Though it hasn’t made the headlines, Labor’s first complete budget in nearly 10 years includes “Australia’s plan to become a renewable energy superpower.” It’s striking language pulled straight from the pages of one of Australia’s most eminent economists, full of promises to power Australia's cheap renewable energy and create jobs in net-zero industries. The plan includes support for green hydrogen and the electrification of homes and businesses, both of which are critical to meeting Australia’s ambitious climate targets.

While the energy and climate commitments are significant compared to prior budgets, they no longer match up to the growing ambitions of some of Australia’s neighbours and allies. At best, they are a “down payment,” at worst another lost opportunity. Treasurer Chalmers is right to see enormous economic opportunities for Australia in the clean energy transition, but if he is serious about turning us into a “superpower,” he will need to produce a budget that competes with one: the United States.

Unsurprisingly, both Australia and the US are targeting the bulk of their spending on the power sector, the number one source of emissions in Australia at nearly a third of the annual total. Most of the $20.6 billion going towards electricity decarbonisation in Labor’s first two budgets is in the $20 billion ‘Rewiring the Nation’ strategy to provide low-cost finance for transmission investments.

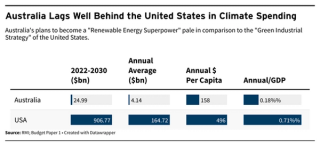

Any way you cut and slice it, Australia’s $25 billion in climate commitments announced in both the October 2022 and May 2023 budgets — as reflected in real dollar outlays, not targets, timetables, and promises — is a fraction of what the United States has legislated under the Biden administration. Between existing agency spending, the Inflation Reduction Act, an infrastructure bill, and the research & development spending authorised in the CHIPS and Science Act, the United States looks set to spend an extraordinary A$900 billion on climate-related measures between now and 2030. Relative to GDP, this is almost four times as much as Australia and more than three times as much per capita.

It is also instructive to see how the two countries’ climate spending is distributed. Unsurprisingly, both Australia and the US are targeting the bulk of their spending on the power sector, the number one source of emissions in Australia at nearly a third of the annual total. Most of the $20.6 billion going towards electricity decarbonisation in Labor’s first two budgets is in the $20 billion ‘Rewiring the Nation’ strategy to provide low-cost finance for transmission investments. The United States has taken a different approach, offering about A$90 billion in renewable electricity tax credits.

The US has also placed much more emphasis on transportation decarbonisation for reasons of both climate and economics. Largely by phasing out coal-fired power generation, the US now has lower emissions from coal power per capita than Australia and transportation is now its largest contributor to climate change. At the same time, transport manufacturing remains the US’ second-largest manufacturing sector and directly and indirectly employs over 10 million Americans. As a result, the Biden administration put considerable emphasis on spurring investments in the electric vehicle (EV) supply chain both to reach out to these manufacturing communities politically, but also to create new sources of economic opportunity and development in the energy transition. So far, it has been working. In just the 9 months since passing the Inflation Reduction Act, billions of dollars in new EV supply chain projects have been announced, promising over 142,000 jobs. What’s more, these investments have clustered in purple and red states that will be key to Biden’s re-election chances in 2024.

There are of course powerful economic (and political) reasons for focusing on debt and deficits in the latest budget, yet this fiscal conservatism is at odds with Labor’s ambitions to “reshape” Australia’s economy and embrace the “opportunities in the net zero transformation.”

These EV supply chain tax credits have been controversial in Europe and East Asia where domestic content provisions are seen to be protectionist, threatening not only their automakers’ market share but the very stability of the international rules-based order. The administration has demonstrated a willingness to extend some of these credits to key allies, such as the recent US-Japan Critical Minerals Agreement. Australia, on the other hand, is remarkably well positioned to enjoy the fruits of an EV boom in the United States, thanks to its abundance of critical minerals needed in the battery manufacturing process. Australia produces about half the world’s lithium, is the fourth largest producer of rare earths, and has about a fifth of the world’s cobalt resources, making it well-placed to reap the benefits of a heightened global critical minerals demand.

The single largest line item related to climate in this year’s budget, however, is Labor’s $2 billion ‘Hydrogen Headstart’ policy. Much was made under the previous Coalition government about Australia’s potential to be a major green hydrogen exporter, and businessman Andrew Forrest has been making global headlines with his ambitious plans for the clean feedstock in the Pilbara. These ambitions have been put at risk, according to Deloitte Economics, by the Inflation Reduction Act’s historic subsidies for green hydrogen in the US. Offering a production tax credit of US$3/kg of green hydrogen, RMI estimates this will be sufficient to make the feedstock competitive in shipping fuel, ammonia for fertilisers, and steel, which will dramatically accelerate decarbonisation in heavy industries. With some estimates suggesting the hydrogen tax credit could cost the US federal government nearly A$100 billion over its lifetime, it’s fair to say Labor has barely kept the industry afloat, let alone given it a running headstart.

While one doesn’t want to lose sight of just how refreshing it is to see the words “climate” and “decarbonisation” in a Budget statement again — let alone the words “renewable energy superpower” — these numbers are a reality check. There are of course powerful economic (and political) reasons for focusing on debt and deficits in the latest budget, yet this fiscal conservatism is at odds with Labor’s ambitions to “reshape” Australia’s economy and embrace the “opportunities in the net zero transformation.” Even as the Biden administration embraces a “new Washington Consensus,” Labor has delivered a “considered, methodical” budget though it will do little to fundamentally alter Australia’s position in the world, the drivers of its economy, or the trajectory of its carbon emissions.