Executive summary

- Inclusive regional institutions, including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the East Asia Summit (EAS), ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus) and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), remain key components of a successful United States Indo-Pacific strategy.

- Comprehensive engagement with these institutions benefits the United States in at least five ways, in that it:

- enables efficient access to a wide network of regional officials through sideline discussions;

- presents the United States as a positive regional player, committed to all countries, not just those with whom strategic interests most closely align;

- prevents China from dominating regional institutions and diplomacy;

- amplifies Washington’s voice on key regional issues and helps it shape the regional narrative in its favour;

- helps the administration focus its time and attention on the Indo-Pacific. - The Biden administration has laid a solid foundation for its engagement with these institutions by attending all key meetings in 2021. In doing so, it redressed the counterproductive neglect of the Trump administration, with President Trump never attending the annual East Asia Summit.

- In contrast to the Obama administration, which made Asian multilateralism a key pillar of its ‘Asia pivot,’ the Biden administration appears to have relatively modest expectations for cooperation with ASEAN, the EAS and APEC, preferring the impact of narrower groupings of like-minded countries such as the Quad.

- This shift reflects the trend of growing strategic competition between Washington and Beijing, which has eroded hopes that inclusive regional institutions would be able to promote dialogue and reduce the risk of conflict.

- Moreover, the United States’ retrenchment from regional trade arrangements has also limited Washington’s interest in pursuing economic cooperation through existing groupings.

- Failure to fully harness the potential of regional multilateral institutions would undermine the success of the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific approach and would contribute to a perception that the United States is not fully invested in its relationships with Southeast Asian countries.

- Australia continues to rely on regional multilateral institutions for access and influence. US disengagement would fatally wound these groupings and strengthen the weight of narrower groupings where China has greater influence, which would harm Australia’s interests.

Recommendations

- The United States should continue to use the upcoming calendar of ASEAN, APEC and G20 meetings to drive focus, resources and official travel to Asia.

- President Biden should offer to host ASEAN leaders for a special summit in the United States in 2022 to commemorate the 45th anniversary of its diplomatic relationship with ASEAN.

- The United States should seek to upgrade its partnership with ASEAN to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership at the next US-ASEAN summit, to be held in Cambodia in 2022.

- The United States should develop a new flagship initiative on a mutually relevant topic, such as energy, to be delivered in partnership with ASEAN, to be announced at the next US-ASEAN Summit.

- The United States should continue to invest time and resources in the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus, which continues to offer important opportunities for security cooperation.

- In developing its Indo-Pacific economic framework, the United States should avoid undermining existing relevant regional groupings, including the EAS, APEC and Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

- The United States should prioritise its relationship with Indonesia, given its current and future influence within ASEAN.

Introduction

As US-China strategic rivalry in the Indo-Pacific intensifies, regional multilateral forums will be critical in the competition for influence and indispensable for a successful US regional strategy. Importantly, in its first year, the Biden administration has attended key meetings — redressing the worst of the Trump administration’s neglect. Yet it still has considerable ground to make up — Beijing has invested assiduously in regional institutions to its advantage in recent years. It devotes considerable energy towards regularly establishing new dialogues and cooperative mechanisms. In 2021, it upgraded ties with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” and hosted a summit with Xi Jinping, rather than Premier Li Keqiang, for the first time.

The United States needs to meet this challenge by articulating a new strategy for regional institutions — including its relationship with ASEAN and its participation in the East Asia Summit (EAS), ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus) and Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) — to maximise its regional influence. This should be pursued in parallel with cooperation in narrower groupings such as the Quad. A failure to do so would cede strategic advantage to China and contribute to the further erosion of inclusive multilateral institutions in which all countries have a voice.

This report makes recommendations for how the Biden administration can best harness the potential of key Asian regional multilateral groupings to advance a successful Indo-Pacific strategy.

These questions matter to Australia. For the past 30 years, Australia has supported inclusive regional security and economic architecture, in part for its role in entrenching the United States in the region.1 This has succeeded, with Australia playing a role in the establishment of APEC and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and supporting the expansion of the EAS to include the United States, all of which helped focus Washington’s attention on Asia. Within these institutions, Australia has historically had influence over US Asia policy.2 Inclusive regional institutions augment Australian access and influence. Canberra has a strong interest in continued US presence in these forums to bolster their success and to avoid elevating the prominence of exclusive groups in which Beijing has greater influence.

This report examines the evolution of US interests in key Asian regional multilateral groupings throughout the Clinton, George W Bush, Obama and Trump administrations. It argues that two key interests, namely commitment to advancing regional economic integration, and to deepening political-security cooperation through regional institutions, have evolved substantially since the 1990s. Three enduring pragmatic rationales should continue to drive US participation: the opportunity to advance the administration’s own regional narrative and preferred norms; the need to prevent China from exclusively dominating regional groups; and the chance to focus administration resources and priorities towards the Indo-Pacific. The report makes recommendations for how the Biden administration can best harness the potential of these groupings to advance a successful Indo-Pacific strategy.

1. Regional institutions in Indo-Pacific strategy: potential and pitfalls

Inclusive regional institutions will always play a complementary, rather than foundational, role in US Indo-Pacific strategy. The institutions themselves — defined here to focus on the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)-centred groups such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), East Asia Summit (EAS) and ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus) — are relatively slow-moving and weakly institutionalised, limiting the role they would play in any country’s regional strategy. As a superpower, the United States has natural preferences for dealing bilaterally, and would never allow such groups to mediate its core security interests.3

Moreover, the current regional environment is becoming less conducive to genuine multilateral cooperation.4 In the 1990s, when Asian regional institution-building had its heyday, countries like Australia and the United States hoped over time regional organisations could play a valuable if modest role as forums for dialogue, consensus-building and functional cooperation. Around 2010, when the EAS was expanded to include the United States and Russia, and the ADMM-Plus formed, participants hoped such meetings could help lower the risks of conflict and promote strategic dialogue among the region’s major powers.

The region today is far more contested than in the 1990s, with the United States and China increasingly seeing each other as systemic rivals in a contest to shape the regional order. As the scope for bilateral cooperation between Beijing and Washington narrows, hopes have diminished for regional institutions to play a meaningful role as a forum for constructive political-security dialogue. These more confrontational relations between China and the United States have put pressure on the ASEAN-centred institutions’ ability to address sensitive issues like the South China Sea and Korean Peninsula.

Regional economic dynamics have also shifted, undermining the role of cooperative economic institutions. This has primarily been driven by Washington’s own shift away from trade liberalising policies and towards a more protectionist economic agenda. Such shifts have undermined APEC, which was already suffering from a poorly defined mission and weak ambition from its members to deliver on its founding mission of regional economic integration. The Biden administration has proposed an ‘Indo-Pacific economic framework’ which will likely fall short of a comprehensive regional trade agreement such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a successor agreement to the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiated by the Obama administration.

Even Southeast Asian countries themselves appear at times to attach less importance to ASEAN than they once did. Some officials and analysts from Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s most consequential power, argue that ASEAN should no longer remain the cornerstone of Jakarta’s foreign policy.5 ASEAN’s own internal divisions, which have been exacerbated by China’s ability to influence its smaller members, have arguably undermined its credibility with external partners.6 And yet there is no serious momentum for reform to improve ASEAN’s internal coherence or ability to respond to external challenges.

Despite these limitations and challenges, multilateral forums remain essential to US Indo-Pacific strategy. Past experience, and the examples cited in this report, demonstrate that when the United States brings appropriately skilled diplomacy and a consistent focus, these forums offer many opportunities. These include the opportunity to connect with many counterparts efficiently in one place and at one time, as well as to showcase its credentials as a responsible, active and valuable regional player, and to use regional processes cleverly to advance its own strategic or tactical objectives.

These opportunities are particularly important for the Biden administration, which faced high expectations it would rectify the Trump administration’s confrontational and unilateralist approach to regional relations.7 Yet the Biden administration was relatively slow to engage with Southeast Asia: it took nearly six months for the administration to send a cabinet-level official to the region, with more diplomatic energy focused on advancing its major alliances and partnerships, such as with the Quad countries, than winning influence in smaller ‘swing states’ in the regional competition for influence with China.8 Because regional groups offer ready access to these countries, they are particularly important for redressing this imbalance in US regional strategy.

Beijing’s choice in 2021 to offer ASEAN a summit with President Xi Jinping, rather than Premier Li Keqiang, who normally represents Beijing in such meetings, indicates that China sees the advantage of investing time and attention in these forums.

There are also significant risks associated with neglecting these forums. Indeed, criticism for missing them is generally louder than praise for turning up. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice missed the ASEAN Regional Forum in 2005 and 2007, generating negative media commentary and headlines about United States’ neglect, ceding an advantage to China.9 After President Obama began the practice of regularly attending the EAS, the president’s presence at this meeting is now seen by regional observers as a litmus test of the US commitment to, and interest in, Southeast Asia. However, even President Obama missed one EAS in 2013 due to a government shutdown at home, resulting in headlines questioning his commitment to Asia.10

More generally, any US absence at key regional meetings would give an advantage to Beijing. China overcame its early distrust of these institutions and now invests assiduously in its partnership with ASEAN, as well as a range of additional Sino-centric institutions and arrangements including the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation forum (LMC) with mainland Southeast Asian countries,11 the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Belt and Road Initiative. Beijing’s choice in 2021 to offer ASEAN a summit with President Xi Jinping, rather than Premier Li Keqiang, who normally represents Beijing in such meetings,12 indicates that China sees the advantage of investing time and attention in these forums.

The challenge for the United States, then, is to articulate a strategy for these institutions which simultaneously accepts their practical limitations and embraces the opportunity they present to strengthen its influence in Asia. This should not be mistaken for a recommendation the United States take an overtly competitive tone in its regional engagement. This divisive approach, pursued by former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who was overtly hostile to the Chinese Communist Party, would only accentuate concerns that the United States is asking regional countries to choose between it and China.13 Instead, just as it is doing in the Quad, Washington should use ASEAN-led groups and APEC to position itself as a positive, constructive, and essential regional player.

2. Economic interests: from trade liberalisation to disengagement

The earliest motivation for US participation in regional institutions in the late 1980s was to support economic cooperation with and among countries in Asia. This cooperation has taken many forms including regional trade negotiations, the “open liberalism” of APEC, and functional cooperation in various groupings. It reflected two US beliefs: first, that Asia is a dynamic region of the world, offering the United States important economic opportunities, and that gains can be made by working at the regional level, below the level of the World Trade Organization and broader multilateral groupings, but above individual bilateral arrangements. Second, it has also reflected US interest in avoiding exclusionary East Asian groupings, which have regularly presented themselves as alternatives to ‘trans-Pacific’ forums that include the United States, Australia and others.

Economic factors preceded security considerations for US participation in regional forums in the 1990s. In 1989, the United States joined the first ministerial meeting of APEC in Canberra. In proposing the grouping, Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke set out three objectives that served Australia’s economic interests: contributing to global multilateral trade liberalisation efforts, dismantling barriers to trade in the region, and coordinating economic policy, for example on science and technology research.14 Seeing the strategic rationale for deeper integration between the United States and Asia, Secretary of State James Baker, serving under President George H W Bush, endorsed the proposal as an “idea whose time has come.”15

In 1993, the new Clinton administration elevated APEC from the ministerial to leader level. It saw APEC as a vehicle that could advance its global and bilateral trade priorities. From a global perspective, the United States wanted to put pressure on protectionist European policies in the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations. Referring to the European Union, incoming US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian Affairs Winston Lord said APEC could help “[dampen] the appeal of exclusionary regional blocs.”16 President Clinton was more explicit following his 1993 hosting of APEC leaders, delivering a message to Europe: “We want them to join us in a new world trading system.”17 The Clinton administration continued using APEC as a forum to generate momentum in world trade negotiations, citing the APEC leaders’ 1996 call to conclude an information technology agreement, and a 2000 call to launch a new round of trade negotiations as key achievements.18

The United States hoped APEC could help it manage economic relations with Japan and China, which in 1993 were perceived by the United States as unbalanced. Australian Trade Minister Peter Cook agreed that an important ancillary purpose of APEC could be for the United States and Japan to help resolve their disagreements on trade in a way that would benefit the region as a whole.19 APEC did have modest successes on bilateral trade matters early on. According to economist and intellectual architect of APEC Peter Drysdale, “The APEC Summit in Manila provided a congenial setting for presidential talks aiming to set United States-China relations on a more productive course.” Drysdale also noted that APEC usefully served as a vehicle for China’s liberalisation agenda and helped support its entry into the WTO.20

The United States also saw APEC playing an indirect security role, by boosting prosperity and entrenching its own role in Asia-Pacific institutional arrangements. Writing in 1991, James Baker set out the case for APEC as a prospective forum to forge a greater sense of an Asia-Pacific community and connect the spokes of the US alliance system.21 President Clinton shared this view, describing economic discussions as one of several “overlapping plates of armor” which could enhance regional security by lowering barriers to trade, generating jobs and easing regional tensions. The goal, Clinton said, was to integrate and engage, not isolate, the region’s major powers, including China.22 More generally, officials in his administration hoped that a US commitment to seeking economic opportunities in Asia would be seen as evidence of its enduring commitment to the region.23

Subsequent US administrations continued to participate in APEC, but without the same early enthusiasm for the forum’s original trade liberalising mandate. Even by 1997, the organisation was described as losing momentum and in need of reform.24 Changing dynamics in global trade negotiations — with multilateral talks stalling, and bilateral deals exploding — squeezed APEC’s room to fill its original economic mandate.25 And the United States grew impatient with the APEC model of voluntary commitments, or “open regionalism,” instead of the more conventional “reciprocity” approach to negotiations, which would have better suited US trade interests. While APEC countries continue technical cooperation on a vast range of topics — from competition policy to intellectual property and energy — most of its progress has been on niche topics, such as trade in environmental goods and information technology products.26 Vice President Kamala Harris’ choice of words when she announced the United States offer to host APEC in 2023 reflects vague ambitions for the forum. APEC, she said, helped “build an interconnected region that advances our collective economic prosperity.”27

By offering countries better access to its huge market, the United States would have been able to play a pivotal role in setting standards on issues such as labour and environmental regulations, as well as positioning itself on future issues such as digital trade.

Reflecting the lack of progress within the broader APEC grouping towards a “Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific,” a smaller subset of countries launched negotiations for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2008. A TPP with the United States as its central anchor would have increased US regional influence. By offering countries better access to its huge market, the United States would have been able to play a pivotal role in setting standards on issues such as labour and environmental regulations, as well as positioning itself on future issues such as digital trade. As with APEC under the Clinton administration, President Obama advanced a national security, as well as an economic case, for the agreement, arguing that by reducing poverty and increasing economic integration, the United States would be safer.28

This argument, however, has not carried the day in Washington. Obama was not able to secure ratification of the TPP in Congress and in 2017, the Trump administration withdrew from the deal. The Biden administration appears uninterested in joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a grouping of the remaining 11 countries, allowing trade promotion authority, a provision enabling fast-track legislative review of trade deals like the CPTPP, to lapse in June 2021.29

During his attendance at the October 2021 EAS, President Biden acknowledged the need for the United States to strengthen the economic aspects of its Indo-Pacific engagement. He announced his administration would work with partners to develop an “Indo-Pacific economic framework” focusing on shared objectives in a range of areas, including trade facilitation, the digital economy and clean energy supply chains.30 Falling short of a multilateral trade agreement, this new “Indo-Pacific economic framework” is likely intended to compensate for its unwillingness to join the CPTPP.31

Recognising the need to develop an economic strategy for the Indo-Pacific is particularly important in light of the current weaknesses of APEC and the US absence from the CPTPP. Washington has never regarded ASEAN-centred forums and processes as suitable vehicles for its own regional economic strategy.32 The United States never joined Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations, judging that the outcomes would not meet US standards for trade agreements. Since the launch of negotiations in 2012, RCEP has been the main platform for external partners to engage with ASEAN on economic matters. This remains a point of difference between the United States and its allies, with countries such as Australia and Japan generally supporting an economic focus in the EAS and ASEAN forums.33

It is unclear how the proposed Indo-Pacific economic framework will interact with existing regional economic institutions. It is unlikely that the United States would seek to develop this initiative in forums that include China, such as APEC or the EAS Economic Ministers’ meeting. However, it will be important the administration considers existing arrangements to avoid further undermining them or developing parallel competitive structures (see Recommendations). This objective would be particularly important from an Australian perspective, given that Canberra continues to support existing economic frameworks through RCEP, CPTPP and APEC processes.

3. Security interests: from mediating the great powers to defence networking

The second main driver of US participation in regional institutions has been the aspiration to shape a more favourable regional security environment. At its most ambitious, this has encompassed the idea of helping mediate great power relations; at its least ambitious, the idea that by establishing networks of officials who are familiar with each other, crises and conflict can be avoided or more readily de-escalated. The United States has never looked to regional institutions as the primary way of securing these objectives before, framing its participation in such forums as complementing its bilateral security alliances and forward military presence.34 Yet the emergence of a more intensely competitive US-China dynamic has weakened even modest hopes for positive regional security cooperation.

The Clinton administration was the first to accept the potential of regional forums to assist in regional security matters: the George H W Bush administration argued regional security concerns were too complex and diverse to benefit from collective security institutions.35 The first such institution was the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), a ministerial and officials’ level gathering of 27 countries formed by ASEAN in 1994. Speaking in 1993, Bill Clinton contrasted his administration’s support with Baker’s opposition, arguing that regional security dialogues could supplement US alliances and forward military position, rather than detracting from them.36

The Clinton administration was the first to accept the potential of regional forums to assist in regional security matters: the George H W Bush administration argued regional security concerns were too complex and diverse to benefit from collective security institutions.

Australia played a role in the formation of the ARF, though less decisively than its role in APEC. Former Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans was one of several regional officials to float a “trial balloon” in the early 1990s, suggesting the idea of a regional forum to address security issues.37 Australia also lobbied US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian Affairs Winston Lord to encourage the United States to overcome preferences for working bilaterally. But Washington’s reluctance had a price. The United States came too late to have a significant influence on the design and development of multilateralism in Southeast Asia, including the development of the ARF in 1993-94.38 Unlike APEC, which was a “hybrid” model, the ARF hewed to ASEAN norms. As Secretary of State Warren Christopher put it in 1995, the ARF operated in the ASEAN way: “consultation, consensus and cooperation.”39

The Clinton administration hoped the ARF would continue to evolve and develop its potential as a forum for security dialogue. Yet it never lived up to these expectations. Gareth Evans reflected in 2014 that the ARF was expected to evolve from “confidence building, to conflict prevention, then conflict management and resolution” but was still “stuck in the first groove.”40 Ultimately, this limited the ARF’s usefulness and corresponding US interest. Michael Green, National Security Council Director for Asia in the George W Bush administration, described the ARF during the mid-2000s as “dreadfully unproductive.”41 Russia’s participation in the ARF, a function of its broader tendency to play a “spoiler” role in Asia,42 also contributed to its atrophy.

Like the ARF, the EAS was also primarily conceived as a forum for political-security dialogue. President Obama attended the EAS in 2011 as a high-level signal about his commitment to the rebalance to Asia.43 However, more substantive justifications were also in play. As Kevin Rudd argued in 2010, regional countries, including the United States, needed to engage China in a constructive dialogue to shape the regional rules-based order and address political, security and economic issues.44 Rudd later argued that the EAS could help “manage” strategic competition between the United States and China because the meetings helped bring leaders face to face. He hoped that the EAS, together with the ARF and ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus), could help develop confidence and security-building measures among the region’s militaries.45

But like the ARF before it, the expectations of the EAS have shrunk. Its summits are largely scripted, with little opportunity or incentive for genuine dialogue among leaders. And when the United States has chosen to use the meetings to encourage pushback against China, it has not always gone over well with ASEAN countries, who during the Trump administration at times perceived US behaviour as escalatory.46 One prominent exception to this rule was EAS leaders’ 2016 adoption of a statement on non-proliferation, urging North Korea to abandon its nuclear and ballistic missile programs.47 The achievement of this statement, requiring consensus from all 18 EAS members, highlights that the EAS can at times be a useful forum for expressing regional solidarity on issues of common concern.

The regional grouping which continues to hold the greatest prospects as a forum for practical security cooperation is the ADMM-Plus. US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin noted in his Fullerton lecture in Singapore in July 2021 that he was proud he and his predecessors had attended every meeting of the ADMM-Plus, describing the grouping as “increasingly central to the regional security architecture.”48 He attended the group’s virtual meeting in July 2021, despite the presence of a Myanmar junta representative. The United States is also an active participant in the seven Expert Working Groups (covering counter-terrorism, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, maritime security, military medicine, peace-keeping operations, humanitarian mine action and cyber security). The practical focus of the ADMM-Plus on confidence-building and capacity-building means it is arguably better suited to current conditions in the Indo-Pacific than other ASEAN-led groupings (see Text box 1).

Official Australian statements continue to suggest that Canberra sees considerable substantive benefit from dialogue and cooperation in forums such as the EAS and ADMM-Plus. In October 2021, for example, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Foreign Minister Marise Payne described the EAS as “the Indo-Pacific’s key leader-led forum to discuss our region’s most pressing strategic challenges.”49 However, such statements overlook the substantial evolution of the regional security environment over the past 30 years and the diminished hopes most countries have for these forums. Ambitious visions of regional leaders sitting down to nut out intractable security issues around the same table appear increasingly outdated. Even so, the Biden administration is right to have identified the ADMM-Plus as a particularly important institution. The United States should look to build on its strong record in this grouping in its Indo-Pacific strategy (see Recommendations).

Text box 1. Cooperation Potential: The ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus)

Five features of the ADMM-Plus:

- Focus on confidence-building and capacity-building

- Focus on crisis management and de-escalation

- Side-stepping some intractable security issues

- Chance for dialogue partners to compete in a positive way

- Opportunity for dialogue partners to cooperate closely with ASEAN countries

Several aspects of the ADMM-Plus make it better suited to the current regional environment than other ASEAN-centred groupings. First, the logic of the ADMM-Plus focus on confidence-building and capacity-building is strengthened — not weakened — by growing US-China competition. Most practically, the ADMM-Plus, like the Shangri-La Dialogue which helped spur its development,50 plays an essential convening role for dialogue and personal contact. Unlike foreign ministers and foreign affairs officials who meet regularly throughout the year in the margins of global and regional meetings, defence ministers and officials have comparatively few opportunities to meet.51 A former military advisor to the US mission to ASEAN described the ADMM-Plus as providing “incomparable” opportunities for the United States Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) to familiarise itself with other countries’ forces,52 providing valuable situational awareness and input into crisis response planning.

Four additional features of the ADMM-Plus make it better adapted for the current regional environment than other groupings like the EAS and ARF. First, many of the substantive decisions of the ADMM-Plus, such as its endorsement of the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea and Guidelines for Air Military Encounters, and the 2021 agreement by members to establish ministerial hotlines, are intended to support crisis management and de-escalation. While experts have pointed to the shortcomings of such mechanisms,53 both the United States and China support crisis management measures as part of their broader regional strategies.54

Second, the ADMM-Plus has found ways to avoid intractable sensitive security issues from derailing its agenda. The ADMM-Plus has not issued jointly negotiated annual ministerial statements since 2015.55 And by dividing its work up into discrete streams within the working groups, it enabled focused discussions to occur concurrently on separate tracks.

Third, the ADMM-Plus focus on capacity building, and the ability of the ‘Plus’ countries to partner with ASEAN on a ‘Plus One’ basis gives the United States the opportunity to compete with China in a ‘bounded’ and productive way. This was illustrated by the separate combined maritime exercises China and the United States hosted with ASEAN in 2018 and 2019 respectively. In undertaking such exercises and other activities through this forum, the United States has a unique opportunity to present itself as a constructive and valuable partner to Southeast Asian countries.

Finally, the Expert Working Groups, which each partner a single ASEAN country with a single external dialogue partner as co-chairs, give countries such as the United States excellent opportunities to collaborate and jointly develop a shared agenda.

4. Shaping Washington’s regional narrative

Although genuine, mutually-beneficial security cooperation in regional forums has become less likely, the United States may, in some circumstances, still be able to use these groups instrumentally to advance its own preferred regional narrative. In this respect, Indo-Pacific institutions are no different to other institutions, like the G7 or G20. This could involve encouraging policy coordination, using regional meetings to declare US policies, or more generally signalling support for regional multilateralism and the rules-based order. Neither the ASEAN-centred institutions nor APEC is well-suited to secure the type of enforceable outcomes the US generally prefers. This has at times led to “more frustration than fruit.”56 Success has also varied over time according to the diplomatic skills and approaches that the United States has brought to bear.

One example of the United States advancing its own objectives successfully in a regional forum was Secretary of State Hilary Clinton’s participation in the 2010 ASEAN Regional Forum. Clinton declared for the first time that the United States had an interest in the resolution of territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Her remarks substantially aided Vietnam’s objective of internationalising the dispute, and ‘cut through’ — not just because of the content, but because they were made in a meeting including the ASEAN countries and China.57 Clinton’s remarks put China on the back foot, with Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi leaving the room for an hour and then returning to give a rambling 30-minute reply, followed up by a statement rebuking the United States for internationalising the issue and claiming support from other delegations.58 Yang was also pushed to a memorable misstep when he told his Singaporean counterpart that “China is a big country and other countries are small countries and that is just a fact.”59 In sum, the episode saw Washington’s regional narrative trump Beijing’s.

Although genuine, mutually-beneficial security cooperation in regional forums has become less likely, the United States may, in some circumstances, still be able to use these groups instrumentally to advance its own preferred regional narrative.

Several other examples demonstrate the scope for the United States to use regional forums to highlight and promote its own priorities. In 2011, President Obama’s attendance at the EAS encouraged all but two ASEAN countries to address maritime security issues in their interventions,60 demonstrating that Southeast Asian countries implicitly rejected Premier Wen Jiabao’s claim that “outside powers” should not get involved with disputes over the South China Sea.61 In 2015, US Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel launched the Obama administration’s Maritime Security Initiative at the Shangri La Dialogue,62 a regional 1.5 track dialogue including a range of regional defence officials, because doing so added impetus and gave the initiative special prominence. Likewise, former Vice President Mike Pence used his address to APEC in 2018 to elaborate on cooperation between Australia and the United States to redevelop the Lombrum naval base in Papua New Guinea.63 In each instance, regional forums helped amplify US regional messaging.

The United States has not always been successful, however, in using regional forums to advance its objectives. Secretary of State John Kerry also tried to use the ARF to highlight concerns about China’s actions in the South China Sea but did not successfully generate enough buy-in from other countries.64 The United States has also periodically tried to use the ARF in support of its approach to Korean Peninsula issues, given that it is the only regional grouping of which North Korea is a member. With the exception of the 2016 non-proliferation statement mentioned above, this has largely been unsuccessful. In 2017, the United States sought to suspend North Korea from the ARF as part of its campaign of “maximum pressure” but did not secure the support of ASEAN to do so.65 The following year, the United States was unable to secure its preferred language on North Korea, resulting in the impression that regional concern about North Korea’s destabilising activities was less than the year before.66

These contrasting examples are illustrative of the opportunities and limitations regional forums present to advance Washington’s regional narrative. They suggest regional meetings provide an important opportunity for declaring US policies, giving countries the opportunity to align with Washington where they judge it is in their interests to do so. But the United States’ inability to get traction on North Korea in the ARF, despite the country’s relative size and isolation, is instructive. Shifting regional positions, especially on issues where China’s interests are directly engaged, will be very difficult. Diplomatic skill in working ASEAN processes makes a difference.

5. “Defensive” interests: preventing China from dominating regional arrangements

Regardless of what can be achieved in practical terms, US engagement remains vital to counter China’s regional influence and prevent China from dominating regional forums. The United States should be cautious about using these forums to counter China overtly — as noted above, the effort to do so during the Trump administration was ineffective. But by maintaining its constructive presence and participation, the United States can indirectly help prevent these groupings from being dominated by China alone — a way of helping to maintain the regional status quo.67

China has a comprehensive approach to advancing its interests in regional institutions. Having overcome initial distrust of the role of regional groupings, by 2007 China participated more fully in regional multilateral forums than the United States, with Washington described as “behind the curve.”68 China’s interest in Asian multilateralism is instrumental, rather than sincere,69 and it has exploited the ASEAN norm of consensus to its advantage on key issues like the South China Sea.70 Beijing has also launched its own Sino-centric Lancang-Mekong Cooperation forum with mainland Southeast Asian countries to advance its Mekong interests, which arguably further divides ASEAN between mainland and maritime countries.71 The United States own Mekong forum, the Lower Mekong Initiative (LMI) was revamped in 2020 as the “US-Mekong partnership,” suggesting that Washington recognised the need to increase the impact and effectiveness of this group.

Even so, China has generally been effective in promoting its own influence and augmenting its bilateral diplomacy, and in 2021 it secured a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” with ASEAN.72 It currently has much more extensive ASEAN engagement than the United States. According to official ASEAN sources, China has more than 60 established mechanisms, including ministerial and officials’ meetings, track two dialogues, memoranda of understanding and plans of action. By contrast, the United States has around 30 such mechanisms. ASEAN’s overloaded calendar of more than 1,500 meetings each year73 means even if the United States now sought new dialogues and meetings, ASEAN may be reluctant to agree for fear of adding further to the burden its members face in servicing the ASEAN schedule.

The early actions of the Biden administration — who attended all key ASEAN-related meetings in 2021, including at the presidential level, indicate officials understand the strategic importance of “showing up.” This is an important course correction from the Trump administration, which neglected this task, despite the centrality of competition with China to its foreign policy.

Concern about vacating the field and leaving China to dominate was a key factor in the US decision to join the EAS in 2011. As noted above, Rudd’s public advocacy focused on the need for regional countries to engage in political-security dialogue with one another. But behind the scenes, the discussion was more sharp-edged. Rudd reportedly told Hilary Clinton that the United States needed to join to avoid a Chinese Monroe doctrine in its near region, and an Asia without the United States.74 This ‘defensive’ point was also made by Australia in discussions with Indonesia. Former Indonesian foreign minister Natalegawa recollects that in a robust informal discussion, “The notion of avoiding a ‘power vacuum,’ the perception of waning US engagement in East Asia and the Asia-Pacific, and the increasing prominence of China were actively discussed.”75

The consequences of even partial disengagement from regional institutions would be strongly adverse to US regional interests. These consequences are demonstrated by the record of the Trump administration, although cannot be fully disentangled from the administration’s broader neglect of regional priorities. Trump travelled for just one APEC and EAS (though he departed Manila before the 2017 EAS leaders’ meeting). He did not send a cabinet-level representative to the 2019 EAS, though it was hosted by Thailand, a US ally, or the 2020 EAS, though Vietnam hosted a virtual meeting, lowering the burden of participation.76 Participation by the secretaries of state and defence was more consistent, though not always well-calibrated to regional sensitivities.

This same period saw a significant decline in regional perceptions of US strategic influence and reliability.77 Though this decline likely has many causes, varying by country, patchy US participation in ASEAN meetings helped cement a regional narrative of US neglect and disengagement. By contrast, China’s much more assiduous attention to regional forums bore fruits. One of the first international gatherings to be convened following the COVID-19 outbreak was a February 2020 ASEAN-China meeting in Laos. This meeting could be scheduled quickly because China was already scheduled to hold a meeting with five ASEAN countries under the auspices of its LMC initiative. China was then able to use this early meeting to help shape international focus away from discussion about the origins of COVID-19 and towards positioning itself as a partner in responding to the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic also saw a re-emergence of the “ASEAN Plus Three,” a meeting of ASEAN countries with South Korea, Japan and China, as a key group for responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. The ASEAN Plus Three, with its focus on practical cooperation and existing stream of cooperation on health, was better placed to respond than the broader EAS, but it is also clear the absence of US leadership was a factor in regional countries’ view of the group as a natural way to respond to the pandemic.78

Extrapolating out from this period of disengagement, the implications for the relative competitiveness of the United States vis-à-vis China are clear. Any US absence would contribute to perceptions of inevitable Chinese regional hegemony. It would diminish the US ability to access regional political leaders and project its messages. It would also fatally wound the logic of inclusive groupings as a place where regional leaders from all countries can meet. China would likely use US disengagement to further diminish the EAS in favour of its bilateral or “Plus One” ties with ASEAN and the ASEAN Plus Three. For Australia, the erosion of the EAS as a premier regional forum would harm Canberra’s ability to project its own influence.

The early actions of the Biden administration — who attended all key ASEAN-related meetings in 2021, including at the presidential level, indicate officials understand the strategic importance of “showing up.” This is an important course correction from the Trump administration, which neglected this task, despite the centrality of competition with China to its foreign policy. It also maintains an important US advantage because China’s leader Xi Jinping has generally not attended regular ASEAN-related summits, instead delegating participation to Premier Li Keqiang.79 However, US attendance may not always be easy. It is fortunate that ASEAN helped facilitate President Biden’s attendance at the 2021 EAS by ensuring that Myanmar coup leader Min Aung Hlaing did not attend.80 But difficult human rights questions will continue to arise, for example, if the United States were to consider hosting a summit with ASEAN, or when countries with poor democratic records host (such as Cambodia, the ASEAN chair in 2022). Hard choices will also arise when inevitable domestic and competing global priorities make travelling to Asia challenging.

6. The “focus” factor: promoting and diversifying Indo-Pacific engagement

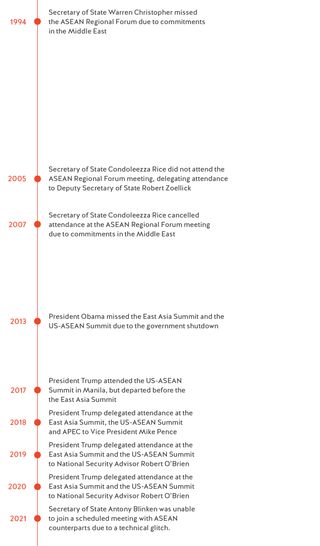

The preceding four sections tracked the evolution of four US interests in Indo-Pacific regional institutions. An additional, enduring benefit should also be considered, which is the way that these meetings can help US administrations focus on the Indo-Pacific. As Michael Green notes, by signing up to the ARF and APEC, the Clinton administration ensured that twice a year US Asia officials would be able to use these meetings to direct resources towards their priorities.81 Given the premium on cabinet-level officials’ time, scheduled regional meetings help compel time and focus in a way that bilateral engagements, which can be shifted or postponed, do not. Avoiding inevitable bad media coverage for non-attendance at meetings has likely helped compel participation: the US Secretary of State has only ever missed three meetings of the ASEAN Regional Forum (see Timeline of notable US absences from regional meetings).

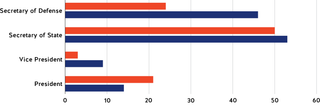

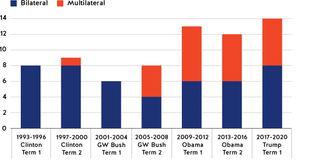

The role of multilateral meetings in driving cabinet travel to the region can be seen in an analysis of the patterns of travel by US presidents and secretaries of state and defence since the 1990s (see Figure 1). Since the Clinton administration, the majority of US presidential travel to Asia was associated with regional meetings. This was especially pronounced during the Obama administration when seven out of 10 presidential trips to Asia were associated with attendance at regional meetings (noting the president would likely have visited more than one country on each trip). During this period, multilateral meetings became a clear driver of additional presidential travel to Asia, likely above the level which would otherwise have occurred.82

Figure 1. Travel trends of US cabinet officials by designation (1993-2020)

Regional meetings have also substantially increased the extent of US Secretary of Defense travel to the region since 2009. This effect held even during the Trump administration when defence secretaries tallied 14 regional visits (more on average per year than the Obama administration), six of these for either the Shangri-La Dialogue or ADMM-Plus (Figure 2). For secretaries of state, who generally travel more frequently than other cabinet-level officials, the effect is weaker. Nonetheless, just under half of the secretary of state’s travel to the region since 1993 has included at least one component related to a regional multilateral meeting.

Figure 2. Secretary of Defense travel by administration terms (1993-2020)

Of course, “turning up” does not necessarily ensure that the United States is devoting additional resources to Asia. And, as Section 4 laid out, its participation has not always been well-calibrated to regional sensitivities. Nonetheless, it is an essential first step. It also enables US officials to connect efficiently with all countries, including those who otherwise would not be a priority for US diplomacy. The opportunity for discreet sideline meetings can be particularly valuable where political or human rights concerns would otherwise prevent US officials from travelling to, or receiving counterparts from, a particular country. For example, Colin Powell famously used the 2002 ARF meeting to meet his North Korean counterpart.83 The message that the United States engages all countries, not just a sub-set who support its regional priorities, also presents Washington as committed to the region for its own sake, not merely for the benefit of US strategic interests.84 This is particularly valuable in the context of the ADMM-Plus, as defence officials have fewer opportunities for regular interaction with their counterparts (see Text box 1).

Australia has long been conscious of the ‘focusing effect’ in its engagement with the United States. Victor Cha, a former Director for Asian Affairs in the George W Bush administration’s National Security Council, argues that both the Howard and Rudd governments valued the Trilateral Security Dialogue (involving Japan as well as the United States) “as a way of engaging the United States and reinforcing bilateral ties, which some felt were being neglected by Washington.”85 This pattern has been repeated more recently in the Quad grouping, which Australia saw as a way of focusing the Trump administration’s attention on the Indo-Pacific. Scott Morrison described the March 2021 Quad leaders’ meeting as “the most significant thing to have occurred to protect Australia’s security and sovereignty since ANZUS.”86 As much as it reflects current Australian concerns about China, it also reflects the importance that Australia has attached to embedding the United States in regional arrangements over the past 30 years.

7. Outlook for the Biden administration’s regional architecture engagement and implications for Australia

The Biden administration has laid a solid foundation for harnessing the potential of inclusive regional institutions in its Indo-Pacific strategy. Like other Quad countries, it emphasises it is committed to inclusive regional multilateralism and the principle of ASEAN centrality in its Indo-Pacific concept. It attended all major relevant regional meetings, in contrast to the Trump administration, which neglected a key tool of influence while simultaneously escalating its rhetorical competition with China for regional influence. The United States has also offered to host APEC in 2023. These actions have built a solid foundation for Washington to use regional institutions effectively to advance its strategic objectives for the Indo-Pacific.

Even so, it is clear the Biden administration sees working with major allies and partners, such as Australia, Japan and India, as likely to deliver greater results than working through ASEAN. This stands in contrast to the Obama administration, which made supporting Asian multilateralism a key pillar of its “Asia pivot.” This preference is reflected in the writings of senior administration officials before taking office. In their January 2021 Foreign Affairs article, Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi emphasise forging flexible coalitions with countries who share US objectives, for example, in balancing and deterring China, or building consensus on aspects of the regional order.87 In his own book, Doshi recommends the United States participate in ASEAN-led bodies at the highest level as part of a strategy to “blunt” China’s regional influence and reduce the likelihood that Beijing-led alternatives dominate.88 This recognition is positive, though underplays the possible positive role participation in these groupings could have for Washington’s regional standing — or in Doshi’s framing, “building American order.”

During her speech in Singapore in August 2021, Vice President Kamala Harris noted the United States was working through “new, results-oriented groups” such as the Quad and Washington’s own Mekong mechanism, as well as with ASEAN.

These inclinations towards narrower like-minded groupings have been borne out by the Biden administration’s focus during its first year in office. During her speech in Singapore in August 2021, Vice President Kamala Harris noted the United States was working through “new, results-oriented groups” such as the Quad and Washington’s own Mekong mechanism, as well as with ASEAN.89 The reference to “results-oriented groups” suggests, at least implicitly, that the Biden administration anticipates few tangible results to come through the region’s broader, inclusive groupings. It is also notable that in 2021 the new administration did not request the elevation of its partnership with ASEAN to a “comprehensive strategic partnership” in order to keep it on equal footing with China’s ASEAN relationship.

This gradual shift towards narrower cooperation with more like-minded countries, rather than broad-based cooperation in inclusive regional institutions, is not specific to the Biden administration but instead reflects the evolving regional environment. As discussed in this report, hopes for genuine political security dialogue have weakened, and forums like the EAS are unable to tackle thorny issues such as the South China Sea. Likewise, the United States’ diminishing interest in regional economic integration has also weakened the substance of what it offers in groups such as APEC.

Despite these limitations, inclusive institutions should remain an important component of US Indo-Pacific strategy. They continue to play an important norm-setting role to establish shared expectations of regional behaviour. This has the potential to help curb China’s regional revisionism and maintain the status quo. In particular, the strength of continued US participation is a firm rebuttal of China’s claim that “outside countries” should not interfere with regional affairs in Southeast Asia.

Regardless of their ultimate contribution to regional security or economic integration, these forums provide unique opportunities for Washington to shape the regional narrative in its favour, to engage regional officials and leaders, and to focus the administration’s time and resources on the Indo-Pacific. If the United States does not use these institutions in this way, China will gain an advantage in the competition to shape the regional order.

Australia’s interest in ensuring a robust US role in Asia remains unchanged over the past 30 years. However, the conclusions of this report suggest that Canberra needs to re-evaluate the way it seeks to engage the United States in regional arrangements. Inclusive multilateral institutions no longer hold the same positive appeal as forums for shared problem-solving or economic cooperation. Australia is already finding new ways to pursue its interests, including through the Quad and Trilateral Security Dialogue with Japan. It should also clearly articulate to the United States the enduring pragmatic case for the United States to use regional forums to augment its own regional influence and compete effectively with China.

In parallel, Australia will also need to plan for the scenario in which the United States does not invest substantial energy in regional multilateral forums. In particular, it is plausible that a future Republican president would share the Trump administration’s disinterest in regional multilateralism. In this scenario, it is likely that exclusive ‘East Asian’ groupings such as the ASEAN Plus Three or new China-led institutions would gain greater currency. These arrangements would diminish Australia’s voice on regional issues, and potentially exclude Canberra from future trade or economic initiatives at a cost to Australia’s economy. In this context, Australia and other like-minded countries may need to invest more in their own participation in ASEAN-related meetings and APEC to demonstrate the continued value and relevance of these forums.

Recommendations

The challenge for the Biden administration is to build on its solid, though not outstanding, record in 2021, by bringing forward a suitable policy agenda in regional institutions to demonstrate its credentials as an indispensable partner. The following recommendations would position the Biden administration to build on the foundation it has laid in 2021.

1. The United States should continue to use the upcoming calendar of ASEAN, APEC and G20 meetings to drive focus, resources and official travel to Asia.

The Biden administration has a notable record of attendance at all major ASEAN meetings in 2021. Its willingness to join summits at the presidential level, when China generally sends only its premier Li Keqiang, should play to its advantage. The United States should attach high priority to continuing its strong record of attendance in 2022, despite likely competing priorities for principals’ time and attention, and possible domestic criticism of ASEAN members’ human rights records. It should nominate and confirm an ambassador to ASEAN as soon as possible. The following meetings will provide important opportunities to develop momentum and drive administration travel and focus to the Indo-Pacific over the next two years.

Key multilateral opportunities to drive US focus on Asia

2022

- Cambodia hosts ASEAN

- Indonesia hosts G20

- Thailand hosts APEC

2023

- Indonesia hosts ASEAN

- India hosts G20

- United States has offered to host APEC (subject to confirmation)

2. President Biden should offer to host ASEAN leaders for a special summit to be held in the United States in 2022 to commemorate the 45th anniversary of dialogue partner relations.

A planned special summit to be hosted by President Trump with ASEAN leaders in March 2020 was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This would have been the second such meeting after President Obama hosted ASEAN leaders at Sunnylands in 2016, successfully raising the profile of his administration’s Southeast Asia engagement. ASEAN’s decision to prevent Myanmar’s coup leader from attending the group’s annual summit in October 2021 demonstrates a workaround could be found to prevent Washington from having to include Myanmar in the gathering. With China’s leader Xi Jinping hosting ASEAN leaders in November 2021, an offer to host this meeting in 2022 would help ASEAN to keep its relationships with the two superpowers on equal footing.

3. The United States should seek to upgrade its partnership with ASEAN to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership by the next US-ASEAN summit, to be held in Cambodia in 2022.

In October 2021, ASEAN elevated its relationships with China and Australia from “strategic partnerships” to “comprehensive strategic partnerships.” Although such designations have few practical consequences, they can inject new energy and help drive diplomatic focus from both sides. Washington, which currently has a “strategic partnership” with ASEAN should seek ASEAN’s agreement to upgrade its partnership to put it on an equal footing with China and Australia in 2022. Myanmar’s membership of ASEAN should not dissuade the United States from taking this step, in particular given the relatively robust sanction applied to Myanmar in 2021 of preventing its military leadership from attending summits.

4. The United States should develop a new flagship initiative to be delivered in partnership with ASEAN, to be announced at the next US-ASEAN Summit.

Currently, two of the administration’s flagship initiatives for the Indo-Pacific — the Quad, and the US-Mekong Partnership, do not involve ASEAN directly. At the US-ASEAN Summit in October 2021, President Biden announced US$102 million for new initiatives on health, climate and trade and innovation. In consultation with ASEAN, the Biden administration should seek to augment such cooperation with a major flagship initiative on a large enough scale to achieve political impact. Energy would be a particularly prospective theme for a major initiative, given its strategic importance, relevance to US interests in addressing climate change, and strong potential for US private sector involvement. ASEAN would value support delivered through ASEAN’s own institutions, rather than “unilaterally” through US regional programs, and that is followed through consistently in coming years.

5. The United States should continue to invest heavily in the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus.

While the United States’ approach cannot neglect any one of the ASEAN-led processes, including the ASEAN Regional Forum, the ADMM-Plus deserves special focus in US Indo-Pacific strategy. Its focus and structure are better adapted to the current regional environment than other groups, and Washington has a strong track record of participation in every ministerial meeting of the group, and having co-chaired an expert working group in all but one cycle since the ADMM-Plus was established. By lending its expertise to the group’s deliberations, the United States can position itself as a constructive and indispensable regional partner, usefully complementing bilateral defence partnerships with Southeast Asian countries. The United States should also use the ADMM-Plus to help encourage deeper defence ties among Southeast Asian countries themselves.

6. In developing its Indo-Pacific economic framework, the United States should avoid undermining existing relevant regional institutions, including the EAS and APEC.

President Biden’s October 2021 announcement that the United States would develop an Indo-Pacific economic framework offered important recognition that Washington cannot afford to neglect economic statecraft in its approach to the region. This agenda provides an important opportunity for Washington to pursue one of its key historical interests in regional institutions. If pursued in partnership with ASEAN, this agenda could inject new energy into regional economic institutions. A willingness to develop part of this agenda through APEC would also signal Washington’s willingness to cooperate with China when it is in the interests of the wider region, which would be welcomed by many countries.

7. Washington should prioritise its relationship with Indonesia, given its current and future influence within ASEAN.

Indonesia is the largest economy and most populous member of ASEAN. It hosts the ASEAN Secretariat in Jakarta and is the only ASEAN member with the potential heft to push the group to take a more assertive posture on key regional issues. Fortuitously, Indonesia is the coordinator of US-ASEAN dialogue relations until 2024 and will chair ASEAN in 2023. This looms as a key opportunity for new regional initiatives, given the relative weakness of recent chairs (Brunei in 2021 and Cambodia in 2022). President Biden’s November 2021 bilateral meeting with Indonesian President Joko Widodo was a positive first step, given that earlier cabinet-level visits to the region did not include Indonesia. While Jakarta will not be willing to align itself with the United States’ broader Indo-Pacific strategy, Washington should treat Jakarta as a pivotal regional middle power and attach high priority to finding areas of common ground and new cooperation with Indonesia within the region’s architecture. This may involve cooperation on issues such as climate change and maritime security.

Selected glossary of Asian regional architecture

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

ASEAN was established in 1967 by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. It later expanded to include Brunei, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia. The United States officially became a ‘dialogue partner’ to ASEAN in 1977. In total, ASEAN has 11 dialogue partners (Australia, Canada, China, the European Union, India, Japan, Republic of Korea, New Zealand, Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom) and convenes several broader regional groupings including the ARF, EAS, and ADMM-Plus.

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

APEC, formed in 1989, aims to enhance regional economic integration. It has 21 member economies — Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, China, Chinese Taipei, Hong Kong-China, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Peru, the Philippines, Republic of Korea, Russia, Singapore, Thailand, the United States, and Vietnam.

ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF)

The ARF, formed in 1994, focuses primarily on regional security cooperation. It comprises 27 members: the 10 ASEAN member states (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam); the 10 ASEAN dialogue partners (Australia, Canada, China, the European Union, India, Japan, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, Russia and the United States); Bangladesh, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Mongolia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Timor-Leste; and one ASEAN observer (Papua New Guinea).

Shangri-La Dialogue

The Shangri-La Dialogue, launched in 2002, is a 1.5 track dialogue convened by the International Institute for Strategic Studies. It provides a platform for government ministers, business leaders, and security experts to debate Asia’s pressing security challenges, develop new approaches, and engage in bilateral discussions.

East Asia Summit (EAS)

The EAS, formed in 2005, is a leaders-led forum that focuses on strategic political and security issues. It has 18 members: the 10 ASEAN countries (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) along with Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, Russia and the United States. The United States joined the East Asia Summit in 2010 and first attend at the presidential level in 2011.

ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meetings Plus (ADMM-Plus)

The ADMM-Plus, formed in 2010, is a defence ministers-led forum that aims to strengthen regional security and defence cooperation. It has the same membership as EAS: the 10 ASEAN countries (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) as well as Australia, China, India, Japan, Republic of Korea, New Zealand, Russia and the United States.

G20

The G20, which has met annually at leaders’ level since the global financial crisis in 2008, is a global multilateral forum for economic cooperation. Its members include several Indo-Pacific countries including Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Republic of Korea, and the United States. The Chair of ASEAN is regularly invited as a guest of the chair. Other members are: Argentina, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the European Union.

Quad

The Quad is a diplomatic grouping comprising the United States, Australia, Japan and India. The Quad met at leaders’ level for the first time in 2021. Quad senior officials have met regularly since 2017, and Quad foreign ministers have met three times since 2019. Areas of Quad cooperation include COVID-19 vaccines, critical and emerging technology, combatting climate change, infrastructure, cyber, the sustainable and stable use of outer space, and cultivating next-generation STEM talent.

Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)

The CPTPP is a free trade agreement signed by 11 countries in 2018: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam. It is a successor agreement to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement which also included the United States. The Trump administration withdrew from the TPP after it took office in 2017.

Turning up: Timeline of notable US absences from regional meetings