Dave Chappelle’s latest special, 8:46, was released via YouTube less than two weeks after George Floyd was killed. Held outdoors, with socially-distanced seating and an audience wearing “Chappelle”-branded face masks, it was the first North American concert since COVID-19 started ravaging the United States. “Like it or not, it’s history,” he says to the audience, “it’s going to be in the books.” It is also a monument to the time captured in the title.

Chappelle has used his comedy to interrogate the destructive consequences of racism and inequality in the United States for decades, but he cannot fathom how one person can so casually murder another person over a protracted 8 minutes and 46 seconds. It’s the hand in the pocket of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin as he knelt on Floyd’s neck that so rankles Chappelle. “Who are you talking to?!” he demands. “What are you signifying?!” The comedian’s sensibility, like a psychoanalyst’s, finds the perverse detail that precariously stitches together the tragedy. But this is not humour as therapy or catharsis, working through the trauma to get past it. You should emerge wounded and spooked. Unlike a psychoanalyst, Chappelle gets “wrath-of-God” mad and rips the seam so it unravels into comedy — bursting an individual event into the social, national, and global. The “streets are speaking,” Chappelle declares, because hundreds of thousands of people have responded in the same way as Chappelle. Here, in Australia, thousands have been spurred to protest the hundreds of indigenous deaths in custody that have yet to result in a single conviction. Defying directives from government, and educating us about our own history of slavery, the streets demanding that black lives matter everywhere.

Chappelle’s special is stand-up comedy in the sense that a comedian stands alone on a stage, with a microphone, in front of an audience, and speaks. But most of what he says is not funny; it is a sick joke.

Chappelle’s special is stand-up comedy in the sense that a comedian stands alone on a stage, with a microphone, in front of an audience, and speaks. But most of what he says is not funny; it is a sick joke. As an American Studies lecturer, my automatic response might be to place Chappelle in the tradition of American humourists “speaking truth to power.” I may perhaps cite “The Great American Joke” described by literary scholar Louis D Rubin, Jr in The Comic Imagination of American Literature as, “the gap between the ideal promise of American democracy—freedom, equality, self-government—and the ordinary quality of everyday life.”

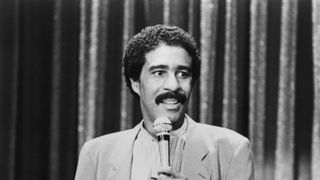

But 8.46 is more specific. More appropriate and instructive than hoary bromides about the essential role of humour is historicising 8.46 within the lineage of black comedians who have confronted racist violence. Many of us would do well to listen and learn from this heritage — you might even laugh now and then. Back in the early 1960s, Dick Gregory became one of the first Black comedians to cross over from the Black comedy circuit. Gregory mercilessly examined US race relations on stage, saying he had one intention in performing: “I didn’t come here tonight to impress you, only to inform you.” He became very active in the civil rights movement, speaking at Selma, Alabama, in 1963, before the voter registration drive. His vocal stance against the Vietnam War led the Gorton government to deny him entry to Australia in 1970.

Richard Pryor, who became prominent in the 1970s and is regarded by many as the greatest stand-up of all time, assumed Gregory’s mantle in his own way. This comparison proves most useful. There is the haunting specificity with which Pryor confronted racism and police brutality — he discussed police chokeholds in his 1979 special, and pointed to capitalism as the prime mover of division and conflict in the world in a 1977 television interview with Bill Bloggs. Pryor was also uniquely vulnerable on stage, letting us in so we could all gather on a common ground of fear: of others, of ourselves and of who and what rules us. Chappelle acknowledges his own misogyny and transphobia, even as he plays it for laughs. When five police officers were killed during a Black Lives Matter protest in Dallas in 2016, he admits to fearing for his family’s safety and contemplating leaving the United States. You can choose to join him, or not. There are no purity tests here. Just a demand for truth.

The “streets are speaking now,” and Chappelle says he’s “happy in the back seat.” But he’ll be a back-seat driver of sorts, delivering an intensely personal history lesson that, in drawing in an audience of over 25 million. A voice suggesting direction and purpose as others lead, he articulates generational pain and infuriatingly familiar outrage around the pernicious persistence of racist violence. Chappelle narrates the call that the murder of George Floyd peals out, answering a question that should not need asking. Four hundred police officers turned up to capture (and ultimately kill) cop-turned-cop killer Christopher Dorner because one of their own had been murdered. That is precisely what is happening now, says Chappelle, addressing the police and the state, “We saw ourselves like you see yourself.”

Four hundred police officers turned up to capture (and ultimately kill) cop-turned-cop killer Christopher Dorner because one of their own had been murdered. That is precisely what is happening now, says Chappelle.

There is no mention of either President Trump or the Democrats. Both have acted in hollow symbolic ways since Floyd’s death, performing morality plays they hope pass for action. One blasts a path through American citizens (and Australian media) with tear gas and batons to pose with a Bible in front of a church; the others kneel in kinte cloth for 8 minutes and 46 seconds with unclear motives beyond barest alliance. This reality would be judged too on-the-nose if Chappelle were writing a joke; “Breonna’s Law,” which bans no-knock warrants, was passed in Louisville, but no-one has been charged for the shooting of Breonna Taylor, who was killed when Louisville Metro police officers executed such a warrant. The perversity of Trump’s photo op is obvious, brandishing what American Studies scholar George Lipsitz might call “the possessive investment in whiteness”, here vouchsafed by religion. The puzzling emptiness of the Democrats kneeling begs the question: Who is writing this stuff? Why would re-enacting the death of a man at the hands of the state, by those who wish to govern, augur anything positive? You would have to cite the wilfully ignorant furore around Colin Kaepernick taking a knee to give them a pass.

Instead, Chappelle gets to a central issue: trust. We want to hear from him because he won’t lie to us. All our other institutions, he notes, lie. Government, police, media, universities, workplaces: everyone has been on the end of institutional deceit, obfuscation or about-faces, none of which has been to the advantage of those beholden to these institutions, and all of which has been unavoidably laid bare by COVID-19. The space where the jokester tells you a truth, where you “get” the joke, whether it be outdoors during a global pandemic, or before a screen where you stream the special, creates a community that Chappelle notes is “the last stronghold for civil discourse.” After this, as Chappelle closes out 8.46, “it’s just ratatat-tattatitee-tatat-tatat!”