In the lead up to the US midterm elections, political campaigns across the nation focus their efforts on ensuring supporters show up at the ballot box on November 6.

In the United States where voting is not compulsory, unlike Australia, campaigns are tasked with registering and mobilising eligible voters. This is a considerable undertaking. Millions of dollars are spent on voter mobilisation (informally known as ‘get out the vote’ or GOTV) every election cycle.

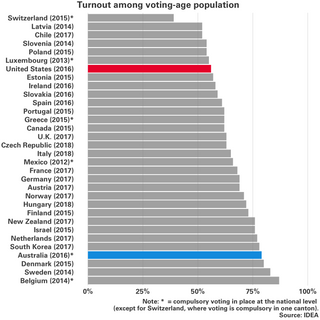

GOTV efforts are necessary strategies for campaigns, as voter turnout in the United States is low.

Campaigns use various means to mobilise supporters, including direct mail, digital marketing and phone calls. However, the priority of any GOTV strategy is still door-to-door canvassing.

In-person voter mobilisation

There’s plenty of research to suggest that the effects of door-to-door canvassing are small, but nonetheless impactful. In a large-scale experiment of the American electorate during the 1998 midterms, researchers found that turnout of those in a treatment group who received in-person contact through door-to-door canvassing regarding the election was 6.3 per cent higher than those who were not contacted at all.

During the midterms – where turnout is usually significantly lower than presidential election years – this increase takes on additional significance, and the number of additional voters could certainly act as a decisive factor in determining an election result. Consider that in 2016 Donald Trump won Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin by 0.2, 0.7 and 0.8 percentage points, respectively (or 10,704, 46,765 and 22,177 votes). If Hillary Clinton had done one point better in each state, she'd have won the electoral vote, too.

Since the Obama campaigns of 2008 and 2012, Democrats and Republicans have increasingly streamlined this practice using digital organising tools and advanced data analytics. In the 2018 midterms, campaigns of both parties have equipped volunteers with mobile canvassing apps, which provide template scripts, identify houses to target and log data on voter interactions.

Yet, even as such technology has reached unprecedented levels of usage, in-person canvassing remains time-consuming and not particularly efficient. This is especially true relative to the myriad of opportunities to contact and influence millions of would-be voters online.

Text messaging voter mobilisation

The ‘breakout tech’ of 2018 GOTV efforts – at least according to one Republican digital strategist – is text messaging.

Even though text messaging has been used by campaigns since Obama 2008, these midterms have seen Republican and Democratic campaigns making more substantial use of ‘peer-to-peer’ texting apps.

First deployed at a large scale by the Bernie Sanders 2016 campaign, these allow canvassers to manually send an immense daily volume of personalised messages and maintain thousands of ongoing conversations, whilst skirting federal restrictions on automated mass texting.

Republican and Democratic campaigns are making more substantial use of ‘peer-to-peer’ texting apps.

Anecdotal evidence from the Sanders campaign (and others since) suggests that this particular form of text canvassing can be an effective mobiliser, and – especially for younger voters – has a far greater cut-through rate than phonecalls or email. More generally, several studies of past US elections have shown that text messaging, particularly when personalised, can increase a recipient’s likelihood of voting by as much as 3 per cent.

In the age of social media, it may seem surprising that text messaging is the standout GOTV method of the 2018 midterms. But social media is still used extensively by campaigns.

Digital and social media voter mobilisation

Campaigns and affiliated political action committees are on track to spend almost US$2 billion on digital advertising this election cycle (about 22 per cent of total political advertising), on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Google. This is up from less than 1 per cent of overall spending in 2014.

However, whilst campaign activity on social media undoubtedly aims to encourage supporter turnout, it can be difficult to differentiate specific GOTV tactics from more general political advertising.

Regardless, most major social media networks are directly participating in GOTV activity. On National Voter Registration Day (25 September), Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, Google, Reddit and even Tinder all provided users with prompts encouraging them to register, and with links to voting information. They will do so again on election day.

Explainer: Women candidates in the midterm elections

The effectiveness of such GOTV prompts is varied. In an experimental study on Facebook conducted during the 2010 midterms for 61 million Americans, researchers found that those who received notification regarding election day did not turnout at higher rates than those who did not. However, a second treatment group not only received the informational message, but could also see which friends clicked an “I Voted” button on election day. Researchers found those in the second group were 0.39 per cent more likely to vote than those who received the information-only message. This finding supports research showing that mobilisation is particularly strong when voters are influenced and even encouraged by close peers.

Although online canvassing reduces the personalisation of voter contact relative to door-to-door canvassing, such research suggests that some forms of GOTV efforts via social media could nevertheless have a significant effect on turnout – after all, even 0.39 per cent of a 61 million-strong sample is a lot of votes.

Who is using social media?

An interesting dynamic to consider is the age of these platforms’ users. According to the Pew Research Center, Facebook is used by 68 per cent of US adults. Instagram and Snapchat have far lower adult usage rates – respectively, 35 per cent and 27 per cent.

Facebook is used by 81 per cent of Americans aged 18-29, but usage is also substantial across older age groups – 65 per cent of 50-64 year olds use the platform, as do 41 per cent of people 65 and older.

Facebook is used by 81 per cent of Americans aged 18-29, but usage is also substantial across older age groups.

Use of Instagram and Snapchat is concentrated far more heavily amongst younger people. Although both are used by around two thirds of 18-29 year olds, their usage rate nosedives amongst older generations – just over a fifth of 50-64 year olds use Instagram, and only 10 per cent use Snapchat.

This suggests that the audience for social media GOTV efforts is predominantly young people, a demographic that overwhelmingly favours Democrats.

The youth vote

Young voters are notoriously poor at turning out on election day – in the 2014 midterms, just 21 per cent of 18-29 year olds voted. However, there are signs that they could be unusually engaged this election cycle. Young voter turnout was strong and seemingly consequential in several high-profile special elections in 2017, and a Harvard Institute of Politics poll conducted earlier this year found that 37 per cent of Americans under 30 report they will ‘definitely be voting’ these midterms (compared to 23 per cent in 2014).

Although the share that actually vote will not be this high, it seems plausible that certain social media GOTV efforts could build on this enthusiasm, and lend a tiny boost to youth turnout in these midterms – the kind of boost that can sometimes decide elections.