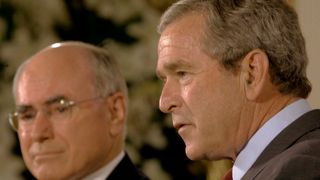

The Australia–United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA) turns 20 this year. When it came into force in 2005, the world was in the midst of a quite different era of trade policy. The United States was Australia’s third-largest trading partner, globalisation was in its heyday and the appetite for free trade agreements (FTAs) was high. Both the US President at the time, George W. Bush, and Australia’s Prime Minister, John Howard, were staunch advocates for trade liberalisation.

Today, the world’s two largest economies, the United States and China, have turned away from trade liberalisation. Trade policy has shifted from reducing trade barriers and increasing consumer choice and capital flows to more protectionist policies that preference domestic workers and industry in the name of national security. Under President Donald Trump, the United States is increasingly viewing trade as a zero-sum game of winners and losers, seen primarily through the lens of trade balances, while policy and regulation of trade offer a suite of negotiating tactics.

This explainer explores the Australia–US trade and investment relationship’s evolution across the past 20 years — from AUSFTA’s initial negotiations in 2003 to the state of trade in 2025 and its future in a world increasingly shaped by competition over technology, national security and economic strength.

What is AUSFTA?

Bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) give countries the opportunity to negotiate changes to one another’s regulations and policies. Traditionally, FTAs have focused on reducing tariff rates for different goods and sectors, allowing exporters to access and be more competitive in overseas markets, while also addressing regulation regarding investment, intellectual property and state subsidies.

Negotiations for an Australia–US free trade agreement began in 2003. After six rounds of negotiations that concluded in May 2004, AUSFTA came into force on 1 January 2005. AUSFTA contained agreements on:

- Tariff reduction: AUSFTA eliminated most tariffs on goods traded between the two countries. Average tariffs on Australia exports into the United States fell from 3.8% in 2002 to 1% by 2008, while average tariffs on Australian imports from the United States fell from 4.6% in 2002 to 1.2% in 2008. There were notable exemptions to tariff reductions, with the United States refusing to reduce its protections for its sugar and dairy industries.

- Services trade: The agreement contained commitments that both countries would treat service providers from the other country equally to their domestic providers. This included working on domestic barriers like mutual recognition agreements for professionals and following merit-based criteria for procurement.

- Pharmaceuticals: One of the most controversial chapters of the agreement in Australia, AUSFTA changed Australia’s Pharmaceuticals Benefits Scheme, which sets prices for medicines, to incorporate the value of R&D and ‘innovative’ medicines into its calculations.

- Agriculture: Often a divisive issue in free trade negotiations, the United States secured protectionist export quotas on Australian beef, dairy and horticulture products — allowing it to limit Australian imports into the United States. Australia’s strict biosecurity regulations, which can act as non-tariff trade barriers, also came under scrutiny, with AUSFTA establishing channels to negotiate biosecurity standards between the two countries (the 2003 ban on Australian imports of US beef was repealed in 2019 and is currently under review in the context of US tariff negotiations).

- Investment: Australia’s threshold for triggering investment screening from the United States was raised from A$50 million to A$800 million, enabling US investors to more easily make investments in Australia. AUSFTA also drove broader amendments to Australia’s rules around foreign investment from all destinations.

- Intellectual property: Australia extended its copyright protection from 50 to 70 years, to align with those of the United States.

Examining impact: Assessments of AUSFTA

Untangling the impact of an FTA from broader macroeconomic trends is complicated. Data from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade indicates that in 2018, the utilisation rate of AUSFTA (i.e., the proportion of trade that enters under FTA preference) in Australia was 88% for exporters and 78% for importers. Utilisation rates tend to be higher for agricultural and metal products and lower for manufactured goods.

Studies completed both in advance of and since its implementation have been inconclusive regarding AUSFTA’s overall impact — suggesting it has aided certain parts of the relationship (e.g. investment flows), while having middling impacts on goods and services trades, with strong variance between sectors.

Studies have been inconclusive regarding AUSFTA’s overall impact — suggesting it has aided certain parts of the relationship (e.g. investment flows), while having middling impacts on goods and services trades, with strong variance between sectors.

A 2001 Centre for International Economics report, commissioned by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which pre-dated actual negotiations and so modelled the vague contours of AUSFTA, concluded the agreement would produce improvements for both the United States and Australia in both welfare (real household consumption) and production (GDP) terms. The modelling estimated that across 20 years (from 2000 to 2020), at net present value, the benefits for Australia would total US$9.9 billion in real household consumption and US$15.5 billion in GDP, while for the United States they would total US$10.3 billion and US$16.9 billion respectively.

A subsequent 2004 report, also by the Centre for International Economics, included updated modelling to reflect the contents of AUSFTA. The revised analysis estimated the 20-year benefit of AUSFTA to Australian GDP at US$55.2 billion and suggested that by 2010 the yearly boost to real GDP would have reached A$6.1 billion (largely due to tweaks in investment regulations). However, a counter-analysis in a 2004 paper by Dr. Philippa Dee from the Australian National University contended that the benefit to Australia would be far lower — closer to A$53 million per year, with similar figures suggested by other studies. An Australian Senate Select Committee’s 2004 inquiry into AUSFTA, which summarised the above studies alongside other AUSFTA assessments at the time, concluded that, while some “results indicated substantial gains for Australia, others found the gains to be minimal.”

A 2010 Australian Productivity Commission report argued that bilateral FTAs have limited benefits, with the main one being favourable treatment of your country’s goods over countries without an FTA. The report found anecdotal survey evidence that AUSFTA’s tariff reductions and procurement reforms had increased opportunities for Australian manufacturing and agricultural exporters but offered fewer benefits to services.

Other, more recent research suggests the FTA had mixed effects on Australia’s economy. A 2015 study by Shiro Armstrong of the Australian National University found that AUSFTA led to trade diversion — where countries preference less-efficient suppliers from their FTA counterpart that face lower tariffs, instead of the absolute lowest-cost supplier available. Another 2012 study by the University of Technology Sydney’s Stephen Kirchner concludes that reforms to Australia’s foreign investment screening mechanisms as part of AUSFTA had positive impacts. This includes on overall — not just US — FDI flows into Australia and total FDI stock (to the tune of A$74.7 billion by June 2011), albeit also generating a tariff-jumping effect — where foreign firms locate directly in the destination country to ‘jump’ over the tariff wall.

In marking the fifteenth anniversary of AUSFTA, USSC produced a report that examined the agreement’s effects, particularly on investment between the countries — pointing to its impacts on bilateral investments and the role of cultural factors in enabling greater trade and investment, with a common language, shared history and institutional similarities all important. Further, in this piece, Stephen Kirchner, in re-running the model from his 2012 study concludes that by March 2020, FDI was A$92.3 billion higher than would have been expected. In an accompanying USSC event, Bob Zoellick, lead US negotiator for AUSFTA, noted that the fundamental basis for the agreement was “to deepen and extend the network of economic ties and, of course, that begins with the trade barriers, but we really saw it as something much more, we saw it as trying to encourage the two-way investment and business links...to connect Australia to US innovation...[and] more of those people-to-people ties.”

How has Australia–US trade changed?

The overall trade relationship between Australia and the United States has stayed relatively steady over the past 20 years. The value of trade has increased since 2005, rising from A$45 billion in FY2005/06 to A$126 billion in FY2023/24 but US share of total Australian trade has remained stable, hovering around 10% (see Figure 1). There has been a slight fall in the United States’ relative importance as a goods trading partner as Australia traded more with booming Asian economies. Yet, this was offset by increases in the share of services trade as technology has enabled better access to US digital services like software and media. The story is similar when looking at total US trade — reasonably consistent shares of goods and services trade across the last 20 years, with the greatest variation in Australia’s imports of US services.

Goods trade

In FY2023/24, the United States accounted for four per cent of Australia’s goods exports and 12% of goods imports.

Australia’s largest export industry to the United States is agriculture, in particular beef and lamb. Across the past two decades, two-way trade in biotechnology has seen the largest increase, as Australia’s own biotechnology industry has grown. Most US exports to Australia are machinery — including cars, trucks, tractors, aircraft, and engineering equipment — which are crucial inputs into major Australian industries like agriculture, construction and mining.

Services trade

An important aspect of the Australia–US economic relationship, services trade includes tourism and travel, attending university overseas, licensing a film made overseas, and engaging an overseas firm to provide engineering, consulting, or accounting services. Australia’s services exports to the United States have tripled since FY2004/05, reaching A$16 billion in FY2023/24 (see Figure 5). The United States is Australia’s second-largest services export destination, with financial services and the use of each other’s intellectual property seeing particularly notable increases.

The United States has consistently been Australia’s largest source of services imports. Australia’s imports of services from the United States have risen significantly since FY2004/05, totalling A$39 billion in FY2023/24, driven by increases in intellectual property, culture and recreation, and other business services (a broad category which includes management consulting, engineering and accounting services).

Investment

Investment is a key part of the US–Australian economic relationship. Investment can broadly take the form of either foreign direct investment (FDI — where a foreign investor has significant control over its investment, such as a US firm acquiring a stake in an Australian company or investing earnings to expand its Australian business); or portfolio investment (such as investing in bonds or buying smaller amounts of stocks).

Since 1998, the United States has been the largest source of foreign investment into Australia and is also the largest destination of investment from Australia. In the last two years, for the first time, Australia had more invested in the United States than vice-versa — sitting at A$1.55 trillion versus A$1.35 trillion in 2024 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Stock of two-way Australian and US investment (2001–2024)

The future of the US–Australia trade and investment relationship

The world has changed since 2005. Between 2000 and 2012, the United States signed FTAs with 17 countries. But since the election of President Trump in 2016 and the subsequent US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, US leaders on both sides of the aisle have altered their stance towards free trade. Studies in the United States have offered a range of logics that inform such change: a “China shock” had stripped the United States of its manufacturing strength; that China, through its state subsidies and IP theft, had not upheld their end of the free trade bargain and violated WTO rules; and that domestic industrial capacity and technology leadership was essential to national security. The focus of trade policy has now shifted to US–China strategic competition, protecting domestic workers (and voters) and renegotiating existing trade agreements rather than establishing new ones. This logic was again echoed when, in March 2025, the Trump administration released its trade policy agenda, which stressed the importance of a “production economy” centred on the manufacturing industry. The agenda promises a review of existing trade agreements and indicates the Trump administration may go further than Biden-era protectionism for advanced technologies.

This logic was again echoed when, in March 2025, the Trump administration released its trade policy agenda, which stressed the importance of a “production economy” centred on the manufacturing industry. The agenda promises a review of existing trade agreements and indicates the Trump administration may go further than Biden-era protectionism for advanced technologies.

The first Trump administration placed tariffs on China, with the average tariff rate on Chinese imports into the United States rising from three per cent in 2018 to 19% in 2020. These were largely maintained under the Biden administration, while others were tightened, focusing on advanced technologies and clean energy. Notably, Biden’s trade team also took an about-turn on digital trade, withdrawing proposals that protected cross-border data flows, prohibited data localisation requirements and safeguarded US source code from foreign governments. This marked a departure from a 30-year period in which the US government believed American technology companies benefitted from free flows of data — signalling a focus instead on domestic regulation of the technology firms.

Australia has taken a different route to the Trump administration by continuing to promote free trade agreements as essential to its economy.

With Trump back in office since January 2025, tariffs have once again taken centre stage. On 2 April 2025, President Trump proclaimed “Liberation Day”, which included a 10% baseline tariff on all foreign imports (with some exceptions) and a series of ‘reciprocal’ tariffs on countries, dependent on their perceived trade standing with the United States. At the time of writing, the baseline 10% tariff remains in effect, while negotiations continue over the delayed ‘reciprocal’ tariffs. In addition, a range of sectoral tariffs have been implemented (steel and aluminium) and others proposed (copper, timber, critical minerals, semiconductors, and pharmaceuticals). In particular, US tariffs on China have risen sharply, peaking at 145% (since dropped to approximately 50%), meanwhile the US Government has turned to bilateral negotiations to establish trade deals with other countries before a current 9 July deadline for the return of the reciprocal tariff rates.

Australia has taken a different route to the Trump administration by continuing to promote free trade agreements as essential to its economy. Since 2015, Australia has signed seven new bilateral trade agreements and three multilateral trade agreements. Under the first Trump administration changes to trade were limited, with Australia securing an exemption in 2018 from tariffs on steel and aluminium — only the third country after Mexico and Canada to do so.

However, as of July 2025, Australia remains subject to a baseline 10% tariff on all exports to the United States, as well as tariffs on steel and aluminium — unable, to date, to secure an exemption. For the first time since AUSFTA’s creation, Australian exporters face higher US tariffs.

Sectoral agreements: pairing trade with other political priorities

Future trade cooperation between Australia and the United States is likely to focus on supply chain integration and technology regulation. Increasingly, trade policy is focused on the advanced technology and energy industries and issues like supply chain disruptions. Such cooperation could take the form of sector-specific agreements, advocated by the US Trade Representative’s 2025 policy paper on improving US supply chain resilience.

Australia has already signed new sectoral Digital Economy and Green Economy agreements with its long-time free-trade partner Singapore. These centre on R&D cooperation and aligning regulations in the electricity and shipping sectors. Similar sectoral proposals exist for other areas, such as a “Trusted Semiconductor Sectoral Arrangement”, in which a set of close partners facilitate the development of semiconductors throughout the supply chain.

Sectoral trade agreements around technology are likely to become ever-more critical as the technology sector and the software it provides increasingly underpin national economies and security.

Such an approach offers a potential blueprint for future trade agreements, a path forward at a time when traditional trade agreements have fallen out of favour and a method for pairing (limited) trade openness with other government priorities, such as energy or national security. More formal sectoral agreements between Australia and the United States could provide certainty for investors navigating markets increasingly affected by policies enacted by the United States and China. This could include Australia and the United States aligning on issues like local content requirements for defence and energy projects, levels of Chinese investment in critical industries, linking tax incentives or public financing tools.

In particular, sectoral trade agreements around technology are likely to become ever-more critical as the technology sector and the software it provides increasingly underpin national economies and security. This includes addressing the regulation of digital trade — a growing issue with the rise of ecommerce platforms and software-as-a-service and subscription models, which has already raised questions in the context of Australia-US relations when it comes to taxing software-only sales. Addressing pushes for more local technology procurement will be important, alongside building opportunities for fledgling parts of the technology sector — such as in quantum computing — to drive mutually beneficial trade with key partners.

Bilateral free trade agreements like AUSFTA have always been about preferencing — signalling stronger ties with a particular country by reducing barriers to markets. Although the United States is turning away from market access and free trade at present, there are still ways Australia and the United States can move forward, such as through preferential regulations, policies and investment.

Thank you to current and former USSC staff for their

contributions in the development of this piece.