Introduction

Australia’s long-standing strategic relationship with the United States is transforming in response to the geostrategic change in the Indo-Pacific and a fractious debate in the United States about its role in the world. At the same time, technological change and economic interdependence have reshaped the nature of interstate competition, creating many new vectors of state power. For Australian policymakers and their American partners, creativity and dexterity are in great demand, with the US-Australia alliance growing in scope and deepening in strategic importance.

With a new administration in Washington committed to both the Indo-Pacific and the value of alliances — and 2021 marking the 70th anniversary of the ANZUS Treaty — this volume advances an agenda for the alliance in this critical phase.

This report is a co-production of the United States Studies Centre and the Perth USAsia Centre.

Three key developments are driving swift evolution in Australia’s alliance with the United States — far and away Australia’s most important strategic relationship.

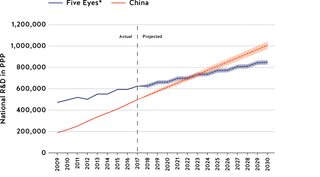

First, strategic competition with an increasingly capable, assertive and authoritarian China is now widely accepted as the single most pressing challenge for the United States and its allies. This change in the US strategic mindset finds no meaningful partisan opposition in Washington and certainly not among relevant officials in the Biden administration.

Second, rapid technological change and deepening economic interdependence have reshaped the nature of interstate competition since the Cold War, the last era of great power rivalry dominating international affairs. Since then, long-standing, conventional vectors of state power have been transformed; examples include the development of stealth, autonomous systems and hypersonics in the domain of conventional military capabilities or the way that technology has transformed intelligence collection and analysis.

Strategic competition with an increasingly capable, assertive and authoritarian China is now widely accepted as the single most pressing challenge for the United States and its allies. This change in the US strategic mindset finds no meaningful partisan opposition in Washington and certainly not among relevant officials in the Biden administration.

International trade and cross-border investment flows have always been vehicles for projecting and acquiring national power and influence but now have a level of strategic significance not seen in living memory. Infrastructure, energy, frontier technologies and higher education are just some of the domains where a rapid shift in mindset is underway, with national security and strategic considerations now much more salient or even paramount. As the COVID-19 pandemic vividly highlights, points of national vulnerability and risk — and conversely, resilience and strength — are being discovered or created at a brisk pace. This re-emergence of economic tools of statecraft, or geoeconomics, is demanding creativity and dexterity from policymakers and moments of reckoning for democratic societies and their leaders.

These developments are of profound significance for Australia and its alliance with the United States. Australia occupies the middle longitudes of the globe’s most important geographic strategic arena, the Indo-Pacific. The Australia-US alliance has rapidly taken a regional focus and emphasis unseen since the Vietnam War. Australia is one of many countries that counts China as its largest trading partner, but, and unusually for an economy of its size, it has also maintained a highly concentrated mix of exports and destination markets. Accordingly, Australia has been, is, and will be, on the frontlines of geoeconomic competition. Unsurprisingly, this too is broadening and deepening the alliance agenda.

Third, understanding the domestic US political and policy environment must factor into any assessment of the alliance agenda, of how to advance Australian national interests through the alliance. Despite deep and bitter partisan acrimony in the United States, there is much for Australians to welcome. The unified stance on China’s coercive manoeuvres across party lines and between countries is a critical alignment to tackle this high stakes and pervasive issue.

Across the US strategic affairs community, Australia’s credentials as an ally of substance are impeccable. Australia is rightly seen as on the “frontlines” with respect to the China challenge and being willing and able to respond credibly. Across nominees and appointees — their speeches and Senate testimony — and announcements about the tasking and resourcing of agencies, it is clear the Biden administration is prioritising the Indo-Pacific and the role and interests of allies and partners. We survey these developments in the chapters of this volume.

But we also identify a number of challenges to Australian national interests in the US domestic political and policy environment.

- The magnitude of the China challenge is accepted across party lines, but this must be backed by spending commitments and focus to translate aspiration and intent into policy, programs and facts-on-the-ground. (See chapter by Ashley Townshend and Brendan Thomas-Noone)

- Protectionism, isolationism and scepticism about multilateral arrangements are also important legacies of the Trump presidency, supercharged by the COVID-19 pandemic’s damage to the US domestic economy, to the United States’ sense of its priorities and its place in the world. (See chapter by Jeffrey Wilson and chapter by Stephen Kirchner)

- US defence budgets were under enormous strain and scrutiny before COVID-19, opening up a gap between operational capabilities and strategic aspirations in the Indo-Pacific. Countries that felt “out in the cold” in Trump’s Washington are vying for presence and influence with the Biden administration (e.g., NATO partners). Internal competition for resources inside the US Government will also risk distraction from the Indo-Pacific. (See chapter by Brendan Thomas-Noone and chapter by Ashley Townshend and Toby Warden)

- The US and Australian governments are chiefly focused on the immediate health challenges of COVID-19, particularly getting vaccines to their citizens, but there remain opportunities for building more resilient public health systems in the Indo-Pacific. (See chapter by Matilda Steward and chapter by Adam Kamradt-Scott)

- Democratic resilience is no longer a concept solely associated with the developing world. From cyber networks to domestic extremism, the internal focus all democratic governments are undergoing is an opportunity for collaboration. (See chapter by Elliott Brennan and chapter by Jennifer S. Hunt)

- The Biden administration has promised to put climate change considerations at the heart of its thinking about foreign policy and national security. This has prompted considerable speculation about the implications for Australia, with its high carbon emissions per capita and reliance on fossil fuel exports. (See chapter by Simon Jackman and Jared Mondschein)

- Geoeconomic threats to American primacy are prompting the Biden administration to explicitly connect domestic recovery to external strength, with reviews of supply chains and strategic, government-led investments to secure US technological supremacy. But any opportunities — and risks — for allies remain unclear. (See chapter by Hayley Channer, chapter by John Lee and chapter by Jeffrey Wilson)

Accordingly, a clear-eyed understanding of Australian national interests — advancing them and advocating for them in these early months of the Biden administration — is vital, central to the mission of the United States Studies Centre, the Perth USAsia Centre and the purpose of the chapters that follow.

Professor Simon Jackman

Chief Executive Officer

March 2021

US domestic politics and policy

Professor Simon Jackman

For Australian national interests, one issue dominates assessments about US domestic politics. What is the appetite of the United States for a return to global leadership? A range of subsidiary questions follow:

- How quickly, and to what extent, will the Biden administration operationalise the strategic aspirations laid out over the 2020 campaign, for a return to multilateralism, for assembling and leading a coalition of allies and partners in countering China’s assertiveness, for increased presence and power in the Indo-Pacific and for the dollars and focus that this will entail?

- What other policy priorities are competing with these issues and how much salience do they enjoy?

- How robust is the bipartisan consensus around the scale and urgency of the China challenge? Will deep partisan acrimony in the United States impede the Biden administration’s ambitious plans for wide-sweeping competition with China?

To rigorously address these questions the United States Studies Centre (USSC) commissioned surveys of the adult, citizen population of the United States, fielded in October 2020 before the November elections and reinterviewing 1,186 respondents in late January 2021, after Biden’s inauguration. These surveys build on USSC surveys in 2019 and earlier years, utilising much of the same question wording so as to permit valid inferences about trends and change in American public opinion on issues of relevance to Australian national interests.

Trump and the pandemic have hardened American views on China

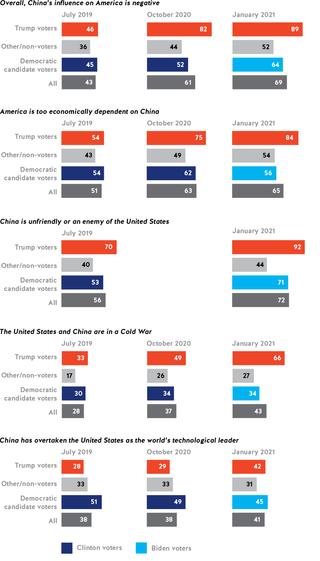

Figure 1. American opinions about China have hardened, especially among Trump voters

Percentage of respondents agreeing, by president vote. 2019, 2020 and 2021 surveys.

In Figure 1 we summarise responses on five propositions about China and its relationship with the United States, comparing results from USSC surveys administered in July 2019, October 2020 and January 2021. American opinions on China were not especially favourable in 2019 and have generally become more negative since. Trump voters, in particular, have moved even more decisively towards negative views of China after the November 2020 election, no doubt driven by Trump’s insistence about the Chinese origins of COVID-19 and its contribution to Trump losing the election.

- As recently as July 2019, less than a majority of Americans held negative views about China’s relationship with the United States, with little partisan variation. By October 2020 and especially by January 2021, 69 per cent of Americans described China’s influence on America as negative, a view shared by 64 per cent of Biden voters in January and by nine out of 10 Trump voters.

- Seventy-two per cent of Americans describe China as unfriendly towards the United States or an enemy of the United States, up from 56 per cent in 2019 (this item was not asked in October 2020). Trump voters moved 22 points on this measure, from 70 per cent to 92 per cent, and Clinton/Biden voters moved 18 points, from a bare majority (53 per cent) in 2019 to 71 per cent in 2021.

- Forty-three per cent of Americans believe the United States is in a Cold War with China, up from 28 per cent from mid-2019, driven not by change among supporters of Democratic candidates, but largely by a doubling of the rate at which Trump voters report this belief (from one-third in 2019 to two-thirds in 2021).

- In 2019 a slim majority (51 per cent) thought the United States was too economically dependent on China, rising to 65 per cent in our January 2021 survey. The change is almost exclusively driven by a hardening of opinion among Trump voters (54 per cent to 84 per cent), with little movement among Clinton/Biden voters.

- A similar story holds for the proposition “China has overtaken the United States as the world’s technological leader.” There is little movement on this item aside from Trump voters, moving from 28 per cent agreement in 2019 to 42 per cent in January 2021.

The elite, Washington consensus on China is largely mirrored in mass opinion, save for the recent and pronounced hardening of views among Trump supporters. Only slim or near-majorities of Biden voters agree that “America is too economically dependent on China” or that “China has overtaken the United States as the world’s technological leader.” But these proportions are sufficiently large — and the issues sufficiently serious — to serve as a reservoir of political capital for the Biden administration’s policy of competition with China.

The risks of isolationism

For decades researchers have measured isolationism in US public opinion with the proposition “America would be better off if we just stayed home and did not concern ourselves with problems in other parts of the world.” Across our three surveys we see an increase in isolationist views in US public opinion, but again with a distinctly partisan character.

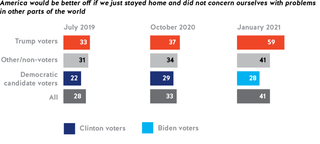

Figure 2. Isolationism has increased dramatically among Trump voters

Percentage of respondents agreeing, by president vote. 2019, 2020 and 2021 surveys.

In mid-2019 we observed that one-third of Trump voters expressed isolationist views, comfortably ahead of the 22 per cent rate among Clinton voters. By October 2020, all groups reported an increase in isolationism: 29 per cent among Biden voters and 37 per cent among Trump voters.

The outcome of the November 2020 election appears to have prompted a massive uptick in isolationism among Trump voters to 59 per cent, no doubt a reaction to Biden’s early actions in reversing some key Trump policies, rejoining the Paris Climate Accord (Paris Agreement) and the World Health Organization (WHO), and promising to restore more conventional relations with American allies and partners. Non-voters and supporters of minor parties and independents also moved towards isolationism between October 2020 and January 2021. Biden voters’ levels of isolationism are unmoved through the election period, further suggestive of the political character of the reaction among Trump voters and non-voters.

One of the defining characteristics of “Make American Great Again,” “America First” and, more broadly, “Trumpism,” is hostility to American engagement in multilateralism, catalysing a resentment to globalisation and internationalism evident since the 1990s, ending the elite-led, bipartisan consensus around the virtues of US global leadership. This hostility clearly endures among Trump voters, and indeed, at levels seldom seen in decades of measuring isolationism. This will be a fault line both between the Biden administration and its Republican opponents, but also, critically, within the Republican Party.

It is widely accepted that Trump-led hostility towards multilateralism, and other isolationist elements of the Trumpian worldview, impeded the effectiveness of the Trump administration’s China policy. Accordingly, a key issue for Australia is whether deeper US engagement and presence in the Indo-Pacific can steer clear of opposition founded in isolationism and instead, more helpfully, be motivated by widely-shared, negative assessments of China’s ambitions and assertiveness.

Competing American foreign policy priorities

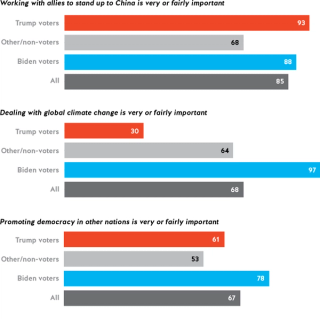

Survey respondents were asked to rate the importance of three foreign policy priorities, “working with allies to stand up to China,” “dealing with global climate change” and “promoting democracy in other nations.”

There is little partisan disagreement about the importance of “working with allies to stand up to China.” Overall, 85 per cent of respondents saw this as a “very” or “fairly” important priority, with 93 per cent of Trump voters and 88 per cent of Biden voters making this assessment.

But a stark partisan difference emerges on climate change. Almost all (97 per cent) of Biden voters rating this as very or fairly important, compared with just 30 per cent of Trump voters. Biden voters are also more likely than Trump voters to endorse democracy promotion as a very or fairly important foreign policy goal, 78 per cent to 61 per cent.

Figure 3. China is rated as important by majorities of Democrats and Republicans, but climate change is even more important for Democrats

Percentage of respondents rating foreign policy priority as “very” or “fairly” important, by 2020 presidential vote. January 2021 survey.

A closer analysis finds that while many Biden voters rate “working with allies to stand up to China” as important, it is almost always subordinate or equal to climate change as a priority. Ninety-three per cent of Biden voters have climate change as their top or equal top foreign policy priority, one-third rate climate change as their single, top foreign policy priority and 28 per cent rate all three priorities as equally important. Only three per cent of Biden voters state that “working with allies to stand up to China” is unambiguously their top foreign policy priority and 13 per cent rank this priority last, behind climate change and democracy promotion.

Table 1. Rank orderings of foreign policy priorities, by 2020 presidential vote

The rank in importance of working with allies to stand up to China, dealing with global climate change and promoting democracy in other nations

|

Importance ranking |

All |

Biden voters |

Trump voters |

Other/non-voters |

|

All equally important issues |

22.8 |

27.7 |

11.2 |

29.5 |

|

Climate most or equal most important issue |

40.9 |

65.0 |

8.0 |

39.6 |

|

China most or equal most important issue |

46.9 |

26.2 |

82.6 |

37.6 |

|

Democracy most or equal most important issue |

18.2 |

13.3 |

23.7 |

19.6 |

|

Climate change least important issue |

20.2 |

2.3 |

50.5 |

12.7 |

|

China least important issue |

8.8 |

12.9 |

0.5 |

12.1 |

|

Democracy least important issue |

20.9 |

29.6 |

11.2 |

17.1 |

For Trump voters, the situation is starkly different, with 57 per cent stating that “working with allies to stand up to China” is unambiguously their top foreign policy priority and just two per cent identifying climate change as their single most important foreign policy priority. Fifty-one per cent of Trump voters rank climate change unambiguously as their least important priority out of the three.

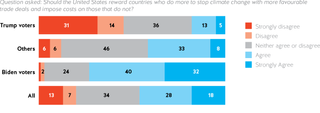

Survey respondents were also asked if the United States ought to “reward countries who do more to stop climate change with more favourable trade deals and impose costs on those that do not” (see Figure 8). Seventy-two per cent of Biden voters agree with this proposition (32 per cent expressing strong agreement) and another 24 per cent are indifferent. Further analysis of the implications of this particular finding appears in a later chapter.

The message for Australian policymakers from this data is clear. The Biden administration’s supporters want the campaign promise of a centrality of climate change considerations to be realised, for climate change considerations to not just be central, but arguably the single most important driver of US foreign policy, and preferably, linked to decisions about trade deals. For Biden’s supporters, “working with allies to stand up to China” is, at most, part of an ensemble of foreign policy challenges.

The Biden administration and Congressional Democrats will find it difficult to ignore this level of political demand from their supporters for climate change to infuse US foreign policy.

Bearing the costs of decoupling from China?

A majority of Americans report that the United States is too economically dependent on China. But are Americans willing to bear the costs that might accompany economic and technological decoupling from China?

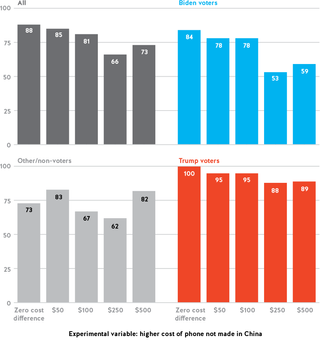

We asked respondents if they would prefer to purchase a cell (mobile) phone made in China or a cell (mobile) phone not made in China, while randomly varying the (hypothetical) extra cost of the phone not made in China “in order to reduce our reliance on Chinese made products” (each respondent was randomly assigned to one of the five price points shown in Figure 4.

The Biden administration and Congressional Democrats will find it difficult to ignore this level of political demand from their supporters for climate change to infuse US foreign policy.

In the baseline condition of no price premium for buying “not made in China,” overwhelming majorities report a preference for buying not made in China: 88 per cent overall, every Trump voter and 84 per cent of Biden voters. Unsurprisingly, increasing costs diminishes preference for the not made in China phone, but even with a premium of $250 or more, at least two-thirds of Americans report a preference for the phone not made in China. Trump voters remain most adamant about preferring the phone not made in China across rising cost differences, with around 90 per cent preferring the phone not made in China despite a $250 or even $500 price premium. Biden voters are the most responsive to the increasing price premiums, but even at the $250 and $500 levels, a majority of Biden voters continue to prefer the phone not made in China.

We concede the “cheap talk” nature of assessing willingness-to-pay in surveys. Even so, we note: (1) preferences for the phone not made in China are high, under any circumstances; (2) a partisan gap is nonetheless apparent but grows larger as the price premium of the phone not made in China increases, suggesting that Biden supporters are most exposed to the costs of technological and economic decoupling from China.

These results do suggest partisan fault lines and limits to US domestic political support for decoupling. This said, while it is a Democratic administration pursuing decoupling, rank and file Democrats are likely to follow the cues of their party’s leaders, tolerating any economic burdens stemming from decoupling, especially if these are offset by other elements of the Biden administration’s “build back better” program. Moreover, Republicans are unlikely to use the economic costs of decoupling from China as a credible line of political attack against Democrats, with Republican members of Congress among the most insistent advocates of decoupling.

Accordingly, we assess high levels of economic and political tolerance for decoupling from China in American public opinion and see little incentive for political leaders in either party to mount opposing arguments.

Figure 4. Americans say they are willing to accept the higher costs of buying “not made in China”

Bars indicate the percentages of respondents saying they would prefer to purchase a cell (mobile) phone not made in China (versus a phone made in China), given different levels of increased cost. January 2021 survey.

Disunity and American democracy

We conclude this introductory survey of the state of US public opinion and politics, and its implications for the alliance agenda, with an assessment of the depth of partisan animus in the United States. Being positively disposed to one’s fellow partisans is to be expected, almost a defining characteristic of identifying as a Democrat or a Republican. But a relatively novel development in American public opinion is “negative partisanship,” reporting negative evaluations of supporters of the party one does not identify with.

We assess two measures of negative partisanship in the United States, using comparable Australian data to put the results in some perspective for an Australian audience.

Through this chapter, and throughout this volume, we identify instances where this partisanship constrains or impedes policymaking — and equally, note those rare instances of bipartisanship — andtheir implications for Australian national interests.

First, we ask respondents if they would be “happy, unhappy, or if it wouldn’t matter” if an immediate family member said they intended to marry someone who is: (a) a Democrat; (b) a Republican; (c) transgendered; (d) a “born again” Christian.

Forty-four per cent of Trump voters would be unhappy if a family member married a Democrat. In contrast, 52 per cent of Biden voters would be unhappy if their family member married a Republican. For Biden voters, this rate of unhappiness at the prospect of a family member marrying a Republican (52 per cent) exceeds the unhappiness rate reported if family members were to marry a transgendered person (19 per cent) or a “born again” Christian (39 per cent).

Corresponding Australian data help put these results in context. Just 17 per cent of Coalition voters say they would be unhappy if an immediate family member intended to marry a Labor supporter; conversely, 28 per cent of Labor supporters and 32 per cent of Greens supporters say they would be unhappy if an immediate family member intended to marry a Coalition supporter. These Australian rates of unhappiness at the prospect of partisan inter-marriage are at most half of the corresponding rates we observe in the US data.

Second, survey respondents are asked to provide “thermometer ratings” of partisan groups, on a zero-to-100-point scale.1 Median ratings of major parties are reported in Table 2, broken down by who the respondent voted for in the most recent national election.

Table 2. Negative partisanship in the United States is far more pronounced than in Australia

Median thermometer ratings of parties, by vote. January 2021 surveys.

|

US data |

Australian data |

||||||

|

2020 vote |

Median rating of Republican Party |

Median rating of Democratic Party |

Party difference |

2019 Vote |

Median rating of Coalition parties |

Median rating of Labor party |

Party difference |

|

Biden |

13 |

80 |

57 |

Labor |

38 |

76 |

38 |

|

Trump |

63 |

5 |

58 |

Coalition |

80 |

46 |

34 |

|

Other/non-voter |

44 |

49 |

5 |

Greens |

22 |

66 |

44 |

|

|

|

|

|

Other/non-voter |

60 |

56 |

4 |

In-party ratings are essentially the same in both countries, around the 80 mark on the zero to 100 cold-to-hot thermometer scale. An exception is the 63 median rating given by Trump voters to the Republican Party, a reaction no doubt to criticism of Trump from Republican leaders after the Capitol Hill insurrection on 6 January 2021, Trump’s subsequent impeachment and Trump’s hostility towards Republican election officials in Georgia inter alia during the post-election period.

The key difference between the United States and Australia are the ratings of out-parties. The median rating of the Democratic Party from Trump voters is just five; the Republican Party gets a median rating of 13 from Biden voters. In Australia, the median out-party ratings are markedly higher: Labor voters give a median rating of 38 to the Coalition parties, while Coalition voters give a median rating of 46 to the Labor Party (barely below the neutral rating of 50). This constitutes more compelling evidence of the depth of partisan animus in the United States and the contribution of negative partisanship to political polarisation in the United States.

The United States transitions from the Trump to Biden presidencies with partisan polarisation at extraordinarily high levels; Australian audiences can only marvel at this critical feature. Through this chapter, and throughout this volume, we identify instances where this partisanship constrains or impedes policymaking — and equally, note those rare instances of bipartisanship — and their implications for Australian national interests.

The Biden agenda, Congress and Australian interests

Joe Biden proposed an expansive legislative agenda throughout the 2020 presidential campaign, spanning racial justice and voting rights, green energy jobs programs, buttressing Obamacare and infrastructure. But sitting above all these issues is control of the pandemic and rebuilding the US economy.

President Biden simply must get his US$1.9 trillion COVID recovery package through Congress (and may well have by the time this volume is published). There is a deep understanding — which Republicans recognise as much as Democrats — that if Biden fails on this first hurdle, his presidency will be permanently damaged. In fact, failure to win congressional approval on the American Recovery Plan will mean that Biden will be unable to win congressional approval of virtually all the other priority measures listed above that he took to the election.

The key to understanding what Biden can accomplish in Congress requires an appreciation of the political dynamics that affected and ultimately overcame, Obama’s presidency. Indeed, the lessons from the 111th Congress — the first two years of President Obama’s first term — are the guideposts for Biden’s strategy and approach in this 117th Congress.2

Like Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, Biden comes to office as a Democratic president with his party in the majority in both houses of Congress. Biden also has an agenda with marked similarities to Obama’s: rebuilding an economy struck down by crisis, addressing an urgent health care reform agenda, securing progress in the epic battle to combat global warming and a host of other compelling social priorities.

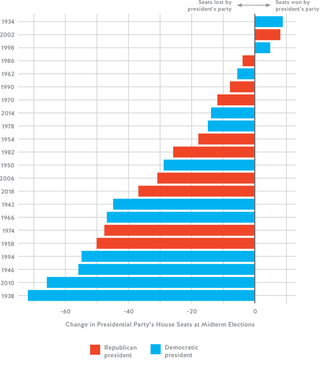

Figure 5. Democrats control Congress, but with razor-thin margins

But unlike Clinton and Obama, Democratic control of Congress is tenuous — just six seats in the House of Representatives and Vice President Harris the tiebreaking vote in the Senate — and at great risk in the 2022 midterms (see Figure 5). Midterm elections typically see the party of the president lose seats. As shown in Figure 6, the midterms of 1994 and 2010 resulted in huge gains for Republicans in House elections, ending unified Democrat control of the federal government and stalling the agendas of both Clinton and Obama. With dogged opposition to the last two Democratic presidents successful in those midterm elections, Congressional Republicans have little incentive to support Biden’s policy proposals. The Capitol Hill insurrection on 6 January 2021 further dampened the already remote prospects of bipartisanship.

Figure 6. Midterm elections typically see the party of the president lose House seats

Biden’s calculus is that if he fails to secure passage of the American Recovery Plan or meet his ambitious vaccination targets (100 million shots in the first 100 days) his presidency is lost too, along with any chance of legislative success on racial justice, climate change and immigration.

As Vice-President, Biden was central to the Obama administration’s protracted and ultimately self-defeating negotiations with Congressional Republicans in 2009 and 2010. Democrats were unsatisfied with the policy compromises that resulted (on recession recovery, on health care, on climate) and lost the House of Representatives: policy pain and no political gain. Biden has no intention of being guilty of repeating that mistake.

This is why Biden is determined to go big and go early, to get the vaccine and economic stimulus in place as soon as possible, and without Republican votes, if needs be.

The House of Representatives

In the 117th Congress that convened in January 2021, the House is comprised of 221 Democrats and 211 Republicans. While margins are immensely tighter than Obama and Speaker Nancy Pelosi faced in 2009, the political dynamics are the same: to be successful, Democrats will have to find the balance on complex legislation within the caucus to ensure that defections do not kill President Biden’s agenda — severely undercutting his presidency. Speaker Pelosi and her leadership team have nearly no cushion for error as the threshold between winning or losing comes down to just a couple of Democrats.

This is all the more important given that the House will be the driver of the Biden legislative program. The key lessons of successful legislative management by the Democrats in the 111th Congress are no less applicable to President Biden and Speaker Pelosi today. In particular, look for:

- Clear and consistent leadership from the President on his agenda and legislation. President Biden’s voice must be forceful, consistent and steady in laying out and explaining what he wants Congress to do, giving assurance to members in swing districts.

- Intensely effective working partnerships between the president, the speaker and her committee chairs. Key to Speaker Pelosi’s success throughout her tenure is her exceptional ability to read the moods and dispositions of the members of the Democratic Caucus and to have those assessments guide chairs of the committees in crafting legislation.

- A vigorous schedule of hearings to underscore the urgency of the legislative agenda. In both Obamacare and the energy and climate legislation in 2009, carefully constructed hearings showed the high degree of consensus of key interests and constituencies behind these major legislative reforms. The health insurance and pharmaceutical industries strongly supported the Affordable Care Act. Energy, chemical and manufacturing companies supported the cap-and-trade bill. These very visible shows of consensus paved the way to advance these landmark proposals.

The Senate

The 50-50 tie in the Senate plus the tie-breaking vote of Kamala Harris gives the Democrats control of the Senate’s agenda, its calendar, committees and critically, which bills come up for votes on the Senate floor.

The biggest initial dividend of control of the Senate for President Biden is that the Democratic majority will generally approve his Cabinet nominees. The withdrawal of Nerra Tanden’s nomination as director of the Office of Management and Budget is the first real hiccough, highlighting the immense power of “red state” Democratic Senators looking to distinguish themselves from their Democratic colleagues (e.g., Manchin from West Virginia).

Even if the House leadership can find agreement among all House Democrats on these contentious issues among all the factions in the party, the lion’s share of the Biden legislative agenda is dead on arrival in the Senate.

Key elements of Biden’s agenda will be subject to the Senate’s supermajority requirement: 60 Senators are necessary to call debate to a close (to end a “filibuster”) and move legislation to a majority vote on final passage. Budget legislation is exempted from the filibuster’s supermajority requirement. Both political parties have at times relied on packaging major policy programs into the reconciliation process like the 2001 Bush Tax Cuts, Obama’s 2010 Affordable Care Act and, most recently, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Biden’s COVID recovery legislation will be considered this way, circumventing compromises with any Republican senators, but underscoring the importance of holding Democratic senators together. This will test Majority Leader Schumer’s political and parliamentary skill, in particular, (a) dealing with the extraordinary negotiating power of “red state” Democratic Senators (who can credibly threaten to vote against the legislation and hence can extract concessions and amendments) and (b) using parliamentary procedures that keep the comprehensive COVID recovery package more or less intact, bringing an up-or-down vote that is much more costly for rebel Democrats to vote against.

Any realistic assessment of the current configuration of Congress must recognise: (a) that there are not 10 Republican votes in the Senate willing to support virtually any element of the Biden agenda; (b) there are limits to what can be legislated via the budget reconciliation process that circumvents the filibuster; (c) there is dwindling appetite for attacking the filibuster itself by enacting changes to Senate rules or for overruling the Senate parliamentarian’s determinations about what can be legislated via reconciliation; and (d) even for majority votes on the Senate floor, all 50 Democrats must vote together, or have defections offset by Republicans crossing the aisle.

Accordingly, even if the House leadership can find agreement among all House Democrats on these contentious issues among all the factions in the party — from the progressives on the left led by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to the moderates who won Trump districts in the suburbs in 2018 and held them in 2020 — the lion’s share of the Biden legislative agenda is dead on arrival in the Senate.

Exceptions that prove the rule

There will, however, be several key exceptions of great relevance for Australia:

Defence spending. In early January 2021, in the closing days of the 116th Congress, both the House and Senate overrode President Trump’s veto of the National Defense Authorization Act, which sets military spending levels and locks in US strategic priorities for the country’s defence posture.3 This was the first time Congress had overridden a Trump veto. This spirit of bipartisan cooperation on defence will carry through the Biden presidency, with most Democrats joining most Republicans to ensure steady commitment to overall US defence policy, spending levels and weapons programs. Defence spending will be a major ongoing target of Democrats on the left in both the House and Senate, but on these issues, the centre will prevail.

Foreign Policy. President Biden has entered office without the United States engaged in major wars overseas. Biden’s much firmer stance on Russia and President Putin, the aim of restoring effective working relationships with America’s allies in Europe and Asia, and Biden’s tougher position on human rights, from Saudi Arabia to Burma to China, will be strongly welcomed. The House and Senate foreign relations committees will be active on legislation that will provide incentives and punishment on human rights issues.

Appropriations and government funding. An enduring trend, even under the Trump presidency, was the ability of the House and Senate to work through the government spending (supply) bills for all the government agencies and their operations. The Appropriations Committees have been able in recent years to reach agreements to keep the government operating. The longest government shutdown in American history, however, occurred under President Trump, who insisted, as a condition of signing legislation to maintain orderly funding of the government, that Congress approve funding for the border wall with Mexico.4 Trump ultimately backed down on his demand and normal operations resumed. This was such a searing political experience that, with a president such as Biden — a creature of Congress — a repeat of that confrontation is highly unlikely.

Congress and Australian interests

There are several major issues directly affecting Australian interests:

China. Leaders in Congress on China policy are highly aware of Australia’s frontline status with respect to China and Australia’s alliance credentials. As in the Trump administration, this bipartisan coalition will serve a valuable role in helping ensure executive branch policy and actions are mindful of Australia’s interests.

Trade. Leaders in Congress on trade will be sympathetic to Australia’s long-standing fidelity to free trade norms and policies and will pay special attention to China’s economic coercion of Australia. There is little evidence of Congressional support of the United States joining the CP-TPP, at least not until the US economy has meaningfully recovered from COVID.

Military posture. As discussed above on the defence spending issues, Congress will welcome continued further deepening and coordination on the military alliance and overall posture in the Asia Pacific, especially with respect to China and its projection of sovereignty and force.

Big Tech. Australia’s strong stance against the market abuses of big tech companies, especially Facebook and Google, has captured the attention of both members of Congress who follow these issues closely and the administration officials and agencies who oversee antitrust and consumer protection issues.5 Conversely, there is little love for Big Tech in Congress nor any chance of Congress being sympathetic to any claims that social media giants have been treated unfairly by Australia.

Climate change — a special case. Climate change and global warming have already proven to be an issue that is directly affecting Australian politics. Biden’s commitment to move aggressively on climate is a pillar of his overall agenda. His stance on climate was crucial to winning the support of Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren for the Democratic nomination. In office, Biden has affirmed reaching stringent carbon-reducing targets by 2050, and has moved aggressively6 through executive orders to reverse Trump policies that rolled back environmental regulations, ended carbon-intensive projects such as the Keystone XL pipeline and permit approvals that would have opened public lands and off-shore tracts to oil and gas drilling.

These measures, especially the support for firm 2050 targets, have provoked political debate here on Australia’s climate policy. Carbon pricing — a critical lever in realising emissions targets — is an obvious threshold issue. It is unclear whether the Biden administration would welcome or propose legislation on carbon-pricing, but a sustained debate in the US Congress on carbon-pricing, even if the legislative passage were to fail, would spill over into Australian domestic politics.

In the interim, there is nothing the Australian Government can say or do that will slow down, delay or stop any action Biden and his climate advisors — led by former Secretary of State John Kerry, who is fully seized of the climate issue — take to address climate change.

In a later chapter we revisit this issue, assessing that while any material divergence in climate policy between the two countries will be an irritant, such differences will not in any way threaten the deep fundamental relationship between the two countries.

An engaged America — led by a President not only supportive of the rules-based, international order but with the political capital to drive the supporting policy and action from Congress — is a stronger and more effective alliance partner of Australia.

We further assess that if Biden were to propose carbon-pricing legislation, Congressional enactment is unlikely. In 2009, the Waxman-Markey “cap-and-trade” program passed the House despite the defection of dozens of Democrats from energy-producing states because of the support of a crucial handful of Republicans. The Waxman-Markey Bill was never brought to a vote in the Senate and died. We doubt that in the current Congress carbon-pricing would even make it out of the House of Representatives, let alone make it to the Senate floor.

This suggests that political spillovers into Australia on climate and emissions will intensify only in so far as a Democratic-controlled Congress actively engages on the issue. US policy proposals will also powerfully shape the terms of debate here on what Australian policy should be.7 Conversely, should Biden climate and emissions policy hit a political wall in Washington — with Congress the key actor — the intensity of Australian debate may not necessarily diminish, but the scope of climate policy options will likely be limited along similar lines.

Australian national interests dovetail with Biden being successful in overseeing America’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. A prosperous, capable and self-confident United States is more likely to take on the burdens of global leadership and projecting power and presence into the Indo-Pacific, of bearing the costs of competition with China.

But there are second-order effects at work too, tying Australian national interests to Biden’s domestic political fortunes. American power and prestige abroad are in no small measure functions of the domestic standing of the incumbent president. Early successes for Biden will earn him political capital for pushing back against the voices of protectionism, isolationism and unilateralism in the Congress. An engaged America — led by a President not only supportive of the rules-based, international order but with the political capital to drive the supporting policy and action from Congress — is a stronger and more effective alliance partner of Australia.

Strengthen the global and regional trade architectures

Context and background

Australia needs to facilitate US re-engagement with the rapidly evolving global and regional trade architectures.

During the Trump administration, the United States withdrew from several important trade institutions, while launching a series of costly — and ultimately ineffective — trade wars. These policies have compromised the integrity of global trade institutions and weakened the benefits of regional trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). While the Biden administration has signalled a change in approach to trade issues, countervailing domestic and international imperatives mean the direction of its trade policy remains unclear. Australia now has an opportunity to shape the trade policy outlook of the Biden administration in a way that favours rule making, multilateralism, and greater collaboration with allies and like-minded partners.

The Biden administration

The Biden administration inherits a ruinous set of trade policies from its predecessor. Trump’s first presidential act was to withdraw from the TPP, greatly weakening an institution that locked in a US-preferred model for trade liberalisation. The Trump administration vetoed new appointments to the World Trade Organization (WTO) Appellate Body, rendering its dispute settlement and rule-enforcement functions ineffective. It aggravated allies and friends by imposing trade balancing agreements under thinly-veiled threats of diplomatic coercion. Most significantly, it prosecuted a self-harming bilateral trade war with China, which has demonstrably failed to either change the US-China trade balance or lever reform to China’s trade practices.

While the Biden administration has signalled an intent to change trade policy, mixed signals mean its new direction remains unclear. On the positive side, it has flagged a more multilateral approach to managing trade tensions with China, recognising that Trump’s bilateral trade war has failed.8 The selection of Katherine Tai — a veteran trade lawyer with deep China expertise — as the next US Trade Representative telegraphs that substantive issues (such as intellectual property) will now dominate the agenda.9 The United States has begun to re-engage with the WTO by supporting the appointment of its next Director-General and may remove the veto on Appellate Body appointments, restoring the global trade dispute settlement mechanism to normal function.10

Table 3. US trade diplomacy under the Trump administration

|

Target |

Year |

Action |

|

Trans-Pacific Partnership partners |

January 2017 |

Withdrawal from Trans-Pacific Partnership, rendering entry-into-force numerically impossible |

|

WTO members |

January 2017 — ongoing |

Systematic veto of Appellate Body nominations to force US-requested governance reforms; Appellate Body became inquorate on 10 December 2019 |

|

Canada and Mexico |

August 2017 — September 2018 |

Renegotiation of North American Free Trade Agreement under threat of termination |

|

Korea |

January — September 2018 |

Renegotiation of Korea-US Free Trade Agreement under threat of termination |

|

World |

March 2018 — ongoing |

Tariffs applied to solar panels, washing machines, steel and aluminium imports on national security grounds; Canada, China, the EU, India, Mexico, Turkey and Russia all impose retaliatory tariffs |

|

China |

July 2018 — ongoing |

Escalating the application of tariffs to demand a bilateral trade agreement, rising to cover $550 billion of imports from China; China repeatedly retaliates, with tariffs imposed on $185 billion of exports from the United States |

|

Turkey |

August 2018 — ongoing |

Removal of Turkey from US Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) scheme; imposition of additional 25 per cent tariff on Turkish steel (enacted August 2018, withdrawn May 2019, reimposed October 2019) |

|

Japan |

April — December 2019 |

Negotiation of a bilateral trade agreement favouring US agricultural exporters under threat of tariff imposition |

|

European Union |

May 2019 — ongoing |

Imposition of retaliatory tariffs on $7.5 billion of EU exports in Airbus dispute; threatened imposition of 25 per cent tariff on automobiles to force a trade-balancing bilateral agreement |

|

India |

June 2019 — ongoing |

Removal of India from the US Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) scheme |

|

Brazil and Argentina |

December 2019 |

Removal of exceptions from steel tariffs in retaliation for alleged currency manipulation |

However, countervailing imperatives mean the Biden administration is also unlikely to fully recommit to trade liberalisation or rule making. Trump’s China tariffs will be politically costly to wind back at home (particularly in the steel sector) and also function as bargaining chips for future negotiations with China. It is unlikely they will be unilaterally reduced in the near term.11 Biden’s “Buy American” pledge12 is not strictly a trade policy but indicates that protectionism will remain a feature of US economic policy. Several selections to the Council of Economic Advisers have a record of trade scepticism, suggesting liberalisation is unlikely to be on the immediate agenda.13 Rejoining the TPP will also be a longer-term proposition, due to opposition within Congress at home and complex negotiations with partners abroad.

Beyond the costs to the US economy itself, trade policy under the Trump administration has been harmful to the global and regional trade architectures. The WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism has been compromised due to Appellate Body appointment vetoes and cannot enforce trade rules in a timely and effective manner.14 The United States has disengaged from regional trade diplomacy, depriving these efforts of the political and economic heft that US leadership offers. Bilateral pressure on China has failed to achieve Trump’s objective of increasing US exports,15 and even then, a focus on trade balancing ignores the real trade policy challenges currently posed by China, such as intellectual property protection and subsidies to state-owned enterprises.

Australian interests

The absence of US trade leadership is a major challenge for Australia. As a highly open economy, Australia depends on a reliable and rules-based trade system. Its medium size means Australia lacks either the economic or political heft to defend its trade interests bilaterally, so multilateral institutions, such as the WTO globally and the TPP regionally, are of critical importance. US disengagement — and at times, non-constructive interventions — threaten the reliability of these institutions. It also deprives Australia of a powerful and like-minded partner to work within new trade negotiations.

US re-engagement with global and regional trade architectures is critical for Australia’s national interests. However, the extent of current US disengagement, and competing domestic and international imperatives, means the direction and pace of trade policy recalibration under the Biden administration cannot be taken for granted. Australia should engage the United States to encourage and shape patterns of re-engagement in 2021 and beyond.

Policy recommendations

- Communicate the importance of a functioning WTO system and collaborate on WTO reform efforts. Australia should clearly reiterate to its alliance partner the value of a rules-based and functional global trading system. It should also work with the United States to support constructive WTO reform efforts, particularly in terms of the smooth functioning of the dispute settlement mechanism.

- Begin preparatory work enabling the United States accession to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Domestic economic priorities in the United States mean its accession to the TPP will be a long-term process. However, preparatory efforts should begin now to address key obstacles. Within the TPP group, Australia should lead discussions on how the (presently untested) accession mechanism will operate. With other major TPP economies — such as Japan, Canada and Singapore — it should start engaging the United States on key reform issues that need to be negotiated. Of key importance are issues to do with the implementation of intellectual property provisions suspended as a result of the United States’ departure from the regional agreement in 2017.

- Support confidence-building through US-Australian leadership in emerging trade platforms. Constructive US engagement in new multilateral trade platforms will help restore global confidence in the United States as a trade policy leader. Australia and the United States could work together in areas of shared priority. A useful starting point is the recently-launched e-commerce negotiations within the WTO, which Australia co-convenes with Japan and Singapore.16 Establishing global e-commerce rules will be essential in protecting the 21st-century industries of these economies and would also signal to the world a more engaged and leadership-oriented US trade outlook.

Enhance health cooperation in Southeast Asia and the Pacific

Matilda Steward

Context and background

Australia and the United States should build on existing commitments to strengthen health security in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. These efforts must focus on addressing the secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which threaten to reverse fragile gains made across broader health and development indicators over recent decades. Despite early containment measures resulting in lower caseloads throughout Southeast Asia and the Pacific compared to other regions, progress in controlling the spread of the virus and the ongoing capacity of national governments to respond to outbreaks remains deeply uneven.17 Diversion of material and human resources to address COVID-19 has placed further strain on already weak health systems, causing significant disruption to essential services and stalling momentum towards universal health coverage.18 An estimated 34.8 million infants throughout Southeast Asia have missed routine vaccinations as a result of the pandemic,19 with health experts warning that efforts to control and eradicate malaria in the Pacific are also at risk.20

The 2020 AUSMIN Global Health Security Statement established a foundation for bilateral cooperation in tackling COVID-19 throughout the region with its pledge to strengthen and accelerate health security capacity building.21 Australia and the Biden administration should recommit to this joint plan of activities with an expanded remit to confront a broader suite of health and development challenges emerging from the pandemic. This approach will be crucial for ensuring collective action strengthens health systems holistically, rather than creating parallel infrastructure that operates solely in response to COVID-19 and generates limited long-term impact.22

The Biden administration

Engagement with multilateral institutions and stronger coordination with allies in meeting global health challenges is a key priority for the new administration. President Biden has stressed the need to “restore US global leadership to fight [the COVID-19] pandemic” and reversed former President Trump’s withdrawal from the World Health Organization on his first day in office.23 The White House roadmap for combating coronavirus includes ambitions for sustained domestic and international funding for global health security that extends beyond emergency funds for health and humanitarian assistance. The administration also intends to enact institutional change, creating an office of Global Health Security and Diplomacy at the State Department and re-establishing the Obama-era Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense within the National Security Council.24 This heightened focus on America’s contribution to health security has been underpinned by personnel appointments with experience navigating pandemics, including Biden’s chief of staff Ron Klain who oversaw the Obama administration’s response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Other picks for key positions — including the Secretary of Homeland Security and Ambassador to the United Nations — also played active roles during the Ebola and Zika outbreaks.25

But translating this momentum into sustained attention and resources for the Indo-Pacific will be a considerable challenge. Securing funding for an expanded international response will require ongoing congressional support in the face of significant challenges facing America’s own COVID-19 response and domestic economy more broadly.26 These efforts will also require a reconceptualisation of American global health financing, which has developed under a model of shared responsibility that encourages recipient countries to increase their own investments in health systems strengthening alongside donor contributions27 Equally, achieving an explicit regional focus will require the introduction of specific directives or initiatives led by senior figures within the US government. For instance, USAID’s Over the Horizon Strategic Review — conducted to provide goals for the agency’s medium- to long-term response to COVID-19 — identified 14 focus countries that combined development need, opportunity for impact, and US national security interests, none of which are in Southeast Asia or the Pacific.28

Australian interests

Enhanced health cooperation with the United States in Southeast Asia and the Pacific would help to ensure a stable and prosperous Indo-Pacific, a key Australian national interest. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Australia had taken significant steps towards raising its profile and commitment to strengthening regional health systems and resilience, namely through the 2017 Indo-Pacific Health Security Initiative and associated Indo-Pacific Centre for Health Security.29 Australia’s new Partnerships for Recovery policy includes health security as a core action area, which, coupled with Australia’s recent commitment of $500 million towards the equitable distribution of vaccines throughout the region, furthers these ongoing humanitarian and reputational efforts.30 Such projects also align with broader regional priorities, including ASEAN’s COVID-19 Comprehensive Recovery Framework which focuses on enhancing health systems and accelerating inclusive digital transformation.31

Table 4. The Australian Government’s COVID-19 development response: Partnerships for Recovery (published in May 2020)

|

Focus + Pacific and Timor-Leste + Southeast Asia + Global response Priority action areas + Health security + Stability + Economic recovery with a cross-cutting focus on protecting the most vulnerable |

|

2019-20: The swift initial response + Our development investments have pivoted to COVID-19 priorities. All continuing investments are addressing development challenges exacerbated by COVID-19. + Immediate distribution of PPE and other critical medical supplies. + $280 million for the Indo-Pacific Response and Recovery Package. + Kept critical transport links open in our region amid global supply chain disruptions. |

|

2020-21: Investing in regional recovery FY2020-21 budget: + A$4 billion in Overseas Development Assistance aligned with Partnerships for Recovery + Including $80m commitment to Gavi-COVAX Advance Market Commitment Additional targeted measures: + $304.7m COVID-19 Response Package Pacific and Timor-Leste + $23.2m Vaccine Access and Health Security Pacific, Timor-Leste and Southeast Asia + Response detailed in 27 tailored COVID-19 Development Response Plans |

Pooling resources in pursuit of joint objectives will also enable Australia to step up its engagement throughout the region. Despite recent statements by Prime Minister Morrison that “ASEAN’s centrality is at the core of Australia’s vision for the Indo-Pacific,”32 Canberra’s pivoted aid program focuses primarily on the Pacific, Timor-Leste and Indonesia due to the presence of pre-existing partnerships.33 As the largest source of bilateral COVID-19 aid to Southeast Asia — with major contributions to the Philippines, Cambodia and Myanmar — further collaboration with the United States can help Australia bridge this gap.34

Policy recommendations

Australia and the United States should:

- Partner to protect and restore essential health services in priority countries. These efforts could focus on the delivery of routine immunisations that have been disrupted during the pandemic, or on a specific infectious disease at risk of re-emergence.

- Commit to joint investments in digital health technologies. These would offer opportunities to support better care and disease surveillance and can act as an important tool for public communication during health emergencies. Financing should address the digital divide and ensure equitable access for rural communities and women. Such investments would align with the goals of the WHO 2020-2025 Global Strategy on Digital Health and present an avenue to operationalise the MOU between the United States Agency for International Development and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade from July 2020 supporting high-quality and sustainable development outcomes in partner countries through digital connectivity.35

- Deepen regional and bilateral engagement in the Pacific. Australia should express its support for bipartisan legislation currently before Congress that provides an expanded framework for US foreign policy in the Pacific islands. The Boosting Long-Term US Engagement (BLUE) Pacific Act proposes increased diplomatic and development presence, supports public health programs, and proposes funding of more than triple current levels of assistance. Importantly, the framework would integrate the US approach with other partners including Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Taiwan.36

Re-engage the United States in global health security

Associate Professor Adam Kamradt-Scott

Context and background

The recent change in presidential leadership provides a key opportunity for Australia to engage the United States in strengthening global and regional health security. Within weeks of President Biden taking office, several Trump administration policies relating to global health were retracted or overturned. This notable change in direction has been described as the United States returning to its former global leadership role, but the reputational damage will take longer to repair. World leaders and global health experts have pointed to the vacillation between Republican and Democratic administrations on multiple policy issues like the global gag rule,37 and more recently the former president’s attack on the World Health Organization,38 which have contributed to a perception the United States is unreliable. This presents an opportunity for Australia to work closely with the United States to repair the country’s standing in the global health community while simultaneously strengthening regional and global health security.

The Biden administration

On assuming office, President Biden moved to revoke several decisions of the former administration pertaining to global health. As pledged during the election campaign, on his first day in office, President Biden retracted the Trump administration’s effort to withdraw the United States from the World Health Organization.39 The day after the inauguration, the administration released its National Strategy for COVID-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness in which restoring US leadership and advancing health security to be better prepared for future health threats was identified as one of seven priority goals.40 Coinciding with the strategy document’s release, Dr Anthony Fauci confirmed to the World Health Organization’s Executive Board that the United States would join the COVAX initiative that seeks to provide two billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines to low and middle-income countries, increase technical cooperation, and re-engage in multilateral efforts to defeat COVID-19 and ensure enhanced preparedness.41 To assist in coordinating these efforts, the Biden administration has re-instituted the National Security Council Directorate on Global Health Security and Biodefense and pledged to reinvigorate the Global Health Security Agenda,42 both of which were initiatives of the former Obama administration but which had languished under President Trump.43 Further measures, such as creating a National Center for Epidemic Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics, advocating for the creation of a new United Nations facilitator for biological threats, and working with multilateral partners including the G7, G20, ASEAN, and African Union to strengthen preparedness are also outlined in the National Strategy.44

Table 5. Status of the Biden administration’s proposed actions on global health and pandemic response (as of 4 February 2021)

|

Action |

Requires Administrative or Congressional Action? |

Status |

|

Restore the National Security Council’s Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense |

Administrative |

✔ |

|

Rescind the Mexico City Policy |

Administrative |

✔ |

|

Restore funding to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) |

Administrative |

✔ |

|

Release a National COVID-19 Response Strategy, including a strategy for international engagement |

Administrative |

✔ |

|

Restore funding to WHO and reverse Trump administration decision to withdraw from WHO membership |

Administrative |

✔ |

|

Support the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator and join COVAX |

Administrative/Congressional* |

✔ |

|

Create position of Coordinator of the COVID-19 Response and Counselor, reporting to the President |

Administrative |

✔ |

|

Develop a diplomatic outreach plan led by the State Department to enhance the US response to COVID-19, including through the provision of support to the most vulnerable communities |

Administrative** |

✔ |

|

Provide US$11 billion to support “international health and humanitarian response,” including efforts to distribute countermeasures for COVID-19, build capacity required to fight COVID-19 and emerging biological threats |

Congressional |

Proposed |

|

Ensure adequate, sustained US funding for global health security |

Congressional |

Proposed |

|

Expand US diplomacy on global health and pandemic response, including elevating US support for the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) |

Administrative |

Proposed |

|

Call for the creation of permanent international catalytic financing mechanism for global health security and work with international financial institutions, including multilateral development banks, to promote support for combating COVID-19 and strengthening global health security |

Administrative |

Proposed |

|

Call for the creation of a permanent facilitator within the Office of the United Nations Secretary-General for response to high consequence biological events |

Administrative |

Proposed |

Australian interests

Australia’s interests are best served by seeing the United States re-engage with the global health community, but it is unlikely the United States will return to the leadership role it once assumed. There are two key reasons for this. First, for at least the initial 12-24 months of the Biden administration, the government will be appropriately focused on containing the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (commonly known as the coronavirus) throughout the United States. This is likely to focus resources and attention on the United States’ domestic situation in the near term. Second, several other countries sought to fill the leadership vacuum created in global health governance by the Trump administration's America First’ policies, and now appear unwilling to cede that influence, viewing the United States as an “unreliable ally.”45

Australia can play an important diplomatic role in supporting the United States — including the endorsement of its reliability as a trusted partner — where shared interests exist. It can also actively seek out a number of new opportunities to enhance US-Australia cooperation. Global health security is one such area. The Australian Government’s regional health security initiative that witnessed the creation of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT)’s Indo-Pacific Centre for Health Security,46 the recently announced A$500 million regional vaccine initiative,47 and efforts between the US military and Australian Defence Force to strengthen civil-military health cooperation across the Indo-Pacific have provided a solid basis for further US-Australia cooperation.48 Strengthening and building on these existing initiatives, aligning development assistance to prioritise strengthening health systems and workforces, re-invigorating some of the health-related multilateral initiatives, and working constructively together to reform the World Health Organization offer a number of opportunities to not only counter moves by other countries to increase their influence throughout the region but also demonstrate a re-engaged and responsive United States.

Policy recommendations

- Initiate ministerial discussions for a joint regional health security initiative involving the United States, Australia, Japan and India. Renewed interest in ‘The Quad’ multilateral arrangement provides a key opportunity to now strengthen regional health security, which reflects long-standing shared interests by all four governments. Intra-regional vaccine production and distribution could provide an immediate area for collaboration while intergovernmental talks commence to identify new synergies and areas for cooperation in strengthening regional disease surveillance and response capacities.49

- Further strengthen civil-military cooperation in health security in the Indo-Pacific region. As documented in the 2019 AUSMIN statement on global health security,50 the US military Indo-Pacific Command and the Australian Defence Force have made good initial progress in strengthening civilian and military cooperation for health security. These efforts are only at a nascent stage though and can be further expanded via providing technical assistance and training to other militaries in the region engaged in health assistance. These measures would create new opportunities for military-military cooperation while also serving to strengthen civil-military norms and enhance regional stability and security.

- Strengthen and re-invigorate the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA). The GHSA initiative was launched in 2014 under the Obama administration and offers a viable intergovernmental platform for supporting countries in the Indo-Pacific region to strengthen their capacities in disease detection, surveillance and response.51 The GHSA, which languished under the former Trump administration, could be relaunched and repurposed to collaborate with other multilateral institutions such as the Asian Development Bank and World Bank to provide targeted development assistance for regional health system strengthening and workforce capacity building. The GHSA could also be used constructively to develop consensus on key issues, such as reform of the World Health Organization and proposals to strengthen multilateral cooperation in global health security.

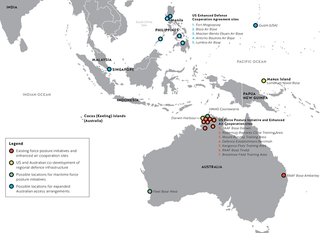

Activate the Australia-US-Japan trilateral infrastructure partnership

Context and background

Australia, the United States and Japan should activate trilateral mechanisms to support the private sector to take up infrastructure funding initiatives in the Indo-Pacific. Amidst the many upheavals of 2020, the value of infrastructure partnerships in the Indo-Pacific to Australian foreign and security objectives has fallen by the wayside. This issue matters because one of the most permanent ways in which China’s claims to regional leadership is being asserted is via the provision of the Indo-Pacific’s underpinning infrastructure. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is providing essential transport and information connectivity to the region, however, BRI projects are not always transparent, nor do they meet global quality standards.

With the small and medium economies of the Indo-Pacific region looking to build critical infrastructure to meet the demands of their populations and growth, there is a small and fast-closing window of opportunity for Australia, the United States and Japan to capitalise on this moment.

Australia, the United States and Japan all agree that to provide regional partners with fair, open and ethical financing alternatives — and to compete effectively with the BRI, they must leverage the resources of the private sector. Leveraging private sector capital and expertise in our development agencies’ infrastructure programming is critical to increasing our impact and strategic success. With the small and medium economies of the region looking to build critical infrastructure to meet the demands of their populations and growth, there is a small and fast-closing window of opportunity for Australia, the United States and Japan to capitalise on this moment.

Launched partly in response to China’s BRI, in November 2018 Australia, the United States and Japan announced the Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific.52 The Trilateral Partnership aims to provide regional governments with an alternative, transparent source of infrastructure funding and emphasises working with the private sector to improve outcomes relative to purely state-financed programs like the BRI. In November 2019, the Trilateral Partnership announced the Blue Dot Network (BDN) — an initiative to reduce the risk for private investors by providing certification for government, private sector, and civil society infrastructure projects that met international quality standards.53 While primarily a certification body, it can also provide access to US$60 billion in capital in loans or equity through the US International Development Finance Corporation (US-IDFC). However, specific mechanisms remain to be determined.

Figure 7. Chinese investment and contracts in the Indo-Pacific, 2014-19 (US$ billions)

Despite efforts by the Trilateral Partnership, no public-private infrastructure projects have been cemented. The first and only project under this trilateral framework — an undersea fibre optic cable connecting Palau with the Indo-Pacific — is being done in partnership with the Palau Government rather than industry.54 The only other project on the horizon is an undersea cable connecting Santiago with Sydney55 but again, progress is slow — discussions between Canberra, Washington and Tokyo for a project focused predominantly on Australia and Chile will likely be continuing. Furthermore, other than BDN’s inaugural trilateral Steering Committee in January 2020 — which discussed a possible vision statement, membership criteria, and responsibilities56 — the BDN has yet to issue certification standards businesses can benchmark against more than a year later.

The Biden administration

As evidenced by the last two years, Australia’s, the United States’ and Japan’s development agencies’ infrastructure programming is not adequately structured to facilitate private sector take-up. In the case of the United States, not even a major restructure of its development agencies in 2018, whereby the Overseas Private Investment Corporation was transformed into the US-IDFC,57 has addressed this issue.

Although the US-IDFC possesses new development finance tools specifically designed to support private-sector-led projects such as small grants, loan guarantees, and equity investments, several factors including lacking communication and an inaccessible online interface are keeping business away.58 Following a meeting of the Trilateral Infrastructure Partnership with Vietnam in October 2020,59 the US-IDFC has yet to make any further public announcements regarding the progress or future direction of this initiative60

Australian interests

Supporting strategic infrastructure projects remains one of the most tangible ways to promote growth, demonstrate regional leadership, and further Australia’s national interests. Australia can maximise its impact in this space by working with like-minded partners and leveraging private-sector investment. However, clearly, there have been challenges to working trilaterally and getting the private sector on board.

Part of the difficultly is that Australia, the United States and Japan have separate, not always equal, infrastructure priorities, and the wide range of regional infrastructure needs can scatter focus, preventing the establishment of a project pipeline. In addition, to lift the BDN out of obscurity, some basic benchmarks must be set and the commercial benefits to certification proactively pushed out to business. Further, a review of the US-IDFC to understand the positive and negative effects of the restructure on attracting private investment could assist the United States to make adjustments as necessary, as well as help Australia and Japan decide if and how they should implement similar changes within their own development agencies.

Policy recommendations

Australia, the United States and Japan collectively should:

- Discuss the potential for a trilateral infrastructure hub established in Southeast Asia, initially dedicated to one aspect of infrastructure provision to the region. A central hub that focused on one major project, for instance, internet connectivity, would help narrow focus. The three countries could then reach out to industry partners in the field and cultivate and leverage business expertise to deliver similar projects to multiple countries over several years. A hub and single-area focus would help catalyse the Trilateral Partnership reputation in the region as a credible alternative to the BRI.