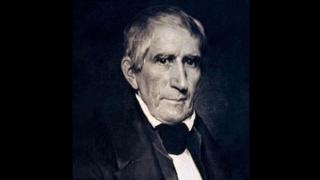

William Henry Harrison is largely remembered for one fact in his presidential career. Elected in November 1840, at the age of 68, Harrison is the shortest-serving US president, holding office for only 31 days. He died after contracting pneumonia in the rainy, fever swamp that was then Washington, DC.

Harrison was undoubtedly a war hero, serving in the frontier wars and in the War of 1812 against Britain. He was most famous for his victory at the Tippecanoe River in Indiana in 1811.

Retired to his farm in Ohio, Harrison was recalled to duty by the Whig Party as its presidential candidate to oppose incumbent Democratic president Martin Van Buren. The Whig campaign of that year changed US presidential politics, and its excesses and flourishes are still evident today.

The Whigs claimed Harrison lived in a humble log cabin. Actually, the log cabin had long ago been subsumed in the family mansion. Hard cider was supposed to be the venerable general’s favourite drink. This was also a considerable exaggeration. But it laid the groundwork for creating an image of a man whose sense of duty outweighed his sense of ambition, given the modesty of his supposed lifestyle.

Tyler was something of an embarrassment as president, fighting with his party to the extent that most of his cabinet resigned and much of the Whig Party in congress wanted to impeach him.

The Whig slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too”, often was painted on the roofs and walls of mobile log cabins that were the centrepieces of campaign parades, along with symbols of the Republic such as bears and eagles. The parades usually involved thousands of people and stretched for kilometres. They remain enshrined in American presidential displays to this day.

Tyler in the slogan refers to Harrison’s vice-presidential running mate, John Tyler, a slave-owning senator from Virginia.

Tyler was something of an embarrassment as president, fighting with his party to the extent that most of his cabinet resigned and much of the Whig Party in congress wanted to impeach him. He identified with the slave power at the outbreak of the American civil war, ending his days as a congressman in the Confederate House of Representatives in Richmond.

The 1840 presidential campaign is examined in enlightening detail by Ronald Shafer, once a journalist with The Wall Street Journal, in The Carnival Campaign: How the Rollicking 1840 Campaign of “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” Changed Presidential Elections Forever.

Until the 1840 campaign, it was thought unusual if not improper for presidential candidates to campaign themselves. Surrogates usually spoke for the candidates. Newspapers did the heavy lifting and pamphlets were the equivalent of social media. Harrison changed that, engaging in a run of speeches out in Ohio and elsewhere that dominated the news but also served to exhaust him, a salient pointer to the future.

The Whig press was enthusiastic about Harrison’s robust performances, while the Democrats were dismissive. By the way, the history of the American press from the 1790s was to be overtly partisan, in support of candidates and parties, rather than being journals of record. Two examples will suffice.

The Ohio Statesman delivered this judgment on Harrison: “(The Whig nominee’s) imbecility and incapacity is universally acknowledged by every candid man who is personally acquainted with him.”

Alternatively, a Whig editor, Richard Smith Elliott, candidly summed up: “As a rule we simply assailed Mr Van Buren and his administration, charging all sorts of misdemeanours and corruption.”

Next time viewers become annoyed by comments on Fox News or MSNBC, or both, it is worth considering this history.

The 1840 election set the benchmark for press coverage. Unsurprisingly, it began in New York: “In late 1837, Albany, New York, newspaper publisher Thurlow Weed decided to start a weekly newspaper to promote his political protege, red-haired William Seward, as the Whig candidate in the 1838 race for governor of New York. Weed knew just the man he wanted for the job: the editor of a popular newspaper in New York City. The editor’s name was Horace Greeley, and his publication was The New Yorker.”

Who was paying for this American bounty now at the disposal of the Harrison-Tyler camp? The answer was to be found in a shadowy group of financiers from New York City.

Weed and Greeley were decisive influences in the 1840 contest.

Although their right to vote regrettably wasn’t until decades later, American women were encouraged to participate in the 1840 campaign as active members of log cabin clubs and in the parades and the feasts that normally represented the climax of Whig gatherings. Speeches were not the main attractions. “Free food also was a big part of the allure. Most rallies featured tables full of meats, potatoes, breads, pies and more. At a rally in Wheeling, which was then in Virginia, tables groaned under the load of 300 hams, 1500 pounds of beef, 8000 pounds of bread, 1000 pounds of cheese and 4500 pies. One favourite was a dish called Burgoo, which was made by adding chopped vegetables to a tasty squirrel stew.”

Contrast that with the criticism of former Democratic presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg’s gourmet buffets at his rallies this year.

With largesse of this kind in abundance, questions soon were being asked but never answered of the sources of funding for the Whig campaign.

Who was paying for this American bounty now at the disposal of the Harrison-Tyler camp? The answer was to be found in a shadowy group of financiers from New York City — known as the “merchant princes” — keen to change the administration amid an ongoing recession.

But there was one tactic in which the Whigs excelled: song. Campaign songs were prolific, if not profound. The tradition remains as senator Bernie Sanders appropriated Simon & Garfunkel’s America for his campaigns; Bruce Springsteen regularly leads concerts for the Democratic nominee; and the Rolling Stones have objected to Donald Trump’s use of You Can’t Always Get What You Want without authorisation as he exits rallies. Fortunately, no presidential song has really hit the mark since I Like Ike for Dwight Eisenhower in the 1950s.

So the technologies are very different in 2020, but the campaign methods have not changed dimensionally since William Henry Harrison’s landmark campaign for president in 1840.