Key points

- Because of the substantial policy autonomy and legal independence of American states, the outcome of state-federal conflicts will shape the Trump administration’s policy impacts and legacy, especially in areas such as environmental/climate change policy, immigration and marijuana legalisation.

- The execution of Trump administration policies on climate change and undocumented immigration will largely depend on legal challenges from Democratic state governments.

- A group of progressive and conservative states has been successful in convincing the Trump administration to abandon marijuana prosecutions in states, allowing medical or recreational use.

- The next Supreme Court appointee will play an important role in determining how a range of lawsuits contesting the administration’s policy agenda are settled.

- Australia should focus on potential partnerships and common areas of concern with US states, rather than simply relying on diplomatic engagement with the White House.

- There are opportunities for Australian jurisdictions to pursue climate partnerships with US state and city officials, in lieu of US federal government action.

The polarisation of American politics

Partisanship has become the dominant driver of social and political conflict in the United States.1 Not only are there now “substantial differences in political perspectives [among voters] across a single ideological dimension”, moderates have become a minority, albeit a substantial one.2 According to a 2017 Pew poll, 86 per cent of Americans believe partisanship is a “strong” or “very strong” source of societal conflict. Only 65 per cent regard race and 60 per cent regard economic inequality in the same terms.3 A range of developments explain how we got here: increasing public polarisation starting in the late 1960s, the bruising tactics pioneered by House Speaker Newt Gingrich during the 1990s and the recent rise of populist dissent in both political parties. The most ideologically-charged segments of the public are now also the most politically active.4

Partisanship in the United States has become increasingly affective — driven by increased feelings of dislike toward those in the opposing party, rather than simply by disagreement with their views.5

Because of the substantial policy autonomy and legal independence of American states, the outcome of state-federal conflicts will shape the Trump administration’s policy impacts and legacy.

In this context, substantial polarisation has emerged between solidly Republican and solidly Democratic states. State-federal relations are increasingly conducted in the same vituperative style as Capitol Hill partisanship. This will have significant implications for the Trump administration’s policy agenda because the states have substantial powers to enable or obstruct federal policy, as well as a significant degree of policy autonomy in some areas.

Policy and legal interventions by states are critical because many of President Donald Trump’s major policy objectives, such as restricting immigration and winding back Obama-era policies on healthcare, climate change and economic regulation, can be partially or substantially advanced by the president without congressional action. Direction of the agencies and departments within the Executive Branch — the administrative arm of the federal government — is an important presidential lever of power that can be used to bypass Congress. But the states have ways to block, alter and work around federal policy as well. Hence, the so-called “blue” Democratic states are contesting and countering policy initiatives of the Trump administration, whereas Congress seems unable or unwilling to play this role.

American federalism: The political and legal context

State-federal tensions are nothing new in the United States, but the dynamics have shifted in at least two important ways since the 2016 election.

First, while Republican-dominated states played a consequential role in obstructing key Obama policies, Democratic states are now presenting states’ rights as a vital legal principle and a safeguard of American democracy. Ironically enough, conservatives have traditionally endorsed state autonomy as a check on overweening federal power, whereas liberals have regarded federal initiatives as an important vehicle for advancing progressive goals. In the Trump era, liberals are appealing to states’ rights, while a Republican administration is asserting federal authority to pursue conservative goals such as environmental de-regulation.6

Second, while tensions between the Executive Branch and Republican states were certainly lively under Obama — lawsuits brought by the states against the Affordable Care Act are a case in point — the state-federal disagreements over the Trump administration’s policies are even more contentious, both at the rhetorical level and in the volume of lawsuits generated.7 Since most of these contests will ultimately be settled in the courts, Trump’s ability to secure his preferred nominee as the next Supreme Court justice will determine how fully his administration’s policy agenda is implemented.

States and the Constitution |

|

State-federal relations are governed by two key constitutional provisions: Article 6, or the Supremacy Clause, which asserts that federal law supersedes and pre-empts state law, and the 10th Amendment granting to the states all powers not explicitly given to the federal government. During the 20th century, the federal government used the Supremacy Clause to greatly expand the number of issues that federal laws and regulations address. The 10th Amendment has been subject to a more ad hoc, “situational” set of interpretations over the years.[^8] Federal legal judgements such as 1997’s Printz v. United States establish that the states are under no obligation to enforce federal law even in areas where federal law pre-empts state law, however. Coerced enforcement in such instances is deemed to be an illegal “commandeering” of state resources. The current dispute over undocumented immigration will test the notion that forcing states to comply with federal deportation priorities amounts to commandeering. The federal power to regulate commerce among the American states (Article 1) also has bearing on the independence of the states. The Commerce Clause was the basis for the decision in 2005’s Gonzales v. Raich, a controversial judgement against California’s medical marijuana law. The federal government can also use its spending power to attach conditions to federal funds in order to compel the states to fall into line with federal law. Trump has repeatedly threatened to use this lever to enforce immigration policy. On the other hand, states can request exemptions and waivers from federal regulations in order to craft their own regulatory standards. Since the 1970s, for example, California has relied on waivers within the Clean Air Act so that it may impose tighter regulations on smog and, more recently, on automotive greenhouse gas emissions. State governors and city mayors have even worked around the Executive by pursuing quasi-diplomatic international partnerships in the climate change area. |

Undocumented immigration, sanctuary states, and the Trump agenda

Preventing undocumented immigration is one of Trump’s most important and longstanding priorities. Trump has so far failed to secure funding for his most controversial campaign pledge — the US-Mexico border wall — but he has increased funding for border security, with 25 per cent more individuals apprehended as candidates for interior removal (apprehension away from the border) in 2017 over 2016.

The administration’s guidance to the Department of Homeland Security, which administers border control, has also curtailed the Department’s discretion in enforcing deportation orders. This so-called prosecutorial discretion in deportations began with the Carter administration.9 While the Obama administration advised federal agencies in 2013 that discretion could be exercised for “humanitarian factors… length of time in the United States, family and community ties in the United States”, the Trump administration revoked this instruction, more than doubling the number of arrests of undocumented immigrants without criminal convictions.10

The sanctuary movement in relation to immigration began in early 1980s, when cities across America enacted policies sheltering refugees from Central American civil wars.11 One of the current concerns driving the sanctuary movement today is that undocumented immigrants will not come forward as witnesses or victims of crimes without a trusting relationship with local law enforcement. Recent data on domestic violence reports in Texas reflects the validity of this concern.12 Sanctuary policies can be enacted at state, county and city levels. Local officials at each of these levels can instruct their officers not to ask members of the public about their immigration status, not to share certain information about the undocumented with federal officials, etc.13 Sanctuary city jurisdictions can be found across the United States, even in Republican strongholds such as Alabama and Kentucky.

Officials at state, county and city levels can instruct their officers not to ask members of the public about their immigration status and not to share certain information about the undocumented with federal officials.

State-level responses to the Trump administration’s immigration policy vary greatly, with several red states and cities serving as enablers of federal policy. Shortly after Trump issued his first executive orders on immigration in February 2017, Florida’s Miami-Dade County reversed sanctuary policies that had barred the county from using local funds to assist federal immigration authorities.14 Despite a state ban on sanctuary cities since 2015, in 2017 North Carolina indicated that it would withhold state funds from cities deemed simply “soft” on immigration enforcement.15 Iowa passed a similar measure last April16 and Texas banned sanctuary cities in May. Texas and Arizona have also responded enthusiastically to Trump’s call to station military forces on the US-Mexico border, with both states supplying National Guard troops to assist Customs and Border Patrol.

The Department of Homeland Security also maintains 287(g) agreements with 76 law enforcement agencies in 20 states.17 Jurisdictions across Texas, including the Texas state legislature, have been especially receptive to these agreements, which deputise local law enforcement to undertake immigration enforcement including detaining persons suspected of violating immigration laws in local jails.18 While a handful of local jurisdictions in blue states such as New York and Massachusetts have signed 287(g) agreements, none have in California. But even there, the administration’s policies are supported by some local governments. Orange County filed a brief in support of the Trump administration’s lawsuit against California’s sanctuary policies, and Orange County law enforcement has been instructed not to comply with the state of California’s sanctuary policies.19

Progressive-leaning states, including California and Illinois under moderate GOP governor Bruce Rauner, have responded to the Trump administration’s immigration agenda by shoring up or extending their sanctuary status. With no action at the federal level to clarify the status of the so-called Dreamers — individuals brought illegally to the United States as children — states including New York, Maryland, Indiana, California and Illinois have sought to preserve what protections they can for this group, for example by maintaining drivers’ licences, continuing to provide professional licenses for employment, or continuing to provide in-state college tuition. Illinois’ Trust Act of August 2017 limits the ability of law enforcement to cooperate with federal authorities.20 The city of Chicago was the first jurisdiction to sue the federal government after Attorney General Jeff Sessions threatened to withhold federal grants to the city over its sanctuary policies, and it did so successfully.21

The city of Chicago was the first jurisdiction to sue the federal government after Attorney General Jeff Sessions threatened to withhold federal grants to the city over its sanctuary policies, and it did so successfully.

California has both the largest undocumented population in the United States and some of the nation’s strongest sanctuary laws. Although many Californian cities already had sanctuary policies in place, in 2017 the state legislature passed additional measures: to limit law enforcement cooperation with federal authorities; to prohibit employers from sharing employee information without a court order; and to limit contact between state and local prisons and federal immigration authorities. In response, and citing law and order concerns, Trump attempted to cut federal funds to Californian cities and the Department of Justice announced a lawsuit against the state, claiming that all three state laws are in violation of federal statutes.22 In July 2018 a federal judge ruled in favour of California, except in the case of a narrow point of labour law,23 but it remains to be seen whether the Department of Justice will pursue new legal avenues against sanctuary policies.

Two issues stand out in the Trump-California standoff over immigration. Sessions’ lawsuit will clearly set important legal precedents for states’ rights and commandeering and will have significant bearing on whether the Trump administration’s immigration policy will be fully implemented. Trump’s repeated criticisms of California’s policies also continue to inflame the more emotionally-charged and polarising subjects in American politics today.

Environmental regulation and climate change policy

Trump’s longstanding environmental policy prioritises winding back or narrowing environmental regulations, reducing the mandate and funding of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord — goals that can all be accomplished without Congress. The appointment of anti-EPA crusader Scott Pruitt to head the agency was an important symbol of this agenda. Pruitt’s recent resignation amid ethics scandals is unlikely to bring about any alteration to the administration’s policy agenda, however.

In June 2017, Trump announced the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris agreement. The following October, leaked documents revealed administration plans to scrap the Obama-era Clean Power Plan, which limits CO2 emissions in US power generation. Climate change is no longer listed as a threat under the latest National Security Strategy and has been expunged from other Trump administration documents, such as federal emergency management plans. The administration has also lifted regulations on hazardous air pollutants and pesticides, and has announced plans to open up the entire US coastline, with the exception of waters around Florida, to oil drilling.

As with immigration policy, a number of US states have welcomed this de-regulatory environmental policy. There is wide variation in environmental attitudes in the United States: 70 per cent of Vermont residents and 68 per cent of Hawaiians regard environmental regulations as “worth the cost”, but in West Virginia and Wisconsin only 38 per cent do.24 South Carolina has the United States’ lowest renewable energy target: 2 per cent of power generation by 2021.25 By contrast New York, one of the nation’s renewables leaders, has a target of 50 per cent by 2020. Twenty-four red states sued the Obama administration over the Clean Power Plan, and will presumably welcome its demise, although several Democratic states have indicated that they will counter-sue to keep it. South Dakota, Kentucky, Arizona and Indiana, among others, have passed laws that in various ways prevent state agencies or future legislation from imposing any environmental regulation that is stricter than federal baselines.26

Given the size and economic clout of many US states, as well as the fact that utilities are controlled at the city or state level, climate is an area in which subnational US jurisdictions can have a substantial impact on emissions.

Environmental regulation is an area in which the states have some autonomy by filling gaps in federal regulation or outpacing federal standards. Given the size and economic clout of many US states, as well as the fact that utilities are controlled at the city or state level, climate is an area in which subnational US jurisdictions can have a substantial impact on emissions. Several US states acted independently to reduce emissions after the George W. Bush administration withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in 2001. New Jersey had adopted Kyoto targets in 1998 and retained them after 2001. It also initiated a carbon trading agreement with the Netherlands — the first such agreement between a US state and a foreign government on climate change.27 Other states, such as Massachusetts and Oregon, imposed more stringent emissions standards on power generation in response to Bush’s withdrawal from Kyoto.

These moves set the stage for a wave of independent climate policy by the US states. California, which had set its own standards on car exhaust since the 1960s to address Los Angeles’ infamous smog, initiated a CO2 cap and trade framework in 2005 and set targets to lower emissions with the Global Warming Solutions Act in 2006. Following New Jersey’s lead, California initiated a cap and trade market with several Canadian provinces, known as the Western Climate Initiative, which California now cites as a framework for meeting the Paris targets.28 In 2007 New Jersey adopted a 20 per cent reduction target for greenhouse gas emissions by 2020. These targets are not only ambitious, they are also achievable: New Jersey and California have both already reached their 2020 targets.29

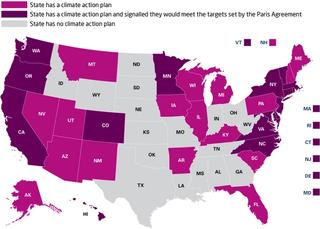

There are also several multi-US state climate agreements in place that predate the Trump administration, notably 2009’s Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, which established a cap and trade system and clean energy investment fund covering nine north-eastern states.30 In both the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and the Western Climate Initiative, large markets such as California and New York play an integral role in making cap and trade viable for smaller jurisdictions. With these frameworks in place, many states and cities were well-placed to announce that they would maintain climate progress when Trump was elected. Thirty-four states have climate action plans and 14 states led by California, New York and Washington signalled they would meet the Paris goals as part of a new US Climate Alliance.31 The alliance has now expanded to 16 states and Puerto Rico, almost all led by Democratic governors, and aims to play a role in sharing best practices on the international stage.

US states that have a climate action plan

Trump has recently indicated that he will relax the current engine efficiency standards for private vehicles. Since the 2000s California has adopted some of the most stringent targets in the world, a policy that depends on the same federal waivers that allow the state to more stringently regulate smog emissions. Fourteen states opted into California’s strict mileage standards. Border states with dealerships selling California-compliant cars, for instance, found it economically viable to do so. But a number of north-eastern states also adopted the standards as part of broader sustainability commitments. About 130 million Americans were thus covered by Californian vehicle efficiency standards when the Obama administration adopted them nationally in 2011.32 In April 2018, Pruitt announced that the current target of 54 miles per gallon by 2022-2025 would be scrapped, citing opposition from the auto industry. Acting EPA head Andrew Wheeler announced in August that he intends to revoke California’s waiver to set its own standards for car efficiency, which filed a lawsuit to maintain the waiver the same day.33 Other states are expected to join the suit, whose outcome will be significant both in terms of how much state policies can contribute to global greenhouse gas targets and in maintaining confidence in international climate agreements despite Trump’s position.

Marijuana legalisation

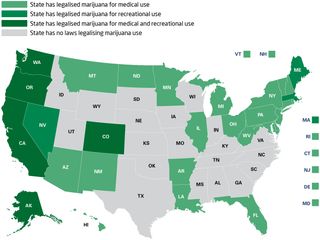

Thirty US states and the District of Columbia now allow marijuana for medical and/or recreational purposes, a group that includes red and red-leaning states such as Arizona, Ohio, Florida and Colorado. Vermont recently became the first state to legalise recreational marijuana by legislation instead of popular ballot. State laws allowing the cultivation, sale and use of marijuana for either recreational or medical purposes directly conflict with the federal Controlled Substances Act of 1970, however, which classifies marijuana as a drug with high potential for abuse and no known therapeutic value. While the Supreme Court ruled in the 2005 Gonzales case that the federal government could override state laws and prosecute anybody engaged in the supply or use of marijuana, this has not occurred on any significant scale in states that have legalised.

US states that have laws broadly legalising marijuana in some form

Federal capacity to enforce marijuana laws is severely limited by the fact that the federal Drug Enforcement Agency only employs 4600 agents.34 The vast majority of illicit substance enforcement is done by state and local police. The Obama administration issued instructions to the Department of Justice not to pursue enforcement of marijuana laws in legalised states. Since 2014 Congress has attached so-called “Rohrbacher-Farr” riders to its annual spending bill to protect medical marijuana users. There is also strong public support for marijuana legalisation with 61 per cent of Americans supporting full legalisation, including a majority of Republicans.35 Even Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ own home state of Alabama filed an amicus brief in Gonzales supporting the right of states to set their own marijuana policy.

Trump has repeatedly shifted his position on marijuana. During the campaign Trump stated that he “100 per cent supported” medical marijuana and believed recreational cannabis should be for states to decide.36 Sessions, however, has been strongly opposed to all forms of marijuana legalisation for some time. After taking office Trump backed Sessions’ call for a federal crackdown on recreational marijuana legalisation. In January 2018 Sessions rescinded Obama’s instructions and requested that Congress also rescind its Rorhbacher-Farr riders, stating that he was restoring the rule of law.37 Any federal case against the states would rely on Gonzales, while states would likely oppose any efforts to utilise state resources in enforcement on the grounds of commandeering.

As a result of a lack of support for a marijuana crackdown from prominent Republican politicians and Republican voters, in April the White House announced that the president would not pursue Jeff Sessions’ war on marijuana.

But these tentative moves against the states have faced a critical obstacle: a lack of support from red states in general and outright opposition from prominent Republican politicians38 such as Nevada Senator Dean Heller, Nevada Governor Brian Sandoval, and Colorado Senator Cory Gardner. The latter announced in January that he would hold up all of Trump’s judicial appointments in the Senate until the administration safeguarded the recreational marijuana policies of Colorado.39 As a result of this pressure and a lack of support for a marijuana crackdown even among Republican voters, in April the White House announced that the president would not pursue Sessions’ war on marijuana. According to Gardner, Trump went further than this, offering an assurance that he would seek federal action to safeguard states’ rights on marijuana policy. In June Trump announced that he may support a bipartisan bill sponsored by Gardner preventing marijuana prosecutions in legalised states. How durable this commitment is remains to be seen, but with the Gonzales precedent in place, states may have few legal avenues to block a federal crackdown on recreational or medical marijuana should Sessions once again find himself setting the administration’s agenda.

Conclusion

Implications for the United States

The implementation of critical components of the Trump administration’s policy agenda, and thus Trump’s overall legacy, depends to a significant degree on lawsuits now underway with many blue states. These decisions will also set important legal precedents for states’ rights.40

Immigration, environment and marijuana policy are currently the most prominent areas of disagreement between the states and the Trump administration but new fault-lines could open up around issues such as tax, welfare, industrial relations, healthcare, and LGBT rights, depending on the directions taken by the Trump administration. The Republican Party’s failure to repeal the Affordable Care Act may ultimately see the states striking an even more diverse set of positions on healthcare: single-payer for California as has been proposed, and perhaps circumscribed plans with no individual mandate in red states.41

The current Supreme Court vacancy brings added uncertainty to the process. Anti-choice conservatives have endorsed Trump’s Supreme Court nominees based on the expectation that they would help overturn the landmark decision Roe v. Wade and place the issue with the states.42 The administration has a strong interest in appointing a judge that with a robust view of executive power in order to protect the president from the Mueller investigation. Yet a new, conservative-majority Supreme Court may be faced with some critical distinctions to parse in considering whether conservative reasoning in favour of states’ rights in the case of abortion should also be applied to progressive objections to federal policy on issues such as environmental standards or immigration.

A diversity of legal and policy conditions in the states could better accommodate the diversity of the country itself, and liberals and conservatives would “have less to fear from opponents’ victories at the national level”.

A conservative-majority Supreme Court would likely support scrapping the Clean Power Plan and other moves by the Trump administration to limit the regulatory work of the EPA but it’s less clear where it would land on marijuana and immigration.43 Regarding marijuana, it is noteworthy that a generally conservative disposition to support Article 10 does not automatically suggest support for recreational or legal marijuana in the states, given the unambiguous fact that marijuana remains illegal within federal law.

Some conservatives argue that broader values are at stake in these decisions and in the political dynamics of federalism. A diversity of legal and policy conditions in the states could better accommodate the diversity of the country itself, and liberals and conservatives would “have less to fear from opponents’ victories at the national level”.44 This understates the cynical way that states’ rights arguments are often used, and it elides the question of which legal and policy questions demand a uniform national policy. Legal questions around federalism are likely to remain divisive, rather than alleviating partisanship and diversity.

Implications for Australia

Australian audiences should bear in mind that a range of legal disputes between the states and the federal government could have significant bearing on the implementation of the Trump policy agenda. This needs to be taken into account in assessing what Trump’s domestic legacy may be. There are also several diplomatic and policy implications that Australian policymakers might bear in mind, particularly in regards to climate change:

- While the withdrawal from Paris may be largely symbolic, the dismantling of federal regulations will tangibly affect overall US progress toward reduced emissions.

- Despite this, there remains a very large market for renewable energy technologies in states that maintain their own ambitious emissions targets, creating opportunities for Australian businesses.

- There are numerous opportunities for Australian jurisdictions to pursue climate partnerships with state and city officials in the United States.

- The legalisation of recreational marijuana in US states provides a range of different regulatory and taxation models in the event that such a move be considered by the Australian government.

- Overall, the policy autonomy afforded to US states and their ability to impact on the execution of Trump administration policies should inspire better relations and potential partnerships between Australia and US states, rather than relying on traditional engagement with the US federal government.