Key takeaways

- The November midterm elections will provide the first national indicator of how President Donald Trump’s messages and disruptive style have resonated with the wider public.

- Trump’s antipathy to alliances, opposition to free trade and affinity for authoritarian strongmen obscure larger debates and emerging trends about America’s engagement with the world. These larger debates about America’s role will continue long after Trump is gone.

- American attitudes on internationalism reflect ambivalence, not rejection. Such ambivalence is hardly without precedent over the past 70 years.

- The sustainability of any future US foreign policy will turn on the interplay of political support, economic circumstances, geostrategic threats and political leadership.

- While America’s debate about its role in the world will persist beyond the 2020 presidential election, Australia and other allies can do much to influence that debate.

Introduction

Donald Trump’s presidency has raised profound questions about the role the United States will play in world affairs, and whether his election and isolationist vision represents an anomaly or is indicative of deeper structural shifts in American attitudes about the country’s global role.

The first answer to these questions will come in the upcoming US midterm elections in November.

Trump and the US presidency: The past, present and future of America’s highest office

In this case, the elections will also provide the first national indicator of how Trump’s messages and disruptive style have resonated with the wider public. More importantly, the outcome will have concrete implications for the Trump White House – either further empowering it to pursue its domestic and foreign policy agendas, or by checking it through the election of a Democratic congress. As such, the 2018 midterms are being called a referendum on the Trump presidency, which for some Americans will primarily be a verdict on US domestic policy under Trump. But it will also indicate whether the American people are seeking a correction on the direction of Trump’s foreign policy.

The midterms will not offer definitive answers to the ongoing debates about America’s role in the world, but they will illuminate some underlying trends: What exactly Trump means by “America first”, how widely those sentiments are shared, and the debate surrounding the sustainability and wisdom of America’s global role. But other political, financial, geostrategic factors will also shape American power in the twenty-first century. And US allies can play an important role shaping the direction of this debate, as they increase their own commitment and ability to defend and promote the rules-based order.

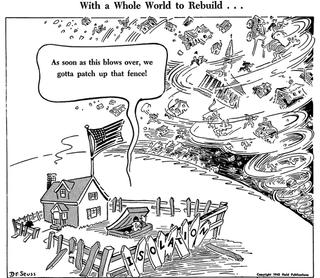

The first America first

It was during the 2016 presidential campaign that Donald Trump began using the phrase “America first”, to characterise his view of foreign policy. By resurrecting the phrase, he echoed the mantra of the group that opposed American entry into World War II prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor.1 Others have noted that this is a loaded phrase, as this group championed an isolationist approach to world affairs that excused authoritarian states and encouraged anti-Semitism.2 Trump has claimed that he did not attach any particular meaning to the phrase, other than that he liked it.3 His previous national security and economic advisors H.R. McMaster and Gary Cohn attempted to explain that “America first doesn’t mean America alone.”4 While “America First” is clearly associated with the isolationist wartime movement, it is ultimately America’s post-war role that Trump questions.

While some of Trump’s impulses may be warranted – increasing the US defence budget and a stated willingness to confront adversaries when necessary – the president does not seem willing to engage the world, rally traditional allies and support democracy against those who would work to undermine it.

In the 1930s, dictators drew support from US abstention, carved out spheres of influence, suppressed democracy and, ultimately, took the world to war.5 It was only after that great tragedy that Americans were willing to change course and embrace a very different foreign policy in the following decades. This new foreign policy recognised that the national interest required US engagement with the world, robust defence budgets, economic cooperation, alliances with like-minded states and the unapologetic defence of American values abroad. This post-war vision embraced American leadership, embedded the United States in a series of security commitments, supported collective defence, worked to restrain arms races, participated in multilateral institutions, promoted trade between countries, championed democracy and human rights, and advocated for the rule of law. While the efforts were not always pursued consistently, the general principles of the post-war order were clear: protectionism killed jobs, it was dangerous to allow any single country to dominate a region and establish a sphere of influence, democracies were more likely to act peacefully, and where nations voluntarily gave up some of their power to ensure that rules applied to everyone. The United States embraced a lead role in promoting these ideas and has largely benefitted as a result.

It is this vision that President Trump has continuously attacked as a bad deal for America. He has raised questions about its security commitments, explained trade solely in terms of economic loss and displayed an indifference to human rights, while expressing admiration for multiple autocratic rulers. While some of Trump’s impulses may be warranted – increasing the US defence budget and a stated willingness to confront adversaries when necessary – the president does not seem willing to engage the world, rally traditional allies and support democracy against those who would work to undermine it.

Supporters of the president often argue that observers should look at what he does, and not what he says. Others point out that Trump’s foreign policy often seems divorced from what the US government is doing on a day-to-day basis and note that his administration has put out formal strategy documents – the National Security Strategy and the National Defense Strategy among others – that are robust expressions of American internationalism.6 But that does not mitigate Trump’s consistent antipathy to alliances, opposition to free trade, and affinity for authoritarian strongmen. As the Brookings Institute’s Thomas Wright has written, Trump “is often shocking but rarely surprising”.7 And because of that, many worry that Trump has put the United States on the precipice of withdrawing from global leadership.

Such concerns are inevitable, and will continue for as long as Trump remains president. But they also obscure larger debates and emerging trends about US engagement with the world. And it is these larger debates about America’s role that will continue long after Trump is gone.

New circumstances; old debates

In terms of world affairs, the most salient questions revolve around the sustainability of US power and the durability of its commitment to the role it has played for the past seven decades; for friends, out of anxiety over potential abandonment; for foes, out of a sense of opportunity. There is widespread concern that Trump’s views are not his alone, but are symptomatic of a growing share of Americans no longer willing to bear the burdens and pay the price of global leadership. For many Americans, fatigued by years of unending war and distressed by economic hardship, this may seem like an attractive prospect.

Such debate is part of a regular and recurring conversation over both the sustainability and the advisability of America’s global role. As US scholar Stephen Sestanovich points out, it is a debate that always revolves around the same doubts about whether the US economy is big enough to sustain a global role, if domestic problems should take priority over foreign ones, whether the public is yet ready for “new exertions”, and if American leadership is sufficient to solve complex international challenges.8 However, this important debate has been obscured rather than answered by Trump’s dominance of news cycles. 9

This might be a familiar debate in the United States, but it is not a trivial one. Many Americans have forgotten what the US-led international order was meant to prevent in the first place: the complete breakdown of the international system and the descent into great power war that occurred not once, but twice in the twentieth century.

This might be a familiar debate in the United States, but it is not a trivial one. Many Americans have forgotten what the US-led international order was meant to prevent in the first place: the complete breakdown of the international system and the descent into great power war that occurred not once, but twice in the twentieth century. Considering its longevity and its relative success, it is not surprising that many Americans have come to take it for granted.10 Trump is not alone in questioning the costs, value, and sustainability of America’s role. Attacking the effects of globalisation, questioning the value of US security guarantees to its allies, railing against the inefficiency of multilateral institutions, and doubting whether the United States can afford nation-building efforts abroad, Trump has articulated long-standing critiques. After Trump’s trip to the NATO Summit in July 2018, a survey found that “49 per cent of [American] respondents said the United States should not have to uphold its treaty commitments if allies do not spend more on defence” while “18 per cent said they were not sure if the United States had to uphold those commitments”.11

This argument resonates because the United States does pay a disproportionate share of costs to uphold this open, stable, and integrated system. That’s true militarily, in terms of defence appropriations in absolute terms and as a percentage of its overall budget, in terms of subsidising allies who have not been willing to shoulder a larger share of the burden for their own defence, and in paying some of the heaviest costs in response to the outbreak of hostilities. It’s true in an economic sense, by being willing to keep its markets open even to those who have refused to do likewise, moving at the forefront of a globalised economy while enervating the manufacturing sector and displacing American workers, and taking responsibility for global financial stability and liquidity. And, it is true from an institutional sense, where the United States has accepted constraints on its power.

Of course, there are immense benefits that the United States derives from this system. But that is not to say that leadership has come without costs. It is because of these factors, the American historian Hal Brands has written, that American attitudes on internationalism, “reflect ambivalence and dissatisfaction, not total rejection”.12 Such ambivalence is hardly without precedent over the last 70 years; attuned to the political dynamics inherent in forging sustainable grand strategy, Eisenhower lowered US expenses and commitments after the Korean War, Nixon shifted burdens to regional allies after the Vietnam War, and Obama scaled down US commitments in the wake of Iraq and Afghanistan.13 It is too soon to tell if this represents a fundamental inflection point for America’s post-war international role, or if it instead heralds a return to earlier debates about its sustainability.

It is clear that the terms of the debate have been recast and certain questions will be asked more frequently, and more sharply, in the future – and the United States may see the pendulum swing back towards a more isolationist approach. On trade, the debate will increasingly focus on how to counter the mercantilist policies that China and others have pursued while benefiting from access to US open markets.14 As the advanced economies of the world shift towards automation and artificial intelligence, the discussion will revolve around questions of how to offset the losses of workers in easily automated professions, such as low-skilled manufacturing. On appropriations, the domestic US argument will continue to pit spending on social security and health care against defence dollars. In terms of alliance relations, it will call for a greater willingness by allies to invest more in their own security. From an institutional perspective, US policymakers will continue calling for reform of process-heavy organisations. And, as great power competition returns to the Asia-Pacific region and Europe, the American debate will increasingly revolve around the question of whether a world defined by spheres of influence is more or less stable, and more or less conducive to US interests.

The future of US foreign policy

The sustainability of any future American foreign policy will turn on the interplay of political support, economic circumstances, geostrategic threats and political leadership. Here, history suggests that the contours of the future US foreign policy debate – and role that the presidency has in shaping those debate – are as likely to be shaped as much by exogenous factors as they are by internal ones.

In 1943, the American political commentator Walter Lippmann pleaded for "bringing into balance, with a comfortable surplus of power in reserve, the nation's commitments and the nation's power". He demanded that “the nation must maintain its objectives and its power in equilibrium, its purposes within its means and its means equal to its purposes, its commitments related to its resources and its resources adequate to its commitments".15 As Lippmann understood more than seven decades ago, US foreign policy will remain the product of how well its policymakers can calibrate the supplied means to the desired objectives. But of course both resources and commitments are constantly in flux.

If economic growth rates stagnate in absolute and relative terms, foreign policy options will narrow as resources shrink. Conversely, if US economic growth continues to increase relative to others and in real terms, the number of options available to policymakers would quickly change. This also holds true in terms of mandated federal spending on entitlements, which squeeze discretionary spending.16 If the US government can find a path to more sustainable spending on entitlements, and if the United States can begin to get its long-term fiscal health in order, strategy becomes less resource constrained. Moreover, long-term US demographic and cultural strengths and emerging trends in the energy markets suggest that the future is not necessarily one of limited growth.17

US foreign policy does not occur in a vacuum, but in reaction to events. For the first five years following World War II, defence budgets remained remarkably low, despite the increasing aggressiveness of the Soviet Union.18 But when North Korea invaded South Korea in June of 1950, President Truman became convinced that defence expenditures needed to increase immediately. The outbreak of the Korean War provides a clear example, but so too do the shocks of Pearl Harbor and 9/11. All three of these events reconfigured not only the demands of national security, but also the resources available to it. None of this is to argue that America’s history of resilience portend a cure for its current political, economic, and strategic doldrums.19 An increasingly fraught security environment, where threats multiply and become more complex, compounds the challenge.

Finally, political leadership plays a role. It is hard to expect the public to support positions that leaders are not willing – or only partially willing – to defend. It has always been a hard argument to support the defence of faraway countries because it is about the preservation of something that may seem intangible, and yet nevertheless is essential to the security, prosperity and values of democratic nations: support for a rules-based order. It is also hard because it asks the public to imagine the tragic outcomes that would occur without sustained US engagement. This was an easy argument to make after two world wars – but a more challenging one today as the searing experience of those two tragedies fade from our collective memories. But without that vocal leadership making such arguments, it is a much more challenging case to make.

Towards 2020

Australia and other allies should expect that the debate about America’s role in the world will continue beyond the 2018 midterm elections and through the 2020 presidential election. This debate will persist regardless of the size and shape of the US defence budget.

In 2016, Pew Research polling found that 57 per cent of Americans believed that the United States should “mind its own business internationally and let other countries get along the best they can on their own”.20 This result revealed some of the most pronounced anti-internationalism in the United States in generations and suggested that Americans are increasingly focused on tending to their own affairs, and not the world’s.

The more Asian and European allies can do to fund and provide for their own security needs, the more they will be seen as equal partners to the American public, the national security community, and aspiring presidential candidates.

However, Americans are not necessarily fleeing the world yet, nor are they rejecting the post-war order completely. When Americans are asked if they support US alliances, prefer free trade to protectionism and believe Washington should possess the world’s most powerful military, they answer yes, often by considerable margins.21 But Americans are becoming more resistant to the sacrifices and trade-offs necessary to preserve the stability of the post-war world order.

For friends and allies of the United States who have a vested stake in preserving the rules-based order, there is much that can and should be done. The more Asian and European allies can do to fund and provide for their own security needs, the more they will be seen as equal partners to the American public, the national security community, and aspiring presidential candidates. If US allies increase their defence budgets and capabilities, and demonstrate a greater willingness to seek security arrangements that promote an open and stable international order, this will have a positive impact on the perception of future American administrations. More importantly from their perspective, doing so will increase their influence in Washington and simultaneously allow them to hedge for all possibilities.