Key takeaways

- The United States’ National Technology and Industrial Base (NTIB) is a congressionally-mandated policy framework that is intended to foster a defence free-trade area among the defence-related research and development sectors of the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom.

- To date, however, the NTIB has only managed to facilitate limited bilateral cooperation between some members, falling well short of its goal.

- The US defence export control regime is one of the biggest barriers to NTIB integration. Specifically, bureaucratic fragmentation, its failure to treat trusted allies differently from other partners and its leaders’ reluctance to attempt politically costly reform are significant barriers to progress.

- Canberra’s ability to maintain its own competitive military advantage and to serve as an effective ally of the United States in the Indo-Pacific is threatened by real and growing opportunity costs in an age of rapid strategic and technological change that Australia and Australian industry face as a result of slow NTIB implementation.

- Australian leaders should elevate NTIB progress to the political level and accelerate efforts to make a strategic case in Washington as to why extensive and ambitious implementation of NTIB’s original vision is urgently needed.

Introduction

The US defence industrial base is failing to draw upon one of Washington’s greatest strengths: its global network of trusted allies. In response, the National Technology and Industrial Base (NTIB) — a US legislative framework — was expanded by Congress in 2017 to include Australia and the United Kingdom. The two countries joined Canada, which was added in 1993, the year of the NTIB’s formation. The addition of Australia and the United Kingdom was a key allied component of a broader effort to equip the US Department of Defense with the tools necessary to maintain a conventional military-technological advantage in an age of growing strategic competition. It was premised on a strategic assumption that only some in the US system fully appreciate; namely, that for the United States and its allies to maintain a military-technological edge vis-à-vis great power adversaries, Washington must aggregate the research and development (R&D) and industrial bases of its allies, and incentivise the co-development of new capabilities. But since 2017, efforts to implement the legislation, break down decades-old export control barriers with allies, and establish projects beyond the bare minimum have been limited.1

The result is Australia and Australian industry face real and growing opportunity costs which hamper Canberra’s ability to maintain its own competitive military advantage and serve as an effective US ally in the Indo-Pacific. Australian leaders should elevate NTIB progress to the political level and further efforts to make the strategic case in Washington as to why more extensive and ambitious implementation of the original vision of the NTIB is needed.

The NTIB has only managed to facilitate some limited bilateral cooperation between members, far from the progressive multilateral framework it was intended to be.

The NTIB’s congressional authors intended for it to be a political platform for a renewed push for US defence industrial base and defence export reform, with the objective to emulate a “defence free-trade area”.2 But to-date, the NTIB has only managed to facilitate some limited bilateral cooperation between members, far from the progressive multilateral framework it was intended to be. The NTIB is defined as encompassing the people and organisations that are involved in national security and dual-use R&D, production and sustainment — or the defence industrial bases of the member countries broadly defined.3 But the actions to be taken under the NTIB, as it is written in legislation, are fairly narrow. The direction from Congress given to the US Department of Defense only states the requirement to submit a status report on the members’ collective defence industrial bases as well as propose new initiatives — like export control reform — for Congress to legislate on. Importantly, the expansion of the NTIB in 2017 did not make any material or legal change to Australia and the United Kingdom’s existing defence export relationships or joint-R&D efforts with the United States. Based on previous export control efforts, forming a defence free-trade area will take time, effort and political actors willing to bear some cost. But until then, the NTIB is in effect a framework with some utility, but significant unrealised potential.

There are multiple strategic reasons for Australia and the United States to pursue the NTIB. The first is that the defence industrial base of the United States — Australia’s main source of military technology — is under stress.4 Years of budgetary instability, lasting effects of sequestration and the US Department of Defense’s sluggish response to trends in the global distribution of R&D have left America ill-prepared for renewed strategic competition.5 Further, the rise of China as a competitor to the United States in industrial power and in the technologies underpinning the next wave of military modernisation is severely challenging a pillar of Canberra’s defence strategy: maintaining a regional military-technological edge.6 Another strategic reason to pursue the NTIB is the rising costs of next-generation military equipment, preventing the United States and Australia from buying new aircraft and naval warships in numbers that are effective. Lastly, the NTIB may be a tool for Australia in a region of growing uncertainty, adding knowledge and production in critical defence industry areas that Canberra may need sovereign control over in order to sustain military forces in times of need.7

The NTIB could become a progressive framework to address these strategic challenges. Further aggregating the R&D bases of the NTIB members, so they include more resources, people and can facilitate greater collaboration in a trusted and assured environment will lead to a more technologically competitive defence industrial base — and hence advance the cause of maintaining Australia’s military-technological edge. The rising costs of new military capabilities could be addressed by utilising the NTIB framework to provide incentives and access for competitive Australian companies to jointly develop, produce and sustain capabilities. Creating pathways within the existing US defence export control regime — or in special cases around it — may help bring down costs in critical capabilities overtime. The NTIB may also be a vehicle for the transfer of intellectual property and other knowledge to trusted allies as part of the development of their own sovereign defence capabilities, ensuring they remain capable strategic partners for the United States.

Yet, while the United States moves slowly in facilitating greater integration with its allies, the opportunity costs for Australia and Australian industry are growing. The longer serious progress on implementing the NTIB takes within the US system — either due to bureaucratic inertia or political resistance — the more Australia and other member nations will lack incentive to co-research, co-develop and integrate with the United States altogether. This is largely due to the extraterritoriality of the US defence export control regime and its ambivalence towards trusted allies. Ultimately, it is in the strategic interests of all NTIB members to quickly transform the existing minimal framework into a practical and effective multilateral defence cooperation zone.

The National Technology and Industrial Base

The term “NTIB” is described in US law as the combined research ecosystems and industrial bases of the United States, Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom in all of their constituent parts.8 A key amendment was added to the legislation in 2016 requiring the US Department of Defense to produce a plan and annual report on reducing barriers “to the seamless integration” of the organisations and persons of the NTIB.9 The report was required to specifically label changes to export control rules and laws that would improve civil-military integration among all members, including Australia.10 A report was released by the Pentagon in May 2019, but was minimal in its aims with no recommendations on export control reform or ambitious integration.11 This is, in effect, the essence of the NTIB at present: a congressional directive requiring the Pentagon to produce a forward-looking plan on breaking down barriers between the United States and its allies with some limited multilateral policy exploration between members.

Putting the NTIB into context

The NTIB is the allied element of a series of defence reform efforts championed by the late Senator John McCain in order to make the Department of Defense more competitive, agile and innovative in an era of great power strategic competition. While the NTIB is aimed at expanding the number of actors, resources and competitiveness of the US defence industrial base, other reforms focused on providing the Pentagon new tools in contracting and procurement for it to remain adaptive and innovative. Significant in themselves, these other reform efforts — specifically new defence contracting tools like Other Transaction (OT) agreements and Middle-Tier Acquisition authorities — have proven relatively more successful than the NTIB. For instance, OT agreements are generally exempt from some burdensome federal regulations and laws, allowing officials to amend contracts and bypass traditional requirements, tailoring them specifically to smaller, non-traditional defence companies.12 This allows for defence technology agreements that are more dynamic in scope, including joint ventures and partnerships between multiple government agencies and private enterprises, combining to fund ventures on specific capabilities and allowing the pooling of resources.13 OT agreements have been utilised by agile Department of Defense organisations like the Defense Innovation Unit to decrease the award time of US federal contracts and ensure the Pentagon keeps pace with the technology market by attracting start-ups to partner with the Department of Defense.14 Middle-Tier Acquisition agreements are similarly aimed at increasing the pace at which the Pentagon buys new equipment, allowing the rapid prototyping and fielding of new capabilities within two to five years — a relatively quick pace for US defence contracts.15 While these two reforms have been successful — OT agreements have grown from 12 issued in 2013 to 94 in 2017 — and are complementary to the NTIB, the NTIB itself faces a far more difficult bureaucratic path.16

The NTIB’s congressional authors were ambitious when they directed the Pentagon to find new ways to increase industrial integration with its closest allies. There are several hurdles that must still be navigated, namely the fact that the Department of Defense and the Armed Services Committees of Congress have little legislative power over defence export controls; the main impediment for further defence integration with close allies. Most defence export controls are governed under a separate legal authority than that under which the NTIB was implemented. The majority of US defence exports are administered by the State Department through the Foreign Military Sales and Direct Commercial Sales programs, the path by which most foreign governments purchase defence equipment from the US government. The State Department also has authority over the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), which regulate the licensing of exports on the US Munitions List, including capabilities such as guided missiles, electronics and launch vehicles. Critically for US allies, ITAR considers the nature of the article in question not “the end-use or end-user of the item”, meaning allies are largely considered by the export control system on an equivalent basis with other countries.17 Further, it is “extraterritorial” in its application, meaning that if knowledge or a product is labelled under ITAR at the R&D stage (through the involvement of a US person or entity anywhere in the world) it is controlled under US defence export controls through its entire product life-cycle, permanently.18 At present, the NTIB does little to address this inflexibility. The system is further fragmented through the control of dual-use items, which are administrated by the US Department of Commerce through the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) and include technologies as diverse as propulsion systems to microorganisms.19 Although the US Department of Defense has a say in this complex export control regime, and reviews the licensing, sales and export processes that are administered by the other two departments, it is ultimately an interagency process over which no single entity has control.

Setting expectations: The Canadian example

Canada is the only US ally that has, to date, successfully found a partial equivalency within the US defence export control system. Its experience, however, highlights the limits to defence industrial base integration, and is not an example of viable pathways for other allies. Canada was incorporated into the US defence industrial base in 1993, when Congress established the NTIB framework following the consolidation of the North American defence industry after the drawdown in military spending following the Cold War. This built on and formalised the already highly interconnected defence industries between the two countries, which originated during the Second World War with the Hyde Park Agreement and the Defense Production Act.20 A key feature of Canadian-US defence industrial integration, besides geography, has been Ottawa’s ITAR exemption. Canada has been able to negotiate and maintain this exemption by effectively replicating US defence export control institutions and establishing entire government departments and organisations — namely the Controlled Goods Program and Canadian Commercial Corporation — in order to fulfil onerous US standards and requirements.21 For Australia to achieve similar exemptions in this way would require the establishment of comparable bureaucracies; an expensive and burdensome endeavour that would not be practical for the less-integrated defence industry relationship Canberra has with Washington.

Both treaties did make efforts to align security practices and exemptions from licensing and regulatory hurdles for UK and Australian companies, but similar to Canada’s ITAR exemption, core technological areas were absent from the treaties and complex implementing agreements limited their appeal to industry.

Canada’s long association with the United States, including through the NTIB, has led to the development of defence industrial linkages that have been utilised in times of need. For example, Canadian industry played a “surge” role for the Pentagon during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, building and armouring vehicles for the US Army and Marine Corps when US facilities were at maximum capacity.22 Nonetheless, Canada still faces barriers to defence trade cooperation with the United States and its ITAR exemption does not cover classified services and technical data, missile technology and aircraft components, among other items.23 Ongoing limits to integration include persistent regulatory hurdles, a poor understanding of Canada’s status among US defence acquisition offices, and disagreement over what constitutes a small business within both countries systems.24

Efforts by Congress throughout the 2000s to build exemptions and status in the US defence export control regime for Australia and the United Kingdom have encountered similar hurdles. In 2007 Congress passed separate defence trade and cooperation treaties with Australia and the United Kingdom, but these failed to achieve lasting reform.25 Both treaties did make efforts to align security practices and exemptions from licensing and regulatory hurdles for UK and Australian companies, but similar to Canada’s ITAR exemption, core technological areas were absent from the treaties and complex implementing agreements limited their appeal to industry.26 In addition, efforts by former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates to correct the fragmentation in US defence export controls by creating a unified agency and controlled technology list also failed to achieve their aims.27

Continuing challenges for NTIB implementation

The history of attempted defence export control reform may help explain the slow development of the NTIB since its expansion in 2016. While the US Department of Defense published a report on progressing the NTIB as mandated by Congress, it was largely buried in other defence industrial base analysis, indicating a lack of prioritisation. Furthermore, the NTIB report was minimal in its goals, likely reflecting both the constraints it is operating under and a lack of urgency in the US Department of Defense.28 In 2017, for instance, the four member states of the NTIB met to develop a “statement of principles and strategic construct” as first steps to building governance arrangements.29 This led to a principals meeting between the NTIB members later that year that established four “pathfinder projects” that the members agreed to explore on a multilateral basis, including new avenues of controlled technology transfer, synching investment security practices through Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board and the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, building cybersecurity in small and medium enterprises, and establishing an NTIB coordination mechanism.30

While these are laudable first steps to take place under the NTIB framework in a multilateral sense, prospects for further progress in the short-term appear slim. Worryingly, a decision was taken in 2019 to “down-scope” the pathfinder projects and focus on just two areas: foreign direct investment review and technology transfer.31 The technology transfer discussion is a positive development for defence industrial base integration and may well help to resolve a longstanding issue. By contrast, foreign direct investment review alignment could be handled in other fora. In both cases, these issues are relatively low-hanging fruit and likely reflect the statutory limits on the Pentagon’s power when it comes to the core issue preventing deeper integration: defence export controls. Without reform to the fragmented export control system or direct involvement by Congress, the State Department and the Department of Commerce, there are limits to what the US Department of Defense is able to achieve when it comes to the NTIB and its original vision as a vehicle for serious reform for a new age of strategic competition.

Growing opportunity costs for Australia

While the expanded version of the NTIB is still relatively new, there are growing opportunity costs for Australia and the United States as the process of implementation lingers. For instance, as close allies like Australia continue to be treated the same as other countries by the US defence export control system and its extreme extraterritorial application, they will undoubtedly treat collaborating with the United States and US persons as a risk and a barrier, rather than an enabler.32 Collaborating with US persons and companies, and the risk of being brought under regimes like ITAR, will increasingly make little business sense for innovative — and in some cases more advanced — companies in Australia, the United Kingdom and Canada. But strategically, in order for the United States and its allies to retain their military-technological edge, they will increasingly need each other as a means to co-develop and invest in complementary capabilities that leverage their respective scientific, R&D and industrial knowledge and expertise. This is because the diffusion of global R&D and the rise of a true scientific and industrial competitor in the form of China is challenging the United States’ ability to maintain its defence enterprise on its own.

On the macro-level, the United States must harness and aggregate the R&D bases of its allies, break through barriers to incentivise them to invest in co-development and in some cases co-manufacturing of new systems, and build their sovereign capabilities to make them more effective strategic partners. There is little doubt that there will be hard limits to NTIB integration in core areas of traditional defence industry labour, like naval shipbuilding, which are highly regulated and protected in many countries.33 But the strategic challenges facing Australia and the United States require a major change in their willingness to execute politically difficult reform over how NTIB countries can work together. The first opportunity is to harness a larger and more dynamic defence industrial base to lower the cost of new military systems before defence export control restrictions make co-development and investment between NTIB countries impractical. Secondly, the NTIB is an avenue to facilitate the strengthening of Australia’s own defence industrial base in critical areas that can support joint military operations in the Indo-Pacific. But without further integration, the ability of Australia to aggregate its capabilities with other regional partners will become more costly, and may force Canberra to consider alternative pathways in the region, reducing interoperability.

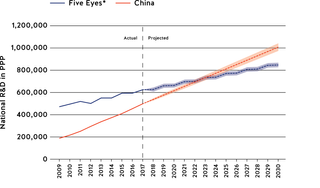

Figure 1. Trends in national research and development

Reducing the growing cost of next-generation military systems

One of the most urgent priorities for the United States and Australia that an effective NTIB could solve would be to lower the development and sustainment costs for next-generation military systems. The cost to build and maintain many new military capabilities is growing above inflation.34 This is a trend challenging the United States and its allies as it is stretching limited resources and pressuring the capacity of defence forces to buy, field and sustain military systems in sufficiently high numbers to deter China’s rapidly modernising military.35 New combinations of technologies and capabilities are emerging that may help Australia, the United States and other allies field systems at financially sustainable rates. But increasingly some of these capabilities are being advanced through co-development between the United States and its allies as a way to cost-share and capture cutting-edge expertise and technologies outside of the United States. Going forward, due to the extreme nature of US defence export controls, it will be progressively costly for allies to engage in these programs with the United States as questions arise over where these capabilities will be built and under which country’s control. This will stifle much needed collaboration, burden-sharing and the development of parallel programs, none of which will help address structural cost inflation issues facing the defence forces of all NTIB members.

Though the F-35 was designed from the outset to cost-share among 16 nations and drive cross-border collaboration, participating companies “still had to seek transactional licenses at every stage of the process” through the US defence export control regulatory system.

In 1983, former US Department of Defense official and defence industry executive Norman Augustine predicted that due to the intergenerational growth in costs for fixed-wing fighter aircraft, by 2054 “the entire defence budget will purchase just one aircraft”.36 This concept is the ‘cost-capability curve’ that has largely governed aircraft development — along with naval construction — for the past 40 years. For example, the F-35 is projected to cost US$64 billion (2017 dollars) to develop, whereas the fighters it is replacing — platforms like the F-18, F-16 and A-10 — had a collective development cost of US$21 billion (2017 dollars).37 A 2008 RAND study commissioned by the US Air Force and US Navy found military aircraft costs had grown by seven to 12 per cent on average over the past several decades, doubling the rate of inflation.38 US naval shipbuilding has historically followed a similar trend; since the 1950s, the cost to build amphibious vessels, major surface combatants and attack submarines has grown from seven to 11 per cent.39 This has left many new capabilities in prototyping and experimental phases as governments have found it too costly to outlay the necessary level of funds to reach sustainable levels of manufacturing. Only once many of these systems are produced at high-quantities do they begin to capture the economies of scale that make them affordable.40

The growing above-inflation rise in development and procurement costs has, in part, caused a crunch in the size or capacity of defence forces across the NTIB. For instance, the United States is slated to procure just under 2,500 F-35s to replace 4,200 air frames of various types like the F-18 and A-10.41 The costs for other modernisation programs grew so much that they were halted before the full production run was completed, like the F-22 which the US Air Force originally projected to procure 750 air frames to replace the F-15 in the air-dominance role but ended up with 187.42 The Royal Australian Air Force and Navy have likely only escaped similar problems because Australia’s defence budget has grown.43 The navies of the United Kingdom and the United States have not been so lucky. For example, the shift in naval force structure design since the end of the Cold War to multi-role and high-end exquisite platforms has resulted in smaller navies that are now experiencing overstretch; the US Navy shrunk from 594 vessels in 1984 to around 290 today and similarly the Royal Navy could marshal 115 ships in 1982 but had shrunk to 90 by 2016.44

Properly conceived, the NTIB should take advantage of new manufacturing technologies and military capabilities that could bolster the capacity of NTIB members. Previous models of joint development and procurement like the multi-national F-35, which are designed from the outset to share the burden of developing a next-generation aircraft, are no longer fit for purpose considering the changing pace of capability design and development as well as the need to bring non-traditional defence suppliers into the industrial base. For instance, though the F-35 was designed from the outset to cost-share among 16 nations and drive cross-border collaboration, participating companies “still had to seek transactional licenses at every stage of the process” through the US defence export control regulatory system.45 Technology transfer disputes also threatened to upend the program — a good example of the opportunity costs for allies associated with existing US defence export controls. In 2005 the United Kingdom — the most senior F-35 program partner with an investment in the development costs of the program of more than £1 billion — threatened to withdraw from the development over technology transfer and ITAR issues.46 UK withdrawal from the program would have had significant negative impact on the cost-sharing goal at the heart of the F-35 program. As the F-35 is software intensive, the “independent” maintenance of the fighter and integration of new capabilities over time requires access to the plane’s source code, the transfer of which the United States was unwilling to make to the United Kingdom. While workarounds and compromises were eventually found and the United Kingdom remained with the program, the episode is likely to repeat itself in other joint-programs as costs are increasingly required to be shared among NTIB countries in the development of new capabilities.

Australia should work with its NTIB partners to ensure the next generation of defence capabilities are affordable in mass, add capacity to overstretched defence forces and encourage new forms of design and production.

Australia should work with its NTIB partners to ensure the next generation of defence capabilities are affordable in mass, add capacity to overstretched defence forces and encourage new forms of design and production. Programs such as the Air Power Teaming System or ‘trusted wingman’ — a low-cost unmanned ‘attributable’ aircraft and joint development between the Royal Australian Air Force and Boeing — are an example of emerging technologies designed from the outset to lower the cost of mass-produced military systems.47 The assumption has been that this new system would be manufactured in Australia, though Boeing executives have stated that the production location will depend on the export “market”, likely reflecting the eventual ITAR restrictions the system will fall under.48 If the system is to be manufactured in the United States due to ITAR restrictions, it will undoubtedly still help lower costs and add numbers to a stretched RAAF fighter force. But repeated examples of these arrangements will likely disincentivise allies from entering new co-development programs with American companies. This will in turn work against the benefits and need of aggregating R&D and the economies of scale associated with joint-development. Similarly, Australia and the United States are experimenting with hypersonic-capable systems through a consortium based at the University of Queensland in partnership with the US Air Force Research Laboratory, DST, BAE Systems Australia and Boeing.49 As the research from this partnership leads to further prototyping and potentially production, similar questions will also likely arise as to where it will be built and under what controls. If access to manufacturing is restricted and controlled by the United States due to defence export controls, these joint-development examples are likely to decrease in the future as the opportunity cost grows for Australia.

Considering the present state of the NTIB, these are ambitious topics for its principals committee to tackle. Starting with relatively smaller issues, such as allowing allies to participate in the new transaction authorities granted to the Pentagon, may be a more promising way for the NTIB’s negotiators to address some underlying issues associated with the rising cost of new military systems.

One such vehicle of note is the Cornerstone OTA program. Established by the Pentagon in 2018 in response to the needs of the US National Defense Strategy and the erosion of the US industrial base, Cornerstone is a defence consortium designed as a public-private partnership that takes advantages of flexible contracting authorities, combining government funding and oversight with the aggregation of non-traditional defence suppliers.50 It was established to fund programs and pilot projects on critical gaps in the US defence industrial base where it allows for the aggregation of proposals from companies ranging from defence primes to small start-ups with niche capabilities. Promisingly, the Cornerstone program is one of the first “other transaction authorities” to specifically extend to NTIB countries, writing it into the foundation agreement. Reportedly, it has been utilised to procure flares from NTIB members to plug gaps in the struggling F-35 supply chain, showing its early promise.51 Ensuring Australian companies can obtain unclassified US tender documents — a known issue as they are controlled under ITAR — would immediately help facilitate integration under these consortia.52 Facilitating further expansion of NTIB authorities to other government-led consortia and novel transaction authorities are promising first steps towards alleviating the opportunity costs facing allies in the joint-development of new capabilities.

Supporting Australia as a credible strategic partner

The slow progress of the NTIB could prove ultimately harmful for the United States in that it could stunt Australia’s ability to strengthen its own sovereign industrial capabilities. In recent years, Australia — through its 2016 Defence White Paper and Integrated Investment Program — has moved more openly towards a sovereign and export-orientated defence industrial policy, with the strategic goal of being able to support its own independent military operations in the region if necessary.53 Allies with the capabilities to sustain independent operations in their near regions — through the maintenance of joint-capabilities like the P-8, F-35 or the production of highly consumable resources like munitions — are ultimately more capable strategic partners for the United States, with greater ability to respond to regional crisis, fill gaps in US defence supply chains and act as regional maintenance hubs. As such, Washington’s slow rolling or unwillingness to progress the NTIB as a vehicle for strengthening its allies weakens the value partners like Australia can bring to the United States. It also incentivises allies to seek alternative pathways in military capabilities, harming interoperability and aggregated defence in the region. Tailored programs and licence exceptions in key capability or sustainment areas are in the interests of both Australia and the United States insofar as they support sovereign capability and bolster the latent capacity and resilience of the wider NTIB network.

Tailored programs and licence exceptions in key capability or sustainment areas are in the interests of both Australia and the United States insofar as they support sovereign capability and bolster the latent capacity and resilience of the wider NTIB network.

Without an effective NTIB, Australia will be limited in how it can contribute to regional crises in support of the United States, making up for shortfalls in maintenance capacity and highly expendable munitions. Australia’s 2016 Sovereign Industrial Capabilities requirements push the needle towards seeking a higher degree of self-reliance, directly linking defence industrial policy to capability. The definition of sovereign capabilities does not require the “local generation or retention” of intellectual property, only local “access” or “control” of priorities like aerospace platform deep maintenance, the testing and assurance of systems and munitions, and small arms research, design, development and manufacturing.54 Yet, in highly consumable areas — like munitions — this policy may fall short, particularly when access to supply within the wider NTIB network is strained. Although the Australian Defence Force (ADF) plans on the assumption of being able to access US supply for many of the consumables that a modern military campaign would require — such as “spare parts, precision-guided munitions or sonobuoys” — existing stockpiles are likely to be insufficient for an extended high-end warfighting campaign and are “based on minimal levels strongly influenced by peacetime training rates”.55

The risk of relying on US stocks for critical warfighting consumables were demonstrated during the recent operations against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. Due to a variety of factors, including structural limitations in the US defence industrial base, the ADF was left without an assured supply of precision-guided ground attack munitions and turned to local defence industry to quickly address the shortfall. Critically, because of technical data restrictions due to US export controls, local government and industry experts were forced to stand-up manufacturing lines without foreign assistance. In this instance, Australian industry was able to respond in a relatively short period of time to the urgent request, resulting in the successful manufacture of the first-ever plastic bonded explosive fill utilising all Australian explosive components. However, time pressures in a future conflict and the complexity of the kind of munitions required in a high-end operation would more than likely outstrip current capability. A properly functioning NTIB could address this problem by facilitating technology and data transfer for trusted allies — making it possible for Australia to continue contributing to priority coalition operations and backfilling US munitions shortfalls in service of Australian and American interests.

Achieving this will require a focused reduction in technology transfer barriers. For instance, to date, Australian industry possesses little experience in the “software development and management” that underpins modern precision missiles.56 Any software that does cross the border from the United States is controlled and on a government-to-government basis to aid with the management and light maintenance of weapons, like with the Harpoon anti-ship missile.57 Concerningly, if deeper maintenance on a weapon is required, they are shipped back to the original manufacturer, “a process that can take up to 18 months”, an unsustainable timeline during a high-intensity conflict.58 If Australia were to develop a domestically-based credible munitions capacity it will likely require access to US intellectual property and data, particularly software. However, the defence export control restrictions placed on that technology and any subsequent development would make the business case unviable and further restrict Australia’s ability to bolster its ability to support regional contingences.

If a production capacity such as this were developed in Australia, it would simultaneously advance Canberra’s objective to bolster its sovereign defence capabilities as well as generate latent capacity for the United States in an identified area of weakness within its defence industrial base.

Furthermore, an effective NTIB should move beyond local production of US systems to help key allies like Australia to build out and fill the gaps in new emerging munition capabilities. A top priority would be lightweight guided munitions with the ability to be fielded in large numbers at low cost. If a production capacity such as this were developed in Australia, it would simultaneously advance Canberra’s objective to bolster its sovereign defence capabilities as well as generate latent capacity for the United States in an identified area of weakness within its defence industrial base.59 The NTIB member countries could explore how similar tools like the Strategic Trade Authorization License Exception in the Department of Commerce — an Obama-era reform that aided in the release of software code and technology to trusted foreign partners — could be applied to these scenarios.60

A networked approach to the production of lightweight munitions could be explored — with Australia hosting manufacturing and sustainment facilities that could be accessed by NTIB members, and with a share of IP royalties flowing back to US or other joint-development partners. As with the Air Power Teaming System and Canberra’s efforts to maintain an on-shore high-explosives and propellent capability, it will likely take an investment from Australia’s Department of Defence to begin building a capacity in Australia to design and manufacture even a lower-end guided smart munition. This is the type of viable business and strategic case that the NTIB framework of trusted allies can help bring over the line with US industry and regulators. These types of projects will improve supply-chain resilience and ensure Australia remains an effective strategic partner in the Indo-Pacific.

Conclusion and recommendations

There is a long history of the United States drawing upon the defence industrial bases of its allies when in need. The munitions and explosive facilities in Whyalla and Benalla — recently updated to modern standards — were first built to support the American military campaign in the Pacific during the Second World War. The strategic challenges facing Australia and the United States in the Indo-Pacific today, along with the global diffusion of technological and industrial power, present a renewed case for close US allies to seek innovative ways to aggregate their collective defence industrial capabilities. The expansion of the NTIB to include Australia and the United Kingdom has laid the groundwork for larger reform and integration with allies. But while allies and officials within the United States can continue to press for further reform, it will ultimately take political will in Washington to push for a major overhaul of the US defence export control regime to bring it in line with the requirements of great power competition. Breaking down barriers and incentivising trusted allies with the R&D, knowledge and resources to continue working with the United States should be a critical priority. Australian policymakers can influence this process in three ways:

First, Australia and other NTIB members should focus advocacy for NTIB progression on members of Congress in the House Foreign Affairs and the Senate Foreign Relations Committees, as well as on officials in the State Department. While the NTIB’s coordinating officials and functions are housed in the Pentagon, authority over further reform of defence export controls — the most significant impediment to deeper NTIB integration — are located within those parts of the government responsible for foreign affairs. This fragmentation of US defence export control policy makes it difficult when Australian officials are interacting with their counterparts. For example, Australia’s defence industry and export officials are located within the Department of Defence, with DFAT having little responsibility for the importation and exportation of defence articles. Advocating the need to aggregate allied defence industrial capability in order to retain a military-technological advantage in the Indo-Pacific should be a priority for allied officials in Washington.

Second, Australian leaders should raise further NTIB integration and prioritisation at the political level as an industrial capability priority. Annual AUSMIN consultations would be the best venue for this discussion. In a recent speech in the United States, Australian Defence Minister Linda Reynolds linked the furtherance of the NTIB to Australia’s ability to be an effective partner of America in the Indo-Pacific, saying “more effective industry cooperation will be a critical component of the more potent combined effect we will need for deterrence purposes”.61 Elevating the NTIB to fulfil this aim, and allowing members to combine resources to further deterrence effects in the Indo-Pacific, should be a focus of Australian defence and foreign ministers when meeting with their US counterparts. One avenue would be to press for more senior representation within the Department of Defense for responsibility for the NTIB, thus allowing higher-level buy-in beyond the working level.

Finally, Australia and other NTIB members should expand beyond the exploratory work being undertaken on direct financial investment review and technology transfer to thinking about strategic initiatives with viable business cases that the policy framework can facilitate. Critical minerals and rare earths — an area of growing cooperation between Australia and the United States — is an example where the NTIB can enable and match up supply and demand between members.62 A contemporary example is a tender currently out to market through the Cornerstone consortium regarding the construction of a rare earths processing facility in the United States. This is an example of NTIB countries like Australia having the requisite skills and expertise to bid on a pressing defence industrial base gap in the United States. A simple but effective reform to work through would be to find ways to open up unclassified tender documents that are often restricted by ITAR to Australian and other NTIB countries allowing companies to more easily bid for consortium projects like the Cornerstone rare earths facility. Broadly, ensuring the NTIB allows the formation of key joint-capabilities should be its major focus.