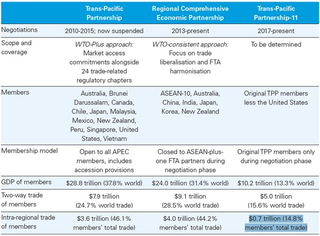

A rising anti-globalist current in the United States has fundamentally changed the trade agenda in the Asia-Pacific. Since 2010, competition has been building between two emerging mega-regional trade agreements with different visions about how to multilateralise Asian free trade agreements (FTAs). The ASEAN-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was narrowly focused on lowering tariffs among six existing ‘ASEAN-plus-one’ FTAs. By contrast, the US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) provided a more ambitious approach to regional trade based on regulatory rule-making for investment, services, and the digital economy. The 12-member TPP appeared to have the upper hand in 2015 when negotiators settled on a deal. But following a populist backlash against the TPP in America — that eventually led Donald Trump to withdraw from the deal — the TPP cannot enter into force in its existing form. For the first time since 1989 the United States is absent from key negotiations over the future shape of economic regionalism in Asia.

The collapse of the TPP has reignited the contest over the future shape of Asia’s trade architecture. China and ASEAN responded by immediately positioning RCEP as an alternative, increasing the pace of negotiations over 2017. At the same time, several TPP members — led by Australia and Japan — have begun to advocate for a reformulated TPP-11 which would retain some of the features of its predecessor without the United States. As their respective negotiations move towards completion, RCEP and TPP-11 are vying to become the template for a new multilateral trade architecture in Asia.

Although the protectionist trade policy instincts of the Trump administration make US involvement unlikely in the immediate term, there is a strong economic case for Washington to remain a key part of a regional trade system. America’s economic integration with the region runs deep. Members of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) accounted for 66 per cent of US two-way trade in 2016, while the United States comprises 18 per cent of APEC’s two-way trade.1 If the new Asia-Pacific architecture is configured around the principle of ‘open regionalism’, a space could be carved out for Washington to re-engage in future years. For now, RCEP and TPP-11 renegotiations offer Australia and like-minded partners in the region an opportunity to adopt institutional mechanisms which ‘future proof’ these agreements for America’s eventual return.

Competing designs: The TPP and RCEP models for Asian trade

Multilateralism has been the defining feature of recent trade policy initiatives in the Asia-Pacific. Since the early 2000s, bilateral FTAs have proliferated in the region, with 54 agreements negotiated between APEC members by 2016.2 This created the so-called ‘noodle bowl’ problem:3 rather than having a single, transparent, and integrated set of rules, Asia’s regional trade system has become fragmented into a number of inconsistent bilateral arrangements. Cognisant of this problem, governments began exploring strategies to multilateralise regional trade architecture through the negotiation of large, multi-member trade agreements. Two such agreements were proposed — the TPP and RCEP — offering different visions for how trade multilateralism in Asia should be achieved.

While the promise of greater access to the large US market attracted some developing economies, such as Vietnam and Mexico; others, most notably China and Indonesia, declined invitations to join the TPP negotiations.

The TPP promised a ‘high ambition’ trade agreement amongst a group of like-minded governments. It focused on the so-called ‘WTO-Plus’ issues — rules for investment, services, environment, digital economy, and intellectual property — which have yet to be substantively addressed by World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements. These are favoured by developed and service sector-oriented economies as they provide regulatory rules for the increasingly important service and technology sectors. However, they also impose high reform costs by requiring extensive changes to domestic policy regimes. These reform costs can be prohibitive for countries at earlier stages of development. While the promise of greater access to the large US market attracted some developing economies (such as Vietnam and Mexico), others (most notably China and Indonesia) declined invitations to join the TPP negotiations.

In contrast, RCEP offered ‘lower ambition’ liberalisation with an Asia-focused membership structure. Designed as an ASEAN-centred agreement, its principal objective was to multilateralise the six pre-existing ASEAN-plus-one FTAs4 into a single regional agreement. The focus of negotiations has been a more conventional emphasis on mutual tariff reductions, with the aim only to be ‘WTO-consistent’ rather than ‘WTO-Plus’. RCEP’s members have adopted a consensus-driven approach to negotiations, which has seen more contentious elements excluded from the agreement. As RCEP is calibrated to the interests of developing economies like India, China, and ASEAN nations, it offered a template in which all Asian governments were willing to participate. But it did so by offering far less in terms of regulatory reform, and by excluding the United States, Asia’s most important extra-regional trade partner.

When TPP negotiations finished ahead of RCEP in October 2015, many concluded it would become the new model for the Asia-Pacific trade system. However, these expectations were soon challenged by the election of Donald Trump. Trump had campaigned extensively against free trade in general — and the TPP in particular — during the 2016 presidential race,5 and withdrew the United States from the agreement in his first executive order in January 2017.6 For the TPP to enter into force, at least six members (accounting for 85 per cent of the bloc’s GDP) must ratify the agreement.7 As the United States alone accounts for 60 per cent of the TPP’s economic size, its withdrawal made it numerically impossible for the agreement to continue as originally configured.

The Chinese government immediately seized on the opportunity of a failed TPP to back a renewed push for RCEP, using the APEC Summit in November 2016 to call for a speedy completion of the deal.8 The pace of negotiations has intensified over 2017; currently targeting a completion in early 2018.9 At the same time, however, the eleven remaining TPP members have begun exploring options to reconstitute the agreement without America. Led by Australia10 and Japan,11 these efforts delivered an agreement to assess the prospects for a substitute TPP-11 in May 2017.12 Five TPP-11 negotiations have been convened so far, and are due to report outcomes before the APEC Summit beginning on 8 November this year.13

The TPP-11 initiative: Purity or pragmatism?

The core objective of the TPP-11 is to salvage something from the original agreement in the face of US withdrawal. The ongoing commitment of Japan and Australia reflects the perceived value of the TPP as a free trade agreement that is also a rule-making instrument, which establishes high-standard regulatory rules in areas such as investment, services, environment, intellectual property, and the digital economy. Salvaging these regulatory elements could, in principle, be a relatively straightforward process. If the 85 per cent GDP rule is relaxed the remaining eleven members could put the original agreement into effect without the United States.

Importantly, a TPP-11 agreement would provide a clear pathway for the United States to rejoin the Asian trade system in the future. Its membership model was premised on the principle of ‘open regionalism’: that regional economic agreements should be open to all Asia-Pacific countries. The TPP’s original negotiations were open to all APEC members; and the agreed text included an “accession mechanism” whereby new members could apply to join.14 This accession mechanism would have enabled any APEC economy — such as South Korea, Indonesia, China, or the United States — to seek membership of the TPP in the future.

This accession mechanism enables any APEC economy – such as South Korea, Indonesia, China, or the United States – to seek membership of the TPP in the future.

Australia has identified US accession as a critical objective, with Trade Minister Steve Ciobo arguing, “it’s important to leave the door open to the United States”.15 While the Trump administration has unequivocally stated it has no intentions of doing so,16 it should be noted that in the post-1945 era, all US presidents from both major parties have actively engaged in trade agreement-making. A future US administration with different trade policy preferences may see economic and/or strategic value in re-joining the TPP.

In the meantime, the TPP-11 parties need to agree on the extent to which the original agreement is revised. Here, a split between developed and developing economy members will prove difficult to navigate. For the developed economies, the key value of the TPP-11 lies in preserving its WTO-Plus regulatory provisions. They therefore favour a minimalist approach to renegotiation that will make as few variations as is politically viable.17 Kazuyoshi Umemoto, Japan’s chief negotiator, has stressed the importance of “[carrying] on working without lowering the TPP’s high standards”.18

A minimalist renegotiation that is still agreeable to the developing country members would be difficult to achieve. At the heart of the original TPP was a political-economic trade-off under which developed economies obtained their desired regulatory commitments, and developing economies gained preferential access to large markets. But with almost two-thirds of these market access gains now gone, developing economies are unlikely to accept the high domestic reforms costs of the original regulatory provisions.

There are also questions over whether provisions initially included to secure support from the US Congress — particularly the labour standards chapter and intellectual property protections for biologic drugs19 — should be retained without receiving access to the US market in return. Vietnam and Malaysia have reportedly expressed significant reservations about a TPP-11 that fails to compensate for the absence of the United States.20

Retaining as many of the original provisions as possible will increase the probability of a future US administration re-joining the TPP

Some degree of renegotiation will be essential if the TPP-11 initiative is to succeed. The outcome of such negotiations will determine not only the viability of a TPP-11, but also the likelihood of future US accession. If the required changes are extensive and remove or dilute many of the original US-requested inclusions, a more positively-disposed US administration may instead struggle to secure congressional support. One management option is the use of a ‘snapback’ approach, currently being considered by negotiators, under which a revised agreement would revert to the original text upon re-entry of the United States. But the likelihood that this will be appealing to all members, given the uncertainty surrounding the future outlook of US trade policy, remains to be seen. Nonetheless, retaining as many of the original provisions as possible will increase the probability of a future US administration re-joining the TPP.

RCEP: An ‘open’ Asian trade architecture?

Since the US withdrawal from TPP, the prospect that RCEP will become the new model for Asia’s regional trade architecture has grown significantly. Its lower ambition is both a vice and virtue: while it will offer less in the way of liberalisation, fewer domestic reform costs also lower the bar for developing economy participation.21 Political momentum has rounded behind RCEP, with the negotiating parties claiming it will serve as a “beacon of open regionalism”22 in the face of rising protectionist moves around the world. Perhaps most importantly, with the TPP now a fraction of its original size, RCEP is the only genuinely regional trade agreement in Asia.

In comparison to the TPP, RCEP is a sub-optimal but still valuable trade strategy for developed economies like Australia. Its low ambition approach means it will not offer the regulatory rule-making preferred by service-based economies. Nor does it include the United States, Australia’s number two trade partner and leading source of foreign investment. But RCEP still offers several benefits to Australia, including:

- Market access gains, particularly in the agricultural and services sectors23

- Country-specific commitments on foreign investment, which will help broaden investment relationships to new Asian partners24

- The first multilateral framework for the Asian trade system, enabling easier participation in regional value chains25

- Australia’s first preferential trade agreement to include India, an emerging economic partner.26

A key unresolved issue is whether RCEP will embody the principle of open regionalism in its future membership. During the negotiation phase, RCEP has been open only to the 16 ASEAN-plus-one economies. But members have made an in-principle agreement to include an accession clause that enables additional parties to join post-completion.27 The design of this mechanism will have a longstanding effect on the architecture of the regional trade system. If RCEP includes a similar accession mechanism to the TPP — which invites and encourages the participation from all APEC members — it will offer a genuinely ‘Asia-Pacific’ membership model. It would also open the door to future US accession, a move which would significantly increase the size and global reach of the agreement.28

For countries with more ambitious trade policy preferences, a robust consultation mechanism would provide a way to upgrade RCEP’s regulatory standards once the initial negotiations are complete.

Another challenging issue is whether the RCEP agreement will be able to expand the scope of its regulatory coverage. The TPP was designed as a ‘living agreement’ and included a consultative TPP Commission, the purpose of which was to review and consider amendments to the original text.29 This mechanism allows further provisions to be added by consensus amongst the members. While RCEP will likely include a consultation mechanism, its constitution and remit remain to be determined. If a similar mechanism to that in the TPP is included, RCEP’s longer-term value may not lie in what is agreed now but instead its role as a framework for negotiating future liberalisation commitments. For countries with more ambitious trade policy preferences, a robust consultation mechanism would provide a way to upgrade RCEP’s regulatory standards once the initial negotiations are complete.

These membership and scope issues are interlinked. RCEP’s modest reform ambitions reflect its orientation towards predominantly developing economy members. However, an open accession mechanism could present dynamic opportunities to scale-up membership and content. If the United States was to join in future years, it would not only significantly increase RCEP’s size, but also add a powerful advocate for liberalisation to the membership. This would create a ‘WTO-Plus coalition’ within RCEP — comprising Australia, Japan, Korea, Singapore and the United States — which would be much better positioned to push for regulatory rule-making as the agreement evolves. Securing open accession and consultation mechanisms will be essential to ‘future proofing’ RCEP.

Maintaining US engagement in the Asia-Pacific trade system

For the first time in more than two decades, the United States is absent from the trade negotiation table in Asia, and facing exclusion from the largest and most dynamic region of the world economy at the precise time that regional trade architecture is being redesigned.

This would create a ‘WTO-Plus coalition’ within RCEP – comprising Australia, Japan, Korea, Singapore and the United States – which would be much better positioned to push for regulatory rule-making as the agreement evolves.

Reinserting the United States will prove difficult. Trump has ruled out participation in either TPP-11 or RCEP negotiations, leaving the task to a future administration. By this time, regional architecture will have changed dramatically. Success for the TPP-11 would provide the easier pathway for US involvement, but the need for complex renegotiation makes its current prospects uncertain. RCEP is the likelier of the two agreements at this point, but members have yet to decide upon the design of its important accession and consultation mechanisms.

As TPP-11 and RCEP continue to advance, Australian negotiators face the challenging task of balancing national trade interests against the compromises required by partners. Australia should adopt a forward-looking position which seeks regional arrangements that are as open as possible, both for the United States and all other Asian countries. Specifically, it should work to:

- Ensure a regional trade architecture that can accommodate future US involvement. The United States is Australia’s number two trade partner, leading foreign investor, and a key ally in driving WTO-Plus reforms. Maintaining US engagement in the regional trade system is therefore a high priority. While there is uncertainty over the future direction of US trade policy, both RCEP and the TPP-11 can be designed in ways that maximise the likelihood of future US involvement.

- Maintain a high-standard TPP agreement. The central rationale for the TPP-11 is to preserve the advanced regulatory rule-making of the original TPP agreement. A significantly diluted deal would undermine its raison d’être, and threaten the prospects for future US accession. Australia should work with like-minded countries to preserve the WTO-Plus components, and be willing to suspend but not abandon negotiations if a high-standard outcome cannot be obtained.

- Secure an open RCEP agreement. In contrast to the TPP, RCEP primarily offers market access gains and the benefits that flow from establishing an inclusive, region-wide multilateral agreement. To secure these gains, compromise over regulatory provisions will be required in initial stages. Australia should advocate for an open accession mechanism which enables new members — including but not limited to the United States — to join. It should also push for a strong consultative mechanism that will enable future upgrades to its regulatory provisions.