China’s September 3 military parade commemorating the 80th anniversary of the defeat of Japan was meant to intimidate the world with a dazzling display of modern firepower, including ballistic missiles, drones, air defence lasers, and even robot dogs.

The message was about the future – China is “unstoppable”, the West is declining, and resistance is futile.

But the commemoration also featured the weaponisation of something just as important to Xi Jinping and the Chinese leadership as military hardware – narratives about the past.

His language is replete with references to the inevitability of the future based on the forces of the past.

Xi is a Marxist, not so much in his enthusiasm for world revolution but rather in his embrace of the logic of dialectical materialism. His language is replete with references to the inevitability of the future based on the forces of the past. Thus, China will always stand on “the right side of history” and unification with Taiwan is an “irresistible trend and a righteous cause”.

In part, this is messianic absolutism. Dialectical logic was the root not only of Marxism but also of Kant, the enlightenment, and liberalism. But in its origins the linear thinking about history was rooted in St Augustine and the certainty of the eschaton and thus the moral logic of jus ad bellum – the concept that the inevitability of history is itself moral justification for brutally sweeping away all those who resist.

With the enlightenment that moral frame was challenged and the concept of jus in bello – the justness of conduct of war – rose as a counterbalance to the idea that divine ends justify all means.

This enlightenment turn largely informs Western democratic approaches to international security today. However, Marx and Lenin never accepted that premise, and implicit in Xi’s dialectical determinism is a chilling emergence of jus ad bellum with Chinese characteristics.

Asserting the inevitability of world events based on the forces of history also requires dominating the interpretation of those forces. All nation states engage in that game to some extent, of course. Canadian and American high school textbooks have very different narratives about the American Revolution and the war of 1812, for example, since those conflicts were so foundational to both countries’ national mythologies.

Even Australians and Kiwis cannot agree on the origins of pavlova. But historians across those borders can agree on the basic facts even if they emphasise different dimensions.

For the Chinese Communist Party, the presentation of history is of such existential importance that facts are wielded as weapons without historical review or internal contestation – not only to reinforce the CCP’s mandate but to delegitimise external rivals.

This weapon was on full display with the 80th anniversary celebrations in Beijing.

The CCP, we were told, defeated Japanese imperialism almost single-handedly. In fact, as contemporary historians like Rana Mitter have chronicled and Mao Zedong acknowledged to a visiting Japanese prime minister in the 1970s, it was Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Kuomintang that bore the overwhelming brunt of the fighting – armed largely by American lend lease while American, Australia, Indian and other troops put Japan on the defensive from Burma to the Pacific. And, of course, it was the Soviets who delivered the coup de main in August 1945 by invading North China through Manchuria, which then provided a sanctuary for the CCP to take on the exhausted KMT.

Chinese ambassadors in Canberra regularly remind their Australian counterparts that Australia and the CCP were on the same side during the war and that Japan was and should remain the threatening out-nation – ignoring polls that show Australians trust Japan more than any other country in the world.

The CCP also uniquely sources its contemporary territorial claims and international standing to the summits at Cairo, Yalta and Potsdam during World War II. According to Beijing’s interpretation, these summits established China’s claims to Taiwan in the East China Sea and permanently placed China on the “right side of history” and Japan as the enduring threat to peace. Chinese ambassadors in Canberra regularly remind their Australian counterparts that Australia and the CCP were on the same side during the war and that Japan was and should remain the threatening out-nation – ignoring polls that show Australians trust Japan more than any other country in the world.

When I was the senior official in the White House responsible for Asia policy, I found myself constantly countering Beijing’s cherrypicking and reinterpretation of history – and that pattern has only intensified under Xi. Chinese scholars regularly produce obscure texts that allegedly prove China’s ancient claims over the entirety of the South China Sea; that the communiques Chinese leaders issued with presidents Nixon, Carter and Reagan somehow contain an unconditional US commitment to cease selling arms to Taiwan; that agreements recognising Beijing diplomatically also establish the PRC’s control over Taiwan; or that once independent kingdoms in Koguryo (North Korea), Manchuria, Tibet, Xinjiang, and Taiwan were always immutable parts of Chinese civilisation.

Historians outside of China agree with almost none of these interpretations but within China’s academy and think tank world, these mythologies are developed without peer review and then deployed in celebrations like the 80th anniversary where scores of historically illiterate or disinterested leaders sit obediently as VIPs – or, like Putin, find the narratives strategically useful.

This manipulation of history is as old as the CCP itself but has expanded with Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions. The myth that the party defeated Japan was foundational and is redeployed whenever there are internal challenges to CCP legitimacy like the Tiananmen Incident.

The assertion that Cairo, Yalta and Potsdam provide the definitive framework for post-war order dates to the PRC’s establishment of relations with the West and remains a regular staple of exhortations to friends in Australia, Europe or America to remember the common cause against Japan and to remain on the “right side of history”.

The newest twist under Xi is the use of history to delegitimise the US and the “West”.

Previous leaders such as Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao largely avoided that confrontational approach (I was in their summits with president George W. Bush and witnessed how careful they were to avoid spurring US countermoves).

But Xi has taken a page from Japan’s Greater East Asian Co-prosperity Sphere when militarists in Tokyo claimed that Imperial Japan alone could stand-up for downtrodden Asians against Western imperialism.

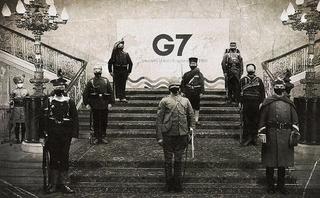

Xi began using the “Asia for Asians” mantra in a speech in Shanghai in 2014 and has turbocharged the narrative since. When G7 foreign ministers met in 2021 and criticised China’s foreign policies, Chinese state-owned media disseminated computer-generated photos that depicted the seven foreign ministers in the uniforms of their countries during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 (the US secretary of state dressed as a US Marine, the Japanese foreign minister in an Imperial Japanese army uniform, the British foreign secretary in khaki and pith helmet, and so on).

It was a clever propaganda play since all seven countries did have troops fighting the Boxers – though the idea that the Boxers were standing up for Asia against Western imperialism is a stretch. More broadly, China’s “Global Civilisation Initiative” is predicated on the idea that before the West, the cultures of Asia, Africa and the Middle East enjoyed a harmonious existence that must now be tapped to resist culturally inappropriate universal values such as democracy or human rights. Putin’s Russia – one of the most rapacious imperial powers of all – finds this narrative particularly useful and works with China to propagate it across South and Southeast Asia.

This larger anti-Western civilisational discourse is so full of holes that it should be easy for democratic governments and international scholars to discredit. In multiple opinion surveys taken in Asia, for example, democratic values consistently top the list of norms that citizens want – not a return to traditional pre-Western political values (though pride in one’s own culture is, of course, high). The notion that somehow the Central Kingdom served as a buttress against the West on behalf of barbarians elsewhere in the region is risible, as is the assertion that China’s tributary system was a source of harmony and tranquillity as Chinese scholars and propaganda claim (the Korean peninsula alone was attacked hundreds of times by various Chinese dynasties).

While some countries in Southeast Asia are more susceptible to these narratives because of their own colonial experience, that would not be true of Japan, The Philippines, Korea or other states on the receiving end of Beijing’s hegemonic ambitions. Yet the democracies are dreadful at finding a counter-narrative. One problem is that the academy is also full of anti-Western postmodernists who are sympathetic with the larger Chinese argument, if not the flimsy methodologies.

Another problem is how few democratic leaders understand history themselves. There are no Churchills or JFKs or Abe Shinzos on the scene who understand the role of the past in the geopolitics of the present.

Another problem is how few democratic leaders understand history themselves. There are no Churchills or JFKs or Abe Shinzos on the scene who understand the role of the past in the geopolitics of the present. Certainly not US President Donald Trump, who is happy to throw away three decades of US-India strategic alignment with tariffs that only drive Modi closer to Beijing.

Finally, democracies are just plain bad at these narrative games. The US government cannot even agree on what the challenge is, with the State Department calling for public diplomacy and the Pentagon preparing for “cognitive warfare”.

If the US government cannot agree among itself on what to do, how could allies co-ordinate with each other?

Perhaps that is a reminder that the greatest weakness in Beijing’s manipulation of history is that it does look like propaganda.

The inability of democratic governments to produce similar results may be a blessing in disguise. Time will tell. For now, however, history is a battlefield where Beijing is on the offensive – and the narrative weapons on display this past week should not be ignored.