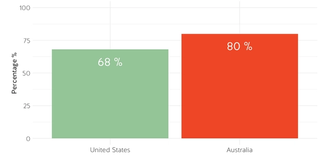

Australians believe “dealing with climate change” is a more important foreign policy goal than Americans, according to recent polling by the United States Studies Centre. In a survey conducted in late January 2021 of 1,186 Americans and 1,183 Australians, 80 per cent of Australian respondents answered “dealing with climate change” was either a “very important” or “fairly important” foreign policy goal, compared to 68 per cent of American respondents. Just seven per cent of Australians said “dealing with global climate change” was “not important at all” compared to more than double that number (16 per cent) of American respondents.

Figure 1: Percentage of American and Australian respondents who answered that climate change was a “very important” or “fairly important” foreign policy goal

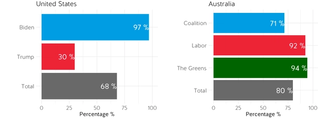

While there were certainly partisan distinctions between Australian voters, American voters appear to be significantly more polarised in their opinions on the importance of dealing with climate change. A nearly unanimous 97 per cent of Biden voters said dealing with global climate change was either a “fairly important” or “very important” foreign policy goal. Less than a third of Trump supporters agreed with the statement and 42 per cent said dealing with climate change globally was “not important at all”. In Australia, 71 per cent of Coalition voters said dealing with climate change was either a “very important” or a “fairly important” foreign policy goal compared to 92 per cent of Labor voters and 94 per cent of Greens voters.

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents by vote who answered that dealing with climate change was a “very important” or “fairly important” foreign policy goal

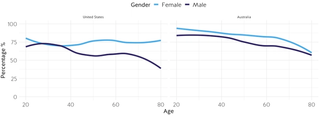

In the United States, females aged between 18 to 29 had the highest levels of agreement that dealing with global climate change was very or fairly important at 77 per cent. Whereas, males above the age of 55 had the lowest agreement at 56 per cent. This trend was similarly reflected in the Australian respondents, where females between the ages of 18 to 29 had the highest response with 91 per cent agreeing that dealing with global climate was either very of fairly important, while males 55 or older had the lowest response at 69 per cent.

Figure 3: Percentage of respondents by age and gender who answered that climate change was a “very important” or “fairly important” foreign policy goal

Peer Pressure: How could US pressure from the Biden administration impact Australia’s attitude towards climate change?

The United States

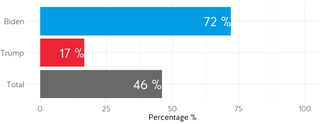

US respondents were asked if the United States should “reward countries who do more to stop climate change with more favourable trade deals and impose costs on those that do not”. Overall, 46 per cent of the US respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the proposition and 20 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed. However, there was a significant partisan split with 72 per cent of Biden voters in favour compared to just 17 per cent of Trump voters.

Older Biden voters, above the ages of 55 were most in favour of rewarding other countries at 77 per cent, compared to 68 per cent of both the 18 to 29 age group and 30 to 54 age group. Of Trump voters, the youngest age group, between 18 to 29, were slightly more in favour at 23 per cent compared to 15 per cent of respondents aged between 30 to 54 and 17 per cent of the over 55 age group.

Figure 4: Percentage of US respondents by vote who agree or strongly agree to the question “Should the United States reward countries who do more to stop climate change with more favourable trade deals, and impose costs on those who do not?”

Australia

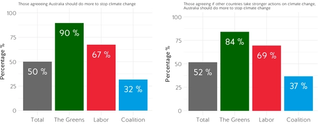

We also assessed Australian attitudes on whether the actions of other countries influenced their view on what Australia should do on climate change. One-half of the Australian respondents were randomly assigned the question, “If other countries take stronger actions on climate change, should Australia do more to stop climate change?” The other half were simply asked, “Should Australia do more to stop climate change?”

Overall, opinions remained consistent between the two groups of Australian respondents as the idea of increased foreign pressure to act on climate change did not significantly change attitudes. Fifty per cent of respondents in the simple condition thought Australia should do more to stop climate change while 52 per cent of respondents answered the same in the condition that introduced foreign pressure. However, this increase was statistically insignificant. In total, from both groups of respondents 51 per cent thought Australia should do more to stop climate change, 38 per cent said the country should continue with current efforts and 11 per cent thought Australia should do less.

Between the two groups, the notion of stronger international action on climate change had a slight impact on Coalition voters, increasing the percentage of Coalition respondents thinking Australia should do more to 37 per cent from 32 per cent.

As shown in Figure 1, while 80 per cent of Australians said, “dealing with climate change” was a “fairly important” or “very important” foreign policy goal, it is striking that only 50 per cent of the same respondents thought Australia “should do more to stop climate change”. These results suggest that climate change as a foreign policy goal issue is more popular with the public than domestic climate change policy.

Figure 5: Percentage of respondents by vote who thought Australia should do more to stop climate change. Half of respondents were asked “If other countries take stronger actions on climate change, should Australia do more?” The other half or respondents were asked “Should Australia do more to stop climate change?”

The idea of other countries doing more to stop climate change also had some influence on respondents from different states. When the notion of external pressure was given, 55 per cent of Queensland respondents said Australia should do more, compared to 45 per cent without it. Similarly, Western Australian respondents increased to 46 per cent from 37 per cent. This effect was also seen when examining where respondents lived. Foreign pressure on Australia to stop climate change pushed 55 per cent of people from capital cities to say Australia should do more, compared to 49 per cent responding that Australia should do more irrespective of other countries. In regional and rural areas of Australia however, the idea of foreign pressure led to a decrease in support for greater climate action, slipping down to 45 per cent, from 52 per cent originally.

Table 1: Australian attitudes on climate change by location

|

Location |

Percentage agreeing “Australia should do more to stop climate change” |

Percentage agreeing “If other countries take stronger actions on climate change, Australia should do more to stop climate change” |

Difference when “If other countries take stronger actions on climate change” is added |

|

New South Wales |

51.8 |

52.3 |

+0.5 |

|

Victoria |

49.6 |

49.9 |

+0.3 |

|

Queensland |

45.0 |

54.9 |

+9.9 |

|

Western Australia |

36.8 |

46.1 |

+9.3 |

|

Capital cities |

48.8 |

54.8 |

+6.0 |

|

Regional/rural |

51.6 |

45.0 |

-6.6 |

Amid increasing pressure by the Biden administration for other countries to do more to mitigate climate change, these results suggest that US pressure on Australia in this area may not lead to changed opinions in Australia.

It also suggests that while the rhetoric on climate change differs quite significantly between current Australian and US political leaders, the general public opinion on climate change is more closely aligned between the two countries. The majority of Australians, just like the majority of Americans, think that climate change is an important global issue. This majority is consistent between males and females and across the different age groups.

There is, however, a notable distinction between the two countries as to how the issue of climate change has been politicised. While it has led to a significant partisan division in the United States between Trump and Biden voters, in Australia there is generally a unanimous agreement between Coalition, Labor and Greens voters that climate change is an important issue.

Australian political division becomes apparent when considering how much action Australia should be taking to combat climate change. Most Labor and Greens voters think Australia should be doing more against climate change, but this is not the case for Coalition voters.

Ultimately, Australian politicians and the public may disagree on how much Australia should be doing on climate change, but the United States faces an even greater challenge — reaching a bipartisan agreement that climate change is an important issue to at all.

.jpg?rect=0,80,3000,1989&fp-x=0.5&fp-y=0.44772296905517583&w=320&h=212&fit=crop&crop=focalpoint&auto=format)