Executive summary

- The US dollar remains the dominant currency for international trade and investment, foreign exchange market turnover and settlements, debt issuance and official foreign exchange reserves held by central banks.

- The role of the US dollar reflects the unrivalled size, depth and liquidity of US dollar capital markets, backed by America’s high quality political and economic institutions.

- Contrary to popular myth, the US dollar’s role owes very little to its status as a so-called "reserve currency." The US dollar share of the world’s foreign currency reserves is a symptom, not a cause, of its dominant role.

- If foreign central banks were to hold less US dollar assets, it would make almost no difference to the US dollar exchange rate or interest rates. China’s holdings of US dollar reserves have no value as an instrument of international economic coercion.

- The role of the US dollar does not depend on a "strong dollar" policy. So long as the US enjoys a floating exchange rate and an independent Federal Reserve continues to target domestic inflation, the United States does not have a meaningful or effective exchange rate policy.

- The US dollar has seen significant cyclical swings in value against other currencies, consistent with the role of a floating exchange rate in moderating economic shocks.

- The US dollar’s potential rivals are beset with problems. The euro is part of a dysfunctional monetary union and its share in the international monetary system has declined over the last 15 years.

- China’s RMB is part of a managed exchange rate regime and a system of capital controls and financial repression that is inconsistent with the RMB achieving international status. The campaign to internationalise the RMB from 2009 has been a failure.

- The US dollar typically strengthens at times of international economic and political stress, highlighting the relative strength of US political and economic institutions.

- The Trump administration’s trade war has strengthened the US dollar exchange rate by around 12 per cent in real terms, exacerbating trade tensions and threatening a protectionist spiral.

- Australia’s bilateral investment relationship with the United States leaves Australia with a net exposure to the US dollar as part of its net foreign currency asset position.

- Australia’s US dollar assets and hedging of US dollar borrowings offset its US dollar liabilities.

- Australia’s net international investment position improves when the Australian dollar depreciates against the US dollar.

- The international role of the US dollar enhances the contribution the bilateral investment relationship with the United States makes to the Australian economy and complements the diplomatic and security relationship.

Introduction

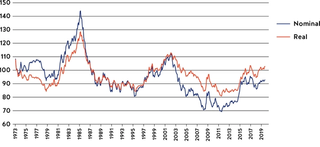

The US dollar exchange rate has become increasingly politicised. President Donald Trump has called for a weaker exchange rate, a move away from a long-standing and bipartisan rhetorical position favouring a "strong dollar". At the same time, US Democratic presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren has called for a managed exchange rate to boost employment and exports,1 while two members of Congress have sponsored a bill that would tax foreign capital inflows into the United States with a view to balancing its external accounts.2 This increased politicisation is partly a symptom of a significant appreciation in the US dollar since President Trump assumed office (Figure 1). As this report will show, this appreciation is not inconsistent with a chaotic trade war and the Federal Reserve cutting interest rates. The US dollar exchange rate often appreciates on increased international political and macroeconomic risk.

The strength of the US dollar exchange rate is often viewed as a measure of the strength of the US economy, at least on a relative basis. However, the US dollar plays a unique role in the global economy that reflects fundamental strengths of the US economy and political system. These strengths are for the most independent of the economic cycle, domestic politics and the ups and downs of exchange rates — although the United States is not immune to concerns about the long-term sustainability of its public finances and the state of its domestic politics.

The sources of the US dollar’s role in the world economy are widely misunderstood, leading many analysts to mistakenly forecast the US dollar’s long-term demise. The global role of the US dollar is not only a function of economics. As Adam Posen has observed, “the United States’ political leadership in security, commercial and even cultural affairs globally has a critical impact on the usage of the dollar in the monetary realm”.3 International economic and security leadership go hand in hand.

Figure 1. US dollar trade-weighted index — major currencies, goods March 1973 = 100

The United States is the premier producer of safe assets that act as stores of value for the world’s savers. Of the US$16.1 trillion in publicly held US Treasury securities, foreigners hold a 39 per cent share. Of that 39 per cent, a 17.9 per cent share is held by mainland China (ex-Hong Kong).4 The demand for these assets from the rest of the world has increased at a faster pace than the United States can produce them because US economic growth has slowed relative to much of the rest of the world. Changes in the regulation of financial institutions and markets since the 2008 financial crisis have increased the quantity of safe assets financial intermediaries are required to hold, subtracting from their liquidity. This increased demand explains why yields on US Treasuries and other countries’ government bonds have been low in recent years. Bond yields are inversely related to bond prices. One way this global excess demand can be satisfied is through an appreciation in the US dollar exchange rate so that US dollar assets become more expensive for those outside the United States.

The structural increase in the demand to hold US dollar safe assets is augmented by cyclical demand during times of economic stress, not least in the United States. Although the financial crisis of 2008 was centred on the US economy, the US dollar exchange rate rose during the crisis (Figure 1) on safe-haven flows because US dollar assets remained a relatively safer bet. More recently, as Prasad notes, "it is striking that, so far during 2019 — amid all the trade wars, geopolitical tensions, and economic and political recriminations against the US — foreign central banks in aggregate have been net purchasers of US Treasury securities."5

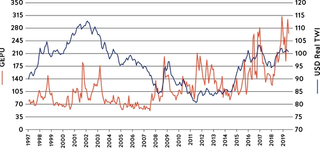

This safe-haven bid for US dollar assets means that the US dollar often behaves in ways that seem counter-intuitive relative to US economic fundamentals. As Figure 2 shows, the US dollar appreciates in response to economic policy uncertainty. A 1 per cent increase in the Global Economic Policy Uncertainty Index raises the real value of the US dollar by 0.2 per cent, controlling for relative interest rate, inflation and economic growth differentials with the rest of the world. The 60 per cent increase in measured economic policy uncertainty under the Trump administration, due to its trade war with the rest of the world, has added around 12 per cent to the real value of the US dollar holding these other influences constant.6 The appreciation exacerbates trade tensions between the United States and the rest of the world by weighing on US export competitiveness, setting in train a protectionist spiral.

Figure 2. Global economic policy uncertainty index and USD trade-weighted index

This report examines the US dollar’s global role and its implications for Australia. The report first looks at the dollar’s global pre-eminence and how this has increased over time, despite many analysts’ predictions to the contrary. The report then examines the role of the US dollar as a "reserve asset", arguing that this reserve asset function is a symptom and not a cause of the dollar’s pre-eminence. While many analysts seek to explain developments in exchange rates and interest rates with reference to changes in reserve asset holdings, it is mostly market-driven changes in exchange rates that drive changes in reserve assets, as central banks adjust their holdings to meet portfolio benchmarks in response to movements in exchange rates. A key implication is that China is unable to effectively ‘weaponise’ its US$1.124 trillion holdings of US Treasuries.

Nor is the role of the US dollar due to a "strong dollar" policy. The US currently has no meaningful exchange rate policy and cannot implement one given an independent Federal Reserve targeting inflation. The ability of policymakers to set an exchange rate independently of market forces for extended periods of time is limited.

The real source of the US dollar’s global role is the unrivalled size, depth and liquidity of US capital markets, backed by high quality political and economic institutions that few countries can match either currently or prospectively.

The real source of the dollar’s global role is the unrivalled size, depth and liquidity of US capital markets, backed by high quality political and economic institutions that few countries can match either currently or prospectively. Other currencies, most notably the euro and the Chinese renminbi (RMB), have the potential to rival the role of the US dollar given the size of their economies, but this would require them to match the strength and openness of US capital markets and the political and economic institutions that underpin them. But both the euro zone and China are beset by chronically weak political and economic institutions that are also resistant to reform. The prospect that either the euro or RMB significantly displace the dollar in the global economy in the medium-term is close to zero.

The report also examines the extent to which the US dollar and other currencies can be "weaponised" as part of a "currency war". While the United States could resort to intervention in foreign exchange markets or a managed exchange rate as part of its trade war with the rest of the world, these efforts would only introduce increased volatility into financial markets, without changing underlying economic fundamentals. However, the dominance of the US dollar in global finance does provide the United States with a potentially powerful instrument of international economic coercion when used to enforce economic and financial sanctions against state and non-state actors.

Finally, the report considers Australia’s relationship to the US dollar. Australia’s bilateral investment relationship with the United States7 leaves Australia with a net exposure to the US dollar as part of its net foreign currency asset position. Australia’s US dollar assets and hedging of US dollar borrowings offset its US dollar liabilities. Australia’s net international investment position improves when the Australian dollar depreciates against the US dollar. Australia’s integration with US dollar-denominated capital markets finances domestic investment and complements our diplomatic and security relationship with the United States. The international role of the US dollar enhances the contribution the bilateral investment relationship makes to the Australian economy.

The dominant role of the US dollar in the world economy

The US dollar was the anchor currency for the global economy in the post-World War Two period. The Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates saw most advanced economies peg their exchange rates to the US dollar, which in turn was pegged to a parity price for gold. The Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s, as the world’s growing demand for US dollars could not be accommodated by the finite gold reserves of the US government.

The global role of the US dollar has only increased since the demise of the Bretton Woods system and the adoption of floating exchange rates by most advanced economies (notwithstanding Europe’s experimentation with managed exchange rate regimes). Yet this increased global role has been accompanied by perennial predictions of the US dollar’s demise.8 "Is the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency drawing to a close?" asked The Economist magazine’s Buttonwood in a 23 November 2004 column headed "The dollar’s demise". The Economist clearly thought so, arguing with characteristic hyperbole that "America has abused the dollar’s reserve-currency role so egregiously that its finances now look more like those of a banana republic than an economic superpower".9 Yet even in the financial crisis of 2008, which was centred on the United States, the US dollar appreciated against other currencies as investors sought relative safety in US assets. When the US economy seemed most at risk, the US dollar was still favoured by investors relative to other currencies.

The Economist is hardly alone in making premature predictions of the US dollar’s long-term demise. Interviewed for the Wall Street Journal in 2006, the soon to be retired Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia Ian Macfarlane observed:

“I have been in so many meetings, from the late ‘90s onwards, where the participants at the meeting identified the US current account as a serious imbalance that had to be remedied, and that if it wasn’t remedied, the US dollar would go into some sort of free fall and people would stop buying US assets,” he wearily responds. “Clearly, it wasn’t happening. Just as it didn’t happen in Australia.”10

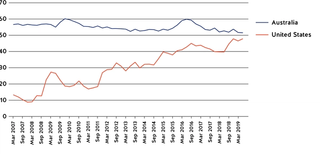

The comparison of the external finances of the United States to Australia’s has, if anything, strengthened over time. As RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle recently noted, “the structure of Australia’s external accounts now resembles that of the United States”.11 Australia’s net foreign liabilities as a share of GDP are now similar to those of the United States (Figure 3), although the United States typically enjoys a higher rate of return on its foreign assets than it pays on its liabilities compared to Australia.

Figure 3. Net foreign liabilities (% GDP)

The long history of failed predictions of the US dollar’s demise reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the US dollar’s role in the world economy. This role is not due to its status as a "reserve currency" or a "strong dollar policy". Nor are the routine cyclical fluctuations in the US dollar exchange rate against other currencies a reliable guide to the US dollar’s international role. A major depreciation in the value of the US dollar against other currencies, if warranted by economic fundamentals, would be perfectly consistent with the US dollar’s continued international pre-eminence, not least because fluctuations in exchange rates help moderate domestic and international economic shocks, enhancing economic resilience. Instead, the importance of the US dollar is a function of the unrivalled size and openness of US capital markets, as well as the prominence of the United States in international trade and investment.

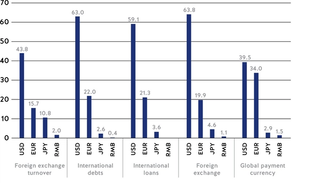

The US dollar is the dominant currency for global debt issuance, invoicing and payments, foreign currency reserves, managed exchange rate regimes, and foreign currency turnover and settlements. (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Share of USD and other currencies in the International Monetary System (%)

The US dollar accounts for 63 per cent of outstanding debt securities globally.12 US capital markets provide a home to much of the world’s saving, ranging from China’s foreign exchange reserves to the retirement savings of Australians. US dollar-denominated debt issuance allows both domestic and foreign companies to tap America’s deep and liquid capital markets. The US dollar capital raised can be more easily spent than funds raised in other currencies. By contrast, the next largest currency of denomination, the euro, accounts for just over 20 per cent of international debt securities on issue.

International trade in goods and services is denominated predominantly in US dollars, with the US dollar accounting for 40 per cent of cross-border financial transactions.13 The Australian dollar ranks seventh with a 1.6 per cent share. The US dollar’s share as an invoicing currency is 4.7 times the share of US goods in world imports and 3.1 times its share in world exports.14 The US dollar dominates turnover in foreign exchange markets, is on one side of 88 per cent of foreign exchange market transactions and accounts for 91 per cent of all foreign exchange settlements.15 Its liquidity means that large US dollar transactions can be conducted without triggering adverse price movements. International US dollar financial transactions are ultimately cleared in the United States by US financial institutions or offshore in dollar-clearing centres that comply with US laws. The world’s financial institutions rely on US banks to access the US dollar payments system, giving the US government and regulators effective control over much of the international payments architecture.

The foreign exchange value of the US dollar is a relative price, and the United States often looks relatively attractive compared to the rest of the world, even when its domestic politics and budgetary process appears dysfunctional.

US-issued currency is demanded as a medium of exchange and store of value not just within the United States, but circulates widely outside US borders. Approximately half of the stock of US currency in circulation is held overseas,16 with estimates ranging between 30 per cent and 65 per cent.17 The $100 bill commands an 80 per cent share of US currency in circulation, suggesting demand is mainly driven by the store of value function.

Many analysts have sought to explain the US dollar’s role in terms of imputed network effects which could be offset or rivalled by an alternative currency, but the evidence for a network effect is weak and is likely trivial compared to the real sources of the US dollar’s role.18 The role of the US dollar in the world economy is a symptom rather than a cause of the fundamental strength of its political and economic institutions, as well as its internationally unrivalled capital markets. The ups and downs of the US economy and politics for the most part do not impinge upon the fundamental soundness of these institutions, a fact often rewarded by international investors. While the US dollar is not immune to concerns about the long-term sustainability of its public finances, the United States is hardly unique in this regard. The outlook for the public finances of many other advanced economies is just as problematic. As some researchers have put it, “the safety of an asset does not depend on the absolute fiscal surplus of a country, but the country’s surplus relative to other countries’ fiscal surplus”.19 The foreign exchange value of the US dollar is a relative price, and the United States often looks relatively attractive compared to the rest of the world, even when its domestic politics and budgetary process appears dysfunctional.

Is the US dollar a ‘reserve currency’?

The US dollar features prominently in the foreign exchange reserves held by the world’s central banks and this is what most people have in mind when they refer to the dollar as a "reserve currency" or "reserve asset". Prasad defines a reserve currency as "typically hard currencies, which are easily available and can be traded freely in global currency markets, that are seen as safe stores of value."20 Prasad does not define what "hard" means in this context. He also implies that inclusion in the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket confers "reserve" status, although IMF SDRs are little more than a unit of account. The economic significance of foreign exchange reserves is rarely explained.

According to the IMF’s Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) data, the US dollar makes up US$6.79 trillion of the world’s US$11 trillion in allocated foreign exchange reserves or around 62 per cent of the total. While this is down from 66 per cent in 2015, Prasad notes that this apparent decrease is an artefact of the transition to more comprehensive reporting by China of its reserve holdings.21 The next most widely held currency is the euro at just 20 per cent. The Australian dollar makes up just under 2 per cent of global official sector currency reserves.22

The world’s central banks hold foreign exchange reserves to give them the capacity to buy and sell their own currency against that of another country. Foreign exchange reserves can also be used by governments to buy and sell foreign goods and services, but official reserves are not necessary for that purpose. The government can always step into the foreign exchange market and buy whatever foreign currency it needs without having to hold reserves. Foreign exchange reserves can hedge against fluctuations in the value of the domestic currency, although to the extent that central banks have a net exposure to foreign currency assets, it also leaves them exposed to valuation or realised losses. Holding foreign exchange reserves is an inefficient form of insurance which could be replaced by risk-sharing arrangements such as central bank swap lines, credit facilities and reserve sharing arrangements.23

Foreign exchange reserves are not essential in the context of a freely floating exchange rate such as Australia’s, where market forces determine the rate at which the domestic currency trades against other currencies. It is only when countries set an official exchange rate independent of market forces or intervene in the market for other purposes that reserves become important.

A fixed exchange rate regime fixes the price of the domestic currency unit against one or more foreign currencies. A managed exchange rate allows this price to fluctuate within a range. A fixed or managed exchange rate is maintained by the central bank intervening in the market to buy or sell the local currency against foreign currencies to maintain a desired rate. Many countries anchor their currency to the US dollar because their trade and investment with the rest of the world is largely US dollar-denominated. Around 70 per cent of countries have the US dollar as their anchor or reference currency.24 In this context, US dollar reserves are essential to managing the exchange rate. Countries linking their exchange rate to the US dollar include all of Latin America, China, most of the rest of Asia, Africa and the former Soviet Union. This linkage is often motivated by foreign policy and security ties to the United States.25

Many countries anchor their currency to the US dollar because their trade and investment with the rest of the world is largely US dollar-denominated.

There has been significant growth in foreign exchange reserves in recent decades. The economies of East Asia in particular sought to rebuild foreign exchange reserves following the Asian crisis of the late 1990s, typically by intervening to lower the value of their exchange rate and boost export competitiveness.26

If the exchange rate is to be held above its market-determined or equilibrium price, the central bank must sell foreign currency reserves in exchange for the domestic currency. The size of these reserves puts a limit on how long the central bank can hold a currency above its market clearing level. If economic fundamentals are driving the exchange rate lower, it may not be possible to maintain a fixed rate because foreign exchange reserves will be exhausted. Exchange rate regimes that seek to hold an exchange rate above its fundamental value eventually succumb to market-driven pressures for devaluation. Markets can also force a revaluation of under-valued exchange rates. The float of the Australian dollar in December 1983 was brought on by market speculation of an official revaluation. Market participants will often accelerate this process by anticipating the change in the official exchange rate, forcing the hand of policymakers. Propping up the value of the exchange rate while holding finite foreign exchange reserves can be an invitation to speculative attack. A floating exchange rate like Australia’s is resistant to speculative attack, because investors have to bet against an efficient market, rather than the actions of policymakers, which are relatively more predictable.

Foreign exchange reserves are not needed to weaken an exchange rate. A central bank can debase the external value of its own currency without limit, subject only to the constraint that this may increase the domestic inflation rate to undesirable levels. The accumulation of foreign reserves is a by-product of a policy of keeping the exchange rate undervalued as the central bank sells its own currency for foreign exchange. China’s US dollar reserves were accumulated during periods in which it was fixing its exchange rate below its fundamental value.

Since the demise of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in the early 1970s, most developed countries have maintained floating exchange rates (Europe’s Exchange Rate Mechanism of the early 1990s was a notable exception) and generally refrained from intervening in foreign exchange markets. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has not intervened in foreign exchange markets for the purpose of influencing the exchange rate or its volatility since 2008. However, central banks of countries with floating exchange rates still typically maintain foreign exchange reserves to give them the capacity to intervene in foreign exchange markets when market-determined exchange rates are excessively volatile, over or under-shooting their assumed equilibrium value or are insufficiently liquid to form a price consistent with fundamentals.

The effectiveness of foreign exchange market intervention is much debated. RBA research finds a small but not very persistent effect from its own interventions.

The effectiveness of foreign exchange market intervention is much debated. RBA research finds a small but not very persistent effect from its own interventions.27 Intervention is more effective when working in the same direction as domestic monetary policy. In that case, it is likely that monetary policy is the stronger influence. Intervention is also more effective when coordinated in a consistent way by multiple central banks. But central bank foreign exchange reserves and balance sheets are small relative to total turnover in foreign exchange markets, which is around US$6.6 trillion daily.28 As the historical demise of many exchange rate regimes suggests, central banks have only a limited ability to set an exchange rate independent of market forces in the medium to long-run.

For currencies that lack well-established and liquid foreign exchange markets, trading against non-US dollar currencies is typically done indirectly via US dollars to take advantage of the depth and liquidity of markets for US dollar assets. This creates a demand for US dollars even for transactions otherwise denominated in other currencies. However, this has little to do with "reserve currency" status.

There is a small benefit that flows to the United States from the fact that foreign central banks hold its currency. It costs virtually nothing for the United States to produce a unit of domestic currency, but foreign central banks pay the face value of the currency when acquiring US dollar reserves. The economic costs of supplying and holding official reserve assets is a function of relative rates of return on reserves compared to domestic assets, which is determined by interest rate differentials and exchange rate movements.

There is another benefit that flows to the United States from the widespread use of the US dollar for international trade and investment. The United States typically imports and borrows in its own currency and so is less exposed to the exchange rate changing the value of its imports and external liabilities, facilitating its ability to borrow internationally. The ability of the United States to borrow in its own currency was famously dubbed an "exorbitant privilege" by a French finance minister in the 1960s. This exorbitant privilege is considered one of the main benefits of "reserve currency" status, but it has little to do with the official reserves held by foreign central banks. It is a function of the size and depth of US dollar capital markets and the desire of foreigners to invest in US dollar assets.

The international role of the US dollar does not depend on other central banks holding US dollar reserves. Instead, these reserves are a reflection of the international role of the dollar.

The ability to borrow in US dollars and its role in sustaining international net debtor status is exaggerated. Australia has traditionally borrowed more heavily internationally than the United States as a share of GDP, but the exchange rate risk is either offset by foreign currency assets or hedged back into Australian dollars. Australian interest rates have typically been higher than those in the United States, possibly reflecting risk premia derived from the size of Australia’s net foreign borrowing, but this risk premium has not impeded Australia’s ability to access international capital markets relative to the United States. The net foreign liabilities of the United States are now little different from Australia’s and Australia’s interest rates are below those in the United States, albeit for largely cyclical reasons.

Foreign exchange reserves were important in the context of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange system that prevailed until the early 1970s and still play an important role for those countries that fix or manage their exchange rates, such as China. But these reserves play only a small role for the majority of developed countries that allow their exchange rates to be determined by market forces, including Australia and the United States. The international role of the US dollar does not depend on other central banks holding US dollar reserves. Instead, these reserves are a reflection of the international role of the dollar.

Do official sector foreign exchange reserves matter for exchange rates and interest rates?

Do changes in the composition of official sector (mainly central bank) holdings of foreign currency assets matter for exchange rate or interest rates? Some financial markets participants pay considerable attention to changes in the reserve holdings of central banks and other government institutions such as sovereign wealth funds. Analysts pour over the US Treasury’s Treasury International Capital (TIC) system data looking at changes in reserve holdings with a view to understanding their implications for exchange rates and interest rates. This is understandable to the extent that banks want to capture the business of executing trades on behalf of governments and other official sector clients. But these transactions are of limited economic significance. Those who look to changes in official reserve assets as a guide to future movements in financial market prices are bound to be disappointed.

Do changes in the composition of official sector (mainly central bank) holdings of foreign currency assets matter for exchange rate or interest rates?

Central banks typically have fixed target allocations or benchmarks for their holdings of given currencies in their foreign exchange reserves and rebalance those portfolios in response to movements in exchange rates. This means they will buy more of a currency that depreciates in value and sell a currency than appreciates in value. Suggestions central banks might reduce their US dollar reserves in response to a US dollar depreciation, exacerbating the depreciation, have things exactly backwards. As Posen notes, “there is no simple relationship between even sustained movements in exchange rates and reserve shares”.29

Former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan has written persuasively about the irrelevance of changes in official sector reserves to exchange rates and interest rates. In his autobiography, The Age of Turbulence, he notes that because of the depth and liquidity of US asset markets, “large accumulations or liquidations of US Treasuries can be made with only modest effects on interest rates. The same holds true for exchange rates.”30 Greenspan cites one prominent example:

Japanese monetary authorities, after having accumulated nearly $40 billion a month of foreign exchange, predominantly in US Treasuries, between the summer of 2003 and early 2004, abruptly ended that practice in March 2004. Yet it is difficult to find significant traces of that abrupt change in either the prices of the US Treasury ten-year note or the dollar-yen exchange rate. Earlier, Japanese authorities purchased $20 billion of US Treasuries in one day, with little result.31

If foreign central banks, such as the People’s Bank of China, significantly reduced their US dollar reserves, it would be unlikely to impact either the US dollar exchange rate or interest rates. Changes in the composition of foreign exchange reserves reflect exchange rates more than exchange rates reflect changes in reserves due to valuation effects from exchange rate movements and rebalancing of portfolios in response to these valuation changes.

Does the United States have a ‘strong dollar’ policy?

The US government has formally held to a strong dollar policy since January 1995, when then US Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin first articulated it and the US dollar exchange rate was posting what were then record lows for the post-World War Two period. According to Barack Obama’s Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew, “a strong dollar has always been a good thing for the United States’”. The policy has persisted for more than 20 years and through big multi-year swings in the US dollar exchange rate, swings that have somewhat belied the policy. Since the demise of Bretton Woods, notwithstanding the 1985 Plaza Accord and the 1987 Louvre Accord, the United States has effectively had no exchange rate policy other than at a rhetorical level. Ironically, Rubin would subsequently lose more than US$1 million of his own money betting against the policy by shorting the dollar against other currencies around 2004.32

For US policymakers, the "strong dollar" policy has been something of a rhetorical trap. They feared that if the United States were to formally step-away from the commitment, the US dollar would plunge, perhaps precipitously. George Bush’s Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill recalls how, “I was not supposed to say anything but "strong dollar, strong dollar". I argued then and would argue now that the idea of a strong-dollar policy is a vacuous notion”.33 Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland economists have called the policy the “yeti of economics. Despite occasional sightings… scientific evidence indicates that no such species exists”.34 If US policymakers do not believe in the strong dollar policy, it is unlikely financial markets do either.

While President Trump has shifted US official rhetoric by signalling a preference for a weaker exchange rate to boost US export competitiveness, this preference means little without backing from Federal Reserve policy.

In contrast to previous administrations, President Trump has expressed a preference for a weaker dollar, believing the US dollar exchange rate and foreign monetary policy is to blame for US trade imbalances with the rest of the world. Yet Trump’s shift away from the policy has seen the US dollar appreciate, demonstrating the relative power of economic fundamentals over official rhetoric in determining exchange rates.

Economists have long recognised what has come to be known as the "impossible trinity", which says that it is not possible to maintain a fixed exchange rate, an open capital account and an independent monetary policy. A strong dollar policy falls short of a fixed exchange rate regime, but is still incompatible with an independent domestic monetary policy, especially if monetary policy targets domestic inflation. As Craig and Humpage put it, “either the Fed achieves its exchange rate goal at the expense of its inflation objective, or the exchange rate target is irrelevant because maintaining the inflation objective also promotes the exchange rate goal”.35 The Trump administration could undermine the independence of the Federal Reserve with a view to lowering the exchange rate, but the subsequent rise in domestic inflation would only undermine US competitiveness. The only other policy instrument the Federal Reserve and Treasury have to influence the exchange rate is intervention in the foreign exchange market. But for this to be effective, domestic monetary policy would need to accommodate the intervention, compromising the pursuit of the inflation target.

Can other currencies rival the role of the US dollar?

Both the euro and the Chinese RMB have the potential to increase their respective shares as currencies of denomination for international trade and investment. The RMB is widely expected to grow in prominence as China’s share of global output increases. Similar expectations were once held for the euro. However, neither the euro nor RMB are likely to displace the US dollar in the foreseeable future due to critical weaknesses in their economic and political institutions and financial markets relative to those of the United States.

The advent of the single European currency in 1999 was hailed by many as a boost to the status of European economies and it was widely expected that the euro would come to rival the US dollar in "reserve" currency status and its use in international trade and investment.36 Yet far from being a source of economic strength, the single currency crippled many member economies by locking them into a one-size-fits-all monetary policy. The euro has been a source of economic weakness rather than strength for member economies by limiting the scope for exchange rate adjustment to act as a macroeconomic shock absorber. Europe’s sovereign debt markets remain fragmented and euro-denominated assets are not seen as a safe-haven given the risks inherent in a monetary union not backed by a fiscal or banking sector union.

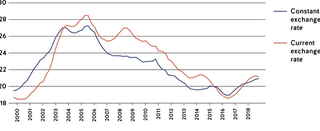

Between 2012 and 2019, the euro’s share of global payments fell 10 percentage points, from 44 per cent to 34 per cent, based on SWIFT data.37 The European Central Bank’s composite index of the international role of the euro shows a decline in the euro’s share in the international monetary system over the 10 years to 2016 (Figure 5). Despite an initial rise, there has been almost no net change in the international role of the euro since its inception in 1999.

Figure 5. Composite index of the international role of the euro (percentages; at current and Q4 2018 exchange rates; four-quarter moving averages)

China mounted a campaign to internationalise the RMB from 2009 onwards, with a particular focus on having the RMB included in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights basket. The RMB was included from 1 October 2016, but this was largely a vanity project, given IMF SDRs are little used other than as a reserve asset or reference rate. The campaign to include the RMB in the SDR basket was partly intended to provide China’s reformers with increased leverage to promote domestic financial liberalisation. However, at the first signs of financial volatility, the Communist Party backed away from financial liberalisation and the campaign to internationalise the RMB lost momentum.38 Standard Chartered’s RMB Globalisation Index has flatlined since September 2015,39 a symptom of the lack of progress in internationalising the RMB.

China’s managed exchange rate regime and capital controls limit its international acceptability. The RMB was fixed with respect to the US dollar from the mid-1990s until July 2005, but has been more flexible since then. In August 2015, China sought to introduce a more market-based approach to setting the RMB’s value, accompanied by a 2 per cent devaluation. But Chinese policymakers were unhappy with the resulting volatility, which they associate with disorder, and quickly reverted to a more managed approach in January 2016.40 Most of China’s international trade remains US dollar denominated. China’s capital markets remain under-developed and are not fully accessible to international investors. RMB-denominated assets are seen as bearing significant macroeconomic and political risks and China’s under-developed capital markets limit the ability of investors to effectively manage those risks.

For China to successfully internationalise the RMB, it would need to give-up much of the apparatus of state control over cross-border transactions and liberalise its financial markets. China once showed signs of moving in this direction, but with the rise of President Xi from 2012 onwards, the Chinese Communist Party has prioritised state control over the economy at the expense of economic reform. While China has liberalised its financial markets at the margin in recent years, the RMB’s international role will remain limited in the absence of full liberalisation.

It should be noted that Japan’s Ministry of Finance presided over a campaign to internationalise the yen in the 1990s, culminating in an ill-fated proposal to establish an Asian Monetary Fund that excluded the United States. It is difficult to see China succeeding where Japan failed.

Both the euro zone and China demonstrate that size alone will not propel a currency to greater international status. The Australian dollar and Swiss franc command larger shares of global foreign exchange turnover than the RMB. Only well-developed capital markets, backed by sound political institutions, relatively sound monetary and fiscal policy, property rights and the rule of law, can provide the underpinnings for a currency that is widely demanded outside its own borders. As one journalist has suggested, “I’ll believe that the yuan is going to be an international currency when an overthrown autocrat’s bathroom wall turns out to be filled with 100 RMB notes”.41

Non-state currencies as a rival to the US dollar

Non-state-backed media of exchange, such as Bitcoin and Facebook’s proposed Libra may well develop to the point where they displace the role of sovereign currencies in domestic and international transactions, including the US dollar. However, it is more likely that these cryptocurrencies will displace those currencies lacking domestic and international acceptability and subject to capital and other controls before displacing the US dollar. The US dollar is likely to remain the principal benchmark against which cryptocurrencies are priced or backed. Competition from these alternative currencies may serve as a discipline on their state-issued counterparts, although these currencies could also come to be regulated in ways that prevent them from effectively competing with the state as the dominant issuer of currency.

Can the US dollar be weaponised as part of a ‘currency war’?

Government intervention in foreign exchange markets, either on an ad hoc basis, or as part of a managed exchange rate regime, could be used to engineer a depreciation of the exchange rate for purposes of making exports more competitive, at least in the short-run. This is known as "beggar-thy-neighbour" exchange rate depreciation or a "currency war". The dominant role of the US dollar in the world economy and the numerous economies that link to the US dollar means that US monetary policy has significant international spillovers. Tighter US monetary policy has a depressing effect on the world economy and international trade and vice versa due to the US dollar’s role as an anchor or reference currency for much of the rest of the world.

It should be noted that market-led exchange rate depreciation due to changes in domestic monetary policy in pursuit of domestic economic stabilisation objectives should not be viewed as predatory towards foreign countries or part of a "currency war". While changes in domestic monetary policy may have international spillovers, countries with floating exchange rates and independent, inflation targeting central banks like Australia have no reason to be concerned that another economy’s domestic monetary policy will put them at a disadvantage. They are always free to adjust their own policies to offset these international spillovers.

It is not surprising that exchange rate policy has been caught-up in the US-China trade dispute. However, for all the talk of a ‘currency war’, exchange rates are difficult to weaponise.

When the Australian dollar rose to record highs in 2011, some commentators suggested that Australia was a victim of monetary easing in other economies, losing international economic competitiveness. But in the context of a terms of trade boom, the appreciation of the Australian dollar served to moderate the impact of higher export prices on the Australian economy. Australia was in no sense a victim of foreign monetary policy. The Reserve Bank of Australia eased its own monetary policy from November 2011 and the Australian dollar exchange rate has depreciated significantly since then.

Global financial markets have recently been unsettled by claims China has devalued its currency against the US dollar, with the US Treasury responding by designating China a "currency manipulator".42 It is not surprising that exchange rate policy has been caught-up in the US-China trade dispute. However, for all the talk of a "currency war", exchange rates are difficult to weaponise.

The best gauge of whether a currency is being manipulated is the magnitude of official intervention in the foreign exchange market and the resulting change in foreign exchange reserves. A fixed exchange rate often requires heavy intervention to maintain it against market forces, which is why the United States labelled China a "currency manipulator" in the mid-1990s, but the label has become an increasingly poor fit for China.

It is difficult to argue that China’s currency has been systematically undervalued in a manner designed to boost its exports. In recent years, China has been intervening to support the value of the RMB to stem capital flight. China’s recent management of its exchange rate is designed to accommodate market forces pushing the exchange rate lower in response to the trade war, while maintaining capital controls and promoting domestic economic stability. If China enjoyed a floating exchange rate like Australia’s, there is little doubt financial markets would have taken its exchange rate lower, perhaps dramatically so, in response to the growing trade war with the United States. Far from intervening to devalue the RMB, the Chinese are simply doing less to stand in the way of a market-led adjustment.

The US government has traditionally advocated flexible exchange rates because they are more consistent with free and open international trade. But under the Trump administration, the United States has sought commitments from China that it will not allow its exchange rate to depreciate as part of any trade deal. The United States is asking China to manipulate its exchange rate in US interests.

Under the Trump administration, the United States has sought commitments from China that it will not allow its exchange rate to depreciate as part of any trade deal. The United States is asking China to manipulate its exchange rate in US interests.

US legislation provides for its Treasury to designate countries as "currency manipulators". The criteria for manipulation are (1) a significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States; (2) a material current account surplus; and (3) persistent one-sided intervention in the foreign exchange market. In fact, the first two criteria are not necessarily inconsistent with a floating exchange rate entirely determined by market forces. Only (3) is a reliable indicator of manipulation. While China satisfies (1), it does not satisfy (2) or (3). Having ignored its own criteria, there is every reason to believe the US Treasury acted politically in declaring China a manipulator. Designating another country a manipulator has no implications under US law other than requiring Treasury to enter into consultations, either bilaterally or through the International Monetary Fund.

While the US Treasury could intervene in foreign exchange markets, with or without the Federal Reserve, such intervention would have little lasting effect and leave the United States itself vulnerable to the charge of manipulation. The United States has deep and liquid foreign exchange and capital markets that are a key economic strength, not least because they are a bulwark against attempts by the US or foreign governments to manipulate exchange rates and interest rates. Attempts to set exchange rates and interest rates at odds with economic fundamentals ultimately fail. Fixed exchange rate regimes eventually succumb to market forces (the Hong Kong dollar being a notable exception to date).43 Managed exchange rates like China’s only succeed to the extent that they accommodate those forces. Floating exchange rates like Australia’s accommodate market forces in real time.

A "currency war" may give rise to increased volatility in financial markets, but lacks effective weapons and won’t change underlying economic fundamentals. Even if the Trump administration could engineer a substantial depreciation in the US dollar exchange rate independently of domestic monetary policy, this would put upward pressure on domestic inflation and undermine US economic competitiveness. Exchange rate policy is not the free lunch President Trump seems to assume.

The US dollar as a foreign policy instrument

The role of the US dollar in international transactions and the US government’s effective control over the infrastructure for the clearing and settlement of US dollar payments gives the United States a potentially powerful instrument for international economic coercion. The US government can use its jurisdiction over the US dollar payments system to enforce compliance with economic sanctions against its adversaries. Russia, Iran, Venezuela and North Korea have been the subject of sanctions whose enforcement is made effective largely by the role of the US dollar in the global economy.

US economic sanctions have considerable reach because both US and non-US financial institutions are reluctant to deal with sanctioned entities and countries for fear of being either fined by US regulators or denied access to the US dollar payments system. Non-US banks rely on their relationships with US banks and their access to US-regulated dollar payments system infrastructure to effect international transactions on behalf of their clients.

The international role of the dollar is a powerful instrument of US foreign policy, but this role does not depend on the exchange rate, "reserve currency" status, or exchange rate policy. Recently, there have been efforts by other countries to develop alternative international payments mechanisms to reduce exposure to US control over dollar payments. For example, Europe has made moves in the direction of pricing oil imports in euros and has created new vehicles to facilitate transactions with Iran to circumvent US sanctions.44 If the US government were to abuse the role of the dollar as an instrument of international economic coercion, it might further foster the development of alternative, non-US dollar-based payments mechanisms. There is therefore some discipline on the use of the US dollar to promote foreign policy objectives, but for now it remains a powerful instrument of international economic coercion.

Australia and the US dollar

Most of Australia’s international economic interactions have the US dollar on at least one side of the transaction. Australia has a net exposure to the US dollar through its deep investment relationship with the United States.45 Australia’s financial markets are closely integrated with US dollar-denominated capital markets, underpinning domestic investment and complementing our diplomatic and security relationship with the United States. Australia thus has a continued interest in the future of the US dollar.

Transactions against the US dollar make up nearly half of the total turnover in Australia’s foreign exchange market (Table 1). The turnover in the Australian dollar in the local foreign exchange market is less than half that of the US dollar.46

Australia’s financial markets are closely integrated with US dollar-denominated capital markets, underpinning domestic investment and complementing our diplomatic and security relationship with the United States.

Australia’s borrowing and investments abroad, predominantly with the United States, leaves the Australian economy with a net exposure of A$217.1 billion to the US dollar when last surveyed in 2017. This consists of A$494.4 billion in US dollar equity assets, A$672.2 billion in US dollar debt assets, offset by A$949.5 billion in US dollar debt liabilities (Table 2).

Australia thus has a net exposure to the value of the US dollar that is a significant share of Australia’s overall net foreign currency asset position. Australia’s US dollar assets effectively offset its US dollar borrowings. When the Australian dollar depreciates, its net foreign liabilities are reduced. The RBA estimates that a 10 per cent depreciation in the Australian dollar reduces net foreign liabilities by around 3 per cent of GDP,47 although this effect will vary with the composition of Australia’s net international investment position. This is a significant change from earlier decades, when a depreciation of the exchange rate would have increased those liabilities.

Australia’s foreign liabilities are overwhelmingly denominated in Australian dollars. Foreign equity liabilities are denominated in Australian dollars. Government debt is issued entirely in Australian dollar terms. The private sector issues foreign currency debt, including US dollar-denominated debt, but these foreign currency debt liabilities are frequently swapped back into Australian dollars. For example, almost all of the Australian banking sector’s net foreign currency exposure is hedged back into Australian dollars.48 After hedging, 85 per cent of Australia’s foreign liabilities are Australian dollar denominated.49 While this process of swapping foreign currency exposures back into Australian dollars is not costless, it means Australia enjoys the benefits of borrowing in international capital markets without taking on excessive exchange rate risk. The "exorbitant privilege" the United States is said to enjoy from borrowing in its own currency is probably overstated given that Australia also effectively borrows in its own currency.

Australia also derives a benefit from the fact that global commodity prices are generally quoted and traded in US dollars. When the US dollar exchange rate appreciates, the US dollar price of commodities fall. Because the value of the Australian dollar exchange rate moves in the same direction as global commodity prices, commodity price shocks, including oil price shocks, are relatively muted in Australian dollar terms.

The Reserve Bank of Australia held A$26.159 billion in US dollar assets or 55 per cent of its A$47.636 billion in net foreign currency assets as at 30 June 2018.50 This is somewhat less than the 62 per cent share of the US dollar in foreign currency reserves globally. The Future Fund also has a significant net exposure to foreign currency assets of A$85 billion, including the US dollar. With Australian interest rates now below those in the United States, the official sector earns a positive interest rate spread on its US dollar assets, although on average, Australian dollar assets have relatively higher yields compared to other developed economies.

The ‘exorbitant privilege’ the United States is said to enjoy from borrowing in its own currency is probably overstated given that Australia also effectively borrows in its own currency.

Former Treasurer Joe Hockey made an A$8.8 billion injection of funds into the Reserve Bank of Australia’s Reserve Fund. The purpose of the Reserve Fund is to cover potential valuation losses on the RBA’s foreign exchange reserves. The Australian government could recapitalise the Bank at any time to cover any losses. However, the Reserve Fund avoids the embarrassment of the RBA having to go cap in hand to the government for a top-up to cover valuation or actual losses at politically inconvenient times.

In announcing the decision, Hockey declared the Bank needed “all the ammunition in the guns for what’s before us”.51 The government’s 2013 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook stated that the injection “will enhance the Reserve Bank’s capacity to conduct its monetary policy and foreign exchange operations”. But as noted previously, foreign exchange reserves are not essential to the conduct of monetary policy. Hockey’s language suggests the then treasurer saw the injection as supporting the Reserve Bank’s capacity to intervene in foreign exchange markets to support the value of the Australian dollar, since foreign exchange reserves are not necessary to weaken the currency.

There is still a rationale for intervention to support foreign exchange market liquidity in times of market stress. Given that the US dollar is the most liquid currency globally and is on one side of nearly half of the foreign exchange transactions in the Australian market, there is a strong case for the Reserve Bank to retain the majority of reserves in US dollars. There is little policy benefit to diversifying these reserves into less liquid currencies, even if diversification gives rise to a portfolio of foreign currency assets that has superior risk-return characteristics. Given that foreign currency reserves are held for policy purposes, the risk-return characteristics of the portfolio should be a second-order consideration compared to supporting the capacity to intervene effectively in foreign exchange markets. But as noted previously, expectations for the effectiveness of any intervention should be low given that its effects are not very persistent.

Conclusion

The US dollar remains the dominant currency for international trade and investment, foreign exchange market turnover and settlements, debt issuance and official foreign exchange reserves. The dominant role of the US dollar in the world economy reflects the unrivalled depth and liquidity of US dollar capital markets, backed by America’s high quality political and economic institutions.

Contrary to popular myth, the US dollar’s role owes very little to its status as a so-called "reserve currency". The fact that the US dollar makes up most of the world’s official foreign currency assets is a symptom, not a cause, of the US dollar’s dominant role. If foreign central banks were to hold less US dollar assets, it would make almost no difference to the US dollar exchange rate or interest rates.

Nor does the role of the US dollar depend on a "strong dollar" policy. So long as the US enjoys a floating exchange rate and an independent Federal Reserve continues to target domestic inflation, the US does not have a meaningful or effective dollar policy. While President Trump has shifted US official rhetoric by signalling a preference for a weaker exchange rate to boost US export competitiveness, this preference means little without backing from Federal Reserve policy. The US Treasury, with or without the support of the US Federal Reserve, could intervene in foreign exchange markets with a view to influencing the value of the exchange rate. However, such intervention would have little to no sustained effect on the US dollar exchange rate and would do little to change US export competitiveness. Such intervention would only serve to increase foreign exchange market volatility. For all the talk of "currency wars", exchange rates are difficult to weaponise.

The role of the US dollar also does not depend on its relative strength against other currencies. The US dollar has seen significant cyclical swings in value against other currencies, consistent with the role of a floating exchange rate in intermediating foreign and domestic economic shocks. Perennial predictions of the US dollar’s demise as the dominant international currency have not been borne out because they misunderstand the sources of the US dollar’s role or because they wrongly assume that a decline in the US dollar exchange rate is inconsistent with its role as the world’s dominant currency.

In principle, the US dollar’s role could be supplanted by other currencies. But the US dollar’s nearest potential are beset with problems.

In principle, the US dollar’s role could be supplanted by other currencies. But the US dollar’s nearest potential are beset with problems. The euro is part of a dysfunctional monetary union that has impoverished some member economies, while enriching others, given rise to political and diplomatic tensions that are tearing the European Union apart. China’s RMB is part of a managed exchange rate regime and a system of capital controls and financial repression that is inconsistent with the RMB achieving international status. RMB-denominated assets suffer from poor quality governance, insecure property rights and a non-existent rule of law. Cryptocurrencies may challenge the role of fiat currencies, but are more likely to displace less dominant currencies before displacing the US dollar. The US dollar is likely to remain the principal benchmark against which cryptocurrencies are priced.

The US dollar typically strengthens at times of international economic and political stress, highlighting the relative strength of US political and economic institutions. This remains the case, even as President Trump has unleashed a chaotic trade war against the rest of the world. While there is some evidence that domestic political partisanship undermines the safe-haven appeal of the US dollar,52 the US dollar’s international role is unlikely to be significantly diminished by the Trump administration and could be reinforced, even if for perverse reasons. The policy uncertainty associated with President Trump’s trade war has led to a 12 per cent appreciation in the US dollar in real terms, exacerbating trade tensions.

Australia’s deep bilateral investment relationship with the United States leaves Australia with a significant exposure to the US dollar. Australia’s US dollar assets offset its US dollar liabilities. Australia’s net international investment position improves when the Australian dollar depreciates against the US dollar. The integration of Australian and US capital markets ensures that Australia can access the world’s largest, deepest and most liquid market for capital, underpinning domestic investment and economic growth. The international role of the US dollar enhances the contribution the bilateral investment relationship with the United States makes to the Australian economy and complements the diplomatic and security relationship.