In January 2026, the second Donald Trump administration released its National Defense Strategy, a month after the release of its 2025 National Security Strategy. Though it breaks with the blueprints of the first Trump administration (2017-2020) and the Joe Biden administration (2021-2024) in notable ways, the 2026 document also exhibits considerable — if more subtle — continuity in other areas. This explainer looks back on the 2018 and 2022 NDS to contextualise this most recent document, before unpacking what the 2026 strategy says about the administration’s global defence priorities, its approach to China, and its expectations of alliances and partnerships.

What is the National Defense Strategy?

Every four years, the US Office of the Secretary of Defense is required by law to issue a new National Defense Strategy (NDS). A derivative of the incumbent administration’s National Security Strategy (NSS) published by the White House, the NDS explains how the Pentagon will contribute to fulfilling the President’s national security objectives. As mandated by Congress, the NDS articulates the priorities and objectives of the Department of Defense (DoD) and assesses the state of US force posture, situating this within the Pentagon’s assessment of the global strategic environment. The NDS serves multiple purposes — it provides broad strategic guidance to defence and military officials, outlines the DoD’s approach to US alliances and partnerships, and serves as a key reference point for subsequent resourcing requests to the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and Congress. There are usually two versions of this document: a public-facing summary document that captures the key contours of the strategy, and a more detailed classified version that informs Department and Congressional action on resourcing and execution.

What did Trump’s first NDS say?

Interpreting the second Trump administration’s NDS requires looking at its first. The 2018 NDS marked a departure from previous strategy documents in its characterisation of the global security environment and the US force planning construct required to address it. For the first time since the end of the Cold War, this document argued that “inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism,” was now the Pentagon’s primary occupation. Chinese and Russian economic and military modernisation and their shared intention “to shape a world consistent with their authoritarian model” posed the greatest threat to US national security interests around the world. These challenges were compounded by a weakening of the rules-based international order, and a relative decline in US military power to the extent that it no longer enjoyed “uncontested or dominant superiority in every operating domain.”

While the underlying concept of ‘Great Power Competition’ drew criticism for its lack of operational clarity and its conflation of the threats posed by China and Russia, the 2018 NDS was broadly well received for its sober assessment of major changes in the global strategic environment and, by extension, the equally significant changes required to US alliance management and force structure to meet those challenges.

This assessment informed a major reappraisal of US force structure and global posture priorities. As explained by Elbridge Colby, the principal author of both Trump administration’s strategies and Deputy Assistant Secretary for Defense Strategy and Force Development in 2018, reorienting the Pentagon for great power competition would require “a fundamental shift” in Pentagon planning and investment priorities, including deprioritising persistent but lower-level threats from non-state actors (terrorist groups and insurgencies) and ‘rogue’ regimes like Iran and North Korea, and assuming that the United States would be capable of sustaining war with only a single major power (i.e. China or Russia) in one theatre at a time. To meet these challenges, the NDS posited allies and partners as the United States’ “durable, asymmetric… advantage,” though it also called for efforts to empower these countries to contribute to collective security and to better manage their own interests through arms sales, technology transfer and information-sharing. While the underlying concept of ‘Great Power Competition’ drew criticism for its lack of operational clarity and its conflation of the threats posed by China and Russia, the 2018 NDS was broadly well received for its sober assessment of major changes in the global strategic environment and, by extension, the equally significant changes required to US alliance management and force structure to meet those challenges.

Did Biden’s 2022 NDS change course?

Despite the political transition in the White House, the 2022 NDS explicitly continued with the direction of the 2018 NDS in its adoption of great power competition as its chief organising principle. However, it further narrowed the Pentagon’s threat prioritisation, identifying China as the United States’ “most consequential strategic competitor” and the Indo-Pacific as the DoD’s “priority theater.” This distinction between the long-term “pacing challenge” of Beijing and the “acute threat” of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, which had delayed the publication of both the 2022 NSS and NDS by several months, marked a shift from the 2018 NDS, which seemingly equated both powers. The Pentagon reflected this prioritisation by pursuing a smaller force structure focused on deterring great power competitors and reducing forward deployments to secondary theatres, pledging to ensure that small-scale crises would not undermine “high-end warfighting readiness.”

This distinction between the long-term “pacing challenge” of Beijing and the “acute threat” of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, which had delayed the publication of both the 2022 NSS and NDS by several months, marked a shift from the 2018 NDS, which seemingly equated both powers.

At the same time, the Biden administration’s NDS also broadened the DoD’s threat aperture beyond military threats alone. Alongside second-tier threats from North Korea, Iran and violent non-state actors, the 2022 NDS also listed climate change, global pandemics and technological diffusion as among a host of multi-domain, interconnected global threats that would threaten US security over the coming “decisive decade.” It proposed to address these challenges through an ‘Integrated Deterrence’ framework, “weaving together all instruments of national power” and situating the Pentagon as part of an interagency approach to deterring the United States’ adversaries and meeting its national security objectives. Though this concept was criticised by some experts as vague and ill-suited for a defence planning construct, alliances and partnerships were nevertheless considered the “center of gravity” for this strategy — indeed, the strategy was reportedly drafted in consultation with many of these countries. As in 2018, the 2022 document emphasised alliance modernisation over burden-sharing, pledging deeper cooperation with allies on warfighting concepts, military technologies and intelligence sharing, with the objective of creating a “latticework” security architecture of mutually reinforcing regional and global partnerships.

So how does the 2026 NDS depart from those trends?

The 2026 NDS actively seeks to distinguish itself from the “grandiose strategies of the past post-Cold War administrations,” including Trump’s 2018 NDS. Absent is any mention of ideological or strategic competition between great powers or the prevalence of interrelated global threats. These are replaced by an emphasis on economic interests, homeland security and immigration, and geographical rather than global challenges. The document denounces the “cloud-castle abstraction” of the international rules-based order as actively detrimental to US interests, generally treats alliances and partnerships as burdens to be shifted rather than as inherent advantages, and declares an end to US interventionism abroad despite early operations against Cuba, Iran and Venezuela. The 2026 NDS also takes unusually strong cues from the 2025 National Security Strategy, reflecting the degree to which the White House dominates the interagency foreign policy process — President Trump is mentioned 47 times in 2026, compared to 0 times in 2018. Strangely, it often offers far less insight into the Pentagon’s implementation plans for its own strategy than the NSS does, particularly with respect to the Indo-Pacific.

What’s with the focus on the Western Hemisphere? Is the Indo-Pacific still a priority?

As with every previous US defence strategy, the first priority of the 2026 NDS is the defence of the homeland, including through missile defence, nuclear modernisation, cyber defences and countering violent extremist threats. However, this document adopts an expanded concept of the homeland that is inclusive of the entire ‘Western Hemisphere’, a region stretching from the Arctic to Argentina. To deliver the “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine,” the NDS says that the Pentagon will simultaneously protect the homeland and “restore American military dominance in the Western Hemisphere” through prioritising border security missions, counter-narcotics operations, securing key land and sea lanes, and denying non-Hemispheric competitors access to key commercial assets or strategic positions across the region. In that respect, the NDS is as descriptive as it is proscriptive, coming in the context of a prolonged strike campaign against alleged “narco-terrorist” vessels; an extensive build-up of US combat forces in the Caribbean (including reassignments from the Indo-Pacific); the ousting of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro; and contentious diplomacy over Greenland and the Panama Canal.

What this means for the Indo-Pacific is unclear. On the one hand, the document frames the Indo-Pacific and the Western Hemisphere as equal priorities when justifying posture reductions in Europe, and casts preeminence at home as a precondition for projecting military force across the globe from the continental United States, including into Asia. Yet the administration’s NSS also warns of a “readjustment of our global military presence” that favours addressing hemispheric threats over other theatres, suggesting a clearer hierarchy of priorities. This marks a shift from the DoD’s March 2025 Interim National Defense Strategic Guidance, which reportedly linked “defending the U.S. homeland” in the traditional sense with the “sole pacing scenario” of preventing Chinese military action against Taiwan. Several experts have noted that the Pentagon’s objectives of achieving denial in the Indo-Pacific, dominance in the Western Hemisphere and sustainment of a US-based global strike force each necessitate very different force structures that come with their own posture and budgetary trade-offs. Ultimately, the NDS fails to answer the question of how these concurrent force structure goals will be achieved.

How does the NDS characterise China?

The 2026 NDS differs markedly from its predecessors in its characterisation of the US-China relationship, not so much in terms of whether China matters as to why it matters. The language of a global multi-domain “strategic competition” is replaced by a greater emphasis on preserving US economic interests in Asia and on providing the “undergirding strength” for the President’s diplomatic engagement with Beijing to that end, ahead of an expected summit with Xi Jinping in April 2026. It endeavours to reassure Beijing that the Administration does not seek regime change nor to dominate or humiliate China, but rather a balance of power “on terms favourable to Americans but that China can also accept and live under.” To that end, it says the United States will pursue “strategic stability” through expanded dialogue with the People’s Liberation Army focused on “deconfliction and de-escalation.” The document also seems to hint that the Trump administration sees a “legitimate” role for China in a changing regional order, though it provides little detail on what that should look like. Regardless, these framing changes have led former senior Asia officials to worry that the Trump administration may be softening its China policy settings across a range of indicators in pursuit of limited economic gains.

The NDS endeavours to reassure Beijing that the Administration does not seek regime change nor to dominate or humiliate China, but rather a balance of power “on terms favourable to Americans but that China can also accept and live under.”

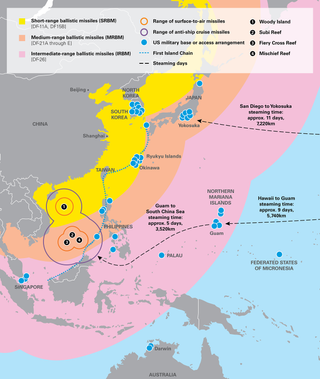

The 2026 NDS similarly assesses the Chinese military threat and required response through an economic lens, yet also exhibits a high degree of continuity with its predecessors when it comes to implementation. It warns that Chinese regional military pre-eminence would allow it to “effectively veto Americans’ access to the world’s economic center of gravity” and diminish Washington’s “ability to trade and engage from a position of strength.” It proposes to prevent that through a “strategy of denial” along the First Island Chain (FIC), a model long-championed by now-Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Elbridge Colby. This approach is consistent with prevailing US regional military strategy across successive NDS documents, further evidenced in the broad continuity between Biden and Trump on alliance modernisation and military posture across the region. However, the document is notably short on the particulars of that strategy, including absent details on the force structure changes required to implement a denial strategy in Asia while simultaneously executing Western Hemispheric dominance; the role of allies beyond hosting US forces and spending more on defence; and the lack of explicit mentions of Taiwan.

Figure 1. China’s growing missile threat to US bases and regional access locations

What does the document say about the United States’ alliances?

The United States’ alliances occupy a central place in the 2026 NDS, though they are cast primarily in terms of obligations more so than their enduring benefits for US strategy. Indeed, while alliances are one of the document’s four key lines of effort, they are addressed almost exclusively through the lens of ‘burden-sharing’, with a focus on compelling allies “to assume primary responsibility for their regions” and to “shoulder their fair share of the burden of our collective defense.” By more equitably distributing security burdens, the document says that allies and partners should help to maintain “favorable balances of power in each of the world’s key regions.” A primary indicator for whether or not allies are meeting these requirements is a “new global standard of allied defense spending” of 3.5% of GDP, one which now applies as much to Asia as it does to Europe. Yet the Administration’s expectations of allies in different regions appear to vary. For instance, requirements in Europe and the Middle East are couched in terms of “burden-shifting” with allies assuming greater leadership on conventional defence matters as Washington scales down its own commitments. By comparison, requests of allies in the Indo-Pacific are framed in terms of maximising their contributions to “collective” defence objectives, suggesting an enduring US military presence along the frontlines of regional hotspots, with the glaring exception of the Korean Peninsula.

In fact, strip away the America First window dressing, and it is clear that Washington continues to see alliances as essential to the United States’ position in Asia as they ever have. Specifically, strong alliances and more capable allies figure as essential to achieving the “favorable balance of military power” required to prevent Chinese military action across the FIC. The NDS also echoes calls made in the NSS for all of the United States’ regional defence relationships — not just its treaty alliances — to be more squarely oriented towards those requirements. Though the NDS has little to say about this beyond burden-sharing and arms sales, it also says that incentivising allied contributions will require efforts to “empower” those countries to do so. It’s unsurprising then that the Trump administration has persisted with long-standing US alliance modernisation agendas in Asia intended to do just that, including expanding operational and industrial cooperation with priority partners across the region, such as through AUKUS. This resonates with Canberra’s goal of “maintaining a favourable regional strategic balance” through strengthening sovereign capabilities and increasing effective defence partnerships, as stated in Australia’s own 2024 National Defence Strategy. In that sense, allied self-strengthening measures shouldn’t be read as mere responses to the Trump administration’s exhortations to increase defence spending, even though these demands are undoubtedly influencing fiscal timetables in allied capitals.