After two years of negotiation, Congress passed the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 which was signed into law by President Biden on 9 August 2022. The act authorises US$280 billion (AU$410.6 billion) funding to shore up semiconductors, perhaps the United States’ greatest vulnerability when it comes to securing supply chains, and to drive the US-led invention of frontier technologies ahead of its global competitors.

The CHIPS and Science Act contains the largest investment in US research and development (R&D) — a key building block of innovation — in US history.

The legislation’s historic federal investments represent a seismic shift in the US approach to the funding and composition of its innovation, technology, and manufacturing sector. The act contains the largest investment in US research and development (R&D) — a key building block of innovation — in US history. It is also one of the largest single investments in US manufacturing in decades, allocating over 100 times more public investment into the nation’s chip industry than the major government investment in semiconductors, the SEMATECH initiative founded in 1987, when the United States faced semiconductor market competition with Japan.

Commanding bipartisan support for such a sizeable bill in the House (243-187) and the Senate (64-33), even amid record levels of inflation, the CHIPS and Science Act represents a decisive departure from the market-led economic thinking that dominated US policymaking since the 1980s, and a clear embrace of a strategic, government-led economic intervention — an industrial policy — in the US advanced technologies sector.

This brief examines the contents of the legislation as well as its strategic intent and implications for Australia.

What is the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022?

The CHIPS and Science Act can be understood in two parts: the semiconductors-focused CHIPS component and the technological R&D-focused Science component.

Division A: The CHIPS Act

The Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America Act is the main anchor of the CHIPS and Science Act. It authorises over US$52 billion worth of government incentives to increase the US domestic supply of computer chips and the construction of semiconductor fabrication facilities within the United States. Among these incentives is the CHIPS for America Fund, which includes funding enabling the Department of Commerce to provide up to US$39 billion in government loans and other financial assistance - including a 25 per cent tax credit.

"Semiconductors are an essential building block in the goods and products that Americans use everyday. These computer chips are critical to a range of sectors and products from cars to smartphones to medical equipment and even vacuum cleaners. They help power our infrastructure from our grid to our broadband."

FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Brining Semiconductor Manufacturing Back to America (21 January 2022)

Several domestic and international companies have already announced their intentions to utilise the schemes and build fabrication facilities within the United States. Shortly after the House passed the CHIPS and Science Act on 28 July 2022, Intel CEO Pat Geisinger, for example, announced that the firm would proceed with its promise to invest US$20 billion into the building of two cutting-edge fabrication facilities in Ohio. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) also announced a plan to build a US$12 billion facility in Arizona. Additionally, South Korea’s Samsung pledged to construct a US$17 billion factory in Texas. TSMC and Samsung together represent two-thirds of the global semiconductor market share, with TSMC alone providing 92 per cent of the world’s supply of advanced chips.

The act’s investment in US advanced manufacturing capabilities received bipartisan support because of its associated economic benefit to the country’s regional economies and workforces, both of which have faced competition from offshore manufacturers and changes to domestic industry. The Semiconductor Industry Association, the US leading semiconductor industry group, estimates government investments within the CHIPS Act would, over a five-year period, ultimately add US$24.6 billion to the US economy and create 185,000 jobs.

Why does America need to make semiconductors?

For US policymakers, the CHIPS Act not only represents an economic opportunity, but a critical national security priority. While US-headquartered firms dominate among the world’s semiconductor designers, long-term underinvestment in advanced manufacturing and the movement of private companies to offshore facilities have ultimately hindered the United States’ ability to manufacture semiconductors domestically.

American-made chips in 2020 only accounted for 12 per cent of the world’s manufacturing of chips, down from 37 per cent in 1990; while in the same period, the share of Chinese-made chips went from a negligible amount to 15 per cent.

The United States has resultingly found itself increasingly reliant on sensitive foreign supply chains for its extensive microchip needs. American-made chips in 2020 only accounted for 12 per cent of the world’s manufacturing of chips, down from 37 per cent in 1990; while in the same period, the share of Chinese-made chips went from a negligible amount to 15 per cent. The TSMC fabrication facility based in Taipei, provides 92 per cent of the world’s supply of advanced chips (chips less than 10 nanometres wide), including about 90 per cent of the chips used in the products of leading US tech firms Apple, Amazon and Google, and 90 per cent of the chips used by the US military. As tensions ramp up between the United States and China, and China undertakes its own industrial-scale effort to further increase its domestic production of semiconductors, the United States’ diminished advanced manufacturing capability, and dependence on geopolitically sensitive suppliers, poses an immediate risk — particularly considering that the US military alone requires a yearly supply of approximately 1.9 billion chips to maintain its defences. As Department of Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said before the passing of the CHIPS and Science Act in July 2022, “... if, God forbid, China were to — in any way — disrupt our ability to buy these chips from Taiwan, it would really be an absolute crisis in our ability to protect ourselves.”

Beyond creating incentives to enhance domestic manufacturing, the CHIPS Act also seeks to improve the nation’s long-term competitiveness and innovative edge by promoting the development of technical expertise and STEM workforce training. It is estimated that around 40 per cent of workers at US semiconductor manufacturers were born overseas as the United States faces several challenges to its home-grown STEM workforce. To remedy this, the act launched a US$200 million workforce and education fund, to be delivered through the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Table 1. The CHIPS Act

|

Program under the CHIPS Act |

Funding over five years |

What will the money do? |

Who will implement or oversee it? |

|

CHIPS for America Fund |

US$50 billion |

Provides loans for chip production crucial to US national and economic security interests and critical industries, as well as the creation of workforce development programs. The funding is split into two channels

|

Department of Commerce |

|

CHIPS for America Defense Fund |

US$2 billion |

Establishes a network of onshore, university-based research centres focused on the commercialisation of defence-related semiconductor technologies and workforce training |

Department of Defense |

|

CHIPS for America International Technology Security and Innovation |

US$500 million |

A fund for the Department of State, and several related agencies, to support the coordination of information and communication on the status of technology security and international supply chains |

Department of State — US Agency for International Development, the Export-Import Bank, and the US International Development Finance Corporation |

|

CHIPS for America Workforce and Education Fund |

US$200 million |

Funds provided to promote the growth of the semiconductor workforce, projected to need an additional 90,000 workers by 2025 |

National Science Foundation |

Division B: The Research and Development, Competition and Innovation Act

The second component of the CHIPS and Science Act designates funding for R&D in critical and emerging technologies. This federal investment is the largest investment in public R&D and STEM education in US history, setting ambitious targets for the top-line budgets of several government agencies including the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

It further allocates US$20 billion for the creation of a new NSF Directorate for Technology Innovation and Partnerships (TIP), which will assume responsibility for several existing NSF programs that accelerate the commercialisation of new technologies in artificial intelligence, robotics, materials science and manufacturing, quantum computing, and telecommunications among others. TIP will also spearhead the research of technological solutions to social, national and geostrategic challenges.

Alongside sponsoring research and research commercialisation, the funding within these organisations is designed to build new regional technological hubs necessary to boost local US economies and re-shore supply chains. Among some of the most celebrated initiatives include a US$2.3 billion boost to the Department of Commerce’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership Program, which coordinates public-private partnerships with small and medium-sized manufacturers across the country, and the US$11 billion directive to build 20 regional technology hubs to support regional areas experiencing persistent economic distress.

Table 2. The Research and Development, Competition and Innovation Act

|

Government organisation receiving funds from the CHIPS & Science Act |

What does the organisation do? |

Significant programs funded by the CHIPS and Science Act |

Five-year authorisation in the CHIPS and Science Act |

|

The National Science Foundation’s mission includes support for all fields of fundamental science and engineering, except for medical sciences. They are tasked with keeping the United States at the leading edge of discovery. |

|

US$81 billion |

|

|

The Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) |

The NIST promotes US innovation and industrial competitiveness by advancing science, standards and technology in ways that enhance economic security and improve quality of life. |

|

US$10 billion |

|

The Department of Energy’s Office of Science |

The Office of Science accounts for more than half the Department of Energy’s R&D budget and is the US largest financer of research in the physical sciences. |

The Science Act component reauthorises funding for Department of Energy research and development programs set to improve federal investments in clean energy innovation and technology commercialisation. Among other initiatives, this includes:

|

US$50 billion |

American innovation under threat and the competition for the 21st century

While the United States maintains a long-standing reputation for its inventiveness, the bipartisan support for the act is in no small part driven by the fact that the United States is no longer the dominant innovative power that it once was. The act’s provisions for scientific research and development are, therefore, broadly considered a national and economic security imperative. As President Biden said in a statement endorsing unprecedented investments in domestic R&D and semiconductor manufacturing,

“We are in a competition to win the 21st century, and the starting gun has gone off. As other countries continue to invest in their own research and development, we cannot risk falling behind. America must maintain its position as the most innovative and productive nation on Earth.”

For most of the last half-century, the United States led the world’s research and development of commercial and military technologies. In the 1960s, the United States accounted for over two-thirds (69 per cent) of global R&D spending. The US government played a crucial role in financing the technological inventions required for new defence technologies, military advancement, and preparedness. Through its Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the United States developed several key innovations and technological breakthroughs that are foundational to the last half century of modern life, including computer chips, weather satellites, drones, global positioning systems, touch screens and the internet itself.

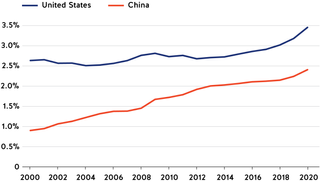

However, by 2019, the US share of the world’s R&D funding had fallen to about 30 per cent, with the global R&D scene now dotted with foreign competitors. For example, in the past 20 years alone, China’s share of global R&D spending has climbed from 4.9 per cent in 2000 to 23.9 per cent by 2019. At the same time, the US composition of R&D funding changed dramatically as business investments surged from the 1970s onward, while government spending decreased significantly. American businesses now play an outsized role in the composition of US R&D spending, accounting for 70.7 per cent of total US R&D spending in 2019.

Figure 1. Gross domestic spending on R&D as a proportion of total GDP, 2000-2020

When it comes to competition with China, the US private sector and its business-friendly deregulation policies, flexibility and agility are often considered America’s asymmetrical strength. Yet, in seeking efficiencies to protect their bottom line, major technology corporations are also more likely to pursue R&D in sectors and countries where profits are more likely, and are therefore potentially more willing to cooperate with countries where the dual-use implications of some R&D efforts may be counter to US security interests.

In the context of rapid technological advancement, even US businesses’ innate orientation towards innovation and reshoring US firms’ production may not be enough to keep the United States prosperous and secure, or ahead of key strategic rivals like China. The CHIPS and Science Act responds to such concerns by making the receipt of the federal subsidies contingent on companies’ restriction of their chipmaking activity and business investments in China and other countries of concern. For manufacturers like Intel and TSMC, who have substantial business in China, this means they will be unable to increase their production of chips in China, or upgrade or expand their facilities there for at least 10 years and will be forced to choose between growth opportunities in either China or the United States.

“Science and technology innovation has become a critical support for increasing comprehensive national strength… whoever holds the key to science and technology innovation makes an offensive move in the chess game and will be able to pre-empt the rivals and win the advantages.”

President Xi Jinping (2014)

Both the Biden administration and former Trump administration officials are explicit that the shifted sentiment around industrial policy is unique to the context of China’s rise and increasing competition with the United States. Indeed, the two-thirds bipartisan consensus around the Senate’s 2021 United States Innovation and Competition Act (68-32) made this clear, as the sprawling 2,400-page precursor to the CHIPS and Science Act took on the nickname of ‘the anti-China’ bill.

Supercharged by the Chinese Communist Party’s industrial-scale investment in its Made in China 2025 policy, China’s R&D spending has increased at an average of 18 per cent each year since 2000. The scale and speed of several Chinese technological breakthroughs, including the invention and rollout of Chinese fifth-generation telecommunication networks (5G) and developments in artificial intelligence, raised concerns in Washington that China has already become a leading power in several of the critical and emerging technologies of the future.

What are the implications and opportunities for Australia?

Industrial policies are often criticised as protectionist and unable to leverage the many advantages associated with trade and multilateral engagement. As such, some Australians may be concerned that the American embrace of industry policy will complicate the US-Australian working relationship. Indeed, the Trump administration’s own America First-inspired economic policies in response to increased competition with China were often seen as alienating to vital partners across Europe and the Indo-Pacific, and to worsen economic outcomes in Australia.

The United States’ competitive advantages in its technology sector will not only come from its ability to self-produce critical goods like semiconductors, but more importantly from its network of allies. Acknowledging this, the Biden administration has made many promising and welcomed signals of re-engaging with its allies in the Indo-Pacific and working together on shared challenges, like trade coercion and supply chain disruptions. While China’s stature as the dominant trading partner for the Indo-Pacific region and its seven-year-old Made in China 2025 strategy lends it some advantages in the race to innovate, this advantage loses its significance when the United States partners with like-minded allies and partners to: leverage consumer markets preferencing American-made products; bypass supply chain insecurities; and share talent in the co-development of critical and emerging technologies. Several nations’ refusal to allow Huawei into their telecommunication networks is a pertinent example of this in action.

As the United States looks to enhance its advanced manufacturing abilities and research and commercialisation of emerging technologies, Australia can leverage these existing groupings and established trust with the United States to advocate for its own interests.

Both the United States and Australia stand to benefit from closer cooperation on matters concerning technological competitiveness and security. Already both nations have demonstrated their willingness to work together on defence-related technological research and development through arrangements such as the AUKUS agreement and several Quad initiatives. As the United States looks to enhance its advanced manufacturing abilities and research and commercialisation of emerging technologies, Australia can leverage these existing groupings and established trust with the United States to advocate for its own interests. There is no shortage of ideas about where the United States and Australia can collaborate in the emerging technology field. Some notable ones include:

- Establish an international technology alliance with trusted, technically adept partners to accelerate technological developments in key strategic competencies. This would involve nations working on areas of comparative advantage, sharing developments and resources, ensuring the interoperability of digital infrastructure and harmonising guidelines for the use of emerging technologies.

- Share human capital and technical expertise with the United States as both nations grapple with worker shortages and competing demand. Establish a talent exchange program for technical experts to visit US national laboratories and technological hubs in coordination with Australian research programs, as well as create shared educational programs to ensure the next generation of STEM workers.

- Quickly resolve intellectual property rights concerns and align export controls for more effective research commercialisation, and to create market-based incentives for shared innovation across countries.

- Share information, threat monitoring, risk assessments and strategies regarding cyber threats, supply chain disruptions and security breaches.

- Codify shared values and principles surrounding the future use of emerging technologies, especially on matters concerning data security, privacy and surveillance, and petition to have these standardised at an international level, including the prosecution of distortive trade behaviours and intellectual property thefts.

With the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act as well as other legislation on infrastructure and climate change, President Biden fulfills a key campaign pledge to invest in America. Now he must consider when and how he will leverage these domestic investments into deeper and more effective engagement overseas, and give credit to his declaration that “America is back”