A renewed purpose is animating the Australia-Japan relationship.

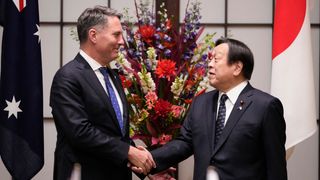

As Richard Marles, Australia's deputy prime minister and defense minister, said in a speech at the Sasakawa Peace Foundation last December, the updated Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation and Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) that the two governments signed last year "give Japan and Australia the bilateral architecture to ensure our defense and security cooperation is commensurate with our strategic alignment."

More recent evidence suggests that Canberra and Tokyo are moving quickly to convert the relationship's baseline potential into tangible gains.

In a joint statement issued on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore last month, aptly entitled "Implementing our shared ambition," Marles and Japanese Defense Minister Yasukazu Hamada indicated that the two countries are beginning to zero in on specific initiatives to build practical cooperation in key areas, including more collaborative defense research and development, more complex joint exercises and expanded access for each nation's military forces to the other's bases.

These initiatives reflect the two countries' mutual interest in strengthening military deterrence in the region in short order, including trilaterally with the U.S.

But moving forward also requires looking back. Implementing a cooperative joint security agenda at scale and speed will require reflecting on how the two countries have gone about this sort of cooperation in the past. In some cases, it may require reexamining lessons that we thought we had learned.

Retracing the scars of the RAA negotiations is key here.

Today, Canberra and Tokyo regard the RAA as both emblematic of the great strides made in advancing the bilateral defense relationship and as a chief enabler of future forms of cooperation.

Yet the way that many observers in the two countries have looked at the future of the relationship has been deeply influenced by the painstaking, near-decadelong negotiations needed to reach the agreement in the first place. For them, the overriding take-away from that period is that advancing bilateral cooperation will always be a tedious and frustrating process.

It is for that reason that some wonder whether the two countries' mutual sense of strategic urgency and ambitious defense agendas will be enough to overcome lethargic bureaucratic settings and lingering political hurdles.

It is for that reason that some wonder whether the two countries' mutual sense of strategic urgency and ambitious defense agendas will be enough to overcome lethargic bureaucratic settings and lingering political hurdles.

This is not an unreasonable view given that the RAA is only being implemented in 2023 while negotiations began in 2014. Nor is it to say that the delays were entirely unwarranted. Deciding whether or not capital punishment would apply to Australian soldiers operating in Japan was a critical issue.

But one has to wonder whether this is the most important lesson that we should take away from the RAA saga if we are serious about trying to implement an ambitious bilateral agenda.

For one, these negotiations were very much a product of their time. And the times, they are changing.

It is worth recalling that this was the first such agreement for Japan with any country other than the U.S., a huge step given Japan's history. Tokyo has since concluded an RAA with the U.K. and flagged others to come with France and the Philippines.

The regional strategic landscape has also evolved markedly since the mid-2010s. The paradigm shifts flagged in Japan's National Security Strategy last December and in Australia's Defence Strategic Review in April, and the two countries' consensus on the need to accelerate defense cooperation with one another like never before, are reflective of the magnitude of the changes in their strategic outlooks.

To be sure, there remains a real political ceiling to deepening cooperation in more sensitive areas like joint strategic and operational planning.

But over-internalizing the lesson from the RAA that steps to implement enhanced defense cooperation will move glacially at best, or at worst not at all, risks overlooking the real opportunities that may exist to move faster within an expanded realm of the possible. Judging the prospects for every such opportunity against something as exceptional as the RAA makes for skewed analysis.

If we are looking for an actionable insight here, we should be focusing on the nature of the end result more than the time it took to get there. In that sense, the more useful lesson to be learned from the RAA saga is not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

If we are looking for an actionable insight here, we should be focusing on the nature of the end result more than the time it took to get there. In that sense, the more useful lesson to be learned from the RAA saga is not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

If clarity on the capital punishment issue was what was needed to make the RAA "perfect," then the RAA is imperfect in that future cases are to be addressed individually depending on the circumstances.

But practically speaking, imperfection is par for the course with such agreements. Even after extensive negotiations, they are rarely fit for purpose in perpetuity.

Changes in strategic and political circumstances and unforeseen technical issues mean that these agreements usually require periodic updates. This is exactly what happened with the 2017 update to the 2010 Japan-Australia Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement, reflecting the impact of Japan's 2015 Legislation for Peace and Security.

Exploring the limits of the possible for Australia-Japan defense cooperation is what the RAA should now facilitate. We may have reached an imperfect agreement, but it is one that for all intents and purposes is good enough to enable the sort of activities required to bolster collective regional deterrence. This is especially important if both countries believe that we do not have a lot of time for our enhanced cooperation to deliver real deterrence effects.

In that sense, perfection in defense cooperation looks like a luxury. But good may be more than good enough.