encompass a wide cross-section of Australians, not just elites and subject experts. Listening to what our fellow citizens have to say about the Alliance and its future will only serve to strengthen public commitment over the long term.

Appendix 1: Workshops

From February to August 2022, the project team undertook 29 face-to-face workshops with 232 individuals across every state and territory capital city with a mix of in-person and online formats. These were recruited from outreach to 548 individuals and 682 community groups and organisations.

As part of this initial outreach, the project team sent the briefing paper below. Once individuals registered to participate in a workshop and before they participated in the workshop itself, participants were sent a longer background paper prepared by the project team that further elaborated on the key themes of the briefing paper.

Appendix 2: Post-workshop survey

Following the workshops, an anonymous survey was also made available to those who were consulted. The survey elicited 150 responses. After asking to provide demographic information, the survey asked respondents to answer the following questions.

- What five words first come to mind when you think about the Australia-USA Alliance?

- In a couple of sentences, what is the Alliance for, is it important for Australia, and why?

- Briefly describe how can and should Australia leverage the Alliance to navigate the profound security challenges it confronts.

- What should future cooperation with the US look like — or not?

- How did you hear about this consultation?

Appendix 3: respondents’ demographic profile

The demographic information of the 150 survey respondents were as follows.

| Gender | Count (n) | Percentage of group |

| Male | 100 | 66.7 |

| Female | 47 | 31.3 |

| Non-binary | 1 | 0.7 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 1.3 |

| Total | 150 | 100 |

| Country of birth | Count (n) | Percentage of group |

| Australia | 98 | 65.3 |

| Other | 49 | 32.7 |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 | 2 |

| Total | 150 | 100 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | Count (n) | Percentage of group |

| Yes | 7 | 4.7 |

| No | 141 | 94 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 1.3 |

| Total | 150 | 100 |

| State/territory of residence | Count (n) | Percentage of group |

| Australian Capital Territory | 21 | 14 |

| New South Wales | 30 | 20 |

| Northern Territory | 9 | 6 |

| Queensland | 28 | 18.7 |

| South Australia | 15 | 10 |

| Tasmania | 7 | 4.7 |

| Victoria | 25 | 16.7 |

| Western Australia | 14 | 9.3 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.7 |

| Total | 150 | 100 |

| Regional status | Count (n) | Percentage of group |

| Metropolitan | 120 | 80 |

| Regional | 24 | 16 |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 | 4 |

| Total | 150 | 100 |

| Age bracket | Count (n) | Percentage of group |

| 18-29 years old | 28 | 18.7 |

| 30-39 years old | 26 | 17.3 |

| 40-49 years old | 21 | 14 |

| 50-59 years old | 24 | 16 |

| 60-69 years old | 26 | 17.3 |

| 70-79 years old | 20 | 13.3 |

| 80 years old and above | 3 | 2 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 1.3 |

| Total | 150 | 100 |

| Education level | Count (n) | Percentage of group |

| Secondary school | 11 | 7.3 |

| Diploma | 7 | 4.7 |

| Bachelor degree | 33 | 22 |

| Postgraduate degree | 97 | 64.7 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 1.3 |

| Total | 150 | 100 |

| Profession background | Count (n) | Percentage of group |

| Academic and think tanks | 46 | 30.7 |

| Manufacturing | 4 | 2.7 |

| Public service | 8 | 5.3 |

| Professional services | 31 | 20.7 |

| Students | 25 | 16.7 |

| Retired | 24 | 16 |

| Other | 9 | 6 |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 | 2 |

| Total | 150 | 100 |

Because 64.7 per cent of workshop participants completed the post-workshop survey, the survey demographics are broadly representative of the workshop participants as a whole.

Acknowledgements

As with any large-scale research endeavour, we have accumulated significant debts since this project commenced in 2021. First and foremost, we would like to thank Aliyah Ravat for providing outstanding project management support — Aliyah kept us on track, making sure that we met project milestones despite our competing schedules. Scott Blakemore’s research assistance and support throughout the project was critical to completing our program of work on time. We would also like to thank Cuong Pham who provided important data and coding analysis during the report preparation. Ryan Young from ANU’s NSC Futures Hub provided helpful input on the research design and initial test workshop in late 2021. Danielle Chubb and Ian McAllister provided the project with updated Australian Election Study data and analysis. Jill Moriarty provided graphic design support in the final stages of preparing the report. We are also grateful to Jared Mondschein, Mari Koeck and the team at USSC for their advice and support in the final stages of the report preparation.

We owe a debt of gratitude to all of those who participated in the project consultations across Australia and to the organisations and individuals who assisted us in arranging workshops — we deeply appreciate the time and insights they contributed.

Finally, we acknowledge the generous funding for this project from the Department of Defence as part of its Strategic Policy Division Grant Program (SPGP202021-0236).

The authors are responsible for all content contained in this report.