Shortages of critical medical supplies and hoarding of toilet paper, small businesses forced to close their doors, and unemployment skyrocketing. We are in a time of profound uncertainty and collectively feeling deep anxiety about our ability to meet the challenges we face.

In the midst of this, we are witnessing a highly mixed reaction from governments around the world. Some leaders seem to have lived up to the moment—issuing sober calls for calm, informing their citizens about the nature of the threat, and laying out a clear path. Others seem to be passive observers, merely reacting to unfolding events—garbled in their public statements, hesitant to take decisive actions, and unclear of what to do. And another set of leaders have performed abysmally—refusing to take responsibility, blaming others, and failing to calm an anxious public.

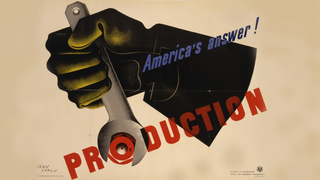

But for all the variety in national responses, one constant has been the call for a wartime footing. The French President Emmanuel Macron last week announced that “nous sommes en guerre”—we are at war. Virtually every country in the world has now issued a version of that declaration. Such calls historically have been meant to mobilize society and empower governments to do things that in ordinary times would be inconceivable. They are also meant to remind citizens that no matter how grave today’s challenges seem, there is a precedent for how democratic societies have weathered storms in the past.

Controlling the spread of the coronavirus is not the same as fighting a world war or contending with an economic depression. Nevertheless, there are lessons from America’s past that can frame how we think about this seemingly unprecedented challenge.

Controlling the spread of the coronavirus is not the same as fighting a world war or contending with an economic depression. Nevertheless, there are lessons from America’s past that can frame how we think about this seemingly unprecedented challenge. The analogy is of course imperfect. We are not facing the outbreak of foreign hostilities and our economic fundamentals are sound. But as our national conversation turns toward mobilizing the full resources of the state, our shared history can help guide what we ask of ourselves, and what we demand of our governments.

The first example comes from mid-century, when America was confronted with the Great Depression and the second World War. To spur the manufacture of necessary wartime goods, Franklin Roosevelt established the War Production Board, which was charged with converting industries from peacetime manufacturing to war production, prioritizing the distribution of materials and services, halting nonessential production, and allocating materials. American businesses rapidly converted their factories and retrained their workers to produce necessary life-saving materials. Realizing that the war had exposed dangerous shortcomings in the integrity of its supply chain, Roosevelt asked William Knudsen, an automotive executive, to oversee war production and appointed him Chairman of the Office of Production Management. Knudsen became Roosevelt’s mobilization czar, tasked with getting American business to reorganize itself for a completely new set of circumstances. “We must build them at once! You’ve got to help!” Knudsen told automotive executives. He was talking about converting automobile assembly lines to produce bombers, but today we should be talking about converting factories into production centers for ventilators, masks, PPE, and hand sanitizers. Especially as the demands of dealing with coronavirus overwhelm available supply, this is the type of effort that could serve as a reliable guide to reorienting production toward today’s needs.

Wartime efforts only rarely involved the outright government seizure of factories, but they did require carefully managing labor relations to avoid disruptions to vital industries. Roosevelt had laid the groundwork during the Great Depression by creating the National Labor Relations Board to ensure laws governing collective bargaining and unfair labor practices were enforced. During the war, this work was taken up by the National War Labor Board, which Roosevelt established to arbitrate labor-management disputes. The Board administered wage controls in industries deemed essential, prevented business from cutting salaries, and ensured there were no work stoppages that might harm the war effort. Again, this type of arrangement could not only support the production of critical supplies today, but also add some stability to the markets.

If panic buying and food hoarding continue to be a significant issue, another historical precedent could provide useful lessons.

If panic buying and food hoarding continue to be a significant issue, another historical precedent could provide useful lessons. To help regulate scarce consumer goods, prevent food shortages, and ensure that critical materials were stockpiled, the federal government introduced rationing during World War II. While Americans had been asked to voluntarily conserve their food consumption during the first World War, such voluntary efforts were deemed insufficient during World War II, when Americans undertook enormous efforts to help feed and arm war-ravaged European and Asian allies.

The government introduced a system for rationing key consumer goods, local ration boards were set up nationwide to issue ration books, and newly formed government agencies, such as the Office of Price Administration (OPA), were empowered to regulate and ration sugar, coffee, meats, and processed foods as well as tires, gasoline, and fuel oil.

Price controls were also introduced. As Roosevelt put it in his Fireside Address of April 1942, “You do not have to be a professor of mathematics or economics to see that if people with plenty of cash start bidding against each other for scarce goods, the price of those goods goes up.” He called on Congress to undertake an economic program that would include wage stabilization, rent and price controls, and comprehensive rationing that ensured “an equality of sacrifice” across the country. At its peak, nearly 90 percent of food prices and nearly 80 percent of rental housing stocks were frozen. Moreover, when it detected a critical shortage, the OPA was authorized to subsidize production of certain commodities.

Another key lesson can be found in the communication strategy of President Roosevelt. Roosevelt was a masterful communicator and ensured that the public was kept up to date on the war’s progress, informed of setbacks, and readied for the enormity of the sacrifices and efforts to come. He initiated weekly radio addresses, known as fireside chats, at the beginning of his presidency in 1933 and used them throughout the war to reassure an agitated public, combat disinformation campaigns, and explain government policies.

Roosevelt also used his public speeches to reinforce the global nature of the challenge Americans were facing, consistently making the case that only globally-coordinated solutions could defeat threats that crossed borders. “Let no one imagine that America will escape, that America may expect mercy, this Western Hemisphere will not be attacked and that it will continue tranquilly and peacefully,” he warned in October 1937. In words that are too close for comfort today, Roosevelt referred to conflict in Asia and Europe as an “epidemic of physical disease,” which necessitated concentrated and coordinated international efforts to “quarantine . . . the patients in order to protect the health of the community against the spread of the disease.”

Finally, the historical experience of wartime measures offers the point that existential threats often necessitate extraordinary political coalitions. Nowhere is this more true than for democratic governments, where political division is hardwired into the system. The smooth functioning of a government moving to enact sweeping new policies requires legitimacy if it is to succeed. In parliamentary systems, a national unity government was often formed to bring the political opposition into the governing coalition. This is harder to accomplish in a presidential system, but by no means impossible. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln intentionally formed his cabinet to include various wings of the Republican Party and invited non-secessionist Democrats into the cabinet. This was the impetus behind the creation of his famed “team of rivals”. That, and deft politics, is also the reason Franklin Roosevelt appointed two prominent Republicans, Frank Knox and Henry Stimpson, to run the Navy and War Departments. Roosevelt declared that these appointments were intended to inspire “national solidarity in a time of world crisis and on behalf of national defense.”

But for all of the lessons which can be drawn from the effective use of wartime footing in our recent history, the most important difference today is that the crisis is simultaneously both a pandemic and an impending threat to the global economy.

But for all of the lessons which can be drawn from the effective use of wartime footing in our recent history, the most important difference today is that the crisis is simultaneously both a pandemic and an impending threat to the global economy. Moreover, many of the actions undertaken to put the United States on a war footing in the 1940s were natural outgrowths of Franklin Roosevelt’s decade-long attempt to equip the federal government with new capabilities and grant it the necessary authorities to overcome the Great Depression. The creation of new agencies and organizations was second nature to that generation, as was a willingness to experiment boldly, persistently, and swiftly on what might provide immediate relief for millions of affected Americans. Those habits have long since been forgotten.

But as the severity and duration of the coronavirus pandemic deepens, we will all be called on to mobilize our societies. Drawing from past lessons, this will include determining whether—and how—to manufacture more life-saving equipment, ration goods, control prices, and navigate likely labor shortages and disruptions as workers fall ill. And Franklin Roosevelt’s political efforts point to one useful model for keeping the public up to date on wartime efforts, informing them of setbacks, combatting domestic and foreign disinformation campaigns, urging them to coordinate global actions, and readying them for the enormity of the sacrifices and efforts to come.

In this regard, it might not have been Franklin but Eleanor Roosevelt who provided the most enduring wisdom. “We do not have to become heroes overnight,” she once wrote. “Just a step at a time, meeting each thing that comes up, seeing it is not as dreadful as it appears, discovering that we have the strength to stare it down.”