Key takeaways

- The burden of the COVID-19 recession is falling most heavily upon low-paid personal and household services occupations where businesses have been forced to close. The impact is most severe on women.

- It is a completely different pattern to the Global Financial Crisis where, in the United States, it was middle-income earners who lost out and whose jobs never returned.

- It is also different to Australia’s last recession in the early 1990s, when it was construction, manufacturing and farming jobs for men that fell furthest. The job losses in manufacturing and agriculture were permanent.

- The past two decades have brought big growth in services industries, with business services paying above average wages and personal services paying below average.

- The impact of the COVID-19 recession is reduced for those able to work from home, including many in the business services sector, but few in the household services.

- Preliminary indicators from employment service, Seek, show that in Australia, low-paid positions within the low-paid sectors have had the biggest fall in employment.

- US surveys show that women and those without tertiary education are suffering the biggest job loss.

- The experience of past recessions is that unemployment rises rapidly in a recession but takes a long time to fall.

Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis is having unequal impacts on the labour force with low-paid workers suffering the most.

The forced shutdowns have halted the delivery of most personal services, which had been the major source of growth in employment for lower-skilled and lower-paid workers over the past decade. Business services — which have been the other major avenue of employment growth since the Global Financial Crisis and which favour high-income earners — have also suffered, with the collapse in demand spreading through most corners of the economy. Yet at the same time, a significantly larger share of business service workers has been able to continue working on screens from home.

One of the big labour force trends of the last few decades has been the polarisation of the labour force. Middle-income jobs performing routine tasks are increasingly scarce amid increased employment at both the top and the bottom of the income spectrum. The COVID-19 crisis is eroding the jobs at the bottom.

The COVID-19 crisis is having unequal impacts on the labour force with low-paid workers suffering the most.

The official labour force surveys will take time to trace the uneven occupational and industry impacts of the crisis. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) first full labour force report on the occupational and industry impacts of the downturn will not be published until 26 June while, in the United States, the Bureau of Labour Statistics will release its employment report for April on 8 May.

Yet trends are already emerging from the ABS’s new payroll survey and from the US agency’s March survey.

The ABS survey, which is based on payroll data collected by the Australian Taxation Office and published 20 April, shows that in the three weeks after the first 100 cases of coronavirus were registered, the hospitality industry shed 26 per cent of its workforce, or 240,000 workers, while the recreation and arts industries lost 19 per cent, or 47,000 workers. These estimates are likely conservative as only 70 per cent of small businesses are registered with the ATO payroll system. Both industries are among the lowest paid, with average weekly incomes of just A$638 in the hospitality sector and A$989 in hospitality and the arts. The survey shows retail, which is also low paid, to be one of the least affected, with employment down just 2.7 per cent, however this likely reflects the disparate performance of the grocery sector which faced a surge of panic buying and general retail sectors like clothing which have faced widespread shutdowns. It likely excludes many small retailers not registered on the ATO system.

Figure 1. Job losses and average incomes in Australia, by sector

Other industries have been directly affected by the shutdown. Mining, which is Australia’s highest-paid industry, has suffered an 8.4 per cent contraction in employment equivalent to 20,000 positions — likely reflecting the suspension of “fly-in-fly-out” arrangements, as well as the closure of some operations in remote areas with high indigenous populations.

The ABS survey shows that women have suffered a bigger percentage fall in employment, with gender gaps of between two and four percentage points in the hospitality, recreation and arts, utilities, transport and general services sectors. The fall in employment has also been steepest at about nine per cent for people aged either under 30 years or over 70 years.

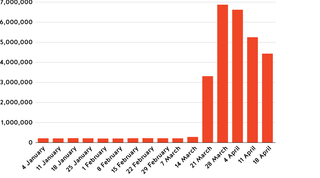

The weekly US reports of claims for unemployment benefits revealed the massive and immediate impact of the crisis. New unemployment claims have jumped from a long-standing average of 215,000 per week to a weekly average of 5.25 million claims since 21 March. The total since that date has reached 26.2 million, or approximately 16 per cent of the workforce.1

Figure 2. Weekly unemployment claims in the United States, January-April 2020

The cumulative total wipes out the entire 22.8 million jobs generated in the United States in the decade since it emerged from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Initial unemployment claims are usually a bit higher than the final estimate as people find alternate work before benefits are paid, however, the wave of job losses is continuing with many claims yet to be processed.

The March US labour force report, which only captured the first two weeks of the month, showed a fall of three million in the number of people employed since the middle of February.2 Of the positions lost, 88 per cent of the jobs were in sectors paying below-median salaries with a third in sectors paying 75 per cent of the median wage or less.3 Industries paying above medium wages accounted for only 12 per cent of the job loss.

How the last recessions hit

Every recession leaves a distinctive mark on the labour force. Following the GFC, when unemployment rose to 10 per cent in the United States, there were unusually large numbers of job losses in the finance and business services sectors as well as big falls in construction and manufacturing.

American construction and manufacturing jobs eventually returned but there was a permanent loss of middle-skilled jobs paying average wages as the labour market became more polarised. This trend has been gathering strength in the US labour market since the 1990s but was particularly savage during the GFC.

The jobs that were disappearing even before the pandemic hit include clerks, cashiers, telemarketers, book-keepers and insurance underwriters. While these jobs typically required completion of school and often some form of further certificate training, they have been particularly susceptible both to automation and outsourcing.4 They accounted for 94 per cent of all jobs lost in the 2008-9 recession. Their share of employment dived 11.8 per cent during the crisis and has fallen a further 3.9 per cent since.5 Nearly all these positions were in the services sector. By contrast, one analysis shows that less than two per cent of the positions lost in the United States in the GFC were from the lowest-paid sectors.6

Australia’s last two major recessions in 1981-3 and 1989-91 both resulted in the loss of more than ten per cent of jobs for male workers in the farming, manufacturing and construction industries.7 In both manufacturing and agriculture, many of those job losses were permanent, with a large cohort of men in their mid-40s and early 50s migrating from unemployment benefits to disability pensions before becoming eligible for the age pension at age 65.8 Manufacturing now employs only 7.1 per cent of the labour force in Australia — half its share at the time of the 1989-91 recession — while agriculture’s share has dropped from 5.6 per cent to 2.5 per cent.

Polarisation of the labour force — with growth in employment at the top and bottom ends of the income distribution — has occurred in Australia and the United States. Since 2008, employment of clerical, sales, technical, and labouring workers in Australia fell considerably amid an increase in jobs in community and personal services and management.9 One study found the phenomenon was most marked between the mid-1980s and the early 2000s.10

The divided services sector

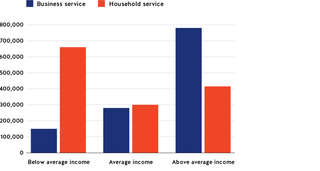

Australia’s services sector has been the big winner since the country’s last recession, with its share of employment rising from 71.5 per cent to 79.4 per cent from 1991 to 2019. Reserve Bank analysis divides the services sector into two groups: business services and household services.11

Business services added 1.2 million workers since 2000, of whom almost two-thirds receive above-average wages while only 12.5 per cent earn below the average.

Household services added 1.4 million workers over that period among whom almost half are earning below-average wages and only 30 per cent earning above average.

Figure 3. Services jobs growth in Australia, 2000-2017

Few sectors of the economy, apart from public service, are untouched by the COVID-19 crisis, which has had two broad impacts, with the initial forced shutdowns followed by a sharp fall in demand.

Many household services have had to close because they are deemed non-essential and involve face-to-face contact. Hospitality and travel are the two most obvious, although there are many other household services similarly affected.

Few sectors of the economy, apart from public service, are untouched by the COVID-19 crisis, which has had two broad impacts, with the initial forced shutdowns followed by a sharp fall in demand.

One major bank which provides terminals to process health insurance claims for health services other than medical practices records that transaction volumes are down by 90 per cent. Business has stalled for health services from dentists to physiotherapists and podiatrists. Although employment in the health sector is down by only 2.5 per cent, based on the ABS payroll study, it is the largest employer and that represents the loss of 45,000 positions.

The other impact is the collapse in demand as households, businesses and their bankers lose confidence. This has spread broadly through the economy as discretionary spending by both business and households is frozen.

Practically no one is commissioning architects to plan new buildings or booking a new advertising campaign while new business investment has stopped and even transport services have slowed as spending across the economy declines. The ABS shows the loss of 7.9 per cent of professional positions, equivalent to about 92,000 jobs.

Few are entirely unscathed, although a government job remains a relatively secure shelter from the storm.

Recruitment shows unequal impact

The employment marketplace Seek provides an insight into the shock being delivered to the Australian labour market. In the week to 12 April, the volume of job postings was down 69 per cent, relative to the same week last year.12 Like the ABS payroll survey, it shows job advertising was down heavily across all industry sectors. The biggest falls were in recreation, office support, hospitality/tourism and retail where the volume of job postings dropped by 80 per cent or more. These are all among the lowest-paid industries.

The survey provides indirect evidence that within the lowest-paid industry sectors, it is the lowest-paid positions that are being lost. With fewer low-paid jobs being advertised, the average salaries of the remaining job postings in these sectors are higher.

New job postings in the hospitality sector in March, for example, had an average salary of A$67,520, which was 6.8 per cent higher than in the same month last year. Before the crisis, hospitality postings were showing an average salary of A$64,367, which was annual growth of only 2.7 per cent. It is not that there is a surprise burst of wage inflation in hospitality, but rather that the average has been skewed by all the low-paid positions dropping out.

Across most of the low to medium-pay sectors, average salaries of the jobs advertised in March were considerably higher than before the crisis because lower-paid positions are no longer being advertised.

This trend is not evident everywhere. In management consulting, for example, the pre-crisis average salary was A$113,640 which was 2.3 per cent higher than the average a year earlier. However, the March figures are showing a 2.9 per cent salary drop. This suggests that at the top of the income spectrum, the highest-paid positions are not being posted.

However, across most of the low to medium-pay sectors, average salaries of the jobs advertised in March were considerably higher than before the crisis because lower-paid positions are no longer being advertised. Two mid-salaried sectors showing this trend are human resources and marketing. With demand falling across the economy and businesses looking for savings, the lower-paid staff in these business services are seen as more dispensable than their managers.

The United States highlights the role of gender and education

Several academic surveys in the United States are endeavouring to fill the gap before official data becomes available. One large survey, canvassing a total of almost 17,000 respondents in both the United States and the United Kingdom, found that women and workers without a university degree were significantly more likely to have lost their job.13 Women in the United States were seven per cent more likely to have lost their job than men, while those without a degree were eight per cent more likely. The need to care for children unable to attend school coupled with entrenched gender roles may partly explain the higher share of women reporting unemployment, though women are also more heavily represented in lower-paid occupations.

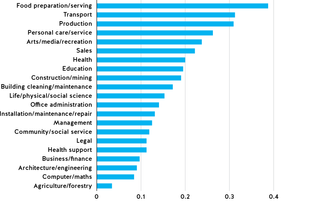

A key indicator is the ability to work from home. The US occupations with the highest likelihood of job loss are food preparation and serving, transport and material moving, production, and personal care and service, where few tasks can be performed from home. The more secure sectors include information technology, engineering and architecture, business and finance operations and healthcare support. Farming, where the home is the work, is the most secure.

Figure 4. Probability of job loss in the United States due to COVID-19

Even within sectors, the ability to perform tasks from home explains 69 per cent of the variation in job loss across occupations. The US study found no significant relationship between job loss and age although, in an Australian context, the average age of people in many of the personal service occupations is in their early 30s.14

What is the road back?

Another US survey shows that many of those losing their jobs are not looking for another position — likely indicating that many are opting for early retirement.15 Although it indicates that the number losing jobs is higher than indicated in the unemployment claims, it suggests the level of measured unemployment may be lower than the 20 per cent-plus forecast by many economists because people are dropping out of the workforce altogether.

In Australia, the share of the population either in work or seeking work was at close to record levels ahead of the crisis, partly because more people aged over 65 years were continuing to work. It is likely many of this cohort will not return to the labour force.

While there is a political push both in the United States and Australia to “get back to work”, the experience of past recessions is that unemployment rises rapidly but descends very slowly.

While there is a political push both in the United States and Australia to “get back to work”, the experience of past recessions is that unemployment rises rapidly but descends very slowly. A study of Australian recessions since 1974 found that the unemployment rate rose by 1.8 percentage points in each recession year but fell by only 0.5 percentage points in each upswing year.16 That is partly because firms take longer to hire than they do to lay off staff, but also reflects that fact that many leave the workforce and take longer to return.

There is also the build-up of younger people who would otherwise be entering the workforce for the first time but instead confront unemployment. With the COVID-19 crisis hitting many of the occupations typically sought by new labour force entrants, it is likely that youth unemployment will remain elevated.

Governments have been proceeding on the basis that the COVID-19 crisis will be a short, if sharp, recession and have fashioned emergency support for those who have lost their work on that basis. But the disproportionate impact of the crisis on those in the lowest-paid positions suggests the call for government support could be long-lasting.