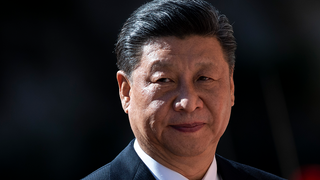

Chinese President Xi Jinping is conducting a war on three fronts: to control and eventually reduce the spread of COVID-19 within China, shut down discussion about the failings of the one-party state and its authoritarian institutions, and salvage his personal standing and reputation.

Although China is not out of the woods, the good news is that new cases of infections are slowing. With respect to the second and third fronts, Beijing has shifted from defence to offence in boasting to the world about its decisive and extreme response.

Galling as it is that Beijing refuses to admit any fault, global co-operation to contain the virus and find a vaccine — including with China — is essential. But the Chinese Communist Party is also promoting itself as a model to much of the developing world. Putative leaders who cannot acknowledge errors cannot exercise effective leadership.

Chinese state media has run prominent articles praising Xi as having a “pure heart like a newborn’s that always puts the people as his number one priority”. The same outlets are extolling Xi as a determined leader who led a “people’s war” against COVID-19 and saved his country from disaster.

From a political perspective, COVID-19 is deeply troubling for the party because it changed the conversation from how quickly China can construct a 1000-bed hospital, build a dam, or commercialise self-driving cars to how the country is ruled and governed.

Innumerable posts by internet citizens mocking such official messages had to be suppressed by government censors, indicating Chinese citizens are not so easily fooled. Li Wenliang, the doctor who treated patients on the frontline and was detained for spreading “false rumours” when he alerted colleagues to the seriousness of the virus in December, has become a national hero since his death. While it was local officials who detained Li, the ever more centralised control of public messaging has occurred under Xi’s rule. No army of censors will win Xi this personal public relations battle, even if his hold on power is probably safe.

Of more importance to the Communist Party and the rest of the world are the attempts by Beijing to control and strongarm governments about how to talk about COVID-19.

From a political perspective, COVID-19 is deeply troubling for the party because it changed the conversation from how quickly China can construct a 1000-bed hospital, build a dam, or commercialise self-driving cars to how the country is ruled and governed. Initial attempts to control information and suppress dissent rather than prevent a health crisis posed awkward questions about the strength and resilience of Chinese society under authoritarian institutions.

As Li said in an interview shortly before his death: “I think a healthy society should not only have one kind of voice.”

With the economic disruptions, it is clear this is not just a matter of interest for social scientists and political philosophers. For many businesses, China remains an attractive place to base manufacturing operations or to make some money in the short term. But perceptions of the resilience, reliability and trustworthiness of its political economy will influence whether global institutional investors and superannuation funds will park their capital in the country, if multinationals will continue to invest tens of billions in China as a long-term bet, and whether the renminbi can become a genuine store of value.

Despite propaganda about self-sufficiency, China needs the world and advanced markets most of all. All these factors will determine whether Xi’s grand economic plans, such as the Belt and Road Initiative and Made in China 2025, can succeed.

This is one reason why politics and strategic messaging was first and foremost on Xi’s mind and remains that way. Beijing achieved a major public relations coup when the World Health Organisation turned a blind eye to the party’s governance deficits, which helped the virus to spread, and dutifully applauded the country’s “extraordinary efforts” to combat that spread once the horse had bolted.

Despite propaganda about self-sufficiency, China needs the world and advanced markets most of all.

At a time when an obvious health crisis was brewing, Beijing bothered to revoke the press credentials of three Wall Street Journal reporters after the paper published an opinion piece by celebrated American political scientists Walter Russell Mead entitled The Real Sick Man of Asia.

China reportedly turned down three offers of US assistance to send health experts into Wuhan in January to better understand the virus. It only allowed in American help as part of a WHO mission early last month. This occurred while Chinese diplomatic missions around the world castigated governments, including Australia’s, for erecting travel bans when they were simply taking prudent steps to protect their citizens.

The same obstinate mindset is now apparent in Beijing referring to using terms such as “China virus” or “Wuhan coronavirus” — as Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo have done — as despicable, xenophobic and racist. It is no such thing.

It is not unusual to refer to a virus according to its origins such as the 1918 Spanish flu or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, or MERS. Of more pertinence is that recognising the origins of the virus leads to a necessary debate about China’s institutions and the adaptability of those for sustained growth and global leadership, just as we openly engage in debates about the strengths and weaknesses of the US political-economic system.

No one pretends that the 2008-09 global financial crisis did not originate in the US.

The very fact that COVID-19 originated in China — the world’s second-largest economy — and then spread in the way it has makes that discussion more, rather than less, important.