“Don’t let it be forgot

“That once there was a spot

“For one brief shining moment

“That was known as Camelot”

— Camelot by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe

Caroline Kennedy, daughter of president John F. Kennedy and wife Jacqueline, is being mentioned as under consideration by President Joe Biden to be the next US ambassador to Australia. The name Kennedy still elicits far more than mere passing interest.

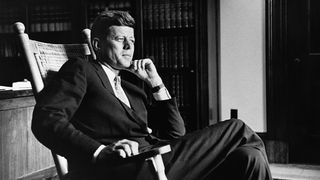

There is an exhibition of photographs at the Australian Catholic University in North Sydney from the John F. Kennedy library in Boston that covers the period of Jack Kennedy’s rise in US politics through the brilliant inauguration in 1961 to the dreadful events in Dallas, Texas, in November 1963. The exhibition has toured Australia previously but is now on permanent display, having been opened by the US consul general in Sydney, Sharon Hudson-Dean. The question that might reasonably be asked is: How is the Kennedy mystique so powerful six decades later? The answer is to be found in the magical word: Camelot.

The question that might reasonably be asked is: How is the Kennedy mystique so powerful six decades later? The answer is to be found in the magical word: Camelot.

Jacqueline Kennedy was determined in December 1963, having just buried her slain husband, to immortalise his administration. To do this, she invited a journalist from Life magazine, Theodore White, to the family compound at Hyannis Port in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, for an interview.

White was well disposed to the Kennedys and went on to become the foremost chronicler of US presidential elections in his series The Making of the President, which had begun in 1960 with JFK’s election.

It was Jackie Kennedy who created the myth of Camelot by telling White of the president’s affection for the musical and quoting the words cited above from the finale. White knew what he had and, while his editors at Life in New York reportedly held the presses at $30,000 an hour, he dictated his seminal work down the phone. Jackie Kennedy listened and when the editors objected to too much reference to Camelot, she shook her head and White insisted on the references remaining. Thus was born the myth of Camelot: drawing on the romance of Arthurian legend, the glamour of the main players and the skills of a court of the best and brightest.

Jack Kennedy was an inspirational figure and his election in November 1960 marked a generational change for the US and more broadly for the West, gripped by the Cold War. With his Brandenburg Gate speech in West Berlin in June 1963, made famous by his declaration “Ich bin ein Berliner”, Kennedy confirmed his unquestioned leadership of the free world.

This was a touchstone of reference to his inaugural speech, crafted by the gifted Theodore Sorensen, when the new president said, “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

Kennedy could make such declarations after his demonstration of courage during the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962. It was a classic case of Soviet overreach, and the lesson might well be learned again by authoritarian aggressors today. Nikita Khrushchev had committed Soviet nuclear weapons to Fidel Castro’s Cuba and Kennedy stared him down, imposing a blockade and forcing a Soviet withdrawal.

Kennedy once remarked of Winston Churchill, (though credit is probably due to Sorensen), that he mobilised the English language and sent it off to war. The young president did precisely the same in both peace and war. The tragedy of barren contemporary politics is that too few leaders endeavour to marshal arguments that inspire hope in the citizenry of democracies for far more elevated futures and far better lives at home and abroad.

The myth of Camelot endures and renews itself regularly as astute politicians quote Kennedy or his brother Robert to this day in the certain knowledge that their words are uplifting. There is far too little of that kind of vision now.

The twitterverse is not the universe, but a handful of words seldom permits more than sniping and catcalling and the denigration of opponents. Few contemporary Western leaders look to employ a major speech to reset an agenda and shift opinion. Too often the language of the emoji replaces the persuasive power of the spoken word embedded in the logic of the real and important.

The myth of Camelot reflects a popular longing for legendary times where public morality mattered and where “the better angels of our nature”, to use Abraham Lincoln’s marvellous phrase, were encouraged and given free rein. Many in the current crop of democratic politicians would do well to set their sights higher.

An essential element of the Camelot myth belongs to the contribution of Jackie Kennedy, bringing the arts into the White House and the American people into the presidential quarters via the medium of television. After the prosperous but staid years of the Eisenhowers and department store furniture, Jackie married US history and creativity to the democratic symbol of American power.

The Kennedy family was not without blemish, especially in the person of Joseph Kennedy Sr. But, as president, Jack Kennedy grew as a leader, demonstrating resolution where needed and political skill as required. It is this leadership capacity that lends power to the Camelot myth, that all was well until tragedy cut it short.

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr wrote the authoritative account of the Kennedy administration in his book A Thousand Days. The critics tend to dismiss Jack Kennedy as a lightweight, comparing him with the landmark achievements of Lyndon Johnson in civil rights and the Great Society when he succeeded to the presidency. But Kennedy laid foundations as reflected in the Peace Corps and the Alliance for Progress. And it was Kennedy who created the concept of the New Frontier and filled it with an American resolve to put astronauts on the moon.

The myth of Camelot endures and renews itself regularly as astute politicians quote Kennedy or his brother Robert to this day in the certain knowledge that their words are uplifting. There is far too little of that kind of vision now. As Bobby Kennedy once observed, some see things as they are and ask: “Why?” RFK dreamed of things that never were and asked: “Why not?”