Executive summary

- Geoeconomics is a way of conceptualising the relationship between geopolitics and framing the policy issues that arise at the intersection of international economics and international security. It is also often defined more narrowly in terms of the application of specific economic policy instruments to achieve geopolitical aims.

- This report examines the potential and limits of geoeconomic statecraft in the context of the Australia-US alliance.

- A shift in alliance strategy towards China, from engagement to strategic rivalry and competition, has reframed international and domestic economic policy settings in light of the security concerns presented by China’s growing power and influence.

- China’s use of geoeconomic policy instruments has become a major concern for Australian policymakers. However, its use of economic statecraft has mostly been counter-productive in advancing its geopolitical interests.

- Australia and the United States have increased cooperation in some geoeconomic policy areas — most notably in relation to defence industry, technology and critical minerals — but geoeconomics remains an underdeveloped element of the alliance relationship, reflecting its foundations in a security treaty that is silent on economic issues.

- The new enhanced trilateral security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States (AUKUS) indicates that Washington recognises the importance of cooperation with allies in security as well as defence industry and technology.

- Like Canberra, Washington has struggled to recalibrate its economic engagement with Beijing to reflect changes in Chinese domestic politics and geopolitical realities and to reintegrate international economic, foreign and defence policymaking.

- The key analytical issue raised by geoeconomics is how to reconcile the positive-sum logic of the gains from international trade and the cross-border flow of goods, services, capital, people and ideas with the often zero-sum logic of strategic competition between nation states.

- One potential source of policy error is for policymakers to allow security concerns to trump or dominate economic considerations. Geoeconomics may serve as an excuse to substitute geopolitics for economics rather than balancing or reconciling the two perspectives.

- A number of Australia’s regional and extra-regional partners have recently identified economic coercion as an issue of concern, implicitly raising the threat of a collective response should China’s economic coercion continue or escalate. Australia and the United States should aim to capitalise on the concerns China’s use of geoeconomic statecraft raises for countries in the Indo-Pacific region.

- A multilateral approach to fostering resilience to China’s economic coercion should remain a paramount priority for both US and Australian policymakers.

- Australian policymakers should, therefore, engage the United States with the World Trade Organization reform process and encourage Washington to further invest in the international and regional trade promotion and trade defence architecture. Trade expansion and diversification among allies will ultimately better promote economic resilience than trade restrictions aimed at China.

Introduction

Nothing would better promote America’s geoeconomic agenda and strategic future than robust economic growth in the United States.1

…foreign trade enhances the potential military force of a country.2

International economic exchange is one of the most spectacularly successful examples of international influence in history; yet it is rarely so described. Why? Because routine, mundane, day-to-day economic exchange is often defined as either not involving power or not being ‘real’ foreign policy.3

Policy issues at the intersection of international security and international economics loom increasingly large for Australian and US policymakers. Geoeconomic statecraft is the use of economic policy instruments to further geopolitical, foreign policy and security objectives. A shift in alliance strategy towards China, from engagement to strategic rivalry and competition, has reframed international and domestic economic policy settings in light of the security concerns presented by China’s growing power and influence.

China’s use of geoeconomic policy instruments has become a major concern for Australian policymakers and a focus for Australian foreign policy. Recent bilateral meetings between Australian ministers and counterparts in Japan, Singapore, India, France, South Korea, New Zealand and the United States have all called out economic coercion as an issue of mutual concern. China’s restrictions on Australian exports during 2020 saw a reduction in exports, excluding iron ore, of 23 per cent, at a cost of between A$6.6 and A$12 billion in export earnings.4 These restrictions have been widely interpreted as economic punishment for foreign and other policy positions taken by the Australian Government. Australian producers have been able to recoup some of these losses in other markets, but it will take time to diversify away from the Chinese market.

A shift in alliance strategy towards China, from engagement to strategic rivalry and competition, has reframed international and domestic economic policy settings in light of the security concerns presented by China’s growing power and influence.

At the same time, the iron ore trade with China contributed to about half of the record trade surpluses Australia recorded in recent quarters. While iron ore and liquified natural gas (LNG) exports to China have not been affected, the measures taken by China to date highlight the potential for additional economic costs to be imposed. These costs are almost certainly intended as a signal to other countries, including US alliance partners, not just the Australian Government. However, China’s geoeconomic statecraft has mostly been ineffective in promoting its geopolitical interests.

Geoeconomic statecraft is not new, even if it has taken on new forms in the context of US-China rivalry. The Soviet Union broke off diplomatic relations and virtually all trade with Australia in response to the Petrov affair in 1954. Australian exports to the Soviet Union fell from A$52 million, or 3 per cent of merchandise exports, in 1953-54 to nothing by 1955-56 and did not recover their 1953-54 level until a decade later,5 but without changing Australian policy in the direction sought by the Soviets. Australia and the United States have often employed economic policy instruments, including economic sanctions, as part of their foreign policies.

The targeting of Australia by China raises new questions about how the United States and its allies might organise and implement a collective response. Joint statements on the issue of economic coercion have already implicitly raised the threat of a collective response on the part of the United States and its allies should that coercion continue or escalate. The Biden administration has said it will not “leave Australia alone on the field.”6 The United States, the European Union, Japan and the United Kingdom have joined as third parties to Australia’s World Trade Organization (WTO) case against China’s tariffs on Australian barley exports, although this is not unusual in the context of WTO litigation.7

Australia and the United States have increased cooperation in some geoeconomic-related policy areas, most notably on defence industry, technology and critical minerals. The new enhanced trilateral security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States (AUKUS) demonstrates that the United States recognises the importance of cooperation with its allies in these areas.8 Australia’s Prime Minister has called for an annual economic dialogue between Australia and the United States to complement the existing AUSMIN talks, with China’s economic coercion and reform of the multilateral trading system as agenda items.9 While Australia has sought to put geoeconomics issues onto the AUSMIN agenda, it is still an underdeveloped element in the alliance relationship. The 1951 ANZUS Treaty is silent on economic issues. The Australia-US Free Trade Agreement addresses bilateral trade and investment, but the United States has largely dealt itself out of the emerging Indo-Pacific regional trade architecture represented by the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

The Biden administration has linked any improvement in relations, including the removal of tariffs on Chinese imports, with China’s treatment of Australia, but China’s commitment to purchase US goods under President Trump’s ‘phase one’ trade deal continues to damage Australia’s interests. Domestic economic considerations increasingly inform US foreign policy, this concept is best encapsulated by the Biden administration’s ‘foreign policy for the middle class.’ In relation to trade policy, however, this would seem to be little different from President Trump’s ‘America First,’ with no immediate signs of change under Biden. The United States has enormous economic assets and potential it can bring to bear in its strategic competition with China, but an inward-looking administration will face major constraints in prosecuting a geoeconomic agenda.

The United States has enormous economic assets and potential it can bring to bear in its strategic competition with China, but an inward-looking administration will face major constraints in prosecuting a geoeconomic agenda.

My report explains the concept of geoeconomic statecraft and the evolution of geoeconomic thinking from classical political economy, through the Cold War and post-Cold War periods and in the more contemporary context of US-China strategic rivalry. It also seeks to draw lessons from that historical experience. An important lesson that emerges from this review is a tendency to underestimate US economic potential and overestimate the prospects for the relative decline of US economic power.

My report also examines a range of geoeconomic policy instruments, their use and effectiveness in the context of US-China rivalry. It then turns to examine the ways in which China and the United States have used geoeconomic statecraft and its implications for Australia. China’s use of geoeconomic policy instruments is unlikely to result in significant gains in geopolitical influence relative to its growing military power and may even undermine that influence. At the same time, the United States is unlikely to make full use of its enormous geoeconomic potential while it is recalibrating its international economic policy to new geopolitical and domestic realities. The report makes a number of recommendations in relation to both process and policy for the Australian Government in an alliance context. In particular, I argue that trade expansion and diversification among allies will better promote economic resilience and national security objectives than trade restrictions aimed at China.

What is geoeconomics?

Geoeconomics is a way of conceptualising the relationship between geopolitics and framing the policy issues that arise at the intersection of international economics and international security. It is also often defined more narrowly in terms of the application of specific economic policy instruments to achieve geopolitical aims. For example, Blackwill and Harris define geoeconomics as:

The use of economic instruments to promote and defend national interests, and to produce beneficial geopolitical results; and the effects of other nations’ economic actions on a country’s geopolitical goals.10

Even more succinctly, Luttwak famously defined it as “the logic of war in the grammar of commerce.”11 If statecraft is the “selection of means for the pursuit of foreign policy goals,”12 then geoeconomic statecraft can be viewed as the specific study and application of the economic means.

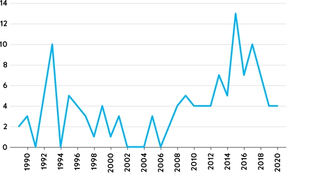

This report uses ‘geoeconomic statecraft’ synonymously with the more traditional ‘economic statecraft.’ ‘Geo’ in this context speaks to the intersection of geopolitics and economics. Geoeconomics is still something of a neologism. A search of the world’s leading English language news media since 1989 reveals that ‘geoeconomics’ and its variants has relatively little currency and does not show a clear trend in media mentions. While geoeconomic issues have become increasingly prominent, it would appear that popular discussion of these issues has yet to settle on geoeconomics either as a descriptor or a framework for analysis.

Figure 1. Number of media articles mentioning “geo(-)economic(s)”

The intersection of international economics and international security does not fall exclusively within any one discipline or field of study. Geoeconomics is often associated with the field or sub-discipline of international political economy (IPE). The modern field of IPE can trace its origins to Susan Strange’s observation in 1970 that international relations lacked economic analysis and economists were in turn often oblivious to considerations of politics.13 This observation came amid the economic turmoil associated with the progressive break-up of the Bretton Woods system of exchange rate determination in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Bretton Woods had been a key institution of the US-led post-Second World War liberal international order and its break-up had an impact on relations between the United States and its Atlantic alliance partners, as well as between the United States and the rest of the world. It would be difficult to understand transatlantic relations in this period without an understanding of the international financial system and its dynamics.

Yet appreciation of the intersection of international relations, the economy and economic policy pre-dates the 1970s. As Baldwin notes, “the generation of newly minted or recently converted international political economists that grew up in the 1970s was largely oblivious to the older tradition of international political economy.”14 The classical tradition in political economy has always been informed by an appreciation of these relationships. Geoeconomics infuses Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations in spirit, if not in name. While Smith is now best known for his critique of mercantilism, he also recognised that national security concerns often trump economic interests and that material welfare would sometimes need to be sacrificed to promote national security. Smith’s observation that “defence…is of much more importance than opulence,” is made specifically in defence of the navigation acts that restricted commerce as part of Anglo-Dutch strategic rivalry. Smith also understood the role of the institutions of state in promoting economic development and shaping domestic and international economic interactions. In contemporary parlance, Smith was a ‘state capacity libertarian.’15 As Blackwill and Harris observe, “for economic liberals such as Adam Smith…laissez-faire was but a form of geoeconomics; they differed from the mercantilists only on the tactics. For both camps, the question was how, not whether, to shape economic policies to serve state interests.”

Few economists would reject Smith’s conception of the relationship between the economy and the state and it is a strawman critique of economics to suggest that the discipline is blind to political or foreign policy considerations. If anything, the field of IPE has been even more economically reductionist in assuming that foreign relations are determined by domestic economic and commercial interests, particularly in its Marxist variants. Political economy and rational choice models, most notably game theory, have been applied to international relations and predicting international conflict with some success.16 Russett’s rational choice analysis of the Japanese decision to attack Pearl Harbor is one early example.17 More recently, Zhang uses a cost-benefit framework to analyse China’s use of military and non-military coercion in the South China Sea.18

The relationship between international trade and economic integration on the one hand and international peace on the other has long been of interest to social scientists. The liberal view that international trade should promote peace has been tested empirically with mixed results, although the weight of evidence points to a positive relationship, controlling for other factors. Mansfield found that the relationship between international trade and war is inverse and that freer trade produces positive security externalities.19 While there is evidence that increased bilateral trade flows reduce the risk of bilateral conflict, the evidence in relation to multilateral trade flows is more mixed, possibly because multilateral trade reduces mutual dependence in bilateral relations.20 Based on historical experience, the growth in US-China trade has likely reduced the probability of armed conflict between them.21 Trade also serves to increase the density of alliances, with countries that have high levels of trade with their allies less likely to be involved in conflict with both allied and non-allied countries.22 Allied countries are more likely to have strong bilateral trade relations, although this effect is stronger in bipolar rather than multipolar systems.23 International peace is also conducive to international trade, so causality potentially runs in both directions.

While there is evidence that increased bilateral trade flows reduce the risk of bilateral conflict, the evidence in relation to multilateral trade flows is more mixed, possibly because multilateral trade reduces mutual dependence in bilateral relations.

The existence of a hegemonic power like the United States is often viewed as conducive to the maintenance of an open international order. A hegemonic power that provides international public goods conducive to peace will also be supportive of free trade; although Mansfield found an ambiguous effect of hegemony on the level of global trade because freer trade itself does not meet the criteria of a collective good.24 The promotion of free trade and international economic integration was an important element of US foreign and international economic policy in the 1990s and early 2000s during the heyday of increasing globalisation and the United States’ unipolar moment.

But a hegemonic power like the United States may become less supportive of free trade when its power is challenged by an emerging rival like China. While there may be a positive feedback loop from increased trade to increased security, this process could run in reverse if international economic integration goes backwards due to shocks such as the financial crisis of 2008 or the global pandemic of 2020. The outbreak of conflict in 1914 after the first wave of globalisation in the 19th century is sometimes viewed as a knock-down argument against the liberal view that economic integration promotes peace, but this admittedly compelling historical episode is part of a much larger and more complex body of evidence, such as that considered by Mansfield, who jointly tests the role of trade in structural theories of international relations. As Mansfield shows, the relationship between trade and war is not independent of the structure of the international system and that structure has changed over time, most notably with China’s rise.

The key analytical issue raised by geoeconomics for policymakers is how to reconcile the positive-sum logic of the gains from international trade and the cross-border flow of goods, services, capital, people and ideas with the often zero-sum logic of strategic competition between nation states, although as Baldwin points out, power is not always a zero-sum game.25 Restraints on trade in the name of national security may increase security but at the expense of economic welfare, which is itself an important element of national power. While trade-offs are a familiar problem to economists, it is difficult to put a value on security that allows for a straightforward cost-benefit analysis. At one level, the value of security is infinite because security threats can be existential in nature. Existential threats could justifiably motivate significant economic sacrifice. The United States incurred significant resource costs in maintaining its security during the Cold War and successfully deterred a peer adversary throughout this period. In the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, the United States enjoyed a ‘peace dividend’ as it scaled back its military by around one-third in response to a reduction in the existential threat posed by the Soviet Union.

The guns and butter trade-off is a familiar one but becomes more complex when strategic competition occurs in domains other than purely military-diplomatic. Economic dependence can create security and other vulnerabilities nation states will seek to mitigate. As shown in previous USSC reports, globalisation has both a depth and breadth dimension.26 The breadth dimension helps diversify against security threats and other shocks that may arise from deeper economic integration.

Some view the effort to reintegrate China into the world economy, and WTO accession, in particular, as a strategic mistake by the United States, even though this has conferred large net economic benefits on the United States and helped maintain its economic leadership.

Strategic competition in the domain of technology and cyber security raises significant questions about how to regulate new technologies that have both economic and security implications. Technological leadership is difficult to preserve given that new ideas naturally diffuse and innovations can be copied, even in the absence of theft or espionage. Much of the transfer of non-military technology and ideas from the United States to China occurs legally and under license, from which the United States benefits economically. As Baldwin noted, the dramatically lower cost of moving ideas across borders has been a major driver of the most recent wave of globalisation.27

The only guarantee of technological leadership is continuous innovation. Policymakers that are overly focused on erecting barriers to the diffusion of technology and ideas to strategic rivals may find they have neglected policies to support their own innovativeness. US Government investment in defence-related research and development spending was undoubtedly an important element in its successful prosecution of the Cold War. However, the record of states successfully promoting indigenous innovation through policy interventions is poor relative to setting general policy frameworks that are supportive of bottom-up innovation by the private sector. China’s indigenous, state-led innovation strategy, formally under the rubric of Made in China 2025, may be less successful than the United States and its allies fear. As Gholz and Sapolsky argue, many of the ‘soft’ inputs into the US system of defence innovation are not easy for other countries to replicate.28 The advanced military equipment at the frontier of technology diffuses more slowly, both due to technological barriers to adoption,29 but also due to policy factors such as export control regimes that have slowed the technology diffusion that might otherwise be expected due to globalisation and lower barriers to the transmission of ideas.

Balancing economic and security considerations is made more difficult by strategic uncertainty. One potential source of policy error is for policymakers to allow security concerns to trump or dominate economic considerations. Geoeconomic concepts, poorly applied, may serve as a pretext to substitute geopolitics for economics rather than balancing or reconciling the two. Reverting to a national security mindset avoids having to wrestle with difficult trade-offs.

However, risks run in the other direction as well. Some view the effort to reintegrate China into the world economy, and WTO accession, in particular, as a strategic mistake by the United States, even though this has conferred large net economic benefits on the United States and helped maintain its economic leadership.30 For example, an ‘offensive realist’ like Mearsheimer argued as early as 2001 that a wealthy China would not be a status quo power and it is therefore in the interests of the United States to retard its economic growth.31 However, the plausible counterfactuals to the economic and political engagement policies pursued previously by the United States, Australia and others would not necessarily have left the United States and its allies better off either economically or strategically.32

Balancing economic welfare and national security demands that economic and security policy are mutually informed by a multi-disciplinary perspective. This has significant implications for the organisation and development of public policy, as we shall see later in this report.

Geoeconomic thinking in the Cold War and post-Cold War period

The size of an economy has always been viewed as a critical element of national power and economic policy has long been used as an instrument of foreign policy. The dominant role of the United States in global politics in the post-Second World War period is in large part due to the size and dynamism of its economy relative to that of other major powers. The post-war international political and economic order led by the United States was a direct response to a pre-war conception of mercantilist trade and beggar-thy-neighbour economic policy that was seen as having sown the seeds for military conflict. In earlier eras, mercantilist doctrines informed foreign and security policy, with both embodying a zero-sum logic. The United States sought to promote a post-war international order built around a system of security alliances, but also an open international trading system that would support the economic development of the United States and its allies to counter the appeal of communism. US Secretary of State George Marshall declared in 1947 that “the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace.”33

According to Baldwin, “the American use of trade policy to construct an international economic order based on nondiscriminatory trade liberalisation in the period after the Second World War was one of the most successful influence attempts using economic policy instruments ever undertaken.”34 Trade expansion can be a geoeconomic tool, just as much as trade restriction. One element of the post-war international order was trade and economic discrimination against communist countries as outsiders to that order, a position that still holds for Cuba and North Korea. The GATT and then the WTO upheld the principle of non-discrimination, maintained prohibitions on import and export controls, and regulated the use of trade defence measures such as anti-dumping duties, although those trade agreements also included national security exceptions. The WTO serves as a discipline on the use of some geoeconomic policy instruments and offers some protection against discriminatory trade practices, especially for small open economies like Australia, but does not entirely preclude them either.

The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union between 1945 and 1991 was largely defined in terms of military, political and ideological competition. Yet the Soviet Union was also seen as a serious economic competitor in the 1950s and 1960s, with some leading US economists and analysts predicting that the Soviets’ command economy would eventually overtake the United States in living standards. Successive editions of leading American economics textbooks published between 1960 and 1980 demonstrate both over-confidence in the potential for Soviet growth and an asymmetric response to past forecast errors.35 However, from the 1970s onwards, it became increasingly apparent that the Soviet Union could not compete with the United States in the economic domain. This in turn constrained its ability to compete on technology and military superiority. Central planning crushed both the economic and technological dynamism of the Soviet Union and its client states.

With the end of the Cold War and the unipolar moment of a dominant United States, there was an expectation that conflict between states would increasingly manifest in the economic domain given the inability of other powers to directly challenge the United States militarily. Luttwak’s seminal 1990 article in The National Interest claimed that “as the relevance of military threats and military alliances wanes, geoeconomic priorities and modalities are becoming dominant in state action...in the new geoeconomic era not only the causes but also the instruments of conflict must be economic” (emphasis in original).36 Similarly, Samuel Huntington argued in 1993 that “in the coming years, the principal conflicts of interests involving the United States and the major powers are likely to be over economic issues. US economic primacy is now being challenged by Japan and is likely to be challenged in the future by Europe.”37

Even as the United States came to dominate the world economy and geopolitics, questions were raised about the economic foundations of US dominance. Paul Kennedy’s 1987 historical survey The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 highlighted “differentials in growth rates and technology change, leading to shifts in the global economic balances, which in turn gradually impinge upon the political and military balances.”38 Kennedy’s work was widely read as a warning from history about the dangers of US global influence overreaching its economic base. According to Kennedy, “the task facing American statesmen over the next decades, therefore, is to recognize that broad trends are under way, and that there is a need to ‘manage’ affairs so that the relative erosion of the United States’ position takes place slowly and smoothly.”39 Kennedy is soon to release an updated edition of this work.

Luttwak’s conception of geoeconomic competition led to a book published in 1993, with the self-explanatory title, Endangered American Dream: How to Stop the United States from Becoming a Third-World Country and How to Win the Geo-Economic Struggle for Industrial Supremacy.40 Some see the book as prophetic in relation to the more contemporary strategic competition between China and the United States. However, it was a poor predictor of US prospects in the 1990s, 2000s and even today, where the United States remains at the frontier of global economic growth, livings standards, productivity and innovation. Luttwak’s contribution was part of a late 1980s and early 1990s genre predicting US decline relative to Japan in particular. Japan’s strategic industry and trade policy was assumed to lead to Japan’s economic ascendency, eclipsing the US economy, which would, in turn, impel the United States and Japan into military conflict.41

Subsequent events were not kind to this analysis. Japan’s economy stagnated, in part because of the very strategic industry and trade policies that were meant to lead to its economic ascendency, but also because demographic trends meant that Japan began to contract in terms of the absolute size of its population, although average living standards fared better. As a democracy and ally of the United States, the notion that Japan and the United States would inevitably come to blows due to competing economic interests seems even more mistaken. It assumed mercantilist considerations would trump a more fundamental alignment of economic and other interests. American policymakers have, if anything, spent much of the last three decades encouraging Japan to get its economic house in order to support growth in the world and US economy.

In each of the cases of the Soviet Union, Japan and Europe, it was assumed that their greater subordination of the economy to the interests of the state and the logic of state power and strategic competition would lead to a decline in overall US power in relative terms, even if the United States remained competitive in the military domain.

The United States was also expected to decline in power relative to the European Union. The EU’s project to create a common currency was driven primarily by geopolitical rather than narrowly economic considerations, a textbook application of notions of geoeconomic statecraft. The euro project was part of a broader effort to bind Europe together in a way that would prevent the military conflicts of the past. The euro embodied the liberal logic that international economic cooperation would foster international peace, although overlooked the liberal case for greater, not less, flexibility in exchange rates. It was also assumed that a common market and common currency would give Europe a greater collective weight in international politics.

Again, subsequent developments were not kind to these expectations. The use of a common currency to drive political unification ultimately led to both economic stagnation and intra-European political conflict. As I document in my United States Studies Centre (USSC) publication, The “reserve currency” myth: The US dollar’s current and future role in the world economy, the euro’s role in the world economy has declined, partly due to the common currency locking Europe into a sub-optimal monetary policy regime.42 The failed euro project highlights some of the dangers of prioritising geopolitics over economics.

This brief history of analyses based in geoeconomic concepts and related ideas should sound a cautionary note about their future application. In each of the cases of the Soviet Union, Japan and Europe, it was assumed that their greater subordination of the economy to the interests of the state and the logic of state power and strategic competition would lead to a decline in overall US power in relative terms, even if the United States remained competitive in the military domain. In each case, the economic dynamism of the US economy ensured that US power did not decline in either absolute or relative terms. Of course, these failed predictions do not necessarily invalidate geoeconomics as an analytical framework or a potentially useful set of policy instruments. Useful frameworks can sometimes be badly applied. But the geoeconomic basis for the relative decline of US national power was never well-founded.

Geoeconomics and the rise of China

More recently, the rise of China and US-China strategic rivalry has sparked renewed interest in geoeconomic conceptions of great power competition. China’s economic reforms of the late 1970s saw a rapid expansion in its economy. While China remains a poor country in terms of average living standards, its economy is set to equal if not surpass that of the United States in absolute size. As with the United States historically, with growing economic heft comes the increased ability to project military power and geopolitical influence. China is still not in a position to directly challenge the United States militarily with any certainty of success. However, strategic competition with the United States has also manifested in the economic domain. China has sought to extend its international economic influence and has increasingly come to employ economic policy instruments, inducements and coercion as an increasingly integrated part of its foreign policy toolkit.

The increased interest in geoeconomics as a lens for US-China relations and strategic competition also reflects important changes in China’s internal politics. In the reform period from 1978 until the ascendency of Xi Jinping in 2012, China liberalised its economy and reintegrated itself into the world economy, including accession to the WTO in 2001. China continues to selectively liberalise international access to its capital markets, including as an integral part of the ‘phase one’ trade deal with the Trump administration, although the financial sector is also increasingly being harnessed to service the economic development priorities of the Chinese party-state.43 China’s economic liberalisation has been widely hailed as the single greatest poverty reduction initiative in human history and has benefited the world and US economy, although has also had important distributional consequences that have affected national politics outside China.

The globalisation and integration of the world economy in the post-Cold War period increased economic interdependence in ways that cut across state sovereignty, although without necessarily undermining the power of the state. Governments retained substantial roles in domestic economic affairs, even as developments in the global economy impinged on national economic policy. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, however, globalisation, and with it, global productivity, has slowed or stagnated, as discussed in an earlier report.44 The 2020 global pandemic has been another blow to globalisation. The loss of economic dynamism correlates with the rise of populist politics domestically, not least in the United States, which has the potential to spill over into the conduct of international economic policy, giving rise to a negative feedback loop.45 To the extent that there is a positive relationship between global economic integration and international peace, then the stagnation or reversal of the trend to greater economic integration makes conflict more likely.

It was widely hoped, although not necessarily assumed or taken for granted by US and Australian policymakers, that economic liberalisation would promote greater political liberalisation and a less belligerent China, at least relative to its past. While these impulses were at least somewhat in evidence within China in the early to mid-2000s, with the Xi ascendency from 2012, China’s domestic politics and economic policy went in the other direction. Tentative liberal economic and political impulses were crushed with renewed force by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The CCP increasingly came to reprioritise state control over liberalisation and economic growth. Whereas the party-state previously sought to divest itself of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), it has since re-embraced them. China has also renewed its interest in strategic industry and trade policy, including an ambitious program to become self-sufficient in the production of key technologies, a program informed not just by economic development priorities, but also strategic and military imperatives or civil-military fusion. Its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to build trade-related infrastructure abroad is also heavily motivated by geopolitical considerations, including resource and trade security.

The CCP’s growing project of state control motivated by both internal politics and foreign policy objectives has intensified strategic competition with the United States and its allies. The attempt to engage China and draw it into the US-led liberal international order prior to 2012 has given way to a more defensive posture as the United States and its allies recalibrate their perceptions of China’s intentions, capabilities and policies. Part of this more defensive posture includes recognising China’s growing use of economic instruments as tools of foreign and security policy and geopolitical power projection. This in turn has prompted the United States and its allies to re-think the relationship between their economic policies and other instruments of state power. In particular, there is concern that the greater separation between the economic and political domains within Western democracies may put them at a disadvantage in strategic competition with China.

Widely held assumptions about relative US decline with respect to China may turn out to be misplaced, as they were in relation to the Soviet Union, Japan and Europe. At the very least, we should interrogate the assumptions underpinning these earlier failed predictions based on geoeconomic thinking.

Yet the history of geoeconomic ideas briefly reviewed here also cautions against assuming that the Chinese model better positions it as a geopolitical rival. In 1999, Gerald Segal famously posed the question ‘Does China matter?’ pointing to its many systemic political and economic weaknesses.46 Many of his observations, including the fact that China has few friends or allies in the international system, remain pertinent today, even though few would now disagree that China matters a great deal. What some see as Chinese geopolitical and geoeconomic strengths, others argue are evidence of weakness.47 China exhibits with a lag many of the weaknesses seen in Japan, including population ageing and the near-term prospect of an outright decline in its population. While the United States also faces the prospect of demographic stagnation, its demographics are still more favourable than that of China.48

China may prove to be less of a geopolitical challenger than feared and its use of geoeconomic statecraft may turn out to have ambiguous implications for its prospects as a rival to the United States. In particular, it is likely to provoke defensive reactions that render geoeconomic statecraft less effective in promoting Chinese interests.49 As Luttwak notes, adapting his older arguments about Japan, as “China’s continuing rise ultimately threatens the very independence of its neighbours, and even of its present peers, it will inevitably be resisted by geoeconomic means— that is, by strategically motivated as opposed to merely protectionist trade barriers, investment prohibitions, more extensive technology denials, and even restrictions on raw material exports to China if its misconduct can provide a sufficient excuse for that almost warlike act.”50 Almost all of these measures have already been implemented to at least some degree by the United States, Australia and other allied countries.

Widely held assumptions about relative US decline with respect to China may turn out to be misplaced, as they were in relation to the Soviet Union, Japan and Europe. At the very least, we should interrogate the assumptions underpinning these earlier failed predictions based on geoeconomic thinking. Without understanding how this thinking failed in the past, it will be difficult to successfully recalibrate geoeconomic statecraft to meet the current and prospective strategic challenges posed by China. At the same time, we should adapt the lessons from successful episodes of economic statecraft in the past to current US-China rivalry.

Geoeconomic policy instruments: Their use and limitations

Almost any instrument of economic policy can potentially be adapted to foreign policy objectives, so the list of potential geoeconomic policy instruments is essentially open-ended. Economic policy instruments can also have geopolitical implications even if they are not employed with geopolitical objectives in mind. For example, the dominant role of the US dollar in the world economy means that changes in US monetary policy affect the global economy. These international spillovers can, at the margin, destabilise emerging market economies and promote domestic political instability, which in turn may have geopolitical implications. Yet the US Federal Reserve has an exclusively domestic focus when it sets policy, reflecting its statutory mandate.

The role of the US dollar in the world economy is not only a major source of US economic strength, but also geopolitical influence, but that role reflects economic fundamentals rather than an explicit attempt to wield geopolitical influence through exchange rate policy. The role of the US dollar makes US economic sanctions particularly effective. I discuss the geoeconomic role and implications of the US dollar in my USSC report, The “reserve currency” myth.51 In particular, I discuss why it is difficult for both the United States and China to ‘weaponise’ monetary and exchange rate policy for geopolitical purposes.

Because geoeconomic tools are routinely used for non-geoeconomic ends, it can be difficult to establish when they are being used with foreign policy objectives in mind. This ambiguity can be useful when states want to apply economic pressure but maintain some level of plausible deniability for diplomatic purposes or for the purposes of avoiding scrutiny from the WTO or similar bodies. For example, China’s specific use of geoeconomic policy instruments against Australia is not usually directly linked at an official level by China to Australian foreign policy, but China has made its dissatisfaction with Australian policy positions known through both official and unofficial channels. Economic intimidation is often cloaked in formal legal and regulatory requirements where the CCP enjoys considerable discretion. The fact that China seeks to maintain a semblance of conformity to international rules and norms and avoid international scrutiny by the likes of the WTO implies that these norms and institutions still retain some force and influence over Chinese policymakers.

The fact that China seeks to maintain a semblance of conformity to international rules and norms and avoid international scrutiny by the likes of the WTO implies that these norms and institutions still retain some force and influence over Chinese policymakers.

Economic warfare is sometimes pursued as an element of open military conflict. While the economic dimension of such conflicts is obviously important as part of the overall war effort and may even determine the outcome, economic policy in this context is as a complement to, rather than a substitute for, other instruments of conflict. Mercantilist economic ideas can also serve as a motivation for military conflict, although in this case, the instruments of military power are used to pursue economic objectives rather than the other way around.

There are also important issues around the suitability and efficacy of economic policy instruments for pursuing foreign policy and security objectives. There is a longstanding debate in the international relations and IPE literature around the effectiveness of economic sanctions as a foreign policy tool. Sanctions are often criticised as being ineffective, particularly where they have not changed behaviour on the part of target countries. This in turn has often been taken as an example of broader limits on the scope and potential of geoeconomic statecraft. However, a broader reading, as suggested by David Baldwin, shows that sanctions may be effective in sending signals or imposing costs on other actors. Sanctions may also be less costly than alternatives such as going to war.52 Sanctions on Iran, for example, may not succeed in realising US and European objectives in relation to its nuclear program but are likely to be less costly than military action, regardless of their effectiveness. The effectiveness of geoeconomics instruments needs to be evaluated in a specific strategic context and relative to alternative policies.

Trade policy instruments, such as tariffs, quotas, anti-dumping and countervailing duties and subsidies can all be used for geoeconomic as well as domestic economic and political purposes. Because the gains from trade are mutual, restrictions on trade are likely to be costly to both sides. These costs are the reason why multilateral trade rules and trade agreements seek to restrain their use. However, foreign policy and security considerations may outweigh consideration of economic cost. China’s recent restrictions on imports from Australia has likely harmed Chinese producers and consumers whose interests have been sacrificed to China’s foreign policy objectives. These costs are still a discipline on China’s use of geoeconomics instruments. A partial or complete embargo on Australian iron ore or LNG exports, for example, while potentially very costly to Australia, would also impose potentially prohibitive costs on China given its dependence on Australian exports and because Australia is at the bottom of the global cost curve for many commodities, including iron ore.

Controls over inbound and outbound foreign investment are another geoeconomic policy tool. Both Australia and the United States have recalibrated their screening of foreign investment in response to China’s increased profile in inbound Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in both countries in an effort to balance the economic benefits of FDI and security concerns, a topic of an earlier USSC report.53 Yet China has also tightened its scrutiny of outbound FDI as it increasingly focuses on its domestic economic development agenda relative to its former ‘going out’ policies. Its overseas investment outflows in 2020 declined to their lowest since 2016.54 It is difficult to discern the impact of national security-related foreign investment controls on cross-border capital flows relative to the impact of general de-globalisation shocks such as the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic.55

Foreign aid is often pursued for foreign policy as well as economic development motivations. For example, Australia’s aid to the South Pacific, while aimed at promoting economic development, is also intended to secure the region against influence from external powers such as China. It is not surprising China views its official development assistance the same way.

Foreign aid and development assistance from Australia, the United States and multilateral development banks has a very mixed record at promoting economic development and may have also fostered local corruption in recipient countries that potentially makes them even more vulnerable to foreign influence.56 In competing with China for geopolitical influence via foreign aid and official development assistance, Australia and the United States should focus on institution building that is more resistant to corruption. US and Australian influence within multilateral development banks (MDBs) could also be better harnessed to counter China’s Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) and BRI. MDBs could as much as triple their lending capacity by reforming their prudential and liquidity standards, which would assist in closing infrastructure gaps in the Indo-Pacific.57

Critical goods and commodities

Critical goods and commodities have emerged as a key concern of Australian and US policymakers, especially since China’s imposition of export controls on rare earth exports to Japan in 2010, although the motivation for those controls likely reflected a mix of domestic and foreign policy objectives. Critical minerals have been one area of focus and cooperation for the United States and Australia, as discussed in an earlier USSC report.58 There is a case to be made for market failure in the market for critical minerals that warrants intervention to diversify and secure supply. However, as Gholz and Hughes show, Japan was able to adjust despite the dominance of Chinese producers and Japan’s apparent vulnerability as a key downstream consumer of rare earths. These longer-term dynamic adjustments suggest the scope to use critical commodities as geoeconomic policy instruments is more limited than conventionally assumed.59

Fuel security has also been a focus for Australian policymakers, leading to government subsidies to local fuel refiners to help maintain security of supply. Many concerns over security of supply for critical goods and commodities can be addressed through stockpiling, such as the US Government’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve, rather than other, potentially more distortionary, forms of government intervention, such as production subsidies.

Supply chain security has emerged as another issue in the wake of the global pandemic and intersects with long-standing issues around domestic industry policy. The shortages that emerged during the pandemic were for the most part due to big demand shifts that no supply chain configuration could reasonably be expected to accommodate. Global supply chains pivoted very quickly to address these shortages, largely led by the price mechanism. The evidence suggests that the loss in output during the pandemic would have been even more severe if global supply chains had been nationalised.60 The Australian Government’s preference for locally produced vaccines during 2020 led to vaccine shortages in the face of the delta variant outbreak in 2021, inducing lockdowns with significant economic costs while the government sought new supplies from overseas. This is a very good example of how economic interdependence can reduce vulnerability to shocks, while domestically focused industry policy can increase it.

The pandemic and China’s emergence as a key supplier of critical goods and commodities has prompted both the United States and Australia to review supply chain security and related vulnerabilities. However, the combined industrial capacity of the United States and its allies far exceeds that of China. Rather than reshoring production, the focus on these efforts should be on ‘ally-shoring,’ developing robust supply chains among trusted partners. The Productivity Commission has found that Australia’s import and export market concentrations do not pose significant vulnerabilities and are readily manageable by business without having to embrace more interventionist industry policy.61 For its part, the Biden administration’s 100-day supply chain review was notable mainly for its minimal consideration of the potential for cooperation with allies on supply chain security.62 There is a danger that domestic economic imperatives come to dominate the supply chain security agenda in the United States at the expense of effective cooperation with allies.

There is a role for industry policy in meeting specific defence needs. The Australian Government’s initiative to build a local munitions production capability is one example.63 However, too often, defence priorities are skewed by domestic industry and employment objectives. The now-abandoned Collins-class submarine replacement project, effectively became a substitute for the South Australian car industry, to the detriment of both cost and delivery timetable, potentially leaving a significant capability gap in Australia’s force posture.64 It remains to be seen to what extent the replacement nuclear submarine project with the United States and the United Kingdom avoids some of these pitfalls. US industry policy is discussed in more detail below.

The potential for capture by domestic economic and political interests pursuing a parochial agenda is a substantial risk to the successful development and prosecution of an agenda for geoeconomic statecraft, as suggested by the historical record in relation to US R&D.65 Even in the area of critical minerals, domestic interests in the United States have sought to undermine Australian-US cooperation.66 Both Australia and the United States will need to work to ensure that domestic policy processes are focused on genuine vulnerabilities and not sidetracked by these interests. Policymakers also need to be wary of the ‘strategic goods fallacy.’ No good is inherently strategic, it only becomes so in a specific geopolitical context.67 By focusing on goods deemed to be strategic, policymakers may lose sight of that context.

Bilateral, plurilateral and multilateral trade agreements are also important geoeconomic policy instruments, not just as a means of promoting increased trade and greater economic integration. Both the United States and Australia have historically promoted the multilateral trading system as a key element of the US-led global liberal order. As a small open economy, the multilateral trading rules under the WTO help protect Australia against economic discrimination and coercion, even if WTO processes are protracted, offering little immediate relief.

As a small open economy, the multilateral trading rules under the WTO help protect Australia against economic discrimination and coercion, even if WTO processes are protracted, offering little immediate relief.

Apart from their static economic benefits, a key dynamic benefit from trade agreements is market access insurance and their potential in restraining the outbreak of trade wars, a point that was often overlooked in the debate over the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement, which focused too heavily on static economic benefits.68 Australia is currently using the WTO’s dispute resolution mechanisms to address China’s use of trade measures against Australia. Australia has a strong interest in keeping the United States engaged in both the multilateral trading system and regional trade agreements at a time when US politicians and policymakers have lost sight of their value. One way to secure greater US engagement with this trade architecture is to highlight its value in promoting US interests in its geopolitical competition with China. Trade agreements are potentially an effective but underutilised mechanism in promoting allied supply chain security, yet US domestic political opposition to trade agreements remains high.

How effective is China’s geoeconomic statecraft?

Some analysts have claimed that China is the world’s leading practitioner of geoeconomic statecraft and ‘at a maestro level.’69 China’s overseas investments, pursuit of bilateral and regional trade agreements, foreign aid and its BRI are often viewed as being fused as part of an overall geoeconomic strategy aimed at securing its access to vital economic inputs, increasing economic dependence on China and expanding its geopolitical influence. China has increasingly shown a willingness to subordinate its economic interests to promote geopolitical and foreign policy objectives, just as it has prioritised party-political control over domestic economic growth. This is a departure from the previous prioritisation of economic growth seen in the reform era from 1978 onwards.

However, its use of geoeconomic policy instruments may also reflect constraints on its ability to pursue its objectives through military, diplomatic and other policy instruments. In particular, its lack of allies in the international system constrains its ability to work cooperatively with other countries to promote its interests. In this context, the use of geoeconomic statecraft can be taken as a sign of weakness rather than strength. The Belt and Road Initiative was conceived when the Chinese state was in a state of crisis in 2012-13 and was in part a response to the then US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership.70 While BRI-related investments are often cited in the trillions, total FDI by China in BRI countries from 2013 to 2020 was only US$136 billion,71 although these data may not capture the full extent of the initiative.

As a tool for promoting China’s geopolitical interests, China’s use of geoeconomics has a mixed track record of success. Blackwill and Harris maintain the ‘body of evidence’ points to success, but also concede that “geoeconomic success is sometimes exaggerated, including with respect to China.”72 Success is very much dependent on strategic context. China’s geoeconomic influence is arguably greater with respect to smaller, poorer and more corrupt countries than it is with respect to developed countries like Australia. China’s use of geoeconomics is of a larger concern in the Indo-Pacific region than within an Australia-US alliance context.

It is difficult to systematically evaluate how successful China’s use of geoeconomic statecraft has been. In some cases, it has been counterproductive, not least in eliciting countervailing responses from affected countries, as well as the United States and its allies.73 Examples often given as successes include the Norwegian Nobel Prize dispute 2010-16, the Philippines maritime dispute 2012-16, South Korea’s THAAD missile system deployment, and Mongolia’s Dalai Lama visit in 2016.74 In each case, the targeted country offered up concessions to China, but these concessions need to be interpreted in a broader strategic context. None of these episodes in themselves would seem to represent major geopolitical gains, although collectively they can be seen as an expansion of China’s influence, even in the presence of countervailing responses.

China’s export controls on rare earth exports to Japan in 2010 encouraged other countries to develop alternative sources of supply and motivated Australian-US cooperation in securing supply. China lost a WTO case over the issue, with which it ultimately complied, highlighting the value of the WTO in disciplining the use of export controls for geopolitical objectives. Yet China has subsequently threatened to use its control over rare earths in prosecuting its foreign policy agenda, suggesting it still sees value in threatening their use.75

China’s enormous demand for commodities is a source of geopolitical leverage, but its dependence on overseas supplies is also a strategic vulnerability. Chinese FDI abroad and its BRI can both be viewed as efforts to promote security of supply to address this vulnerability. Similarly, China’s overseas investments, including FDI in Australia, can be viewed as instruments for promoting resource security and geopolitical influence, but they also leave China’s overseas assets vulnerable to expropriation in the event of a conflict. Such mutual vulnerability helps discipline Chinese behaviour.

China’s geoeconomic statecraft with respect to Australia has mostly been counterproductive. Australian public opinion has swung dramatically against China and Australian cooperation with the United States has strengthened not weakened.

The campaign to internationalise the renminbi was widely interpreted as an effort to promote China on the world stage, but in the end amounted to little more than a vanity project.76 Internationalisation was also seen as a way of promoting domestic financial liberalisation and reform, but these efforts were halted when financial volatility offended the CCP’s desire for predictability and order. International use of the renminbi has stagnated since 2015.77 In this case, domestic politics trumped both economics and geoeconomic statecraft, leaving China with no more geopolitical influence than before.

Australia serves as the latest and most prominent test case for China’s use of geoeconomic statecraft. Zack Cooper and his co-authors claim that China’s economic coercion “presents the Australia-US alliance with its greatest challenge in decades.”78 But this is overstating the problem, not least relative to the hard power challenge China poses to the ANZUS alliance. The economic damage referenced in the introduction to this report is for the most part manageable. It has also prompted Australian producers to diversify their markets while imposing costs on Chinese producers and consumers. The long-run dynamic responses highlighted by Gholz and Hughes in the case of rare earths point to the use of geoeconomics policy instruments undermining rather than enhancing China’s long-run geopolitical influence.

China’s intention is not so much to inflict significant economic damage but to send a signal of disapproval to Australian policymakers and policymakers in other countries. How that signal is interpreted largely determines its success in promoting China’s interests. Many countries, including Australia, will come to view China as a less reliable actor and strengthen their cooperation with the United States while diversifying their economic relationships.

China’s geoeconomic statecraft with respect to Australia has mostly been counterproductive. Australian public opinion has swung dramatically against China79 and Australian cooperation with the United States has strengthened not weakened. This does not mean that China will not continue to use geoeconomic policy instruments in an intimidatory or coercive manner. China could expand its measures to include other commodities, including iron ore and LNG, increasing economic costs for both Australia and China, even if these actions are counterproductive. Far from being a maestro at geoeconomic statecraft, China may find that its geopolitical influence has diminished rather than increased because of its overuse of geoeconomic instruments. As a recent comprehensive RAND study of Chinese influence concluded, “China faces a dilemma in exercising influence: The more strongly China tries to use its clout to force outcomes in other countries, the greater the backlash it foments and the more those countries reject its influence.”80

How effective is US geoeconomic statecraft?

We have seen how geoeconomic statecraft was embedded in US foreign policy both during and after the Cold War. More recently, some scholars have claimed that the United States has suffered a “large-scale failure of collective strategic memory” in relation to geoeconomics. Blackwill and Harris maintained in 2016 that the “United States has no coherent policies to deal with these Chinese geoeconomic actions.”81 This was something of an overstatement at the time. Since then, geoeconomics and industrial policy have featured much more prominently in US national security strategy. The United States also makes extensive use of coercive economic measures in support of foreign policy and security objectives.82 It is fairer to say that the growing awareness of US policymakers of the economic dimension to geopolitical and strategic competition with China, reflected in the transition from the 2015 to 2017 National Security Strategy, has not been matched by collective policy responses from the United States and allies. Like Australia, the United States has struggled to recalibrate its economic engagement with China to reflect changing Chinese domestic politics and geopolitical realities and to reintegrate international economic and foreign policymaking. Domestic economic priorities have given the United States an inward focus that will make it harder for the Biden administration to promote a geoeconomics agenda that works cooperatively with allies.

The failure of the United States to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership and its inability to progress a transatlantic trade agreement are widely acknowledged as failures of both economic policy as well as geoeconomic statecraft. These failures straddle the Obama, Trump and Biden administrations.

The failure of the United States to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership and its inability to progress a transatlantic trade agreement are widely acknowledged as failures of both economic policy as well as geoeconomic statecraft. These failures straddle the Obama, Trump and Biden administrations. The Trump administration’s approach to China also exemplifies the problem. Trump took a zero-sum view of the economic relationship between the United States and China, yet ironically sought a trade deal that would bind the two economies more closely together. The Trump Administration oscillated between decoupling and locking the United States and Chinese economies into a managed trade deal that increased the dependence of American producers on China. Trump’s embrace of tariffs as a geoeconomic tool was economically counterproductive, costing hundreds of thousands of US jobs while undermining the US and world economy. While it may have focused the attention of Chinese policymakers on US concerns and extracted some concessions in the context of the ‘phase one’ trade deal, particularly on intellectual property protection, these ‘concessions’ were as much in China’s self-interest as they were in US interests.

The phase one trade deal also directly undermined US allies like Australia by promoting trade diversion to US producers.83 China’s actions against Australian barley and coal exports have helped it to meet its purchasing commitments under the deal. China’s economic measures against Australia have thus served its objectives in two ways: punishing Australia while providing concessions to the United States. The Biden administration has left the Trump administration’s tariffs in place and shows little sign of prioritising trade negotiations, having let the Congressional Trade Promotion Authority lapse. US disengagement from the evolving Indo-Pacific regional trade architecture in the form of CPTPP and RCEP represents a major challenge for Australian policymakers looking to the United States to balance China’s economic role in the region.

The United States has a mixed track record of supporting allies in response to China’s economic coercion. South Korea was left to fend for itself when it faced Chinese economic coercion over the THAAD missile deployment, pointing to an underdeveloped US policy framework for addressing such coercion in conjunction with allies. This highlights the extent to which the success of China’s geoeconomic statecraft depends not so much on the instruments it employs, but the allied response. If China makes few geopolitical gains on the back of its economic coercion and the United States and allies can successfully diversify and secure their economic relationships through the alliance network, then China’s economic statecraft will have been substantially neutralised. This would be an effective defensive application of geoeconomic instruments built on trade expansion rather than restriction.

There is also a danger that the US pursuit of geoeconomic statecraft undermines the institutions and norms of the rules-based order. As Blackwill and Harris concede:

upholding the rules-based system still remains the best strategy for maximizing present U.S. geopolitical objectives, and perhaps policy makers have further determined that the United States would be better off with a strategy that did not make [geoeconomic] insight manifest. After all, the United States still supplies far more global public goods than any other country, including policing of the global commons; the rules-based system is in many ways meant to ease the cost of those tasks, and so the United States has more to lose if that system collapses on itself.84

The Obama and Trump administrations undermined the dispute resolution function of the WTO in a way that damaged the rule of law in international trade, even going so far as to consider withdrawal and supporting Russia in its WTO action against Ukraine in an effort to preserve its national security prerogatives under international trade law. The Republican Party shows every sign of having given up on the WTO, wanting to return to the pre-WTO system of non-binding dispute resolution. As a small open economy potentially vulnerable to economic coercion, a major priority for Australian policymakers should be to engage the United States with the WTO reform process and continue to invest in the international trade promotion and trade defence architecture.

US industrial policy

There is a widely held view among US policymakers that the US industrial base has been allowed to deteriorate in a way that puts the United States at a disadvantage in strategic competition with China. The United States and some US allies have turned to a number of industrial policy initiatives to address this perceived disadvantage.85 Weiss suggests the United States suffers from “a seriously depleted industrial ecosystem,” referencing the decline in US manufacturing employment and the manufacturing share of GDP.86 But both these metrics are symptomatic of economic and national security strength, not weakness. The decline in both metrics are stylised facts of both productivity growth and economic development, not economic weakness or relative decline.

The US Innovation and Competition Act of 2021 represents a major overhaul of US industrial policy and a significant change in the US Government’s role in the US economy that is explicitly aimed at countering Chinese influence at home and abroad. Yet the legislation is also full of provisions aimed at servicing domestic economic redistribution and diversity objectives that highlight how easily strategic industry policy can be diverted from its ostensible objectives. As Krueger notes, “although these provisions may well achieve their objectives for regional development and diversity, they are unlikely to strengthen America’s manufacturing and defence capabilities.”87

As Lincicome shows, the US manufacturing sector, particularly those elements related to defence, is in rude health, not least relative to China.88 The United States continues to lead the world in manufacturing output, exports and investment. Foreign direct investment in US manufacturing exceeds total FDI inflows into China. According to Lincicome, “the industries that are most closely tied to national security — including those now prioritised due to COVID-19 — have not experienced significant historical declines and in most cases have expanded.”89 As Gholz and Sapolsky point out, US defence-related R&D “is about two-thirds of what all other countries in the world, American friend or foe, spend.” The US defence-related innovation system also benefits from ‘soft’ inputs, such as domestic institutions and an innovation culture, that are difficult if not impossible for other countries to replicate.90

The global shortage of semiconductors due to pandemic-related shifts in demand and China’s drive to promote indigenous production and self-sufficiency has focused attention on this sector in particular. The United States remains a technological leader as well as the leading producer of semiconductors. For now, China remains dependent on Taiwan and Japan for its supply of semiconductors and this is a source of vulnerability for China that could potentially be exploited as part of a collective response to Chinese economic coercion. But US sanctions targeting the Chinese semiconductor industry as part of the emerging US-China tech war have had the unintended effect of forcing Chinese firms to more fully embrace the Chinese Government’s indigenous innovation strategy.91

Existing programs such as the National Technology Industrial Base (NTIB) and numerous statutory authorisations allow the US Government to fill shortfalls in defence-related industrial capacity. An expansion of the membership and scope of the NTIB among US allies would nonetheless be of value in diversifying the industrial base of the United States and its allies and could form the basis of an allied free trade area in defence-related technology and materiel that could meet shortfalls due to emergencies or high demand.92 The recently announced Australian, United States and United Kingdom agreement to build a replacement nuclear submarine for the Royal Australian Navy is a good example of effective alliance cooperation on industry policy, at least in terms of strategic intent, although it remains to be seen how effectively this project is managed.

Towards an Australian geoeconomic policy agenda

The growing relevance of geoeconomic statecraft has important implications for Australian Government process and policy, as well as for the Australia-US alliance. However, as this report has demonstrated, there are costs and benefits associated with the use of geoeconomic statecraft, as well as major questions around its effectiveness in promoting geopolitical objectives. Analysts have historically underestimated the prospects for US power and influence based on geoeconomic thinking. Interrogating the analytical errors of the past should be an important element of geoeconomic policy development. However, there are also grounds for questioning whether the current US administration is well placed to effectively implement a geoeconomic agenda given domestic political constraints.

The G7 and the Quad may be the best forums through which to address China’s economic coercion since it is only the collective economic weight of the United States, the European Union and Japan that is likely to threaten China with substantial economic costs. Australia’s previous efforts to elevate the G20 as a forum for global cooperation were arguably misdirected given the lack of common interests and values among that forum’s membership.93

International law already provides an umbrella under which collective responses to Chinese economic coercion can be organised, including retaliatory measures. UN General Assembly resolutions provide that “no State may resort to or encourage unilateral recourse to economic, political or other measures to compel another State to subordinate to it the exercise of its sovereign rights.” Article 49 of the Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts maintains that states may implement countermeasures in the case of a violation of international law.94 These authorities can be invoked in parallel with WTO dispute resolution mechanisms and may serve as the legal basis for the emerging EU countercoercion framework.

To recapitulate some of the recommendations already made earlier in this report:

- Australia and the United States should aim to capitalise on the concerns China’s use of geoeconomic statecraft raises for countries in the Indo-Pacific region. Recent joint bilateral communiques with Australia’s regional and extra-regional partners have identified economic coercion as an issue of joint concern, implicitly raising the threat of a collective response.95

- A major priority for Australian policymakers should be to engage the United States with the WTO reform process and encourage the United States to invest in the international and regional trade promotion and trade defence architecture. Trade expansion and diversification among allies will better promote economic resilience than trade restrictions aimed at China.

- An expansion of the membership and scope of the NTIB among US allies would be of value in diversifying the industrial base of the United States and its allies and could form the basis of an allied free trade area in defence-related technology and material that could meet shortfalls due to security contingencies or high demand. The new AUKUS trilateral security partnership is a major step in this direction, although with major questions around implementation.

- In competing with China for geopolitical influence via foreign aid and official development assistance, Australia and the United States should focus on institution building. US and Australian influence within MDBs and the G20 Infrastructure Hub should also be better harnessed to counter China’s ODA and BRI. Multilateral development banks could as much as triple their lending capacity to address regional infrastructure gaps by reforming their prudential and liquidity standards.

Zack Cooper and his co-authors have proposed a number of joint Australian and US initiatives, including an expansion of AUSMIN to take in economic policymakers, the establishment of a working group on geoeconomic cooperation, the development of an attribution mechanism to identify economic coercion, a counter coercion fund and the development of a supply chain management agenda.96 These proposals are an important litmus test for alliance cooperation.