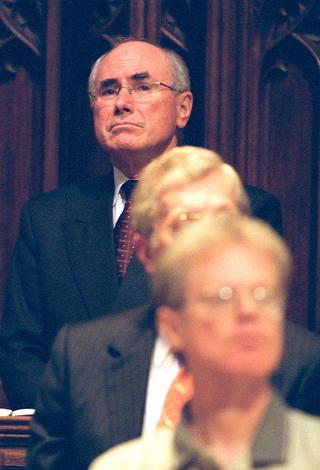

Australian Prime Minister John Howard arrived in the United States on 8 September 2001 on an official working visit to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the ANZUS Treaty. From a Washington DC hotel only a few blocks from the White House, he witnessed America suffer an extraordinary attack on September 11. This epochal event would transform global geopolitics and, in doing so, strengthen the Alliance between the United States and Australia.

In 2000, the relationship between Australia and the United States was rebuilding, in part due to the alignment of two conservative governments, the first term of the George W Bush administration and the fifth year of John Howard’s Coalition government. The 50th anniversary of the signing of the ANZUS Treaty in 2001 would be a celebration, with Howard to address a joint sitting of Congress, as well as an opportunity for him to meet the new president.

Bush and Howard spent four hours together on 10 September, attending an ANZUS commemoration ceremony and a 19-gun salute at a naval dockyard in Washington, which included America handing over the bell from the USS Canberra as a gesture of friendship. The USS Canberra was the only American ship ever commissioned in honour of an ally’s fallen vessel, at the request of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the Second World War, after he was told of exceptional action in battle by the Australian Navy steaming alongside American vessels at Guadalcanal. HMAS Canberra was struck by two Japanese torpedoes and was lost, along with 193 personnel.1

Prime Minister Howard later recalled discussing at the formal meeting at the White House on 10 September strengthening the Alliance, a potential free trade agreement and ‘just about everything except terrorism.’2 Howard believed the Alliance needed attention after losing some of its significance since the Cold War and due to New Zealand’s inactivity.

An informal barbeque attended by a high-powered audience including Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of State Colin Powell and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld showed the American bona fides for the Alliance.

On the morning of 11 September 2001, Howard took his early morning walk and spoke to Australian Treasurer Peter Costello about the unfolding failure of the Ansett Australia airline, before preparing for the day with his press secretary, Tony O’Leary. The press secretary mentioned as an aside a plane had hit New York’s World Trade Center; they both assumed it to be a light aircraft. O’Leary returned a few minutes later to say another jet had hit the second tower; they both realised it wasn’t an accident.

Sirens wailed in the background after a third plane, Flight 77, crashed into the Pentagon. They pulled back the curtains of the Willard Hotel and saw smoke rising. ‘We knew then, beyond any argument, that this was a concerted terrorist attack on the United States,’ Howard said.3

The deadliest terrorist attack on American soil was unfolding. A series of airline hijackings and suicide attacks by 19 militants associated with the Islamic extremist group al-Qaeda brought destruction, chaos and death to New York City, Washington DC and Pennsylvania. Up to 2,750 people were killed in New York, 184 at the Pentagon and 40 in Pennsylvania, where another hijacked plane crashed into the ground after passengers attacked the hijackers. Ten Australians died in the attacks.

The 9/11 attacks were not just more deadly than the attack on Pearl Harbor 60 years earlier, the attacks struck civilians in the very centres of American power and prestige, New York and Washington DC. Symbols of American life such as commercial airliners, the twin towers of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon became weapons or were destroyed on live television. 9/11 was thus widely understood as a broader assault on the American way of life and on liberal values and democratic institutions shared by many of America’s allies, including Australia.

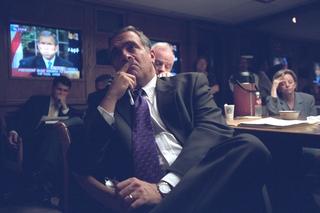

Howard was rushed across Washington to the basement of the Australian Embassy, where he wrote a brief letter to President Bush, expressing his solidarity and grief. He began a scheduled news conference at the Australian Embassy that afternoon by reading that letter.4

Dear Mr President. The Australian Government and people share the sense of horror experienced by your nation at today’s catastrophic events and the appalling loss of life. I feel the tragedy even more keenly being here in Washington at the moment. In the face of an attack of this magnitude, words are always inadequate in conveying sympathy and support. You can however be assured of Australia’s resolute solidarity with the American people at this most tragic time. My personal thoughts and prayers are very much with those left bereaved by these despicable attacks upon the American people and the American nation.Letter to President George W Bush by Prime Minister John Howard, 11 September 2001

The following day, Howard visited a sombre US Congress, where US Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert acknowledged ‘on behalf of the House, his appreciation for the solidarity of the Australian people and the presence of the Prime Minister today in this very difficult time.’6 Howard then attended a memorial service at the National Cathedral in Washington before calling the Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan to discuss the potential ramifications of the attack on the global economy.

Howard later recalled being in Washington and seeing America so ‘shocked and bewildered’ had a powerful effect on him. It may have hastened his decision to commit support to the United States.7 In turn, Howard’s decision would open a new chapter of the Alliance with Australia’s participation with the United States in the War on Terror, which undoubtedly became the dominant element of Australian security and foreign policy for the next two decades.

Howard was granted an exemption to fly on US Air Force Two from Andrews Air Force Base to Hawaii because all air traffic was grounded. Before he left the United States, he said at a press conference, ‘In many respects yesterday marked the end of an era of a degree of innocence following the end of the Cold War and a decade in which it seemed as though things which posed a continuous threat were put behind us.’

On that flight, after discussion with his foreign minister, Alexander Downer, Howard decided Australia would invoke the ANZUS Treaty, for the first time, in a move that had its own symbolism, being done during the week celebrating its 50th anniversary. The prime minister also correctly presumed the Australian public and the Labor opposition, led by Kim Beazley, would be supportive.8

A long-held expectation was if ANZUS was ever to be invoked, it would be for the United States coming to Australia’s assistance, not vice versa. The subtext of the genesis of ANZUS was a fear of a communist threat cascading through Asia to Australia; in this instance, a non-state actor attacked the United States. Clearly, this episode shows the Treaty was sufficiently broad to encompass a very different contingency than those contemplated in its founding. Further, it was clear the Alliance enjoyed deep support in Australia, with Howard’s invocation of ANZUS – in circumstances vastly different from what anyone might have imagined – garnering broad acceptance and endorsement. While the circumstances were unspeakably tragic, 9/11 revealed the Alliance to be strong and nimbler than presumed.

Before 9/11

Before 9/11, the Alliance needed attention. The advances Australia made with the United States in building and increasing the relevance of regional cooperation through initiatives such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) had been blunted by the reality of Asia in the 1990s and the differing priorities of successive Australian governments.

After the Alliance-friendly Hawke government of 1983-91, Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating moved concertedly towards Asia. To be sure, Australia joined the US-led coalition against Iraq after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1991. This was less out of any loyalty or obligation arising from the Alliance, but – at least publicly – because the coalition was a UN-mandated operation against a breach of the UN Charter and the fundamental principles of a rules-based international order.

The first Howard government (elected in 1996) had an uneven relationship with Asia, in part due to Australia’s exclusion from the Asian-European Summit meetings despite its work building APEC and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF).9 Notwithstanding his predecessor’s rhetoric that Australia was very much ‘in’ Asia, Howard’s experience was it was not ‘of’ Asia. The Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, along with Japan’s stagnation, also suggested promises of an Asian economic miracle might not materialise.

Looking towards the United States, Prime Minister Howard offered to expand US military exercises in Australia although his government’s first Foreign Policy white paper, In the National Interest, in 1997 didn’t prioritise the Alliance above three equally important key relationships for Australia, with China, Indonesia and Japan.10

Some historians argue the Alliance cooled during this era due to the differing styles and world views of Howard and President Bill Clinton.11 Clinton’s unwillingness to contribute US ground troops to the multinational force stabilising East Timor generated some tension. Howard later noted more was made of friction in his relationship with Clinton than actually existed: ‘I wasn’t as close to him as I became to George Bush…we ended up being close but not as close as I became to Bush.’12 And the Clinton administration provided logistical support and did some heavy diplomatic work lobbying the Indonesian Government to ease the transition to East Timorese independence.13

In late 2000, Australia’s Department of Defence released its Defence 2000: Our Future Defence Force white paper, which affirmed ‘Australia’s undertakings in the ANZUS Treaty to support the United States are as important as the US undertakings to support Australia.’14

So by September 2001, the atmosphere was ripe to revitalise the relationship. Australian governments are keen to have relations with new US administrations begin positively, ideally with a face-to-face meeting between the two leaders. This was especially the case with the new George W Bush administration, which, even before 9/11, was signalling a more assertive US foreign policy and, guided by experienced advisers including Vice President Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, a willingness to act unilaterally, if required, due to the United States’ status as the world’s lone superpower.

The United States would require allies.

Nevertheless, September 11 was a brutal shock that accelerated a turning point in the dynamics of the US-Australia relationship and in Howard’s governing, which was previously known for economic rather than foreign affairs policy concerns.

President George W Bush

President of the United States (2001-09)

On the morning of September 11, 2001, terrorists took the lives of nearly 3,000 people – including 10 Australians – in the worst attack on America since Pearl Harbor. As President, I became determined to keep the United States safe from terror.

Whether by coincidence or providence, Australian Prime Minister John Howard was in Washington, DC, on that terrible day. Without hesitation, he offered Australian assistance. In doing so, Prime Minister Howard invoked the ANZUS Treaty for the first time.

Prime Minister Howard was true to his word. Australia was by our side as we fought in Afghanistan and Iraq. I am forever grateful to have had the support of our unwavering ally.

As we celebrate the 70th anniversary of this remarkable Alliance, it is clear the United States and Australia must always stand together to ensure the security and prosperity of future generations. Laura joins me in sending best wishes. May God bless you.

Invoking ANZUS

When offering condolences to the American people on behalf of Australia during a Parliamentary sitting on 14 September, Prime Minister Howard said ‘The Government has decided, in consultation with the United States, that Article IV of the ANZUS Treaty applies to the terrorist attacks on the United States. The decision is based on our belief that the attacks have been initiated and coordinated from outside the United States. This action has been taken to underline the gravity of the situation and to demonstrate our steadfast commitment to work with the United States in combating international terrorism.’15

Australia was first but not alone in activating a treaty; on 4 October, the 19 member states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)16 invoked Article 5 of the Washington Treaty, which states an armed attack on one or more of the allies in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all.

Into Afghanistan

Following Australia’s indication of support, the Australian Defence Force liaised with the United States Central Command (the US military headquarters responsible for coordinating US military action in the Middle East as well as parts of South and Central Asia) about potential commitment to ‘Operation Enduring Freedom’ against Taliban forces in Afghanistan. Just over a month after the terror attacks on the United States, Prime Minister Howard announced on 17 October Australia’s military contribution to the ‘International Coalition Against Terrorism’ would include: two P-C3 Orion long-range maritime aircraft for maritime patrol and reconnaissance; a 150-man SAS squadron; two Boeing 707 tanker aircraft, for air refuelling operations; a naval task group, comprising one amphibious command ship and frigate as an escort; four F/A-18 strike aircraft; and one frigate. Twenty-six other countries also contributed forces.

The initial Special Forces deployment commenced on 22 October, farewelled from Perth by the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition, Kim Beazley. Three days later in a speech in Melbourne, Prime Minister Howard said 9/11 was not simply an attack on America. ‘We were all the targets,’ he said. ‘Remember that Australians were among those who died so tragically. In a very direct way, September 11 was an attack on the rights of Australians, especially young Australians, to go about their daily lives and to move around the world with ease and freedom and without fear. If we left this contest only to America, we would be leaving it to them to defend our rights and those of all the other people of the world who have a commitment to freedom and liberty. We will not do it. We admire their strength and greatness, but Australians have always been a people prepared to fight our own fights. To do anything less on this occasion would be both strategically inept and morally indefensible, especially given the strength of our mutual commitment with the United States under the ANZUS Pact.’17

The Special Force Task Group commenced combat operations, dubbed Operation Slipper, in Afghanistan alongside US and coalition counterparts in early December to dismantle al-Qaeda.

The first non-US military fatality in Afghanistan was an Australian, SAS Sergeant Andrew Russell, killed by an anti-vehicle land mine on 16 February 2002.18 He was the first Australian military death in action since the Vietnam War more than 30 years prior. Sergeant Russell enlisted into the Australian Regular Army in 1986 and during his service in the Australian Defence Force was awarded the Australian Active Service Medal with East Timor clasp and International Coalition Against Terrorism Clasp, the Afghanistan Campaign Medal, the International Forces East Timor Medal, the Australian Service Medal with Iraq clasp, the Australian Defence Medal, the United Nations Medal with the United Nations Transitional Authority East Timor Ribbon, the Infantry Combat Badge and the Returned from Active Service Badge. He was deployed in Iraq in 1997, Kuwait in 1998 and East Timor (1999-2002) before his final deployment.

Australia’s special forces withdrew in 2002 after quick successes, including the capture of Kandahar International Airport in December. But the following year, the Taliban’s insurgency required a renewed commitment by Australia.

Phase two commenced in 2005. Australia redeployed a Special Operations Task Group drawn from the Special Air Services Regiment, the 4th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment, the Incident Response Regiment and logistic support personnel.19 That same year, Australia opened its first embassy in Kabul.

In phase three in 2006, Australia withdrew the Special Forces Task Group and sent the first of four reconstruction task forces to support Dutch-led reconstruction operations in the southern province of Uruzgan.

Australian forces remained in Uruzgan until late 2013, first as junior partner to the Dutch, then to the United States, and finally as the lead nation. As the Afghan predicament changed, so too did Australia’s objectives. Initially, of course, it was supporting the Alliance to fight terrorism and deny extremists a haven in Afghanistan. That changed to a more holistic objective to rebuild and establish a secure and democratic Afghanistan. From 2008-13, Australians trained the Afghan National Army 4th Brigade in Uruzgan.

Unfortunately, the conflict did not abate. A number of Australians died in 2011-12, including two on what Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston described as ‘a very bad day’ in May 2011;20 one in an Australian Army Chinook helicopter crash, and another who was shot by an Afghan National Army soldier with whom he was serving on guard duty. Another Afghan ally turned his weapon on Australians in October, killing three and injuring seven, and in August 2012, five soldiers died in two separate incidents, Australia’s worst day in combat since the Vietnam War.21

At the peak of operations, almost 3,000 Australian Defence Force personnel and Defence civilians were assigned to the operation at any one time. In the period to 2014, more than 26,000 Australian Army personnel served in Afghanistan.[^22] It came at a cost; 41 Australians lost their lives, more than 260 were wounded.

The Honourable John Howard OM AC

Prime Minister of Australia (1996-2007)

As is well known, I was in Washington on 11 September 2001 having the day before met President Bush in person for the first time. We had spoken by telephone on a number of previous occasions.The highlight of that visit was meant to have been an address by me to a joint sitting of Congress to mark the 50th anniversary of the signing of the ANZUS Treaty.

I had no way of knowing when I arrived in Washington of what was in store on 11 September. Naturally, the address to Congress could not go ahead. As a personal gesture of support and friendship to the United States, my wife and I sat in the gallery at the commencement of a specially convened joint sitting of Congress to respond to the attacks of the previous day. We were the only visitors there and were quite moved to receive a standing ovation. I later went onto the floor of the Senate chamber, particularly seeking out Senators Hillary Clinton and Chuck Schumer, both of whom represented New York where some 2,750 people had died during the World Trade Center attack.

I knew the United States would respond to what had been the greatest violation of American sovereignty in that nation’s history. I also felt, instinctively, that Australia should offer assistance to our close ally. On 12 September, during a news conference at the residence of the Australian Ambassador, I said, ‘Australia will provide all support that might be requested of us by the United States in relation to any action that might be taken…’ Furthermore, I said in answer to a question, ‘I’m talking diplomatically and otherwise. We haven’t been requested to provide any military assistance but obviously, if we were asked to help, we would. It is very important at a time like this that America knows that she’s got friends.’

In answer to a specific question about military support, I replied, ‘Well we haven’t been asked to. What I’m saying, Alison, is that we would provide support within our capability.’ During the news conference I characterised my view of the circumstances with these words, ‘…we have to accept that this is an occasion where we should stand shoulder to shoulder with the Americans because this is not just an assault on America, it’s an assault on the way of life that we hold dear in common.’

I made these commitments without prior consultation with Cabinet as I knew that in saying what I did I would have the full support of my colleagues. Indeed, my words echoed the sentiments of most Australians at that time.

In my news conference, I sought to give historical context to what had occurred the day before. I said, ‘In many respects yesterday marked the end of an era of a degree of innocence following the end of the Cold War and a decade in which it seemed as though things which posed a continuous threat were behind us. But regrettably, we now face a possibility of a period in which the threat of terrorism will be with us in the way the threat of a nuclear war was around for so long before the end of the Cold War. I think it is as bad as that and I don’t think any of us should pretend otherwise.’

Shortly after that news conference my wife and I and our travelling party left Andrews Air Force Base for Hawaii on our way home. The US Government had grounded all flights in and out of their country. An exception was made for my flight, which was on Air Force Two. During that flight, I had a lengthy discussion with the Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer. During that discussion, Alexander suggested Australia should invoke the provisions of the ANZUS Treaty. The provisions he had in mind were Articles IV and V.

Article IV stated that ‘Each Party recognises that an armed attack in the Pacific area on any of the Parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.’

Article V provided, inter alia, that for the purpose of Article IV an armed attack on any of the Parties was deemed to include an armed attack on the metropolitan territory of any of the Parties. Clearly, there had been an armed attack on the metropolitan territory of the United States.

Although invoking the Treaty was not an essential prerequisite to our offering military assistance to the United States, it struck both of us as a powerful way of demonstrating our depth of feeling as a nation on this issue.

Tom Schieffer, the US Ambassador to Australia, was travelling back with us on Air Force Two. I remember informing him of my and the Foreign Minister’s intentions regarding the ANZUS Treaty. He readily understood the significance of what I had told him. It would be the first occasion in the Treaty’s existence that it had been formally invoked.

A meeting of Cabinet had been convened for the early afternoon of Friday 14 September. At that meeting, I briefed the Cabinet on my visit to Washington. Cabinet fully endorsed the commitment I had made on 12 September and agreed the ANZUS Treaty should be invoked. Immediately after that meeting, I announced the government’s decision at a news conference.

Into Iraq

While the initial focus after 9/11 was Afghanistan, it was not believed to be the only haven for extremists associated with al-Qaeda, nor the Bush administration’s only focus in the Middle East. President Bush’s fiery State of the Union address opened 2002 by highlighting the regimes of Iran, Iraq and North Korea, for varying reasons. ‘States like these and their terrorist allies constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world,’ he said.23

As the known web of extremists spread, within the ‘axis of evil,’ Iraq was a lightning rod. It would become the most contentious battleground for the United States and its allies since Vietnam. The contrast with the US-led military coalition against Iraq, after its Kuwait invasion in 1991, would be stark. In 1991, almost all the Western democracies supported a UN-mandated operation not due to fealty or alliance obligations to the United States but because, as Prime Minister Paul Keating later wrote, ‘the overwhelming majority of us saw it as an absolutely necessary international response to an outrageous breach of the UN Charter and the most fundamental principles of a rule-based international order.’24

In the early 2000s, Prime Minister Howard led a subtle but important reframing of Australian security policy from the previously stout focus on the ‘defence of Australia’ to a broader mission, the ‘defence of Australian interests and values.’ This change was informed by Howard’s instinctive reaction to September 11 – and similar reactions in Australian and global public opinion that the 9/11 attacks were motivated less by animus towards the United States per se, and more by a hatred of pluralistic, largely secular and market-centred values and institutions. Any society organised along these lines could be the target of 9/11-style terrorist attacks. In this way, 9/11 reaffirmed and clarified the shared values that are core to the Alliance; while ANZUS was forged in contemplation of a state-on-state competition between communism and democracy, the nature of the 9/11 attacks – the motivation of the attackers, where and how they attacked, and the resultant horrific spectacle – gave the Alliance a new mission and rejuvenation of purpose, with the defence and security of liberal democratic values in the forefront.

The centrality of the Alliance to Australia’s foreign policy and strategy in the post-9/11 environment was confirmed in the DFAT policy white paper in February 2003, Advancing the National Interest, stating ‘Australia’s links with the United States are fundamental for our security and prosperity and that the strengthening of our alliance is a key policy aim.’25

Australia also saw threats within its own borders. The different nature of this ‘war,’ which required global intelligence cooperation and increased attention on homeland security, was apparent in 2002 after a number of Australians were arrested on terrorism charges.

The most prominent accused of al-Qaeda links, David Hicks, was transferred to the Camp X-Ray prison at Guantánamo Bay, where he was interviewed by Australian Government officials from ASIO, the Australian Federal Police and DFAT. Many other Australians were later prosecuted for terrorism acts, including threatening government officials, training with al-Qaeda and planning attacks on Australian soil. Threats to Australia’s security were no longer on disputed battlegrounds or oceans; they could emerge from a suburban street anywhere in the world, and the Alliance would be a key resource in combatting this new class of threat.

The War on Terror was a broad collaboration between many nations but Australia was an enthusiastic partner of the United States. As Prime Minister Howard told a joint session of Congress in June 2002 (after his proposed speech on 11 September 2001 was abandoned), ’My friends, let me say to you today that America has no better friend anywhere in the world than Australia.’26 And in July, Foreign Minister Downer gave a speech in Dallas ‘reaffirming Australia’s commitment to the dynamic and diverse relationship with the United States.’27

But Australia didn’t offer blind support. In August, Prime Minister Howard told President Bush a UN Resolution obliging Iraq’s Saddam Hussein to readmit weapons inspectors was essential for Australia to support any subsequent US push to topple Hussein.

Australia’s position was complicated by its own security concerns after evidence emerged from Afghanistan in early 2002 of plans by al-Qaeda affiliates in Southeast Asia to attack Western targets (including Australian) in Singapore.28 This followed Osama bin Laden explicitly mentioning Australia as a target in his first taped message after the September 11 attack.29

Australia’s dilemma was if the War on Terror was in Australia’s neighbourhood then joining a US-led campaign in Iraq might be a distraction. Moreover, international support for the US position on the Hussein regime was weaker than expected and Australian public opinion followed, with substantial opposition to Australia joining a military campaign to oust Hussein.30

Accordingly, Prime Minister Howard’s National Press Club address marking the first anniversary of the September 11 attacks supported the broad US approach to the War on Terror while also affirming Australia’s security priorities remained closer to home.31

Then terror hit Australians. On 12 October 2002, a series of bombs in Bali, Indonesia killed 202 people, including 88 Australians and seven Americans. It was apparent almost immediately, due to the venues chosen, the attacks were targeted at holidaying Australians. President Bush called Howard expressing deep sympathy and noting the war against terror must continue.32

Australia’s shock at the Bali bombings echoed America’s reaction to September 11. Fears that post-9/11 terrorism had global ambition and reach – extending beyond the United States and Europe to target Australians – became real. Terrorism directed against Australian civilians was now core to Canberra’s security policy concerns and the primary factor binding it closer to Washington.

Yet joining an American-led coalition moving into Iraq remained a contentious proposition for large swathes of the Australian public, especially without the United Nations sanctioning the plan. Mass protests against military intervention in Iraq followed shortly after the Bali attacks, in December and again in February 2003, with hundreds of thousands of people joining protests across Australia. The Sydney gathering was reported to be the largest protest march in Australian history.33

A week after the February 2003 protests, Prime Minister Howard travelled to the United States for talks with President Bush. At the Oval Office photo opportunity, a journalist asked the president ‘whether you count Australia as part of the “coalition of the willing”?’

President Bush responded ‘Yes, I do. You know, what that means is up to John to decide. But I certainly count him as somebody that understands that the world changed on September the 11th, 2001.’34

The debate on whether to join an invasion of Iraq – and to do so with or without UN support – produced profound partisan disagreement in Australia, with questions about the Alliance at its core. Labor insisted Australian involvement in an Iraq invasion be predicated on a UN mandate; otherwise, Opposition Leader Simon Crean charged, the government was committing Australian forces ‘solely on the say-so of George W Bush.’35

Labor’s position was Australia could decline to join the US-led ‘coalition of the willing’ without undermining the Alliance. Labor figures such as Kim Beazley – with unimpeachable pro-Alliance credentials – described the Iraq commitment as ‘a profound mistake we should not have blundered into’ that would leave both Australia and the United States ‘extraordinarily vulnerable.’36

The episode is a rare instance of Australia’s major political parties openly disagreeing on an issue concerning the United States, with claims about commitment to the Alliance – or undue fealty to the United States – figuring prominently in the cut and thrust of the debate around the Iraq deployment. As US Ambassador Tom Schieffer noted at the time, the US Alliance typically sits above partisan politics (while at the same time, and in a rare intervention into Australian domestic politics by a US Ambassador, Schieffer accused Crean of appealing to ‘anti-Americanism’37). He implicitly conflated support, or opposition, of the Iraq invasion with support, or opposition, of the Alliance.38

Conflict about involvement in Iraq exposed broader questions about the Alliance, most particularly whether being an Alliance partner obliged, or even compelled, Australia to join the United States. And if an Australian government declined a US request to join, would the Alliance be robust enough to survive, let alone allow such questions to be posed without politicising the Alliance?

Events moved quickly. Prime Minister Howard pledged Australian support to the US military campaign, Operation Iraqi Freedom, on 18 March 2003, the day before President Bush formally asked Australia to be part of the US-led ‘coalition of the willing’ in military operations against Iraq.39 The president also told Saddam Hussein he and his sons had 48 hours to leave Iraq.

Two days later, on 20 March, Prime Minister Howard confirmed the Australian commitment of up to 2,000 Defence Force personnel to a US coalition to disarm Iraq of weapons of mass destruction. The commitment included Navy frigates, a Special Forces Task Group, a squadron of F/A-18 aircraft, and C-130 Hercules aircraft.

How the ‘coalition of the willing’ moved to this point remains an issue of recriminations and regret. The US contention that Iraq was concealing weapons of mass destruction and fomenting links with terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda relied on intelligence that was questioned by much of the global community, including key members of the UN Security Council. The UN Security Council did not support any military action against the Iraqi regime because weapons inspectors in the country had not reported anything worth prosecuting.

Ultimately, the countries willing to commit ground troops to the Iraq invasion without United Nations backing – the ‘coalition of the willing’ – were the United States, United Kingdom, Australia and Poland. The Howard government justified its participation with reference to UN Resolution 1441 from November 2002.40 It outlined breaches by Hussein’s Iraq since the 1991 Gulf War of a number of UN resolutions, most importantly the refusal to grant unrestricted access to UN weapons inspectors.

Australia contended Iraq remained in breach of the UN Resolution and had, or was in the process of obtaining, weapons of mass destruction. Support for Australia’s position came from the report of the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission’s Hans Blix to the UN Security Council in January 2003, which stated that ‘Iraq appears not to have come to a genuine acceptance – not even today – of the disarmament, which was demanded of it and which it needs to carry out to win the confidence of the world and to live in peace.’41

Hindsight shows there was undue haste in accepting that conclusion but, as Howard told the National Press Club in March of 2003, they couldn’t afford to ‘give the green light’ to the further proliferation of such weapons to regimes including North Korea.

‘If the Security Council fails the Iraqi test it will not pass the test of North Korea,’ Howard said. ‘These reasons for our direct and urgent commitment to the cause of disarming Iraq must be seen against the background of the different world in which we now all live.’ 42

Prime Minister Howard also noted in Parliament that month, ‘Our Alliance with the United States is unapologetically a factor in the decision that we have taken. The crucial, long-term value of the United States Alliance should always be a factor in any major national security decision taken by Australia.’43

Australian forces performed admirably in Iraq, took no casualties and, as Howard promised, were mostly quickly withdrawn after the fall of Baghdad. Australia flew humanitarian supplies into Baghdad afterwards.

Indeed, during 2003 and 2004, Australia denied US and UN requests to increase its contribution to the multinational force in Iraq before deploying a battlegroup in 2005 to provide security for Japanese engineers and help train Iraqi security forces.

By 2006, approximately 1,400 Australian soldiers remained with US and other coalition forces engaged in reconstruction and rehabilitation work in Iraq. Australia substantially reduced its forces after the election of the Rudd government in 2007; Australian combat troops ceased their operational role in Iraq on 31 July 2009 and by May 2011 all non-US coalition forces withdrew from Iraq.44 No Australian service personnel died in combat in Iraq although four died in accidents and one from injuries sustained in an improvised explosive device blast in 2004.

After Hussein’s regime fell, the Bush administration commissioned the Iraq Survey Group to determine whether any weapons of mass destruction existed in Iraq. After 18 months’ investigation, the team found ‘no credible indications that Baghdad resumed production of chemical munitions’ after destroying its cache in 1991. In October 2004, President Bush said the analysis ‘confirms the earlier conclusion of [UN Chief Weapons Inspector] David Kay that Iraq did not have the weapons that our intelligence believed were there.’45

Prime Minister Howard later said the intelligence information provided to justify invading Iraq was ‘not concocted’ but ‘factually inaccurate’ and American security agencies, in good faith, believed it.

‘This whole idea that the thing was invented and it was a lie is not right,’ Howard said in 2011. ‘There were factual errors. The conclusions were not supported by what was ultimately found. That’s true. I accept that. That’s self-evident. But this idea that right from the very beginning the whole thing was a lie is wrong.’46 In 2004, an Australian Parliamentary inquiry found ‘there was no interference in the work of the (Australian) intelligence agencies.’

“One of these things you should always remember about the Americans is that they are remarkably vulnerable sometimes when it comes to self-belief. They often overdo this feeling that nobody likes them. And they, therefore, reach out to people who have appeared to be consistent friends over the years. And that is part of the reason why the American Alliance is so strong; they know that there’s only really been one country that has stood beside them in every major conflict in which they’ve been involved since World War One and that’s Australia.”John Howard, Conversations with Richard Fidler, ABC Radio, 2011

The consequences of the September 11 attacks were profound and remain ongoing. They cemented a close personal and political alliance between Howard and Bush, who named the prime minister a ‘man of steel’ when presenting the Presidential Medal of Freedom to him at the White House in 2009. It is awarded at the discretion of the president for ‘especially meritorious contribution to (1) the security or national interests of the United States, or (2) world peace, or (3) cultural or other significant public or private endeavors.’

Australia emerged from the War on Terror with impeccable Alliance credentials. As an early, enthusiastic member of the ‘coalition of the willing’ in Iraq, Australia earned respect and influence in Washington and in allied foreign capitals, cementing its reputation as a steadfast and capable ally. Quite simply, being at the ‘pointy end of the spear, which means taking more risk earlier, resulted in Australia having more say,’ said Michael Green, former National Security Council Director for Asian Affairs.47

Earning Alliance merit did not come without cost. The Iraq conflict was deeply unpopular in Australia, generating the most partisan strain and scrutiny of the Alliance since the Vietnam conflict. But many argue this is not necessarily a bad thing. The War on Terror triggered a lively and ongoing debate about Australian national security and a frank assessment about Australian security priorities and defence capabilities, the long and costly Middle East conflicts dispelling any romanticism or sentimentality about the costs and benefits of the Alliance.48

These are the twin legacies of Australia’s long partnership with the United States through the post 9/11 conflict. Australia’s Alliance credentials are virtually second to none in Washington. This gives Australian policymakers and strategic thinkers considerable scope and confidence to pursue Australia’s national interests, to develop the necessary capabilities in coordination with the United States, and more broadly, to shape the Alliance to serve Australian priorities closer to home than the Middle East. As the Indo-Pacific emerged as the focus of geostrategic attention through the 2010s and beyond, these two legacies would see the Alliance assume even greater relevance and significance for Australia.

General David Petraeus AO

Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (2011-12), Commander of the International Security Force (2010-11), Commander of US Central Command (2008-10)

I think the world of Australia and its people, and I have a particularly special place in my heart for its soldiers, spies and diplomats.

I was privileged to develop my assessment of Aussies and Diggers from a unique set of vantage points. Most significantly, I was enormously privileged as an American soldier to command Australian forces in two wars, Iraq and Afghanistan. In fact, I may be the only American to enjoy that distinction in some 70 years.

Needless to say, those commands also entailed a good bit of interaction with various Australian prime ministers and foreign and defence ministers, as well as Aussie diplomats. Beyond that, following my time in uniform and while serving as Director of the CIA, I got to know – and came to respect highly as well – those leading and serving in Australia’s intelligence services.

After leaving government, I enjoyed the good fortune of getting to know Australia’s business community as a partner in the global investment firm KKR, among the largest investors of its type in Asia. Finally, I have also been fortunate over the years to have been actively engaged with numerous institutions in Australia, including the Lowy Institute, the Australian Defence College, the American Chamber of Commerce in Australia, the Australian War Memorial, and a number of other organisations.

I have thoroughly enjoyed and deeply appreciated my interactions with all those of the Land Down Under over the decades.

Those interactions have been particularly enjoyable and rewarding because of the qualities and attributes exhibited by those with whom I have been privileged to work. This is, in part, because Aussies invariably punch way above their weight class in every endeavour in which they engage. In fact, I have often identified Australia as ranking among America’s most highly valued allies, partners, and mates, demonstrating impressive professional competence, commitment and capability in their every undertaking.

I cannot adequately express how important it was to me over the years, for example, to be able to call on Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston or intelligence chief Nick Warner and their various comrades when we needed assistance on the battlefield or in the world of intelligence.

Nor can I express sufficient gratitude for Prime Minister Julia Gillard being the first head of government of the coalition countries in Afghanistan to support the extension of the mandate for the International Security Assistance Force. And the list goes on and should include Foreign Minister Julie Bishop for the exceptional insights she shared over the years, the Lowy Institute’s incomparable Michael Fullilove for innumerable opportunities to compare notes, and many other ministers, soldiers, scholars, diplomats and spies. Each of them exemplified what I found so impressive in virtually all Aussie leaders I have known, as well as in those they were privileged to lead.

In my experience, most Aussies are distinguished by a number of features that Americans find particularly appealing: a healthy bit of irreverence, an egalitarian spirit, fierce loyalty to mates, pragmatism, a delightful penchant for irony, a wonderful sense of humour (often self-deprecating), a rejection of self-importance, a degree of bluntness (albeit not as pronounced as that of my Dutch forbears), love of the great outdoors and sports, a general spirit of tolerance (except for those who succumb to self-importance), and open-mindedness. Aussies also have a wonderful appreciation for good food and wine (as well as beer, of course) and for seeking to make the best of difficult situations, with Australian soldiers as quick to observe during exceedingly tough moments as are American soldiers that, ‘It could always be worse.’

In sum, I have a ton of time for those from the country appropriately branded the Wonder Down Under and often also described as ‘the Lucky Country.’ Given its natural blessings, stable (albeit occasionally noisy) political system and general prosperity, lucky is, indeed, an accurate description of Australia. In turn, I count myself very lucky to have gotten to know Australia and many Australians – and to have served with Aussies in missions of consequence in tough places against determined adversaries. In fact, were I ever to find myself in a tough assignment again, I would very quickly seek Australian mates. There are none better.